"March is the Month of Expectation. The things we do not know",

opined once the American poet Emily Dickinson.1

Easily enough resolved!!!

And no, not by "Persons of prognostication", whom one should definitely always "show becoming firmness"; but by visiting an architecture or design exhibition and approaching that which you don't know via your own inquiry and questioning and reasoning.

Our five recommended locations for transforming expectations into knowledge in March 2023 can be found in Berlin, Espoo, New York, Nyköping and Weil am Rhein.......

First off we have to say that we really, really, really, don't like the name: Retrotopia sounding to us like the sort of deplorable, despicable, "vintage" furniture shop that sells utter tat for outrageous prices to those easily-led personages impressed by Instagram. While also tending to imply that the presented works and positions have no contemporary relevance, are trapped in a past from which they once sought to escape, but from which they never can. Are trapped in pre-1989 Socialist Spaces. And also tending to imply that pre-1989 design in eastern Europe isn't as valid as pre-1989 design in western Europe. Which we're absolutely certain isn't the intention of the exhibition.

Certainly isn't our reading of the exhibition's intentions.

A reading of the exhibition's intentions which we very, very, very much do like.

Developed by the Kunstgewerbemuseum, Berlin, in cooperation with a pleasingly wide variety of institutions from Slovakia, Hungary, Lithuania, Ukraine, Slovenia, Czech Republic, Estonia, Poland, Croatia and East Germany, that latter in the form of the Museum für Utopie und Alltag, Eisenhüttenstadt, the exhibtion promises to explore design in eastern Europe between the 1950s and the 1980s from two perspectives: one the one hand via realised and unrealised examples of architecture, interior design and urban planning projects, as best we can ascertain the focus is very much on the Spaces of the title, and on the other had via a discussion on the networks of design institutions, design schools, design collections, design exhibitions, exhibition designs, etc that linked the region and which informed and advanced the various discourses both within the individual countries and also across not only the, then, socialist region but also with, and into, the, then, capitalist world beyond that Iron Curtain.

And which as such, as a mix of projects and positions juxtaposed by the design profession, professional design, context in which they arose, whereby one suspects the political, social and economic contexts will also be mentioned, should allow not only for a comprehensive introduction to, and, importantly, more probable insights into the (hi)story of design in a time and place that design (hi)stories only very rarely seriously, critically and objectively venture, but also allow for access to better appreciations that, and for all the invariable similarities, design in pre-1989 eastern Europe was neither a homogenous mass, nor something widely different to that being practised and propositioned in pre-1989 western Europe. And thereby should allow for an underscoring that the big difference, the key difference, between design in pre-1989 eastern Europe and design in pre-1989 western Europe is in perceptions and receptions of pre-1989 design in eastern Europe and pre-1989 design in western Europe since 1989.

Why you would want to call that space Retrotopia, we no know. But maybe after viewing it the reason will be become as clear as the insights its promises to provide.

Retrotopia. Design for Socialist Spaces is scheduled to open at the Kunstgewerbemuseum, Matthäikirchplatz, 10785 Berlin on Saturday March 25th and run until Sunday July 16th. Further details can be found at www.smb.museum/retrotopia

While design from Finland is without question an Aino Aalto, an Alvar Aalto, a Tapio Wirkkala, an Ilmari Tapiovaara, it's also a Yrjö Kukkapuro. If a Yrjö Kukkapuro who regularly gets overlooked in the popular viewing of design from Finland. And by his 1960s Karuselli lounge chair. A work that arguably casts as large, if glorious, a shadow over his oeuvre as it does on your living room wall.

With Magic Room, EMMA, Espoo, should alter that. Should allow Yrjö Kukkapuro, his positions, approaches, relevance to appear in that light in which they deserve to stand. And that via a presentation that promises to introduce not only the broad, divergent Kukkapuro oeuvre, but for all to introduce it in context of two key influences on that oeuvre: art and his wife, Irmeli Kukkapuro, the pair meeting as students at the Institute of Industrial Art, Helsinki, in the 1950s, and working closely together, inspiring and informing one another, over the next six decades, while very much both pursuing their own paths, Irmeli as a graphic designer and artist, Yrjö as (most popularly) a furniture designer.

And an influence of art, for all modern and postmodern art, EMMA will aim to discuss both through Kukkapuro's design in context of art, and also through works of art by both Kukkapuro's contemporaries and by contemporary artists of various hues from Finland and, let's say, the Gulf of Finland, including, and amongst others, Jacob Dahlgren, Tarja Pitkänen-Walter, Vladimir Kopteff, Kristiina Nyrhinen or Osmo Valtonen; and thus a presentation of artworks which should not only enable differentiated perspectives on the motifs and motivations of Kukkapuro's design but also help better locate Yrjö Kukkapuro in the wider artistic, creative, practice and positions since the 1950s.

Yrjö Kukkapuro – Magic Room is scheduled to open at EMMA – Espoo Museum of Modern Art, Exhibition Centre WeeGee, Ahertajantie 5, Tapiola, Espoo on Wednesday March 1st and run until Sunday January 28th. Further details can be found at https://emmamuseum.fi

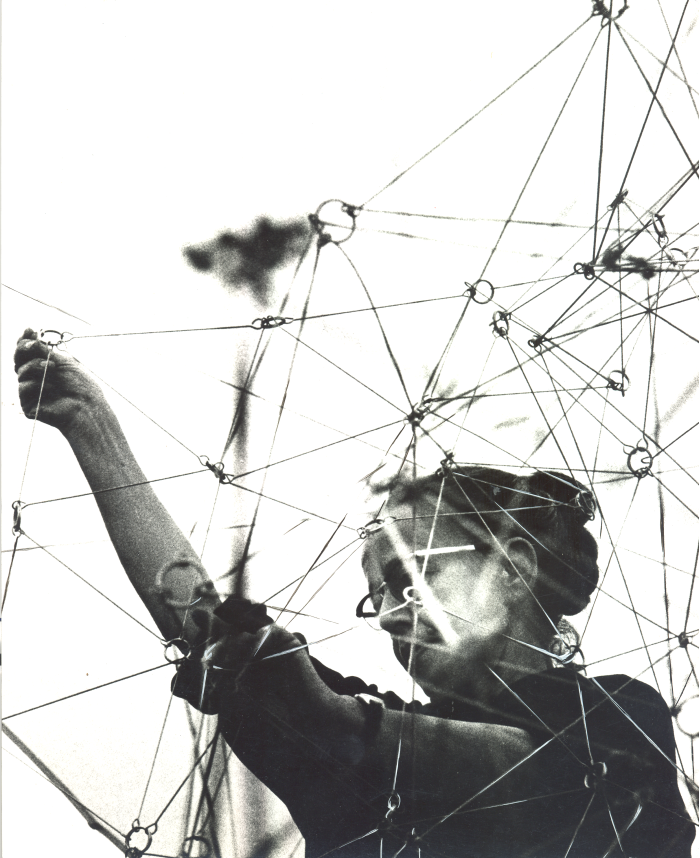

Born in Hamburg in 1912 Gertrud Goldschmidt a.k.a. Gego studied architecture in Stuttgart, before, and more or less immediately upon her 1938 graduation, she was forced to flee from the Nazis, finding refuge in 1939 in Venezuela. And where she remained for the rest of her life. And from where she developed into one of the more interesting and informative creative researchers in context of spatial volumes, of spatial systems, of spatial relationships. On space as anything but a passive, static, unresponsive, empty void. Creative research, arguably, carried out most famously through her numerous steel wire constructions; and research which neatly set art, architecture and design in discourse with one another and thereby enabling new lines of thought to be identified and pursued,

In addition to a presentation of some 200 objects including, sculptures, drawings, textiles and photos of Gego's installations from the 1950s to the 1990s, and which should allow for a comprehensive introduction to the life, work, relevance and legacy of Gego, Measuring Infinity also promises to place a particular focus on discussing Gego's work in context of the contemporaneous artistic movements and positions of the Latin America of the second half of the 20th century, a context in which her work isn't always necessarily approached and considered, and which in doing so should not only allow for an alternative reading of the Gego's canon, but also provide access to an alternative introduction to 20th century Latin America art.

Gego: Measuring Infinity is scheduled to open at the Guggenheim Museum, 1071 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10128 on Friday March 31st and run until Sunday September 10th. Further details can be found at www.guggenheim.org

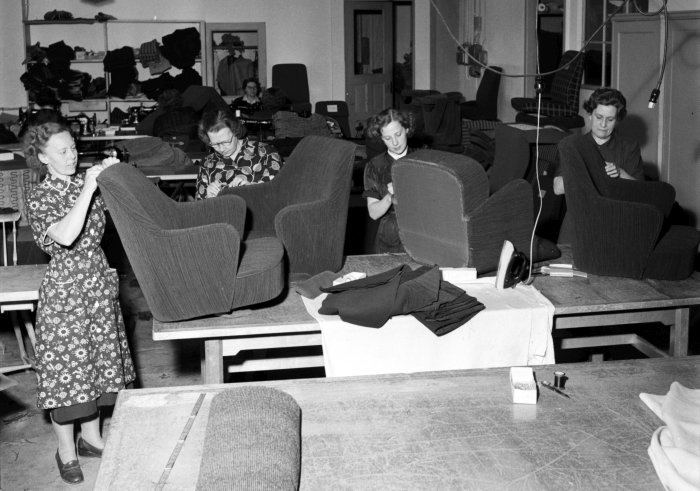

The Nordiska Kompaniet, NK, department store was founded in Stockholm in 1902, moved in 1915 to the premises on the city's Hamngatan, directly opposite the Kungsträdgården park, that it still occupies, in every sense of the word, and from where it became one of those retail institutions that has not only accompanied and reflected but also informed the development of Sweden. Including the development of Swedish interiors and furniture, an aspect of the (hi)story of NK, and Sweden, that Sörmlands Museum, Nyköping, aim to explore and elucidate.

And that in the city where much of the practical realisation took place: in 1904 NK opened furniture workshops in Nyköping which over the following decades produced furniture designed by the likes of, and amongst many, many others, Carl Malmsten, Carl Bergsten or Axel Einar Hjorth; furniture which played a key role in the development of understandings of and positions to furniture and interior design in Sweden in those early 20th century decades in which department stores, in Sweden and globally, were the locations where a greater number of people, certainly better off individuals, bought their furniture and home textiles.

And while, yes, post-War the furniture and interior design discourses in Sweden did become ever more dominated by IKEA, NK remained relevant, not least through the myriad works designed by the likes of Bengt Ruda or Kerstin Hörlin Holmquist, while with the NK-BO platform under the direction from 1947 of Lena Larsson, NK not only helped provide visibility and validity for a coming generation of post-War Swedish designers, but with the Trivia collection by Larsson and Elias Svedberg helped introduced and popularise flat-pack furniture to and in Sweden.

Promising a presentation of some 150 items realised in NK's Nyköping workshops between 1904 and their closure in 1973, NK:s möbler should not only allow for an excellent introduction to NK:s möbler, and to the place of NK and NK's furniture in the development of furniture and interior design in Sweden, but in doing so should also allow for an alternative perspective on the much told tale of furniture and interior design in Sweden and thereby allow for more probable appreciations of furniture design in and from Sweden. While also giving a face and identity to at least some of the many otherwise anonymous men and women who worked in NK Nyköping workshops and whose skill and talents are every bit a part of the (hi)story of furniture design in Sweden as are those of the designers and architects.

NK:s möbler is scheduled to open at Sörmlands Museum, Tolagsgatan 8, 611 31 Nyköping on Saturday March 11th and run until Sunday March 10th 2024. Further details can be found at www.sormlandsmuseum.se

In the beginning there was the countryside, nature, fruit orchards and vegetable plots before humans, in that singular way they have, began both industrialising and optimising the countryside, nature, fruit orchards and vegetable plots, and also romanticising the countryside, nature, fruit orchards and vegetable plots of old in walled, fenced, private dominions. And slowly the garden as we know it today arose and became not only the location is, but the concept it is, the symbol it is, the discourse it is.

With Garden Futures: Designing with Nature the Vitra Design Museum promise an exploration of the garden as a document of societies past, the garden as a mirror of contemporary society, the garden as a question of future society, the garden as a location of creativity, the garden as a motivator, stimulus, medium for creativity; and which in addition to garden design per se, and as approached by creatives as varied as, for example, and amongst many others, Barbara Stauffacher-Solomon, Alvar Aalto, Derek Jarman or Luis Barragán will also explore gardens in context of subjects such as, for example, colonialism, social reform, climate change, or human relationships with the natural world.

And which in doing so promises to help elucidate that a garden is more than just plants, trees, compost and an ever lengthening to-do list. While also being plants, trees, compost and an ever lengthening to-do list.

And while the motivation for Garden Futures may or may not have been the recently planted garden by Piet Oudolf in front of the VitraHaus that now provides for an added attraction on the Vitra Campus, said Oudolf Garden, certainly offers a not inappropriate, nor uninteresting, location for a little post-exhibition reflection and consideration on that experienced within the Vitra Design Museum.

Garden Futures: Designing with Nature is scheduled to open at the Vitra Design Museum, Charles-Eames-Str. 2, 79576 Weil am Rhein on Saturday March 25th and run until Tuesday October 3rd. Further details can be found at www.design-museum.de

1Emily Dickinson, March is the Month of Expectation in Martha Dickinson Bianchi, The Single Hound; Poems of a Lifetime, Little, Brown, and Company, Boston, 1915 That Dickinson's works were first published after her death in 1886, precisely dating her works isn't always easy, but it must have been written sometime in the mid-1800s