Only very few novel transport methodologies have impacted on society to quite the degree of the railway; not only did the arrival of the railway, pun intended, mean once far removed cities were now near neighbours, but also meant that the raw materials for, and the goods of, industrialisation could be easily and economically moved from location to location. And as the fledgling railway networks and systems developed so society.1

With the exhibition Futurails. Wege und Irrwege auf Schienen the DB Museum, Nürnberg, explore and discuss that development of rail networks and systems, and also initiate a discussion on rail networks and systems of the future.......

Time was when the only option of movement from town to town, or region to region, was by foot, horse, carriage, barge, i.e. slow and not particularly comfortable and not particularly suited to moving large heavy voluminous loads between any two freely defined points. Then in the late 18th/early 19th century Europe a change, a revolution, began to pick up speed when the first trains and the first rail networks and systems were developed; developments, and a period, with, and in, which Futurails. Wege und Irrwege auf Schienen opens via projects such as, and amongst others, Richard Trevithick's 1804 Pen-y-darren locomotive, widely considered the first locomotive worthy of the name; Joseph von Baader's 1822 publication Neues System der fortschaffenden Mechanik [New system of Transportation Mechanics] one of the first books to discuss railway technology and the possibilities of the railways; or the Stockton & Darlington railway in north-east England, which began operation in 1825 as the world's first public railway and which, effectively, marks the start of commercial rail transportation as we know it today.

And developments, and a period, that also mark the start of debates and discussions on the whats and hows and wherefores of trains and of rail networks and systems.

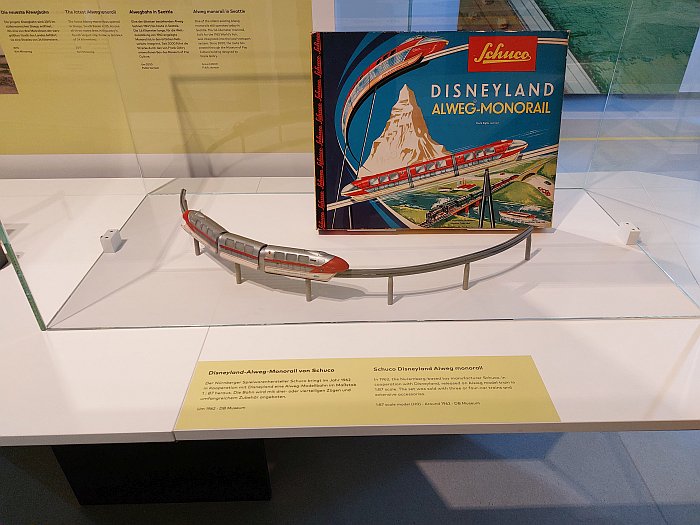

Debates and discussions on, for example, the number of rails a rail-way should have: as Futurails helps elucidate, parallel, pun again intended, to the development of, to the rise of, the two railed system as the contemporary standard, the first single rail systems were proposed, and constructed, including, for example, Henry Robinson Palmer's 1820s monorail with its carriages hanging either side of an elevated track, a system akin to the transport mule; Charles Lartigue's Listowel and Ballybunion railway in Ireland, a monorail system which was operational between 1888 and 1924; the Wuppertaler Schwebebahn opened in 1901 and still transporting passengers in suspended carriages high above Wuppertal to this day; or Louis Brennan's so-called gyroscopic monorail patented in 1903, and so-called because gyroscopes were employed to maintain balance. Which is a lot like employing magic.

Debates and discussions on, for example, propulsion systems: as Futurails helps elucidate, while the earliest rail systems such as, for example, the Linz-Budweis railway which opened in 1832, were powered by horses, were literally one or two horse power, and were, essentially, conventional horse-drawn carriages on rails, steam very quickly became the propulsion method of choice, if one challenged over the decades by, for example, and amongst other systems, the air pressure of the so-called atmospheric railways; propellers such as, for example, those of Franz Kruckenberg's Schienenzeppelin, Rail Zeppelin, so-called on account of its form and the future it promised; or, and that means of propulsion which today is, arguably, most commonly found, electricity. Among the many early, landmark, electric train projects one finds in Futurails is the brief mention of the, then, railway world speed record of 210.2 km/h set in October 1903 between Zossen and Berlin by an experimental AEG electric locomotive, a rail speed record that sustained until 1931 when Franz Kruckenberg's aforementioned propeller propulsed Schienenzeppelin reached 230.2 km/h, and an electric train speed record sustained until 1963... 1963!!!! ... when a Japanese Shinkansen locomotive achieved 256 km/h. And a 1903 experimental AEG electric locomotive that reminds us all of those glorious, halcyon, days when there was a train between Zossen and Berlin.

Debates and discussions on, for example, the place and purpose and pertinence of railways in and to society: as Futurails allows one to appreciate, in the early decades of the railway the focus of many protagonists was primarily economic, indeed one could argue without the economic focus the railway may very well have remained a niche project amongst engineers; many early rail advocates and investors were mine and/or factory owners who needed the railways to grow and expand their business and so ensured the railways grew, while in his aforementioned Neues System der fortschaffenden Mechanik Joseph von Baader refers to railways as "Eiserne Kommerz-Strassen", Iron Roads of Commerce, via which "a new world would be opened to the market" thereby bringing "incalculable benefits for the commerce, industry, agriculture, and general prosperity of any country"2, thoughts, one must add, articulated and pursued with more than a little colonial attitude and implied hope of the appropriation of lands and resources. A not altogether altruistic motivation of early rail pioneers tending to be confirmed, for example, by the many investments made in the late 19th and early 20th centuries by European concerns and governments in railway projects in the region surrounding and encompassing the contemporary Turkey, a region rich in resources but (then) poor in transportation systems, and thus rich in opportunities for those who would build efficient systems for transporting the resources out of the region. And transporting their own goods into the region. And thoughts which counsel us all to question the motivations of our own contemporary technology advocates and investors.

Yet while the early train networks' foci was primarily goods, people have been transported since the earliest days of rail; arguably initially only the wealthy, the very wealthy, but as industrialisation increased and as society became (marginally) more diverse and as the economic need for the ready mobility of workers was understood, trains became accepted human mobility solutions, and then became the transport method of choice for a great many, certainly for long journeys, for journeys far from home; and thus over time trains and railways began to become components of the tangibility of the future, became symbolic of the closeness of the brave new world that was envisaged and impatiently awaited, representatives of the dreams and hopes of humanity. And thereby, as Futurails tends to argue, railways became cultural goods, became integral and inherent components of cultures and societies.3

Debates and discussions that as Futurails also very neatly demonstrates have never gone away: contemporary projects such as, for example, the so-called Monocab monorail, a pasternoster-esque concept being developed under the direction of a research team at the Technische Hochschule Ostwestfalen-Lippe and which is based on the gyroscopic, magic, principle of a Louis Brennan; or the super conducting magnets of the SCMaglev system developed by the Railway Technical Research Institute and the Central Japan Railway Company as an alternative high-speed propulsion system; or the so-called TSB magnetic cargo transport system developed by the German construction company Max Bögl which can very much be considered a re-imagination of Joseph von Baader's Eiserne Kommerz-Strassen for the age of standardised shipping containers, amongst many other projects, echoing back through the past 200+ years.

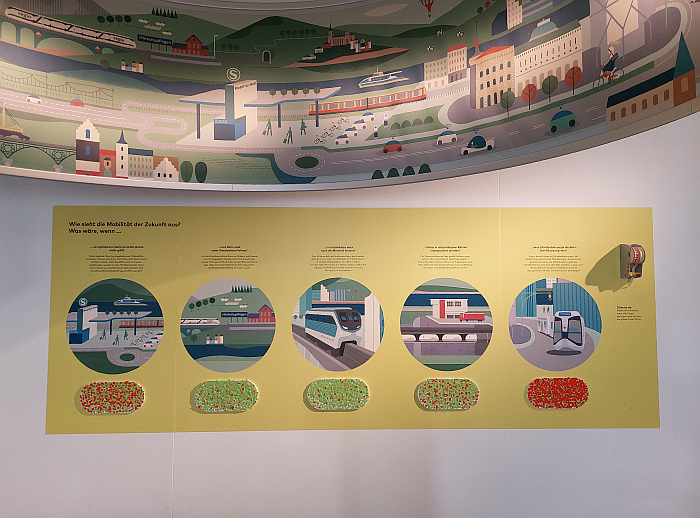

And thus debates and discussions and echoes which help Futurails elucidate that the choices previous generations faced about trains and rail networks and systems are essentially the same as we have before us; albeit today in context of our novel technologies and materials, and in context of ever more alternative mobility options, and in context of contemporary environmental, political, economic, et al realities.

And in context of contemporary, novel, social realities.

The latter an appreciation, one reinforced by the cultural context of trains and railways, that also tends to lead one to question if the influence of railways on society has been matched by an influence of society on railways? Have changes in society since the early 19th century been reflected in, embodied by, informed, changes in trains and railways? And if not, why not, shouldn't they have, what are the consequences thereof, how can contemporary society influence contemporary and future trains and rail network and systems? What is the place and purpose and pertinence of railways in a future society where the economic advantages of the train are more limited than in days past and when a myriad alternative mobility options have seen the train lose the primacy it once enjoyed?

Questions Futurails not only very much demands you pose, but assists you in formulating and approaching.

Presenting its narrative via models, photos, artefacts and easily comprehensible bilingual German/English texts Futurails is a readily accessible showcase, one that is, essentially, about technology, but isn't a showcase only for those with an interest in technology, is a showcase for all, one which never forgets that visitors with no interest in technology must leave it informed, entertained and for all engaged in its principle and extrapolated themes.

One which tends to underscore the important role novel materials and novel technologies play in developments of human systems, human society, and also tends to underscore, as also discussed in, for example, Konstantin Grcic. New Normals at Haus am Waldsee, Berlin or Back to Future. Technology visions between fiction and reality at the Museum für Kommunikation, Frankfurt, that the novel is often an idea that has been around for a while but which for a variety of reasons previously didn't, couldn't, establish itself or was previously simply impractical at a meaningful scale. And also, as with Back to Future, underscoring the important role early and mid 20th century science fiction continues to play in our understandings of future technology, and thereby enabling us to question how healthy, sensible and desirable that is. Or if we shouldn't develop our own technology. Rather than developing irrelevant flying taxis and autonomous cars. Shouldn't we develop solutions to problems rather than new problems to compound our existing problems?

One which tends to an appreciation that the path humanity is on is one of continual evolution of existing system, of the old informing the new before ceding to it, a necessary ceding; if a showcase which in its noting that the 1435 mm gauge of the 1825 Stockton & Darlington railway is, some 200 years after its introduction, still the prevailing global standard for railways, very satisfyingly reminds us all that the new needn't always be completely new, that the existing can be relevant and meaningful, that integrating the existing into the new can often be the better option.

One which tends to confirm that any given point in (hi)story is defined by numerous technical and social concepts competing for supremacy, and to question if validity isn't what they should preferentially be seeking. To force one to question, as New Normals did, how such new normals replace the old normals.

One which tends to imply that if left to engineers and their ilk alone the future of rail transport will be a continuation of the need for speed that defined the path of railways through the 19th and 20th centuries. And which thus enables, forces, you to question if we still need that? Do we need the 500km/h the Japanese railway are aiming for, or the 1000 km/h Elon Musk is very keen to achieve? Is that necessary? Is that worth the financial investments and resource usage, is that worth the construction of vast networks of vacuum tunnels and elevated magnetic tracks? What volume of rare-earth elements does that require? How many ecosystems must we destroy? Or is our current 300 km/h on conventional rails, via renewable energy, enough? Who benefits from ever greater rail speeds? As a global society is ever more speed a good thing, or a distraction? Do we not all need to slow down? Are, in comparison to the 1820s and 1920s, other things not more important in the 2020s than ever greater speeds? Are we going to leave decisions on railways to engineers and their ilk alone?

One which doesn't seek to venture inside train carriages, one that is focussed, as the term Futurails eloquently confirms, on the fortschaffenden Mechanik and not the fortschaffenden Erlebnis4, the Transportation Experience of that book Joseph von Baader didn't write simply because it wasn't important in the 1820s; if a subject we'd argue in the 2020s is equally as important as the transportation mechanics discussed in Futurails, arguably more so in context of the question of the influence of society on railways, on the relevance of railways for contemporary society, on the place and purpose and pertinence of railways. What do we want from our trains and railways beyond the transportation they've proved they can deliver? And thus a subject to which we shall return. Similarly we shall return to the unmentioned, but very important and most informative, railway station, past, present and future.

But for all as a showcase Futurails tends help you to place the Wege and Irrwege — paths and wrong/wandering/mistaken/false paths — of the exhibition title in a fresh perspective, to consider Wege and Irrwege afresh. And for which reason we've stuck with the German title here rather than using the official English title Innovation and Aberration on the Track, as, for us, Innovation and Aberration lack something of the instructive of Wege and Irrwege, their use in the title tending to imply that innovation is explicitly good and aberration is always bad. But that's not what Futurails teaches us; rather on the one hand it allows one to approach a better appreciation of Irrwege as being very often Wege that once were impossible, impractical or unacceptable, but which changing technical realities, economic relationships and/or social and cultural positions mean become feasible and possible and, sometimes, desirable, and on the other hand admonishes that Wege that have long been held for correct, ideal even, often prove over time to have in fact been very obvious Irrwege, and therefore the counsel that one should always be open to critically questioning the Wege one is on. And that is being proposed. And thereby Futurails helps elucidate the complexity of society, the complexity of the decisions any society has to make; and that society is not, and never has been, a question of right and wrong, black and white, but about a discourse in ever new contexts and realities with no best answer, and therefore the need for honesty at every stage.

Which is a not irrelevant consideration as we move ever further into the 21st century.

And certainly a not irrelevant consideration as we consider our mobility into the 22nd century, safe in the knowledge that that mobility will to a large extent define society...........

Futurails. Wege und Irrwege auf Schienen is scheduled to run at the DB Museum, Lessingstraße 6, 90443 Nürnberg until Monday December 4th

Full details can be found at https://dbmuseum.de/futurails (regrettably in German only)

In addition a, similarly German only, catalogue is available.

1Clearly only applies where large scale railway networks exist, which isn't everywhere, but for reasons of readability were pretending at this junction it is. Apologies.......

2Joseph von Baader, Neues System der fortschaffenden Mechanik, München, 1822 page 204-205

3Again, in those place with extensive rail networks, which isn't everywhere.

4Awful German, Entschuldigung!!! But you can see why we did it. And why it was necessary. Despite being awful.