Although Bauhaus did undeniably exist, sometimes we could all be forgiven for believing we had collectively imagined it. Not only on account of its ephemerality as an institution, but also because it existed in a period of history that is, generally, a little abstract, intangible, indecipherable for a majority of us. While today the popular image of Bauhaus is so ideal, represents such a utopia and eutopia, it has that tangible feeling of intangibility, of unreality, of something imaginary.

With the exhibition Bauhaus Imaginista the Haus der Kulturen der Welt in Berlin aim to allow for a more substantive understanding of Bauhaus.

Whereby one must start by saying that Bauhaus Imaginista at the Haus der Kulturen der Welt, HKW, Berlin is not just an exhibition; much more it is the culmination, summation and conclusion of a year of global research, symposia, discourse, and exhibitions. And an exhibition which not only brings the results of the year past together, but adds a final chapter of its own creation.

And thus completes, as much as one can, a project which in its attempt to approach a more substantive understanding of Bauhaus firstly distances itself from not only the Bauhaus institution(s), but for all from the popular narratives of the school(s), exploring the (hi)stories of Bauhaus in differing contexts, locations, cultures, and for all how Bauhaus is and was interpreted and understood outwith the contexts, locations, cultures in which it arose, how Bauhäusler responded outwith the controlled confines of Weimar and Dessau; before attempting to work its way back from such abstracted, dissipated and distanced positions to Bauhaus.

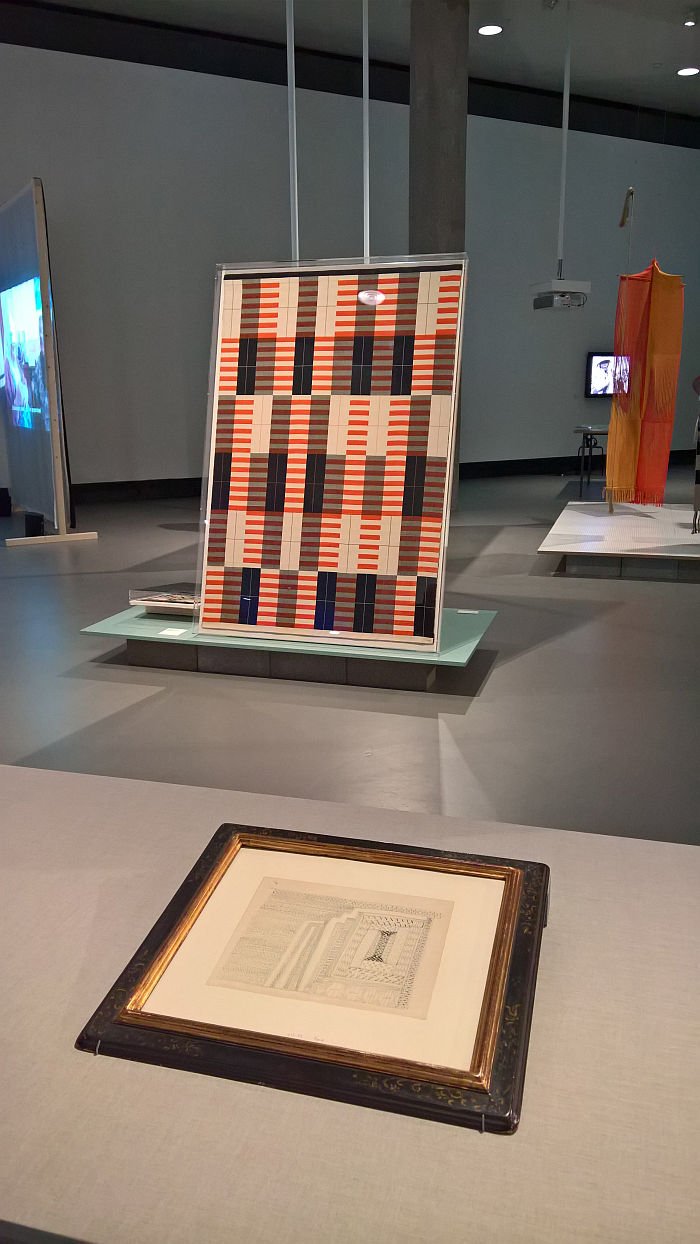

To this end Bauhaus Imaginista is constructed around four independent but complimentary chapters, each of which is visualised and introduced by a single object closely related to Bauhaus; an object which not only exists as a starting point for the subsequent exploration, but is also explanatory and indicative of and for the subject matter of the chapter and the associations the exhibition argues can be made back to Bauhaus.

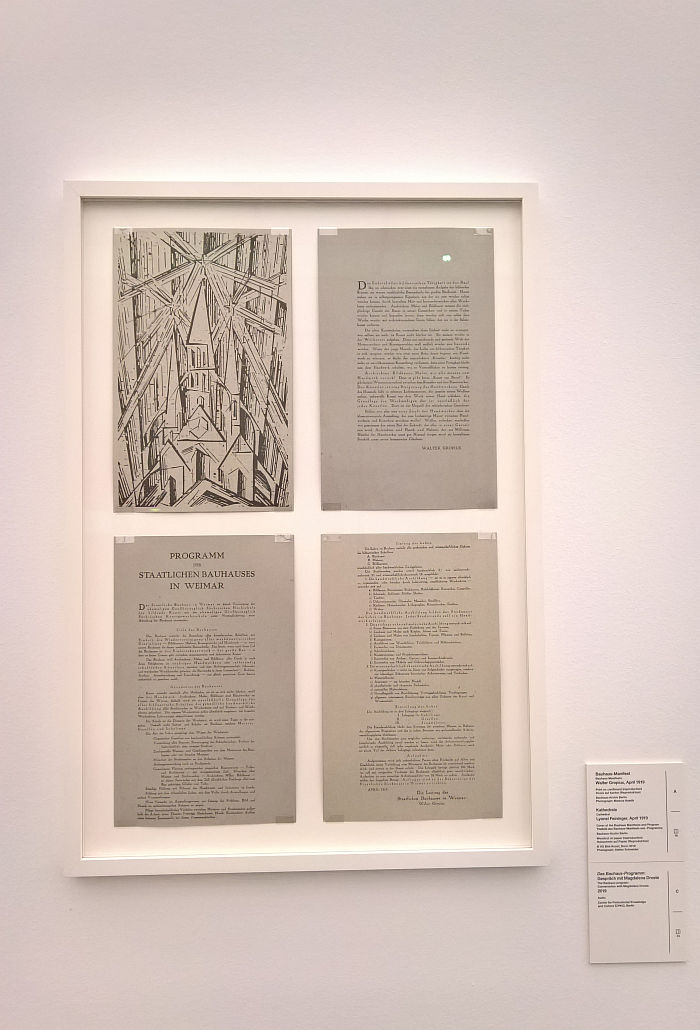

As an exhibition Bauhaus Imaginista has no natural starting point; however, the most logical place to begin is the chapter Corresponding With, represented as it is by Walter Gropius's 1919 Bauhaus Manifesto and his exhortation, "Architects, sculptors, painters, we must all return to craft! There is no "profession of art". There is no essential difference between the artist and the craftsman. The artist is an augmentation of the craftsman". And which is used as a starting point for an exploration of Bauhaus pedagogy in comparison with, and context of, two other inter-War reformist creative schools: Kala Bhavan established in 1919 in Shantiniketan, India, and Seikatsu Kōsei Kenkyūsho, established in 1931 in Tokyo, Japan. And a discussion that takes place through examples of student works, college publications and also the very real, personal, exchange that occurred between Bauhaus, Japan and India.

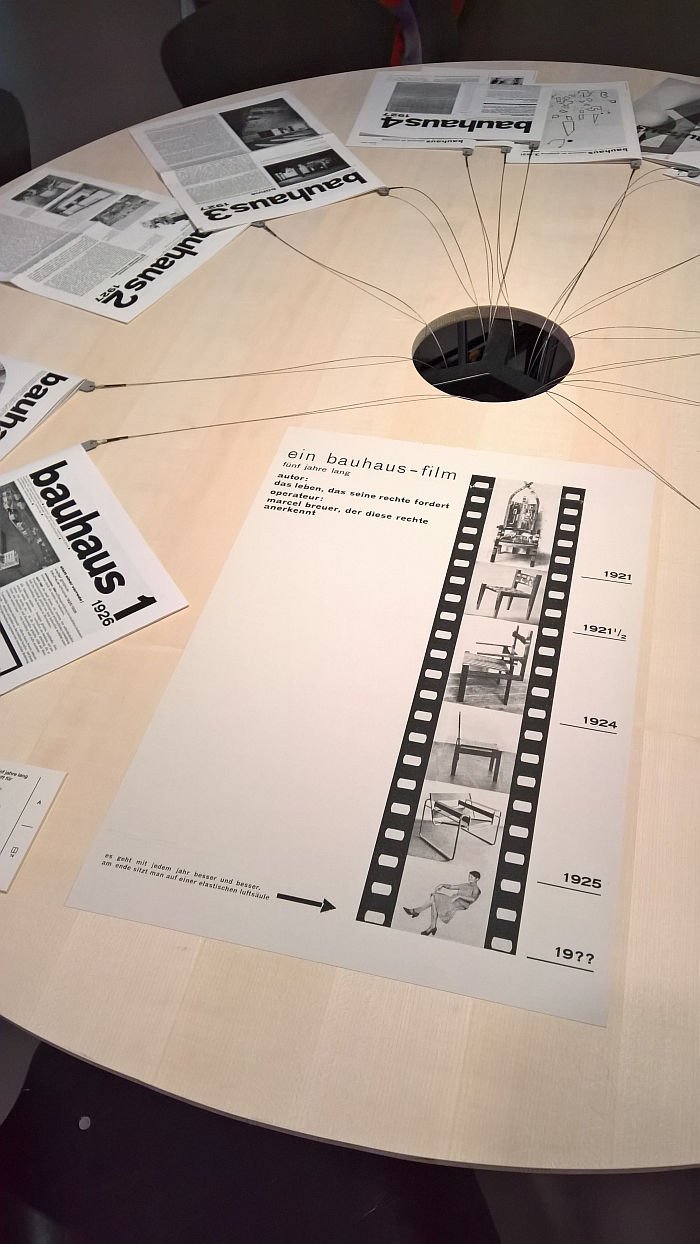

International exchanges which also feature in the chapter Moving Away, whereby the movement here is both figurative as well as geographic: the former underscored by the choice of Marcel Breuer's 1926 collage "ein bauhaus film. fünf jahre lang" as the chapter's visualisation. Published in the first Bauhaus magazine, Breuer's collage depicts the progression from his and Gunta Stölzl's 1921 "Africa Chair" in Weimar to his 1925 "Wassily Chair" in Dessau, and beyond. And thus in context of Breuer's designs is a formal, material, conceptual progression that took only 4 years, yet represents a span of eternity, a leap from a world that was already gone, to one that had not yet arrived, a leap, if you will, into the imaginary.

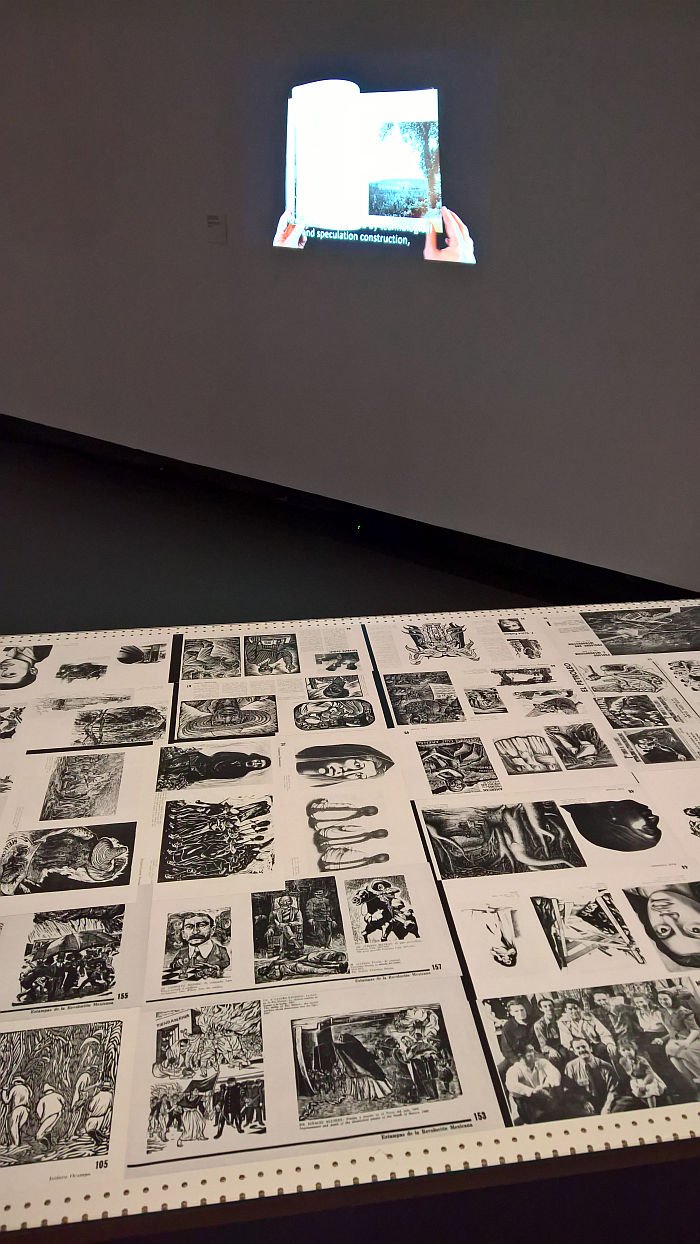

The more geographic exchanges being represented in Moving Away by considerations on projects with a (more or less direct) link to Bauhaus, in countries as diverse as China, India, Nigeria or Russia. And a geographic journey continued in the chapter Learning From, a chapter which starts from a 1927 sketch by Paul Klee of Maghrebian carpet patterns, and continues to explore what the curators refer to as the "premodern" Bauhaus, and how reflections on vernacular handcraft traditions influenced Bauhaus/Modernism and how that continued throughout the post-War decades as reflected by the likes of Marguerite Wildenhain's time at Pond Farm, California, Lina Bo Bardi in Brazil or the post-Independence (hi)story of the Ècole des Beaux Arts Casablanca.

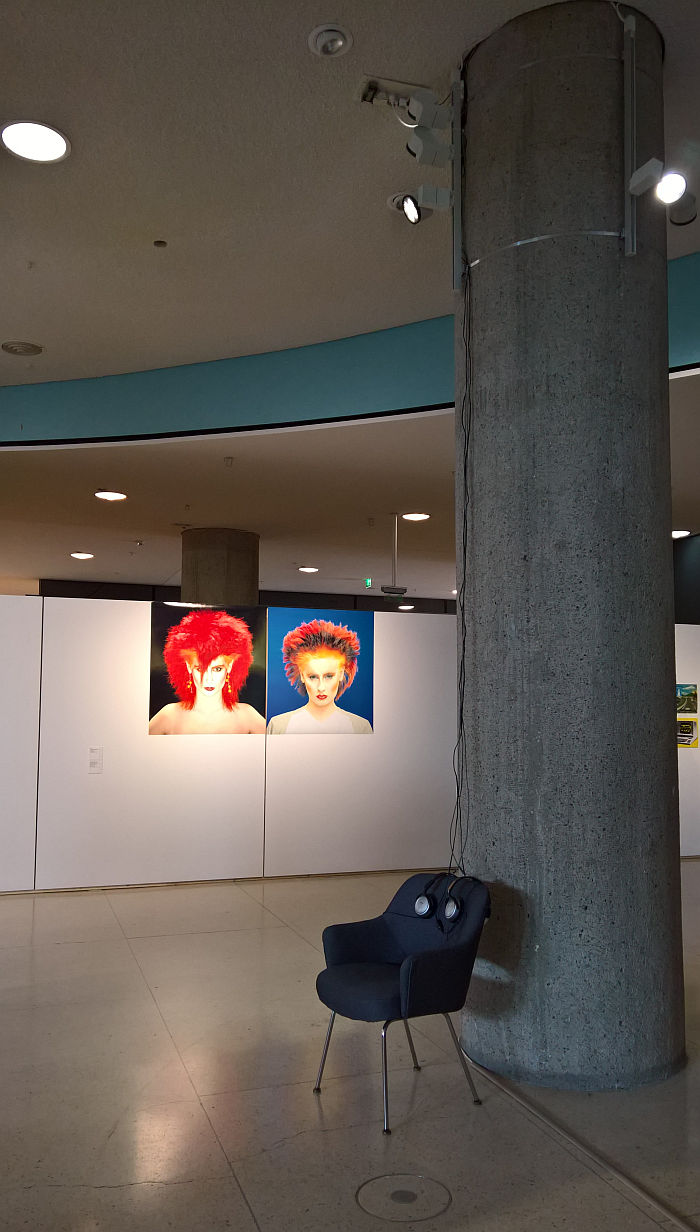

The "final" chapter, Still Undead, the HKW Berlin's contribution to Bauhaus Imaginista, explores experimentation with light and sound, at the Bauhaus and beyond, starting, radiating? from Kurt Schwerdtfeger's 1922 Reflektorische Farblichtspiele, a, well, reflective coloured light performance, and a presentation that in addition to all manner of contemporary and historic film and sound installations also includes reference to and discussion of, subjects as diverse as, the artist as engineer, the borders between art and advertising, and Vidal Sassoon's understanding of hair styling. No honest. And an understanding inspired, we learn, by a meeting with Mies van der Rohe. Which is without question the one thing we weren't expecting to learn from Bauhaus Imaginista.

And an imagination of Bauhaus that is going to keep us busy for a long, long time to come.

As a project, Bauhaus Imaginista exists as a very theoretical, conceptual, academic exploration of Bauhaus.

As an exhibition Bauhaus Imaginista is a much more accessible creature, if one that is just as involved, and one that is unapologetically programmatic as it carries historic considerations into the contemporary. For example, in the introduction to Still Undead, while reflecting on the "blurring of the borders between experimentation, institutionalization and commercialization" at Bauhaus the curators opine that "this tendency, to merge resistant experimental practices into consumption, emphasises the necessity for the re-politicization of art, technology and popular culture today", while in context of Corresponding With the curators argue that through the presentation, "it becomes possible to consider how institutions today, including schools of art and design, can imagine new ways of living that respond to patriarchal, xenophobic, and nationalist pressures". Yes. Whereby we'd note that (a) the vast majority of schools of art and design do. On our annual #campustour we experience just such week in week out, and across borders geographic and generic. The greater challenge is, surely, ensuring that they have the resources and freedom to allow them to, that the prevailing, and ever more self-confident, patriarchal, xenophobic and nationalist pressures don't impinge on their freedom.

Bauhaus of course being a notable example of just such. And thereby a (hi)story we can learn from. Including from (b) the ambivalence in the school's own response to such pressures.

The best known examples being, arguably, Herbert Bayer's numerous cooperations with the Nazis, but also Gropius and Mies van der Rohe completed commissions for the NSDAP, as did non-Bauhäusler Modernists such as Egon Eiermann, including cooperations long after a point had been reached when one could have had any doubts about the NSDAP's politics. And nor were such cooperations limited to right wing totalitarian regimes: former Bauhaus Director Hannes Meyer travelling to Moscow in 1930 with seven Bauhaus students to help build the Stalinist State, as did numerous progressive contemporaries, most notably members of the Neue Frankfurt project, including the likes of Ernst May, Hans Leistikow, Mart Stam or Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky. And again, that after a point when most doubts as to Stalin's political convictions should have been dispelled.

Imagining new ways of living is important, how those new ways are enacted, by whom and with what intentions, is more important; if we accept that architecture and design exist inextricably linked with cultural, social, political and technological developments then architects and designers are also part of those developments, not just conduits through whose (neutral) hands change is a given a functional form.

And such critical reflections were the one thing we genuinely missed in Bauhaus Imaginista, the theorising and reflection in the exhibition largely placing Bauhaus on the correct side of history, as an institution, individuals, overtaken by geo-political-economic events outwith its/their control. Which for us is, when not pure imagination, that's too harsh, then is certainly an image marginally disengaged from reality.

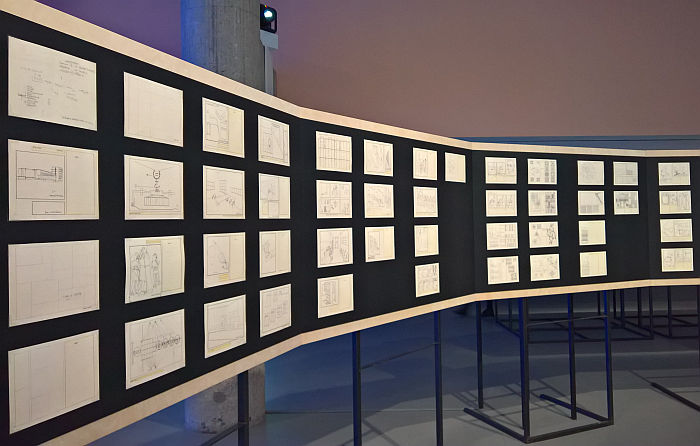

An open and approachable exhibition which makes intelligent and pleasing use of the HKW's exhibition spaces, spaces which owing to their inherent sterility can be difficult to fill; with its many videos, installations, books, plans, and theory, Bauhaus Imaginista is however very much an exhibition to which you need to bring a goodly bit of time and a clear, focussed, interested, critical, questioning mind. Not least to read your way through the texts in the accompanying exhibition guide: bilingual English/German texts which are clear, comprehensible and succinct, but numerous and necessary. Or put another way, it's not an exhibition of Bauhaus memorabilia that can be inattentively whizzed through, its not Bauhaus Instagramista, it's a little more demanding. Which is what it wants to be. Which in many regards it has to be. And which we're glad it is. Would be disappointed if it wasn't

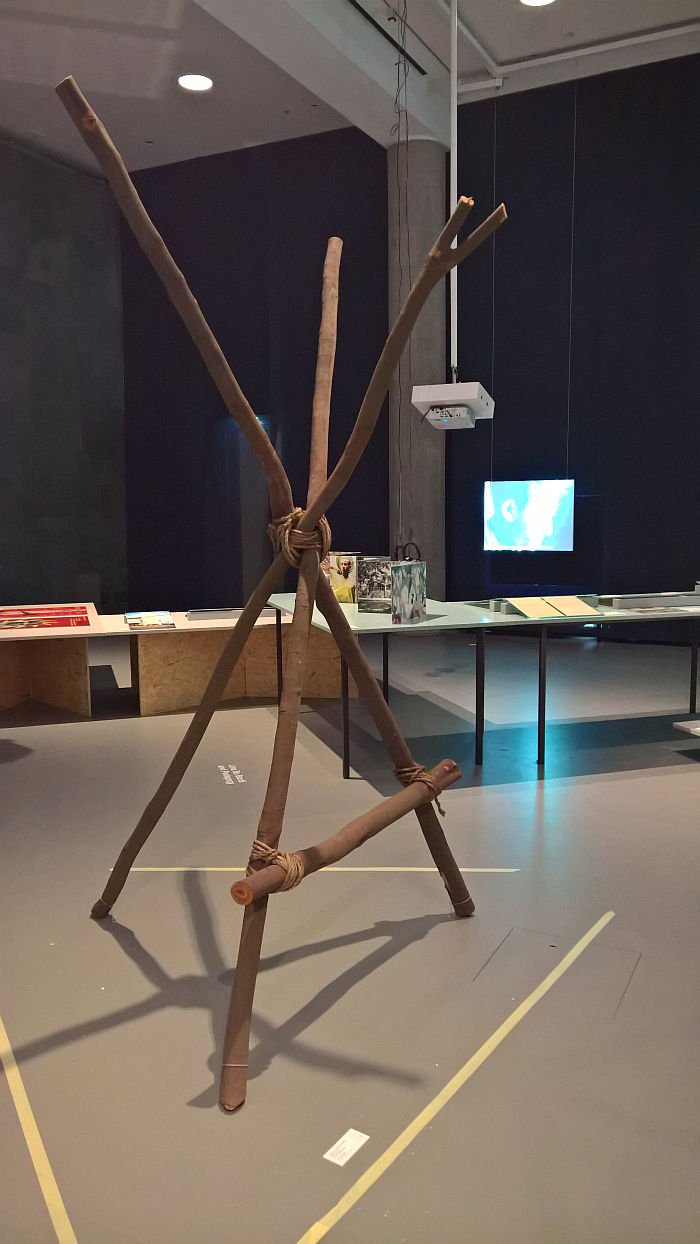

Which isn't to say there aren't a few objects which allow one to briefly escape the narrative, to let your imagination drift in new directions, to ignore the contexts and reflect on architecture and design purely as objects. For our part we were particularly taken by, and amongst other works, a charming low stool created at Kala Bhavan in the 1930s by Rathindranath Tagore; Hannes Meyer's draft for a Bauhaus book, and which includes some absolutely delicious concepts; and the 1967 "Roadside Chair" by Lina Bo Bardi, a work inspired by vernacular traditions and which is just one of the most joyous celebrations of furniture design, a work whose simplicity of construction and form not only stands polar to the endless monumentality of the object, but also underscores the necessity of honesty in furniture design. And, obviously, Vidal Sassoon, a man who also has the air of the imaginary around him. The hair of the imaginary? Sorry.

Which we guess just leaves one question unanswered, does Bauhaus Imaginista bring us closer to a more substantive understanding of Bauhaus?

Arguably not.

Or perhaps better put, arguably not, but does help us move towards a better contextualisation of Bauhaus. As an exhibition Bauhaus Imaginista explores Bauhaus in relation to the processes from which it arose, which accompanied it and which it informed, without ever letting it become in any way dominant. Bauhaus is everywhere in the exhibition, but rarely alone, and thus Bauhaus Imaginista helps demystify Bauhaus, dissolves the image of Bauhaus as a singular, miraculous institution, as something uniquely definable outwith its buildings, works and biographies, and thereby allows it to merge effortlessly into the incessant evolution of understandings of art, architecture, craft and design.

Or perhaps better, better put, walking round Bauhaus Imaginista our principle thought was, what if Bauhaus really had never existed?

Can we imagine contemporary art, design, architecture without Bauhaus? Can we imagine contemporary society without Bauhaus?

Yes.

And through being able to, can approach a better understanding as to what Bauhaus really was. And how Bauhaus undeniably exists.

Bauhaus Imaginista runs at the Haus der Kulturen der Welt, John-Foster-Dulles-Allee 10, 10557 Berlin until Monday June 10th

Full details, including information on the accompanying fringe programme, can be found at www.hkw.de

And full details on the Bauhaus Imaginista project, including numerous texts, photos and documents, can be found at www.bauhaus-imaginista.org