Whereas exhibitions featured in these pages are normally still in the first flush of youth, having recently enjoyed their vernissage and thus making their first public appearance, the presentation of Two German Architectures 1949-1989 at the Technische Universität Berlin is much more a finissage.

After a 13 year, 26 city, global tour, the exhibition has, in many regards, come home to retire.

Organised by the German cultural exchange organisation the Institut für Auslandsbeziehungen, IFA, in cooperation the Federation of German Architectural Archives, and including results from a research project undertaken by the Architecture Department at the Hochschule für bildende Künste Hamburg, Two German Architectures 1949-1989 does exactly what it say on the tin: presents post-War architecture realised in the former East Germany and former West Germany. And does so through a myriad of projects standing representative for thematic areas such as, University Education & Research, New Towns, Sport or Houses of Culture.

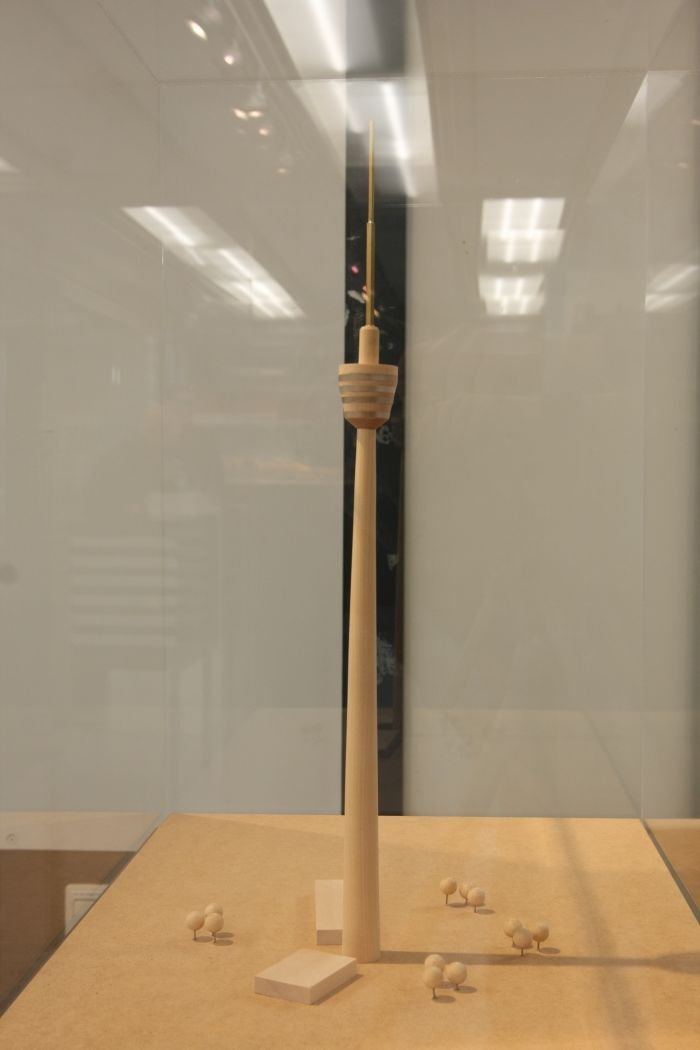

As an exhibition about post-war German architecture Two German Architectures, somewhat unsurprisingly, features projects by leading post-war German architects, including, and amongst many, many others Franz Ehrlich, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Hermann Henselmann, Hans Scharoun, Paul Schneider-Esleben, and Egon Eiermann, in addition to projects led by civil engineers including the Stuttgart Television Tower by Fritz Leonhardt, additions which neatly echo the message in the exhibition Visionäre und Alltagshelden. Ingenieure – Bauen – Zukunft at the Oskar von Miller Forum Munich, that without civil engineers most architectural visions would remain just that.

Although exploring the post-War architecture of the two Germanys Two German Architectures isn't however a direct comparison of the two architectures, but much more of the two social, two political, two cultural and two economic contexts in which the two architectures arose. And thus an indirect comparison of the two German architectures. The buildings exist for themselves. Uncommented. But open to interpretation, analysis and discussion.

In addition to being an exhibition about the architecture realised in the former East and West Germany, Two German Architectures is also an exhibition about the legacy of that architecture, and for all our contemporary relationship(s) to that architecture.

Whereas all conurbations have an ongoing discourse about architecture and urban planning, that discourse in Berlin is one largely guided by questions concerning our relationship(s) to the legacy of the architecture from the East/West years.

A state of affairs which makes Berlin a, when not the, most apposite of locations for the exhibition's adieu; not least on account of the DDR era architecture that is no longer to be found in the city.

The new reality post-Wall, and for all the new, new reality following the decision to make Berlin the German capital, means that Berlin has been subject to a lot of changes over the past two decades; or perhaps better put, the East Berlin cityscape has been subject to a lot of changes.

While demolition and reconstruction is a recurring, and invariably,controversial, theme in all cities, for example as recently discussed in context of the exhibition Stuttgart reißt sich ab at the city's Architekturgalerie am Weissenhof, the situation in Berlin is often less related to urban planning in terms of purely improving a space or purely in terms of responding to changing demographic demands, but as a (negative) reaction to the post-war history. To the post-war architecture.

While some buildings are vanishing from the Berlin skyline because structural failings mean they need to come down, in many cases it is much more the case that people simply don't like them, find them formally unattractive, and/or because they see in the building a representation of DDR ideology and transfer their dislike/hatred of the DDR onto the building, and/or because they want to reconstruct buildings demolished during the DDR years, and thus reconstruct the cityscape as it once was. Oblivious to the fact that if, as Lucius Burckhardt convincingly teaches us, landscapes don't exist, then cityscapes are even more imaginary, being but a hotchpotch of amalgamated memories and emotional connections. Not least because a cityscape is in constant change, cannot exist the way a brick or sandstone block does.

We've opined before in these pages that while there can be no arguments for saving every building by architect X or from epoch Y, there are excellent arguments for maintaining those buildings which are structurally sound and which can be adapted to their intended new function, arguments last made in context of the exhibition SOS Brutalism – Save the Concrete Monsters at the Deutsches Architekturmuseum Frankfurt.

In context of those buildings vanishing from the East Berlin skyline, and indeed elsewhere in the former DDR where buildings regularly vanish on account of the reasons noted above, one however not only removes the physical building, but also the necessity of considering them in context of both the wider German social, political and cultural history, and also of global architecture. They were, so the argument of the those pulling them down, simply Ost-Ruine - Eastern Ruins - that needed to be removed to make way for the new. Their removal therefore becomes in many regards self-explanatory and as buildings they become classed as unimportant, irrelevant. Which they may be. But may not. In which context we are greatly reminded of the words of Luise Mendelsohn in regard to Egon Eiermann's decision to demolish her husband’s Schocken department store in Stuttgart, "Later generations will be much better placed to asses Erich Mendelsohn’s importance in the development of 20th century architecture – and so we condemn that one of his few remaining works should be voluntarily executed by his countrymen"1

While condemning no-one, Two German Architectures provides a space for approaching such assessments of post-War German architecture, East and West, and the merits, or otherwise, of both the architects responsible and the works they realised; and thereby of the merits, or otherwise, of the works realised in East and West Berlin

And having started to consider such you can then stroll the short distance to Zoologischer Garten train station to consider the situation in the, so-called, and unironically so, "City West", before jumping in the S-Bahn to travel the short distance to the former East Berlin. Passing on your way that, arguably, most remarkable of post-War German architectural projects, the Hansaviertel estate with its results from the 1957 Interbau International Building Exhibition.

Featuring texts plans, photos and scale models, Two German Architectures is an exhibition which invites the visitor to approach and communicate with it at their own time and at the own level: you can buzz through it, read the short, comprehensible texts and thus become better acquainted with the themes, or take your time study the plans, photos, documents and use them as the basis for comparing, contrasting and entering into a dialogue with the works and that which they represent.

Devoid of dogma, or indeed opinion of any sort, Two German Architectures allows for a quiet, factual, but never dry, never dull (re)view of post-war architecture in Germany.

And arguably remains as relevant as it did when it premiered in Hamburg back in 2004. If not more so. Then the subject matter was fresher, the political discourse and posturing of the protagonists still young, raw, there was less space for considered opinion. In 2017 the discourse is maturer, more focussed, certainly better grounded, while the distance of time allows for an emotional distance that enables a more neutral view and thus a deeper, if you will, more honest, understanding and assessment of the works and their relationship to both their age and each other.

And potentially also a new won view on the architecture of not just East/West Berlin, but East/West Germany.

A bilingual German/English exhibition Two German Architectures 1949-1989 runs at the Technische Universität Berlin, Fakultätsforum im Architekturgebäude, Ernst-Reuter-Platz, Straße des 17. Juni 152, 10623 Berlin until Saturday January 6th.

Entry is free.

1http://www.spiegel.de/spiegel/print/d-42622632.html Accessed 29.11.2017

Full details can be found at www.ifa.de/two-german-architectures