In 1922 the Swiss artist and designer Sophie Taeuber-Arp opined that, 'in our complicated times, where the struggle for existence is so difficult, I have often asked myself why we continue to produce embroideries; Why invent ornament and colour combinations when there are so many more practical and, above all, necessary things to do?'1

A question that forces you to question why 100 years later we are still producing not only embroideries but all forms of textile art?

Are our times, perhaps, less complicated?

With the exhibition Textile Manifestos - From Bauhaus to Soft Sculpture the Museum für Gestaltung, Zürich, explore the development of textile art since those 1920s and in doing so allow one to approach such, and similar, questions.......

Textiles count amongst the oldest of human society's objects of daily use; and weaving amongst the oldest production processes developed by human society to manage and define the production of our objects of daily use. A weaving that is not only universal, but in the independence with which it arose in different global regions and cultural contexts tends to be indicative of something that humans have an innate comprehension of and affinity with. Tends to be indicative of a process we universally inherently understand. Much as a Sophie Taeuber-Arp argues that, in terms of textiles, "der Trieb, die Gegenstände, die wir besitzen, zu verschönern, ist ein tiefer und ursprünglicher", 'the instinct to beautify the objects we own is a deep and primal one', a statement that implies a relationship with 'ornament and colour combinations' as innate and universal as with weaving.

And a weaving that while ever present through the coarse of the timeline of Textile Manifestos - From Bauhaus to Soft Sculpture's exploration, has not only taken on ever new expressions over that timeline but has continually been joined by, augmented by, alternative approaches to working with textiles.

A timeline that, contrary to the exhibition title, flows through the central aisle of the Museum für Gestaltung's temporary exhibition space not from Bauhaus, but towards Bauhaus; or perhaps more accurately flows through the central aisle towards the 1920s from the 2020s.

A century of textile art surveyed in the company of a wide range of artists with an equally wide range of materials and approaches including, for example, and amongst many others, Ulrike Kessel whose Nylons in Space from 2025 is literally nylons in space, is Nylon tights, in a profusion of colours, stretched and spun in Space to create a web of metaphor and inquiry; Elsi Giauque and Käthi Wenger whose late 1960s work Theater - Hommage à Dürrenmatt with its application of an active not weaving as a form of weaving deliciously highlights the raw power of doing nothing, the power of late 1960s dropping out of convention, and that also in its plays of colours, forms and perspectives very much reminds of a Xanti Schawinsky's (more or less) contemporaneous spray paint on gauze and canvas compositions as seen in Play, Life, Illusion. Xanti Schawinsky at Kunsthalle, Bielefeld, thereby allowing an alternative perspective on how the plays of colour and form so common in 1920s & 30s institutions such as the Bauhauses moved through and with the 20th century. Or Maria Geroe-Tobler and Ursula Böhmer-Bächler whose early 1950s tapestry Odysseus II not only harks back to the origins of textile art in its form and structure but also in its content: not just in its depiction of characters from Homer's Odyssey, a use of mythology and antique culture as the basis for contemporary art that, arguably, can be traced back to the Middle Ages, but specifically the inclusion of Penelope, wife of Odysseus, at her weaving loom, a loom that plays a key role in Penelope's contribution to Homer's tale and stands as a confirmation of how long we've been weaving, how long we've been creating textile art.

A century of textile art that ends with a large display of works from the 1920s and 30s that unless we missed it, which is always very possible, although we did look incredibly hard, several times, so we don't believe we did, doesn't include a list of the responsible creatives; are, works, if one so will presented anonymously. Which they may well also be. Whereby one hopes not. One hopes we missed the sign.

But a presentation at the end/start of Textile Manifestos' timeline that also features a joint work by Anni Albers and Gunta Stölzl from 1927, a glorious achromatic play on graphic motifs, a delicious use of pattern to create colour; and a joint work that, very poetically, is placed in the centre of the 1920s and 30s, thus where Albers and Stölzl, in their own independent ways, are very much to be located.

Having provided a succinct, but expansive, overview, of the development of textile art in its various expressions over the century of its exploration, Textile Manifestos moves on to a series of equally succinct, but expansive, thematic chapters including foci on, for example, Working Hand in Hand, that collective working that, in many regards, separates textiles from other creative genres; that while in most other genres collective working must be actively structured and sought after, with textiles it's often a natural process, the more natural process. A Working Hand in Hand elucidated via works by, for example, the Bakuba people from the, contemporary, Democratic Republic of the Congo, by the Wari from the, contemporary, Peru, or by a collection of late 19th century quilts created in the, contemporary, USA.

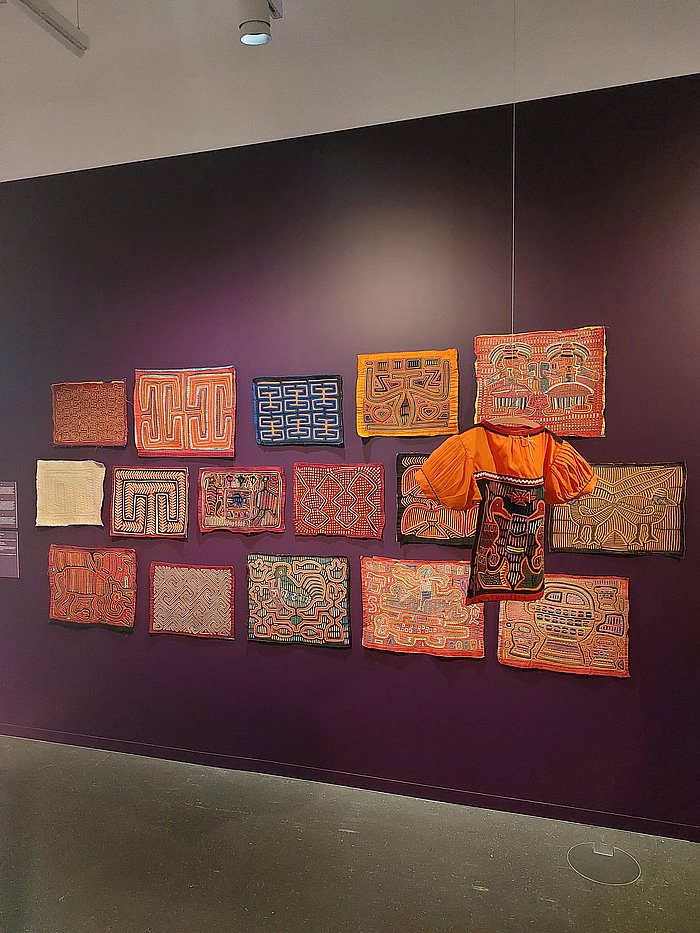

And a collectivity also readable in the textiles by the Guna from the Guna Yala archipelgo in, contemporary, Panama as featured in the chapter Spectral Nuances, a chapter with a focus on textiles where the prominent use of colour and geometry, the use of a wide, often contrasting, contradictory, spectrum of colours and forms, creates results that you don't necessarily have to like, but can't ignore, including, in addition to the vibrant, vital textiles of the Guna, works by Moik Schiele, Isabella Kurfürst or an anonymous 19th century rug originating in Bessarabien, the contemporary Moldova/south-west Ukraine.

A spectral character, albeit less in context of spectral colour as in a spectral etherealness, ghostliness that, arguably, can also be applied to those works on display in the chapter Concentrates by students from Gunta Stölzl's class at Bauhaus Dessau containing cellophane in the weave; a use of cellophane that, as noted by and from Otti Berger. Weaving for Modernist Architecture at the Temporary Bauhaus-Archiv, Berlin, was very much part of the exploration of novel approaches and materials of the 1920s and 30s, and that, for all, is highly indicative of the burgeoning chemicals industry in the early decades of the 20th century and its important influence on, and role in, the developments of the period. See also Bakelite and its relatives.

And see also the great many novel materials as featured in Futures. Material and Design of Tomorrow at Grassi Museum für Angewandte Kunst, Leipzig, that will, should, could, influence coming developments.

Cellophane that can also be considered a component of the discussion in the chapter Sense of Touch, a title that concerns itself as much with a sensuous tactility as with a sensual tactility, the latter form being, perhaps, most graphically illustrated by the soughing and suspiration of satisfaction that reverb through the Museum für Gewerbe's temporary exhibition space from Talaya Schmid's installation Sigh Song. Or perhaps they are a consequence of the sensuous satisfaction of the slippers that also populate the installation. Possibly. (But unlikely.)

Or the chapter Show your True Colours, a chapter in which the question as to in how far Susi Berger is/was patriotically showing her colours with her 1985 Schweizer Stuhl with its incorporation of the Swiss flag in the design, its use of the Swiss flag as the basis for the design, or in how far she was emotionlessly fulfilling a commission for a Swiss Furniture Industry Association keen to show theirs, is very much open; less so the question as to the joy of the object itself. A work that, essentially, is a picnic rug that folds to a chair and back to a picnic rug, and which if it could be, which we sadly don't think it can be, but if it could be folded into a readily transportable quadrat, would a truly remarkable object. But as it is, is an object that stimulates a soughing and suspiration of satisfaction; is an object everyone should be familiar with. But which only the fewest will be.

A demand, a necessity, for familiarity that can be argued for in context of the greater many of the objects on display; thus making the opportunity to become familiar with works you invariably aren't, and that you only very rarely get the chance to explore close up, one of many arguments in Textile Manifestos' favour.

Juxtaposing named creatives of greater or lesser popular fame with anonymous creatives and vernacular practice from across a timespan much greater than that of its central timeline, and setting works from differing periods, different epochs, in dialogue with one another, with the myriad themes, and with its wider exploration, in a presentation in which the various chapters... weave... sorry!!!.... effortlessly to a coherent composition, Textile Manifestos offers pleasingly diverse and differentiated perspectives on and approaches to textile art, and for all on the development of textile art over the century under discussion.

A discussion where as you move ever further backwards from the 2020s, not just in the central aisle timeline but also in the thematic chapters, the works get increasingly more reserved in their expression; but, inarguably, no less experimental or avant-garde. A contrast that allows for reflections on the developments in not just materials and technology over time that influence and inform creative practice, that separate the works at the two ends of the timeline, but also the changes in society, politics, economics, et al, and the mass of collective and individual experience garnered over time, that also influence and inform creative practice, influence and inform what is and isn't possible in creative genres, define what creatives can conceive as possible. Changes that can make a Sophie Taeuber-Arp's focus on beauty in textile art appear a little mono-dimensional.

Or put another way: those in the 1920s couldn't conceive the 2020s, far less the paths still to be taken; but had they been able to, one very much gets the impression from viewing Textile Manifestos, they may very well have produced some very similar works to their 2020s colleagues. A Sophie Taeuber-Arp isn't mono-dimensional, just from an age with an appreciation of, a perception of, an empowerment to work with, fewer dimensions. Much as in a century from now, assuming we make it that far, the positions of today will appear mono-dimensional.

Thus underscoring the importance of not just viewing any given work, but of viewing it in context. And also of appreciating that just because the solutions of the past were appropriate, doesn’t mean they are today, or at least not 1:1, rather of the necessity of continually developing from the solutions of the past solutions appropriate for contemporary realities.

A discussion primarily led by female creatives: if our math is correct the female:male ration is ca. 4:1.2 A state of affairs that on the one hand can be read as an indictment that traditionally textiles have been a female dominion, that over generations, centuries, back to Penelope and beyond, textiles was one of the few creative practices females were allowed to actively engage in; a female dominance in Textile Manifestos that can be read as a confirmation of a male dominance in society forcing females to textiles. Think of the Bauhaus of the title. But on the other hand can be read as Textile Manifestos offering a female centred exploration of the development of a creative practice, allowing females to explain their fundamental contribution to the development of a creative practice, being given a primacy in the development of a creative practice, a primacy in textile art that, arguably, women have enjoyed over the century under discussion. If, potentially, certainly in individual cases, by necessity rather than choice. Can be read as an honest viewing of the archives. Rather than, as so often happens, men being given a primacy in those developments because patriarchal convention assumes they must have had one. They are after all men. And that is confirmed via a formalised, unquestioning, lazy, viewing of the archives.

You can take your pick as to how you assess the female dominance. Or perhaps more instructively, view it as both and let the two positions engage with one another as a component of wider reflections on the popular narrative of creative (hi)story, of creative (his)tory.

Men are however present in Textile Manifestos, as they unquestionably are in the (hi)story of textile art, including, whether by accident, a skewing through Groupthink, or a reflection of a genuine dominance over the decades, a great many Japanese creatives including, for example, Shigeki Fukumoto, Masao Yoshimura or Masakazu Kobayashi, the later whom as the curators note collaborated with his wife Naomi, albeit without those same curators including Naomi as one of the represented creatives in her own right, unlike Masakazu, thus neatly illustrating one of the processes via which female creatives become anonymous when they cooperate with their husbands: institutional Hudelei. But also featuring non-Japanese male creatives such as, for example, Sweden's Claes Oldenburg, Hungary's Victor Vasarely or Switzerland's own Johannes Itten, who for all he is most popularly associated with the Vorkurs at Bauhaus Weimar, and the troubling popularity of the Mazdaznan cult at Bauhaus Weimar, was also co-responsible for the setting-up and earliest years of the weaving workshop at Bauhaus Weimar.

While the echos of the aforementioned anonymous 19th century Bessarabien rug in Itten's rug from 1920, a rug in all probability realised in that Weimar workshop, allude not only to the important influence of Slavic and associated eastern European folkloric in the development of 20th century Expressionism, but also that for all the Bauhauses are popularly held up as being something revolutionary, they were, as everything is, but a component of a path that started long before them.

Men and women whose Manifestos of the title, as one increasingly appreciates in the course of viewing them, through engaging with them, aren't the programmes, be that political or artistic, cultural, that is the primary definition of manifesto, but rather are positions, are arguments, on how the individual life should be led, and how a cohesive, responsive society can be woven from those individual lives.

In which context Textile Manifestos' chapter Social Fabric, we'll argue, is superfluous: the whole presentation is concerned with the social fabric, and how since the 1920s creatives have both responded to the realities of the contemporary social fabric and made proposals as to how to fortify and tweak that social fabric. Albeit not in manner that is about asserting your world view, but rather about putting your views up for discussion and seeing where that discussion goes. That thing that as a global shouty-social-media society where everyone has a definitive answer, everyone knows exactly what to do, we're getting ever worse at. But which Textile Manifestos encourages us all to re-learn.

And a collection of positions on the social fabric since the 1920s that makes Textile Manifestos as much a journey through a century of human society as a journey through the textiles, the textile art, of that century. A journey through the social fabric as much as through the fabrics of society.

A journey from the complexities of the 1920s to the complexities of the 2020s where the further development of the existing in new contexts inherent in the works on show echos in the manner which the fundamental questions of society of the 2020s are, in many regards, the same as those of the 1920s just in new contexts and thus similarly requiring new approaches to their answering; where the number of repeating positions, repeating demands and desires, repeating challenges throughout the century implies how little society has moved on in that century for all that the two ends of the timeline are thoroughly unrecognisable from each other. Much as the art on show is essentially the same at both ends of the timeline, but fundamentally very different.

A journey that underscores not only the important role textiles play in human society but the important role art plays in human society; an art that, as oft discussed in these dispatches, and as Textile Manifestos tends to reinforce, is in itself passive, doesn't have active agency as design and architecture do, rather can but stimulate, challenge, admonish, validate the viewer, demand action from the viewer. Something, as, again, Textile Manifestos tends to reinforce, that is as important as providing the appropriate means for that action.

A journey that helps elucidate that the close connections between textiles and society aren't just in context of the practical but also in context of the conceptual; that human society's 'deep and primal' instincts in context of textiles aren't just material but also immaterial. Or as Sophie Taeuber-Arp opines 'I don't believe that this instinct to beautify objects is a materialistic one, identical only with the desire to possess and increase its value through beautification', rather for Taeuber-Arp the innate, universal instinct to create beautiful things is related to a "Streben nach Vollkommenheit", a 'striving for perfection'. A 'perfection' whose definition is and was very much open, very much up for discussion, but which, inarguably, regardless of your definition, corresponds to achieving a desirable fortification and tweaking of the social fabric in context of contemporary realities with an eye on an unknowable future.

Textile art in itself will never allow us to reach that perfection, it's passive, but in its discourse with society, and in its discourse with design and architecture, is an important and powerful tool in helping us to better formulate the necessary questions and to discuss the myriad proposals that arise from those questions. A position, in many regards, also advanced by Sophie Taeuber-Arp in her answer to the question 'why we continue to produce embroideries?': not for the embroideries themselves but for the manner in which creating and producing embroideries allows one to approach other questions, including questions of contemporary society. Embroidery as a proxy, as a tool. Art as a conduit and platform for discussion. Which also reinforces that Taeuber-Arp was anything but mono-dimensional: that when she was talking of beauty, she also wasn't.

And thereby a journey, an exhibition, that allows one to identify a fallacy in Taeuber-Arp's formulation of her question as to 'why we continue to produce embroideries?: there are, without question, more practical things that need doing than inventing 'ornament and colour combinations', always were, always will be; but, as Textile Manifestos allows one to better appreciate, in terms of enabling textiles to be the active material and immaterial component of human society they always have been, in terms of granting textiles their inherent agency beyond the practical, in terms of the important physical and conceptual roles textiles play in human society, in terms of the power of art as a platform for reflection and a tool for the fortification and tweaking of the social fabric, there is little that is more necessary.

For if we stop inventing 'ornament and colour combinations', if we stop creating textile art, stop embroidering, that implies we've stopped developing as a society.

And in 'complicated times' that would be fatal.

Textile Manifestos - From Bauhaus to Soft Sculpture is scheduled to run at the Museum für Gestaltung, Ausstellungsstrasse 60, 8005 Zurich until Sunday July 13th

Further details can be found at www.museum-gestaltung.ch

1and all other quotes unless stated, Sophie Taeuber-Arp, Bemerkungen über den Unterricht im ornamentalen Entwerfen, Korrespondenzblatt des Schweiz. Vereins der Gewerbe- und Hauswirtschaftslehrerinnen, Vol 14, Nr. 11/12, December 1922

2As far as we can ascertain all represented creatives identify as/are identified as male or female, but that may not be the case. And while such a binary world view is one the many things that have changed since the 1920s, at least in public discourse arguably not in private struggles, for the sake of readability we stick with a female:male division while happily accepting it ain't that simple. And also not commenting on other factors that we probably should comment on, such as the whiteness of the represented creatives.......