On Friday February 23rd the Vitra Design Museum open their 2013 spring/summer exhibition, Louis Kahn - The Power of Architecture.

Organised in conjunction with the Netherlands Architecture Institute "The Power of Architecture" is the first major Louis Khan retrospective in over two decades and promises to present the most comprehensive study ever of one of modernism's more interesting and alluring sons.

Albeit a son of modernism we suspect many of you will never have heard of.

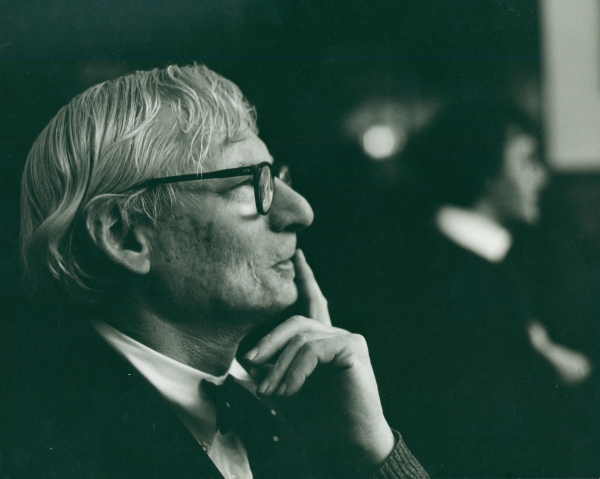

Born in Estonia in 1901, Louis Kahn was raised in Philadelphia. As the son of poor Jewish immigrants Kahn's early years are probably best described as "modest"; however, he was a gifted and diligent student and in 1920 won a scholarship to study architecture at the University of Philadelphia's School of Fine Arts. Following his graduation he embarked on a two year long "Grand Tour" of Europe; a tour that was to introduce him to both the emerging modernist movement as well as the wonders of historic European architectural traditions. Returning to America in 1930 Kahn struggled to find architectural work and turned to teaching and researching, first at Yale University and then the University of Pennsylvania, before in 1951 he was able to realise his first major project, a critically acclaimed extension at Yale University Art Gallery. It was to be a further decade before he could realise his first project outside the US, the Indian Institute of Management in Ahmedabad, a commission quickly followed by arguably his most important work: the National Assembly Building in Dhaka, Bangladesh. In 1974 Louis Kahn died of a heart attack in New York.

Although Louis Kahn could in many ways be considered a victim of the US depression of the 1930s - an era that saw him largely unemployed or at best underemployed - the time spent teaching and researching was to lay the foundations for his belated fame as it allowed him to fully develop his ideas on firstly architecture's social responsibility and secondly on the relationship between architecture and the natural world, both in terms of structural similarities and the connection between the inanimate building and the living environment.

And perhaps more importantly it allowed Kahn the freedom to combine the two in a vernacular modernism that confuses as much as it delights: the outwardly brutalist nature of many of Kahn's structure belying a much more classical approach to architecture that is often only apparent on the second, or third, look. His National Assembly Building in Dhaka for example looks like it wants to punch you hard between the eyes. Only when stop cowering do you realise it is nothing more menacing than a series of arches and columns.

Like some sort of abstract Gothic-Modern cathedral.

And indeed Kahn's portfolio is awash with structures and forms inspired by the Medieval, Gothic and Classical structures he witnessed on his numerous tours of Europe. Louis Kahn was fascinated by the monumental, be it medieval cities, classical bridges or religious house of all hues and whenever he visited Europe he would return with sketches and watercolours of those structures, or bits of structures, that spoke to him.

And when they spoke to him, it wasn't just in terms of their physical appearance.

In 1944 Kahn wrote, "No architect can rebuild a cathedral of another epoch embodying the desires, the aspirations, the love and hate of the people whose heritage it became. Therefore the images we have before us of monumental structures of the past cannot live again with the same intensity and meaning. Their faithful duplication is unreconcilable. But we dare not discard the lessons these buildings teach for they have the common characteristic of greatness upon which the buildings of our future must, in one sense or another, rely"

One of the lessons these buildings teach is that vertical, supporting structures needn't be constructed from solid stone, they can be hollow. Louis Kahn was to develop this lesson into one of his most important contributions to architectural theory; his distinction between "served" and "servant" spaces. For Louis Kahn "served" spaces are those spaces in a building that are actively used, "servant" spaces being those spaces that serve the utilised - principally staircases but also ventilation systems, liftshafts etc. Which may sound stunningly obvious, but until one starts to actively distinguish between the two and plan a building on the basis of such an active distinction one can't develop, for example, a truly modular system such as Fritz Haller's Mini/MidiMaxi. And before Louis Kahn, no one did actively define such a distinction.

Louis Kahn's relatively late entry into the higher echelons of practicing architects and the relatively limited number of projects he completed mean that while Kahn is widely acknowledged and respected in architecture circles; his name means next to nothing to most people.

Louis Kahn - The Power of Architecture is a wonderful opportunity to help rectify that.

Divided into seven sections the exhibition begins with a biographical introduction to the man and his work, before six themed sections explore his relationship with Philadelphia, his scientific research in the field of natural structures, the role of nature and classicism in his architecture and architectural thinking as well as the social and communal aspects of his structures.

We haven't seen the exhibition and so, as ever, can't comment on how well it achieves its aim of presenting a new perspective on Louis Kahn, his work and his contribution to architecture. We can however say that the exhibition premiered at the Netherlands Architecture Institute in Rotterdam and we've only read good things about it there. We expect the Vitra Design Museum have tweaked it a bit; we still expect only to read good things about it.

Louis Kahn - The Power of Architecture runs at the Vitra Design Museum, Charles Eames Str. 2, Weil am Rhein from February 23rd until August 11th 2013.

In addition to the exhibition itself the Vitra Design Museum is staging an extensive accompanying programme.

Full details can be found at www.design-museum.de