There is currently a lot of "buzz" in the contemporary furniture and interior design communities about bringing nature in to domestic spaces, of finding ways of integrating plants with furniture and furnishings, softening our harsh, uncaring modern world if you will.

In recent months we have posted, for example, on Stephan Schulz's Domestic Landscape project, Green Lamp by Zuzanna Malinowska or Werner Aisslinger's Bikini Island concept for Moroso.

While at the recent Designers' Open Leipzig there were numerous examples of such concepts, projects ranging from the truly, unacceptably, hideous to the unashamedly ingenious.

All of which kept and keeps bringing us back to one of the earliest objects that aimed at combining plants and furniture in domestic harmony, an object that combined such with further, intelligent, features, an object so perfectly suited to the job and so thoughtfully crafted, you wonder why anyone else need tackle the subject.

And an object which is predictably no longer available.

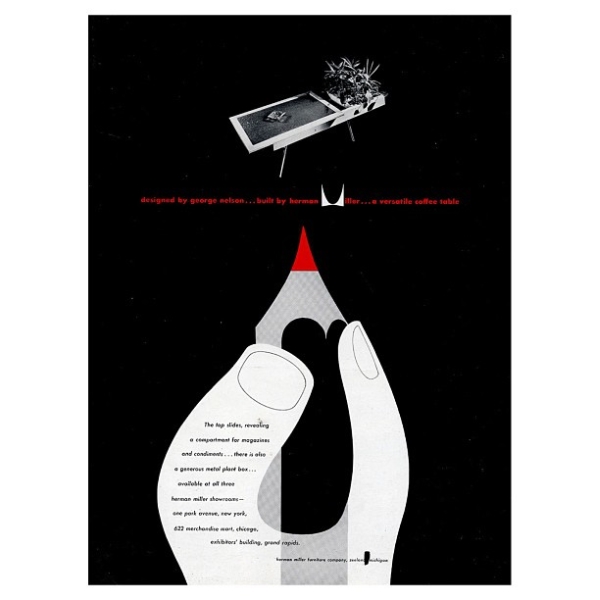

Launched in 1946 as part of George Nelson's inaugural furniture collection for leading American designer furniture manufacturer Herman Miller, "Coffee Table 4662" is/was created from birch and combines a copper plant pot holder next to a general storage space hidden below a slideable tabletop, and all presented in an object that is as charmingly formed as it is exquisitely proportioned.

In addition to its sublime beauty what makes Coffee Table 4662 so rare and fascinating is that, and as far as our research allows, it is probably one of the few pieces of furniture that was actually, genuinely designed by George Nelson.

For despite spending over two decades as Chief Designer at Herman Miller, and having a defining influence on the development of mid-20th century American design, George Nelson designed only very, very little of the furniture associated with him.

The Tray Table is by Ernest Farmer.

The Pretzel Chair is by John Pile.

The Coconut Chair is by George Mulhauser.

The Marshmallow Sofa is by Irving Harper.

The Nelson Bench is by..... George Nelson.

That George Nelson didn't design all of his furniture is and was no secret.

But then George Nelson was never really a designer in the biblical sense. Nor was George Nelson hired by Herman Miller as a designer. He was hired to lead the Herman Miller design department, to lay down the creative direction, to bring a contemporary, modern accent to the company's portfolio, and for all to ensure that Herman Miller became and remained a commercial success.

That he achieved these goals with such an apparent ease was unquestionably down to his understanding of the mood of the era and his long deliberations on the nature and meaning of "design".

Although trained and occasionally engaged as an architect, George Nelson first made a name for himself as an author and journalist. An author and journalist specialising, somewhat logically, in architecture and related subjects.

In 1945 he and his colleague Henry Wright published "Tomorrow's House", a sort of advice book on modern building, interior design and domestic technology. Included in "Tomorrow's House" was Nelson's concept of the "Storage Wall", a modern, modular alternative to the heavy, solid storage cabinets and wardrobes of the period.

Largely a theoretical argument rather than a piece of product design per se, Storage Wall caught the attention of Herman Miller CEO D.J. De Pree.

Following the untimely death of Gilbert Rohde Herman Miller were actively searching for a new Chief Designer, and through Storage Wall, or better put, through the thinking behind the idea that led to Storage Wall, D.J. De Pree saw potential in George Nelson. Potential that was confirmed by a first meeting between the pair in November 1944; "He has a splendid background", De Pree wrote to the company's then Sales Director Jim Eppinger, "is thinking well ahead of the parade; does not want to be limited to the use of wood in planning furniture..." And following further meetings in February 1945, "His thinking and approach is the very thing we want" and noted that Nelson was "....actively working on the things that will make for better living"

However despite the very positive nature of the meetings Nelson's biographer Stanley Abercrombie states that George Nelson was "... frank about his lack of experience in furniture design and not eager to rush into an agreement"

Eventually however George Nelson and Herman Miller did reach agreement and it is a tribute to the character of the the man that one of George Nelson's first actions was to take himself off on a tour of American furniture producers, to get a feel for and understanding of the furniture industry of the day.

An industry that until then he knew next to nothing about.

What he learned from his tour can be gleaned by the speed with which he subsequently brought Isamu Noguchi and Charles Eames into the Herman Miller fold. Something for which we think everyone can be very grateful.

George Nelson himself however remained largely a theorist and observer rather than a hands on creator, or as Irving Harper, a designer who collaborated with George Nelson for over 25 years, told Julie Lasky, deputy editor of the New York Times’ Home section, "I never saw George sit down and design anything."

Similarly, in the introduction to his Nelson biography Stanley Abercrombie recalls working with Nelson on an installation for the lobby of the Herman Miller HQ, and for all that during the numerous project meetings Nelson would "... describe his vision for the design, never lifting a pencil. I would leave, attempt to put on paper some semblance of what I thought he meant, and return with my sketches. Sometimes Nelson would find them hopelessly foreign to what he had pictured; sometimes they would be acceptable; but even when right on target, they served mainly to provoke him into thinking of other possibilities"

A similar process can be found in the creation of George Nelson's first furniture collection for Herman Miller. The collection was created in very close cooperation with the young German designer Ernest Farmer, who, according to Stanley Abercrombie, "... would report daily to Nelson's office in the Empire State Building to discuss Nelson's ideas, and every night he would revise the drawings as Nelson wanted".

Note: "revise the drawings as Nelson wanted". Not "revise Nelson's drawings ...."

Consequently while it is fair to say that George Nelson was unquestionably responsible for the general concept behind and direction of the programme, the majority of the collection carries much more Ernest Farmer's formal signature than George Nelson's. Or indeed at times more Charles Eames and Eero Saarinen than Ernest Farmer and George Nelson. A central component of the collection was a modular shelving/storage system, officially credited to Farmer but which owes more than a casual passing nod to the Case Furniture by Eero Saarinen and Charles Eames that won the 1940 MoMa New York "Organic Design in Home Furnishings” competition.

However certain objects, including the aforementioned Nelson Bench, the Extension Coffee Table and Coffee Table 4662 do, thankfully, appear to be the work of George Nelson. An indication that occasionally, possibly when he alone, he did design things.

The decision to credit all works to George Nelson regardless of who had the lead was not one taken on account of any particular egoistic trait in George Nelson's character. We never met the man but those who did describe him as anything but vain and self-important. And indeed in a 1957 essay he discusses contemporary design and for all compares the nature of the design process then with now. " In former times" he writes, "the "designer" was not an individual, rather a complex social process of trying, selecting, disposing. Today it is very much the same, just of a different type, yet today we tend to over value the importance of the individual"

However, and despite George Nelson's personal feelings, he was working in the first bloom of a marketing led, branded world and so regardless who was lead designer on a project the decision was that only one designer would be named as the creative force. And that one should, logically, be George Nelson.

A situation that is very much the same today.

Most contemporary furniture designs attributed to a single designer are in reality the result of a collaborative effort from a "studio", the amount of input from the named designer varying from project to project, studio to studio.

George Nelson just being in that sense, once again, somewhat "ahead of the parade"

And just as George Nelson was very particular about naming and crediting all involved when projects were profiled in trade magazines, so to do designers such as Stefan Diez or Konstantin Grcic name all involved creatives on their websites.

That the manufacturers don't list all individuals involved in a given project is understandable and, ultimately, probably fair enough.

Just as it was that back in the day when Herman Miller credited George Nelson alone.

What is however neither fair nor understandable is that we should be denied an object such as Coffee Table 4662.

Not least because it offers a rare insight into George Nelson's personal design signature......