(smow) blog Design Calendar: November 7th 1929 – The New York Museum of Modern Art, MoMA, Opens

“The belief that New York needs a Museum of Modern Art scarcely requires apology. All over the world the rising tide of interest in the modern movement has found expression not only in private collections but also in the formation of great public galleries for the specific purpose of exhibiting permanent as well as temporary collections of modern art. That New York has no such gallery is an extraordinary anachronism. The municipal museums of Stockholm, Weimar, Düsseldorf, Essen, Mannheim, Lyons, Rotterdam, The Hague, San Francisco, Cleveland, Providence, Worcester, Massachusetts and a score of other lesser cities provide students, amateurs and the more casual public with more adequate permanent exhibits of modern art than do the institutions of our vast and conspicuously modern metropolis.”1

So announced the trustees of the future New York Museum of Modern Art their intentions in August 1929.

And just three months later on Thursday November 7th 1929 the Museum of Modern Art, MoMA, formally opened its inagural exhibition presenting 100 works by Cézanne, Gauguin, van Gogh and Seurat.

A quadruplet who indicate that at the institution’s opening the MoMA backers’ definition of “modern” had only little to do with the spirit of change sweeping 1920s Europe and more to do with the spirit of change that had swept Europe some 40 years earlier.

But then winds of change take a long time to blow across the Atlantic. At least from East to West.

But arrive it did. On January 18th 1930 the MoMA opened its third exhibition, Painting in Paris, a showcase of contemporary French painting that featured works by the likes of Pablo Picasso, Fernand Léger, Marc Chagall and the Paris based Catalan Joan Miró; and a showcase which proved so popular with the New York public it forced the MoMA trustees to begin, reluctantly, charging entry to the museum. The first two exhibitions and the majority of Painting in Paris had been free; however, two weeks before it was due to close the MoMA announced that on account of the unexpected popular success of the show they had received “innumerable complaints from visitors” who had “come intending to look at pictures and have instead been trampled, with no better compensation than a view of other visitors’ necks.””2

A fifty cent entry fee between 12 noon and 6 pm was considered the best solution.

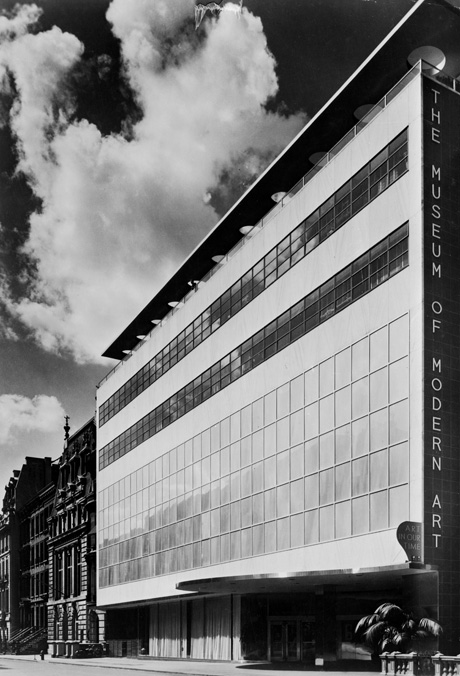

The original New York Museum of Modern Art, MoMA, home in the Heckscher Building, corner of Fifth Avenue and 57 Street.

Just as it didn’t take the MoMA long to discover European modernism it also didn’t take long for the MoMA to expand its horizon and to embrace modern film, music, architecture and design.

On February 10th 1932 the MoMA presented with Modern Architecture: International Exhibition its first architecture exhibition, quickly followed by Early Modern Architecture: Chicago 1870-1910 in January 1933 and in April of the same year a show looking at some of the more promising and notable young mid-western architects of the day. This passion for contemporary, modern architecture was unquestionably attributable to the hiring of Philip Johnson as the first Director of the institution’s Department of Architecture: and it was Johnson who also curated the New York Museum of Modern Art’s first dedicated design exhibition “Objects: 1900 and Today” which opened on April 5th 1933 and which, as the name implies, presented objects produced between 1900 and 1933. Some 100 in total. And which according to Paola Antonelli contained many objects from the curatorial team’s own homes, and even items from Philip Johnson’s mothers house.3 Which gives an indication of the level of personal interest the MoMA staff had in the subject. And the limited resources the fledgling museum had available.

This inaugural design exhibition was quickly followed by Machine Art in 1934, an exhibition arguably as important as Modern Architecture: International Exhibition and an exhibition which not only established the New York Museum of Modern Art as an important location for presenting, discussing and exploring contemporary design but also marks the establishment of the MoMA design collection.

Curated, somewhat inevitably, by Philip Johnson, Machine Art presented objects “produced by machines for domestic, commercial, industrial and scientific purposes”4 and demonstrated, according to the museum, “a victory in the long war between the craft and the machine.”5 No mean boast. And one they underscored with a display of some 400 objects including ball bearings, propellers, kitchen units, glass vases, copper tubing, steel springs and Poul Henningsen’s PH Lamp from Louis Poulsen, an object listed as retailing for the princely sum of $24.50.

Philip Johnson resigned from his post as Director of the Department of Architecture and Industrial Art shortly after Machine Art closed, being succeeded by first Ernestine. M. Fantl and then in 1937 by John McAndrew. And while under the tenure of these two directors the commitment to contemporary architecture remained unshakable, design, or “Industrial Art” as the MoMA insisted on referring to it, was limited to the occasional handicraft exhibition or as an occasional, additional, feature of an architecture and/or art exhibition; until that is 1938 when the MoMA presented first, Furniture and Architecture by Alvar Aalto, an exhibition in which Aalto’s moulded plywood furniture was given just as much, if not more, prominence than his architecture, before on September 28th 1938 the Museum of Modern Art began what would become their most influential and enduring contribution to American design, the Useful Objects exhibition series.

Premièred in 1938 with the exhibition “Useful Household Objects under $5.00”, the Useful Objects series, effectively, grew out of a conversation between Philip Johnson and the MoMA’s founding Director Alfred H. Barr in which they discussed their joint desire for an industrial design show “which would discriminate between “good modern design and modernistic cosmetics or bogus streamlining””6 A desire which in our books makes both men very sympathetic. Running nine years and formally ending with the 1947 showcase “100 Useful Objects of Fine Design (available under $100)” Useful Objects was ultimately about selling products, something it did very successfully, if the reports of the day are to be believed. Which we do.

Not that the MoMA was selling directly. The MoMA presented the objects in hands on, interactive exhibitions, and provided a list of retailers from whom visitors could purchase those products which interested them. And as such was, if you will, a forerunner of public consumer goods trade fairs. And provided many American consumers with their first contact with contemporary design, a contact which established the notion of “modern culture as modest, down-home, democratic housewares.”7 And thus arguably accelerated and anchored the popular acceptance of post-war American design, and so paved the way for the commercial success of designers such as Charles and Ray Eames, George Nelson or Alexander Girard.

Despite the clear commercial focus of the Useful Objects exhibition inclusion was based on a strict set of criteria; for example when compiling the inagural 1938 exhibition John McAndrew selected objects on the basis of their functionality, material and production processes.8 And this combination of usability and contemporariness was to define the Useful Objects shows under McAndrew’s successors; Eliot Noyes, who in 1939 was appointed the first Director of the newly created Department of Industrial Design, and subsequently Edgar Kaufmann Jr. the man who more than most was to establish the MoMA’s position at the vanguard of what would become known as Mid-century modernism.

A scion of the Philadelphia based Kaufmann department store dynasty, Edgar Kaufmann Jr first began cooperating with MoMA in 1938 as a consultant to the Useful Objects exhibition before in 1940 helping conceive the Organic Design in Home Furnishings competition. In 1946 Kaufmann took over from Eliot Noyes as Director of the Industrial Design department and one his first projects was the now legendary Competition for Low-Cost Furniture Design, a competition which of course ultimately gave us the Charles and Ray Eames plastic chair collection.

Edgar Kaufmann Jr was also responsible for transforming the Useful Objects exhibition series into the Good Design programme, an exhibition series which ran from 1950 – 1955. And which took the commercial connections initiated with Useful Objects to whole new levels. Organised in conjunction with the Merchandise Mart in Chicago – an immense shopping centre geared towards the wholesale and contract trade – the Good Design exhibition featured three showcases a year: in January and June in Chicago and then in winter in New York. The MoMA showcase presenting selected products from the two Chicago shows and thus being, in effect, a “Best of”. As well as of course a museum presentation of the Chicago “in-store” presentation. One could argue an affirmation.

However one must also add that as with Useful Design, and despite the clear commercial nature of the shows, inclusion to the Good Design exhibitions was via a selection process. They were curated shows in a museal sense. Ahead of each Chicago exhibition Kaufmann and two external judges selected exhibits from new products launched in the previous six months and according to strictly defined criteria. Yes Kaufmann unquestionably viewed objects as one with experience in retail, and yes one must query, for example, the predominance of furniture by Herman Miller and Knoll Associates in the Good Design exhibitions; however, as a devotee of Frank Lloyd Wright and a man who busied himself with design and architecture theory, Edgar Kaufmann Jr also had a clear understanding of what contemporary design is, was and should do.

Nor were the MoMA were alone in mixing museal presentation with economic interests, of blurring the lines if you will between the curated and the commercial presentation. The Good Design concept was, for example, greatly influenced by the For Modern Living exhibition Alexander Girard had organised at the Detroit Institute of Arts in 1949, and throughout the 1950s similar shows were being staged in museums and cultural institutions across the USA.

However, and aside from the scale and regularity of the shows, what made the MoMA Good Design shows so important was that in addition to presenting objects and advising where they could be purchased, the Good Design shows also awarded prizes and allowed all selected objects to market themselves as having been in the exhibition. Not only the start of the branding of “Good Design” but also the start of the maxim “MoMA = Good Design”. An association that many producers, designers and retailers still happily and openly play with.

In 1956 Edgar Kaufmann Jr left the museum and was replaced by Arthur Drexler, who would guide the MoMA’s Architecture and Industrial Design department for the next 30 years.

Three decades through which, and as with the years under Fantl and McAndrew, although the reputation of the MoMA’s architecture exhibitions continued to grow, its design department began to wane, becoming an institution much more associated with reflecting on the past than the present and/or the future. In the early 1980s, for example, as the first seeds of postmodern design were being planted in Milan and the Neue deutsches Design movement was starting to break through in Germany, the MoMA presented retrospectives of Eileen Gray and Marcel Breuer. Both valid themes for a design museum. But not exactly cutting edge. Almost as if having caught up with European Modernism in the 1930s the MoMA felt obliged to remain there while the rest of the world moved on.

Although to be fair, and without wanting to sound jingoistic, the years from 1960 onwards were not golden ones in terms of American design, nor did the new design movements sweeping Europe necessarily reach America. And despite its unquestionable international view the New York Museum of Modern Art, rightly or wrongly, tended to focus on themes of interest to America and Americans.

What did however continue was the growth of the museum’s collection, with works by the likes of Enzo Mari, Verner Panton, Jasper Morrison or Maarten Van Severen being added over the decades. Yet these works were never presented in thematic, contemporary exhibitions; instead design became something presented as “Recent Acquisition” or “Design from the Museum Collection” exhibitions rather than in context of current developments, current thinking, current ideas. Modern design.

Of late that has changed with exhibitions such as Contemporary Design from the Netherlands in 1996, the 2008 show Design and the Elastic Mind or the current Design and Violence demonstrating that the MoMA is capable of presenting interesting exhibitions that do explore contemporary design thinking and issues.

However in context of design the MoMA remains largely a place of reflection, a location for grand retrospectives, and, ultimately, in the words of Wolf Von Eckardt the place “which introduced and nurtured” modern American design9

Which to be honest, is no bad claim.

And something for which we should all be thankful.

1.”Publicity for Organization of Museum”, Museum of Modern Art Press Release, New York, August 1929 Source: http://www.moma.org/docs/press_archives/1/releases/MOMA_1929-31_0001_1929-08.pdf Accessed 07.11.2014

2.”MOMA to charge admission during last 2 weeks of Painting in Paris because of unexpected crowds” Museum of Modern Art Press Release, New York, February 17, 1930 Source: http://www.moma.org/docs/press_archives/27/releases/MOMA_1929-31_0027_1930-02-17.pdf Accessed 07.11.2014

3.Paola Antonelli “Design: die Sammlung des Museum of Modern Art. Objects of design from the Museum of Modern Art” Prestel, München, 2003

4.”Exhibit of machine art opens” Museum of Modern Art Press Release, New York, March 3, 1934 Source: http://www.moma.org/docs/press_archives/164/releases/MOMA_1933-34_0031_1934-03-03.pdf Accessed 07.11.2014

5.”Machine Art” in The Bulletin of the Museum of Modern Art, Vol. 1, No. 3, November 1933

6.Mary A. Staniszewski, “The power of display: a history of exhibition installations at the Museum of Modern Art” MIT, Cambridge, Mass., 1998

7.ibid

8.Paola Antonelli “Design: die Sammlung des Museum of Modern Art. Objects of design from the Museum of Modern Art” Prestel, München, 2003

9.Wolf Von Eckardt, Forms That Follow Function, Time, Vol. 122 Issue 18, p89, 1983,

Tagged with: moma, New York, The New York Museum of Modern Art