Danespotting: Danish furniture design – still relevant?

As already stated our visit to Copenhagen and CORE 10 was without question one of our more disappointing trips.

Largely because of the complete lack of imagination, innovation or indeed quality that we found.

It’s certainly a phenomenon in all walks of life.

What do you mean?

Well, at one point, you’ve got it, then you lose it. And it’s gone forever.

All walks of life.

Georgie Best, for example, had it, lost it.

Or David Bowie or Danish design.

Danish design. Some of their modern stuff’s not bad.

No, it’s not bad, but it’s not great either, is it?

And in your heart you kind of know that although it looks all right…

It’s actually just…..

Even within the pantheon of Scandinavian design “Danish design” occupies an elevated almost mystic position.

Verner Panton, Arne Jacobsen, Finn Juhl, Poul Kjaerholm, Hans J. Wegner dot dot dot

It is probably fair to say that no country has given post-war design more “stars” than Denmark.

Especially when you calculate the “star designer to citizens” ratio.

However.

Too few Danish furniture producers understand why that is.

It’s not the ageometric shapes and the bright colours.

As with the likes of Egon Eiermann, the majority of those who embody “Danish design” were architects who in the years before the Second World war regularly created individual furniture pieces for their projects – but who played no real role in industrial furniture production.

The social and cultural changes of the 50s and 60s effectively created the mass market for contemporary furniture: and the furniture producers found in the leading architects of the day a ready source of innovative, experienced furniture design talent.

The designers however largely remained architects who produced occasional furniture designs on the basis of their architectural understanding and processes.

Arne Jacobsen’s Ant chair, for example, began life as a canteen chair for a factory Jacobsen was working on. Through contact with Fritz Hansen the project developed, largely driven by an interest in creating a product to compete with Charles and Ray Eames plywood furniture range.

Which brings us onto the second impulse: the innovation of the period.

The Eames DSR, for example, is not an especially stunning chair – however the moulded plastic seat was revolutionary at that time. Exactly as with Eames’ moulded plywood or Verner Panton’s plastic cantilever chair. Much of what we consider design classics today are such not because of their appearance, but because of their historical importance and the fact that when they were first released they re-defined genres and as such entered the collective psyche.

A related factor was the availability of materials per se. Traditionally furniture had been made of wood, the Bauhaus movement and modernism briefly introducing metal and glass into the vocabulary; until in the late 1940s a shortage of materials meant that European furniture producers were limited in what they could use. However in the 50s and 60s not only had the producers access to more materials, but industrialization was producing ever more new materials – and the furniture designers grasped at the new possibilities like frenzied children in free sweet shop.

Each new innovation being presented over new mass media such as television or colour printing and being eagerly snapped up by a European society thriving in the prosperity and security of the period.

All these factors combined to produce the concept of Danish design.

Or in other words Denmark found itself with the right people doing the right job in the right moment.

Today products for furniture companies are almost exclusively created by professional product designers, men and women whose job it is to produce products to order.

In itself no bad thing, assuming that the brief is motivated by the desire to achieve something new or improve an existing design.

Too much of what we saw wasn’t.

Too much of what we saw was simple mediocrity neatly wrapped in meaningless marketing twaddle to hide the fact the there was nothing new or interesting about the product.

As Renton would no doubt say: “Sooner or later this kind of thing was bound to happen.”

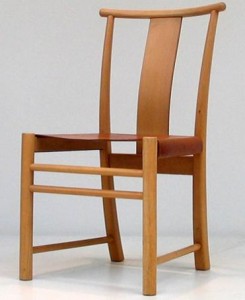

There is a poster on the smow office wall called “A Century of Danish Chairs”, it starts in 1905 and ends in 1979 – we experienced something similar at CODE 10.

It was genuinely as if the last 30 years hadn’t happened.

Danish furniture design hasn’t completely died, and even Sick Boy’s unifying theory of life isn’t completely valid; however, large sections of it have clearly lost their way and its hard to see where the impetus is going to come from to revitalise and revive Danish furniture design.

Not least when a tired affair such as CODE 10 is branded as demonstrating “…new approaches to design form, design thinking and the creative process”

Fortunately there were a couple of truly excellent items on display, and they will feature in our next Danespotting post.

Tagged with: Add new tag, ant chair, Arne Jacobsen, Bauhaus, Charles and Ray Eames, Egon Eiermann, Finn Juhl, fritz hansen, panton chair, Verner Panton