"How far can we entrust the machine to design?" asked the American architect Louis I. Kahn in context of the 1968 conference Computer Graphics in Architecture and Design.

In his opinion, not much.

"The machine can communicate measure, but the machine cannot create, cannot judge, cannot design. This belongs to the mind".1

And today?

With the exhibition The Architecture Machine. The Role of Computers in Architecture, the Architekturmuseum der TU München explore the (hi)story of the computer in architecture, the (hi)story of architecture in the computer and considers the question, if the course of those (hi)stories has seen the computer take control of architecture or architecture tame the computer.......?

As oft noted, the ubiquity and omnipresence of computer technology in our contemporary world can lead one to forget that computers are relatively new, or better put digital computers are relatively new; analogue computers have been known throughout history, and the Babylonians made regular use of algorithms. Just not to try to sell you things, decide if you qualified for a mortgage or grade your exams; but rather to help us all better understand the world.

Which might be worth remembering.

First in the 1950s did digital computer technology begin, when only very slowly, to creep out of university and commercial research labs and to make itself at home in wider society, including in architecture: the first design/architecture software, Sketchpad, being developed by Ivan Sutherland at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, MIT, in 1963; the aforementioned 1968 Yale School of Art and Architecture conference was one of the first major international, inter-disciplinary, conferences to consider the, possible, joint, future of architecture and computers; and was quickly followed by Nicholas Negroponte's 1970 book The Architecture Machine, a project developed, as with Sketchpad, at MIT, and a work which he described as "for people who are interested in groping with problems they do not know how to answer".2 And as Chris Stevens teaches us, in life, “it's not the vision, it's not the vision at all, it's the groping, it's the groping, it's the yearning, it's the moving forward”.

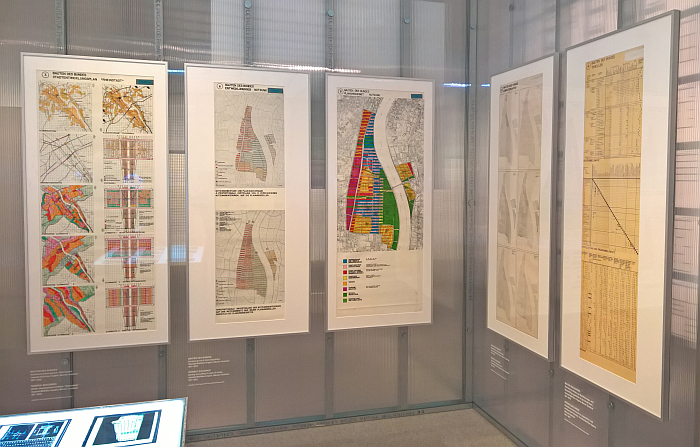

Borrowing the title, if not necessarily (fully) the ethos, of Negroponte's project, The Architecture Machine moves forward from the groping and yearning of the early pioneers to discuss developments in the relationship(s) between architecture and computing over the past 60-ish years as exemplified and elucidated by some 40 international projects, and in the course of 4 inter-twinned, free flowing, chapters: Design Tools, Storytelling Mediums, Interactive Communication Platforms, and as the starting point of both the exhibition and the relationship between computers and architecture: Drawing Machines.

One of the first questions 1960s architects asked themselves, as indeed did most everybody in the 1960s, was, where and how could and should we employ this developing technology?

For a Louis I. Kahn the answer, or at least a part of his answer, was not in designing.

And he wasn't alone. In architecture, as in all creative professions, there was wide, and deep, scepticism as to how the objective calculating machine could replace the subjective poetic human in creative processes without losing the emotional connection that exists?, is essential?, between a work of art, architecture, design, music and the individual. But that's a discussion for another day.

The discussion for this day is that others were more pragmatic, and pragmatists who started their considerations with that most basic of architectural design tasks, drawing: Sketchpad understanding the development from analogue to digital very literally and allowed the architect to draw directly on to the computer screen with the aid of a so-called light pen. Which not only has a certain undeniable logic to it, but is another fine example of the skeuomorph in design as an aid to easing the uptake of new technology.

Whereby, for all its newness, all its revolution, Sketchpad was initially only 2D, and thus of limited value, a limited example of computers in architecture; however, 3D computer drawing developed relatively quickly, as did the increased capacity of computers to undertake the measuring Kahn had trusted them with, and that in ever increasing degrees of complexity. Developments in hardware and software which saw the computer advance to not only become an architectural Design Tool, but also an analysing, modelling and rendering tool.

Developments followed in The Architecture Machine via project's such as, and amongst many others, Otto Beckmann's Imaginary Architecture studies from the 1970s which sought to harness, still very experimental, computer technology for the generation of, very experimental, formal expressions; Cornell in Perspective from 1969-72, one of the first animated architectural walk-throughs, a project generated on computers but presented as an analogue 16mm film, each frame photographed from the monitor, and a project digitalised for the first time in The Architecture Machine; or Frei Otto and Carlfried Mutschler's Multihalle in Mannheim from 1972-74, one of the earliest examples of the use of computers to calculate the angles of structural connections and to generate construction plans. And projects which help not only elucidate how the early pioneers groped their way forwards, but for all very neatly demonstrates that early computer technology was still an awful lot of work, was a very manual, and often analogue, process. The computer may have become an aid to architects and architecture, but not a self-sufficient, pro-active, one.

And for all required computer programming skills; lest we forget, we are still in the very early days of computer technology, in an age when the use of computers in any sphere was still very much something for those initiated in the black arts, an age of mainframes and plotters, an age of primitive languages with limited vocabularies, an age of high expense and low capacity, an age before there was an app for that.

However, as computers became ever more powerful, ever smaller, ever more user friendly, ever more self-sufficient through ever new software, and for all as ever more of us began to not only consider the possibilities of computers in our daily lives, professional and private, but to understand and accept the inevitability of such, so did computers move increasingly quickly into ever more areas of our lives.

And ever more areas of architecture.

For all that architecture is primarily about designing the built environment and creating shells within which we can live, work, learn, convalesce, consume, exercise, et al, as The Architecture Machine very tacitly implies, the (hi)story of the relationship(s) between architecture and computers isn't just to be understood in the terms of the development of new forms, forms incalculable with analogue computing technologies; nor only in helping evolve understandings of construction processes, for example in advancing modularity in architecture; nor nor only only in easing, automating, much of the workflow of architecture: but also in terms of evolutions in the wider practice and industry of architecture.

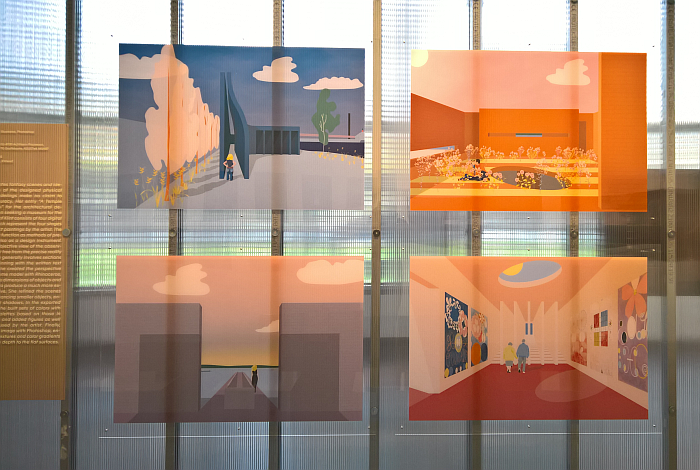

Including evolutions in the presentation of architecture, both internally, amongst those directly involved in a project, and also externally, to the wider society; evolutions which have led to changes in how architecture, and architects, are popularly perceived.

Throughout history architects have sought to visualise their projects in a manner more than the purely technical, to make their plans accessible to more than just architects, engineers and surveyors, and for the majority of that history sought to achieve such through the use of orthographic projections and scale models to set the works in a spatial context; however, there is only so much you can do with such analogue methods, only so far you can allow the visitor to engage with the project. Regardless of how realistic your model trees are.

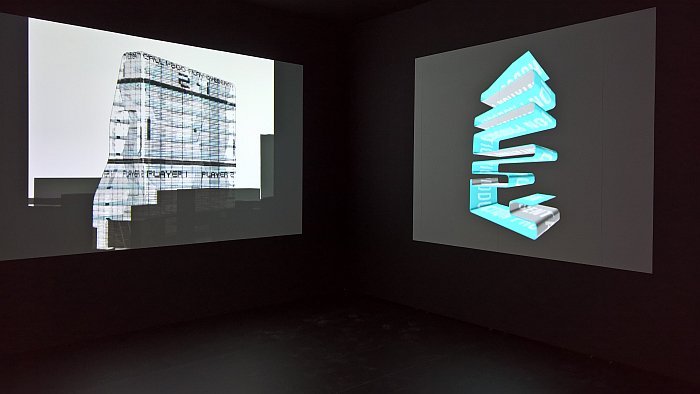

Computer rendering and computer animation brought a notable spring forward. A spring that has become ever longer as hardware and software have become ever more powerful and complex. A spring that as it has increased in length so has its importance extended, has become one of the primary methods by which architecture is popularly consumed and understood.

And a spring explored, discussed and measured in The Architecture Machine through a varied selection of animations and renderings, and which aside from helping one understand the variety of commercial visual presentation formats employed in contemporary architecture, also posses the question as to the why? Why all the effort?

The answer, or at least a large part of the answer, is Storytelling, that ubiquitous tool in the contemporary marketeers bag of tricks and via which architects seek not only to visualise their projects in a manner more than the purely technical, but to bring emotion into a project. Or at least the emotive, the question of emotion in architectural renderings and animations is a complex beast. And Storytelling a subject which could see us go off on a very, very large tangent, a tangent we very, very much want to follow, but which will take us far, far away from the Architekturmuseum der TU München. And so will do so on another day.

For here we will, regrettably, limit ourselves to the question, why not just use the possibilities of 3D modelling and animation to soberly visualise the internal relationships within a building and thus allow for an understanding of if that building is suitable for its intended purpose. And, more importantly, if it is going to be adaptable enough as that intended purpose, invariably, becomes an unintended, but more necessary, practical, purpose. Rather than present an emotion laden idealised vision of a future no one can predict?

Would that not be of more benefit to the discussions on both the merits, or otherwise, of a particular project and the wider relationships between architecture and society, the consequences of architecture, than the telling of a story?

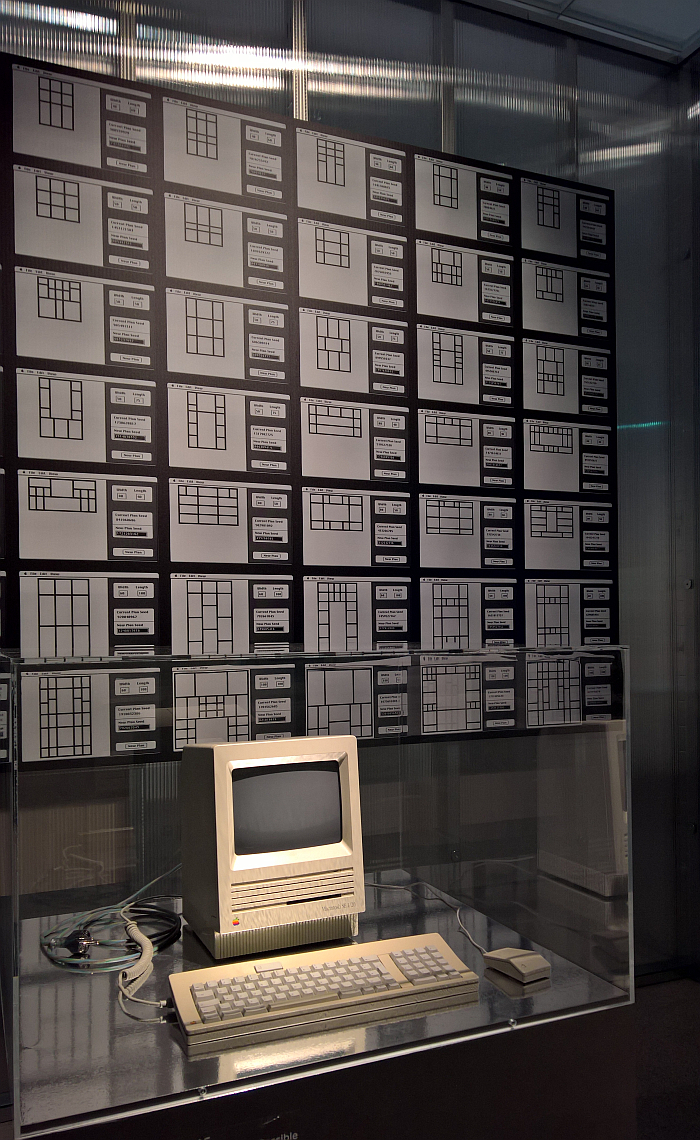

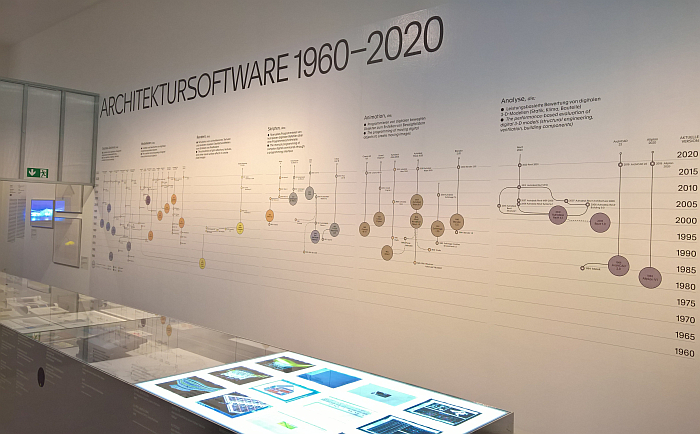

In addition to its principle narrative The Architecture Machine also takes a couple of entertaining detours, the largest being through the (hi)story of the development of architectural software; which, yes, is that which in many regards underscores the rest of the narrative, that which has allowed that narrative to develop and evolve in the way it has. But which is also very much a narrative for itself. And a narrative, according to the curators, told for the first time in its interconnected fulsomeness in The Architecture Machine.

And a telling which, yes, on the one hand is a list of computer programmes whose names mean absolutely nothing to those who don't use them, and which, yes, on the other hand does feel like it will inevitably become a (socially distanced) meeting point for architects over the age of 40 both reminiscing with colleagues over the age of 40, "ooohh, do you remember when we first got that? And that?" and admonishing colleagues under the age of 40, "you don't know how lucky you are, when I was your age......" But which on the all important third hand, and thanks to the succinct, informative, explanatory texts, and the presentation of brochures, projects and other supporting material, is an easily comprehensible explainer, for lays and professionals alike, both over and under 40, as to not only how the scope of available software has evolved and how that evolution has impacted on architectural practice, but also both the active role of architects in those evolutions, and the links between the evolutions of architectural software and evolutions of software for the product and industrial design industries, and thus the inherent closeness of the disciplines. A closeness that, arguably, software similarities can only intensify.

Just as important as evolutions in software for the development of architectural computing, indeed all contemporary computing, is and was evolutions in hardware and peripherals. Including the mouse. The Architecture Machine presenting a brief exploration of the evolution of Mus computeralis, an exploration which very satisfyingly allows for a better understanding of the differing forms and functionalities the computer mouse has expressed since it first appeared in the 1960s. And in doing so poses the question how we got to where are we today? Given that the computer mouse is an essentially archetype free object, and one that developed a (+/-) universal form relatively quickly, the computer mouse in all its contemporary familiarity embodies some interesting considerations as to how contemporary design standards and norms become set. Who makes the decisions? Especially when as The Architecture Machine makes clear, there are alternatives. Including alternatives that would appear more logical in specific contexts, such as architecture, than our standardised Mus.

Presenting its narrative more or less chronologically, not directly, within the four chapters there is also an independent chronological progression; however, in that it opens with Sketchpad from 1963 and that one of the last exhibits is 2009-2012 Barclays Center in Brooklyn by SHoP et al and its employment of an app to document and visualise the construction process, the overall movement through the space is very much chronological.

And much as The Architecture Machine is about the developments and evolution in the (hi)story of the computer in architecture and the (hi)story of architecture in the computer, it is also an opportunity to explore and reflect on the 40 projects individually, and for all on the 40 projects as moments in the wider history of the development and evolution in architecture since the 1960s; moments that may be, are, inextricably related to the development of computer technology, but are just as relevant, and interesting, in their own right.

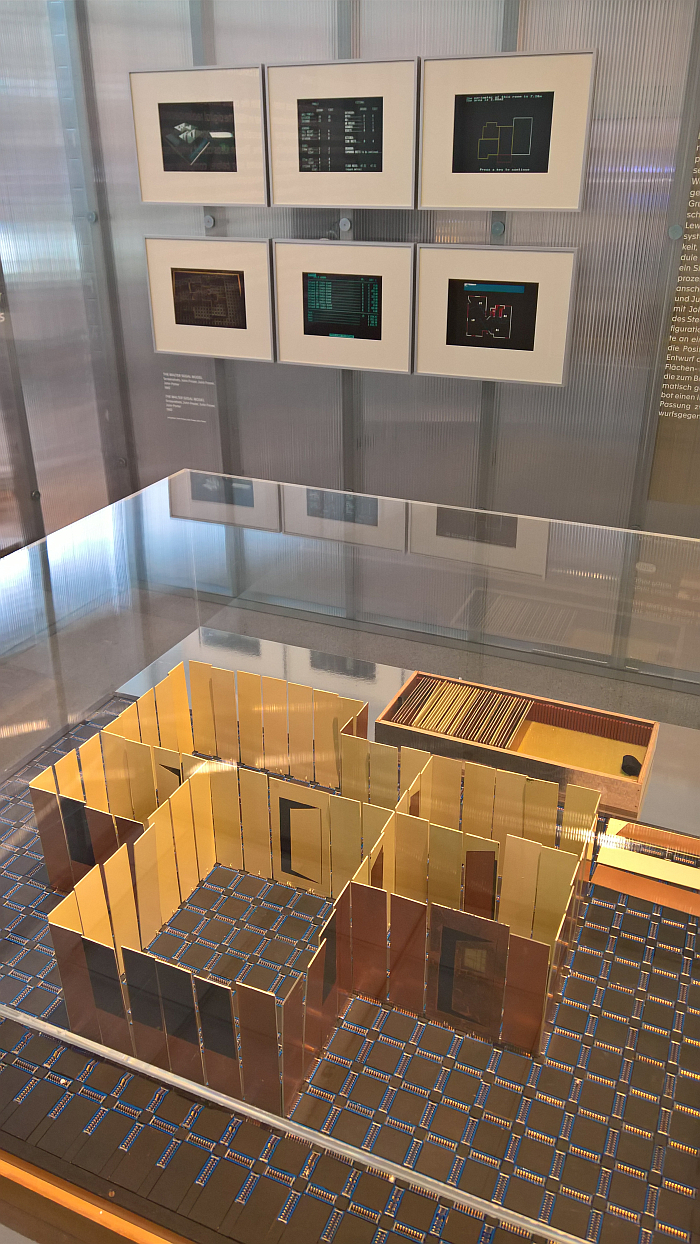

Projects such as, for example, the 1982 Walter Segal Model by John Frazer, Julia Frazer and John Potter; a development of Walter Segal's analogue 1950s self-build system and which in its digitalised version saw houses planned by inserting tabs representing walls, doors, windows, etc, into a computer board to create the desired house. Once completed the software checked the validity of the design and if all was good generated floor plans and costings. And a project which is not only the most joyously intuitive of systems, nor only a very satisfying alternative to the Storytelling emotions of rendering and animations, but also raises memories of both Balkrishna Doshi's Aranya Low Cost Housing community in Indore, India, a modular, analogue, system, but where family's could and can devise their own home based on their needs and resources, and also the Elementa construction system developed in 1970s West Germany by Neue Heimat, and the 1970s East German Variables Wohnen project developed by Rudolf Horn et al, and which both allowed for the development of variable floor plans, and thus individually configured flats, in the new high rise blocks of the period. And thus considerations on the, we'd argue, undeniable logic of buildings planned to be variable. Considerations approached from a different angle in the 1992 Possible Palladian Villa project by George Heresy and Richard Freedman, and which employed the 16th century construction principles of Andrea Palladio as the basis for the automatic generation of buildings based on parameters defined by the user, and which in doing so poses the question, who needs architects? Or rather, who needs 21st century architects when you've got 16th century architects?

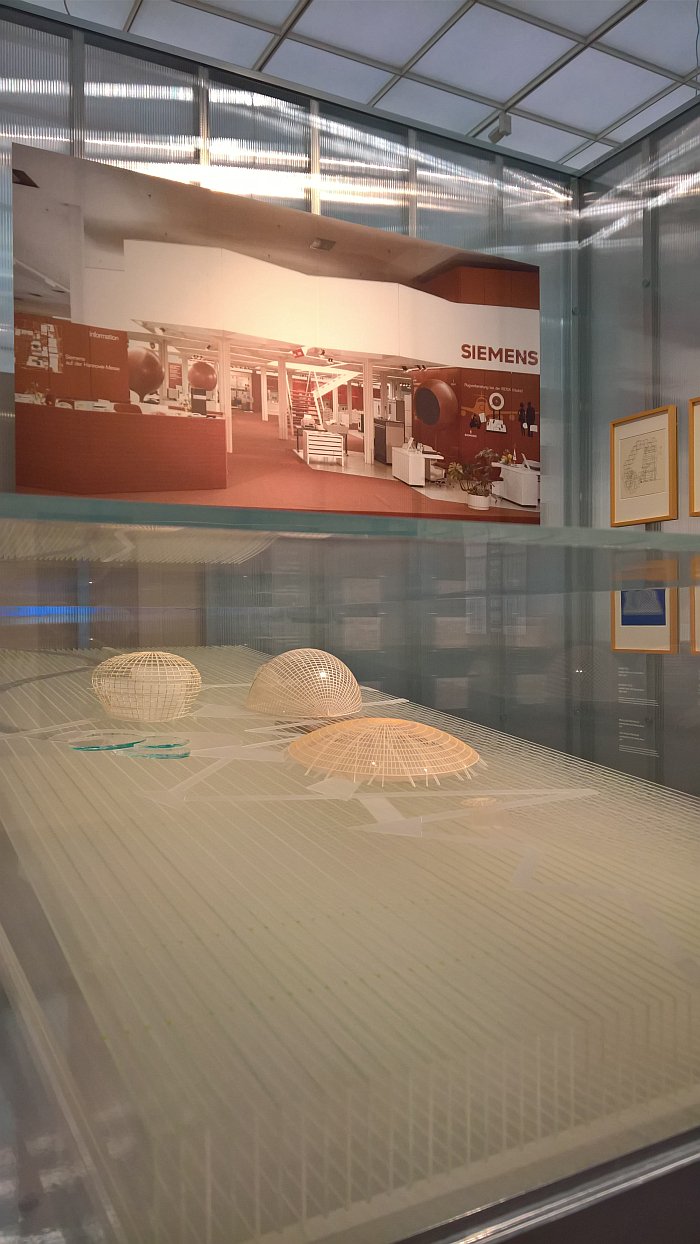

Elsewhere, our attention was particularly caught by the Siemens Pavilion for CeBit 1970 in Hannover by Ludwig Rose, Georg Nees and Jost Clement, the first building in Germany designed by a computer, and a work which helps underscore the historic importance of trade fairs in the development of architectural understandings, focuses attention on an age when the buildings nations and conglomerates presented themselves in at trade fairs were as important as that which was presented. Yes, the vast majority were subsequently dismantled, with the associated ecological impact considerations; but where does the very real impetus in architecture, as in constructed rather than theoretical architecture, that once came from the trade fair come today?

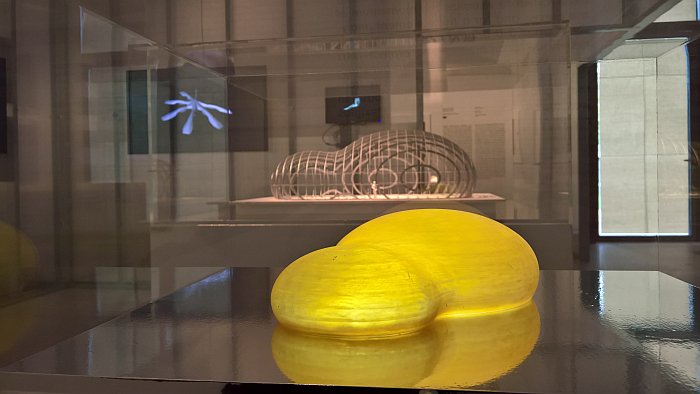

Or, and staying with trade fairs, the, so-called, BMW Bubble by Bernhard Franken et al which was first presented at the 1991 Frankfurt Motor Show and which aside from the numerous novel uses of computer technology involved in its development, is represented in The Architecture Machine as a 3D printed model, one of the first 3D printed architectural models. And which leads on to further considerations on 3D printing in real rather than modelled architecture.

Considerations supported, as it were, by a wooden joist from SHoP's 2000 Dunescape project, a project which although very neatly demonstrating how computer technology can be used to help simplify the construction process, is for all a very nice example of a project designed digitally but built analogue. And thus reflecting a common complaint in these dispatches, that we still build brick on brick on brick, joist in joist in joist; and that despite the, we believe, popular understanding of the advantages of more industrial construction processes, and the enhanced possibilities in context of industrial construction enabled by digital computer technology. Yes, popular understanding of the advantages, except amongst bricklayers, joiners, roofers etc; but what happened to all the draughtsmen who used to create architectural blueprints in the days before the digital computer?

Very much an architecture exhibition, i.e. lots of models, plans and films et al, which isn't a complaint, just an observation, The Architecture Machine provides for a well paced, accessible, entertaining and thought provoking journey through the (hi)story of the computer in architecture and the (hi)story of architecture in the computer, or more accurately put through the (hi)story of the computer in architecture and the (hi)story of architecture in the computer as exemplified by 40 experimental and/or high-profile, signature projects, one must never forget that the architecture the vast majority of architects are involved with, and correspondingly their relationship(s) with computers, is a lot more mundane; and which in doing so provides space and time for your own reflections on the myriad themes and topics therein.

Reflections aided and abetted by the concise and clearly comprehensible bilingual German/English texts; and space and time aided and abetted by the exhibition design by Florian Bengert/BNGRT with its use of translucent plastic walls, and which not only allows the, relatively, densely packed exhibition hall to remain light and open, but also allows for very easy social distancing without the feeling of social isolation. Which we don't believe was part of the original brief, but is a not unimportant component of the realisation.

If we did miss one-thing it would be a pre-history of digital computer technology in architecture. A brief scene setting as it were. Not necessarily a discussion on how in centuries past, and indeed up until the 1970s, large, complex structures were planned and executed without digital computing; but much more those precursors who helped explain to the first generation of computer architects the possibilities before they (fully) existed, precursors such as, for example, a Konrad Wachsmann, or a Superstudio whose late 1960s photomontages and films so succinctly predict the coming computer animation. And its Storytelling.

If we did miss two-thing it would be engineers. Yes, in numerous projects the responsible engineers are named; but the focus on architects tends to undervalue the role of engineers in architecture. And as we all learned from the exhibition Visionäre und Alltagshelden. Ingenieure – Bauen – Zukunft at the Oskar von Miller Forum, without engineers there would be no architecture. Or at least no built architecture. Just plans. The digital computer being every bit an Engineering Machine as an Architecture Machine.

And an Unceasing Machine.

In his The Architecture Machine Nicholas Negroponte noted that, "you will find that this book is all beginning and no end",3 the Architekturmuseum der TU München's The Architecture Machine follows Negroponte's lead, and makes very clear that in architecture, as in all spheres, developing technology, developing computing technology, means that however far one believes oneself to have travelled, one is always on the threshold of new possibilities, of new realities, new understandings.

And in doing so helps one approach an understanding that the place developments in digital computing have brought contemporary architecture isn't the end of the narrative, isn't the end of the groping, the yearning, the moving forward, that the relationships between the computer and architecture are still developing.

And also helps one approach an understanding that coming Artificial Intelligence will both open a new chapter in the (hi)story of the relationships between computers and architecture, and also take us back to the questions of where and how could and should we employ this developing technology?

If computers have minds, if computers are subjective, who needs architects?

Answering that question requires understanding what architects do, the function of architects in society, the value of architects to society.The function and value of architects to and in architecture.

And thus ultimately the more decisive developments in the ongoing (hi)story of the role of computers in architecture, will be those in the popular perceptions of architecture, and in how far we as a society can entrust the architect to design.....?

The Architecture Machine. The Role of Computers in Architecture runs at the Architekturmuseum der TU München in der Pinakothek der Moderne, Barer Str. 40, 80333 Munich until Sunday January 10th.

Full details, including information on the accompanying fringe programme, can be found at www.architekturmuseum.de/the-architecture-machine

And as ever in these times, if you are planning visiting any exhibition please familiarise yourself in advance with the current ticketing, entry, safety, hygiene, cloakroom, etc rules and systems. And during your visit please stay safe, stay responsible, and above all, stay curious......

1Louis I. Kahn, Panel Discussion – The Past and Future of Design by Computer, in: Proceedings of the Yale Conference on Computer Graphics in Architecture (April 1968), New Haven CT 1969, S. 98 quoted in Georg Vrachliotis, Architekturmaschine. Individualisierungssyteme, Arch+, December 2018, 36–43

2Nicholas Negroponte, The Architecture Machine. Towards a more humane environment, MIT Press, 1970, A Preface to a Preface

3ibid