There are few more unpleasant emotions than the one deep in your stomach when you realise your bicycle has been stolen. An unpleasantness caused less by the financial and time investments involved in organising a replacement, than on account of the bond that exists between you and your (ex-)bicycle.

A sense of why and how such an emotional bond comes to be formed with an otherwise unemotional object, can currently be found in the exhibition Self-Propelled. Or how the bicycle moves us, at the Kunstgewerbemuseum Dresden

Curated by the design journalist and consultant Petra Schmidt Self-Propelled is partly inspired by the imminent two hundredth anniversary of Karl Drais's 1817 Draisine "Laufmaschine" - Running Machine - and thus, in effect two hundred years of the bicycle, partly by the contemporary relevance of the bicycle, but for all by Schloss Pillnitz, the Baroque residence on the banks of the River Elbe, slightly outwith Dresden, and which today houses the Kunstgewerbemuseum, "Schloss Pillnitz was a summer residence and the Kunstgewerbemuseum is only open in the summer months, thus we wanted an exhibition which related to both summer and also the journey here, so the route, the distance, from Dresden to the Schloss, and one which in addition motivated people to make that journey", explains Petra Schmidt the background to the exhibition.

Bicycles offered just that subject.

Formally split into five sections looking at how the bicycle moves us mechanically, socially, physically, emotionally and how it may/will move us in the future, Self-Propelled is also a chronological tour through two centuries of bicycle design and cycling history; a tour which amongst other things very nicely illustrates that in their preference for fixed wheel bicycles the contemporary urban hipster is no more advanced than your average 19th century toff. A newly acquired piece of wisdom for us, and one which promises to make our next visit to Berlin all the more enjoyable.

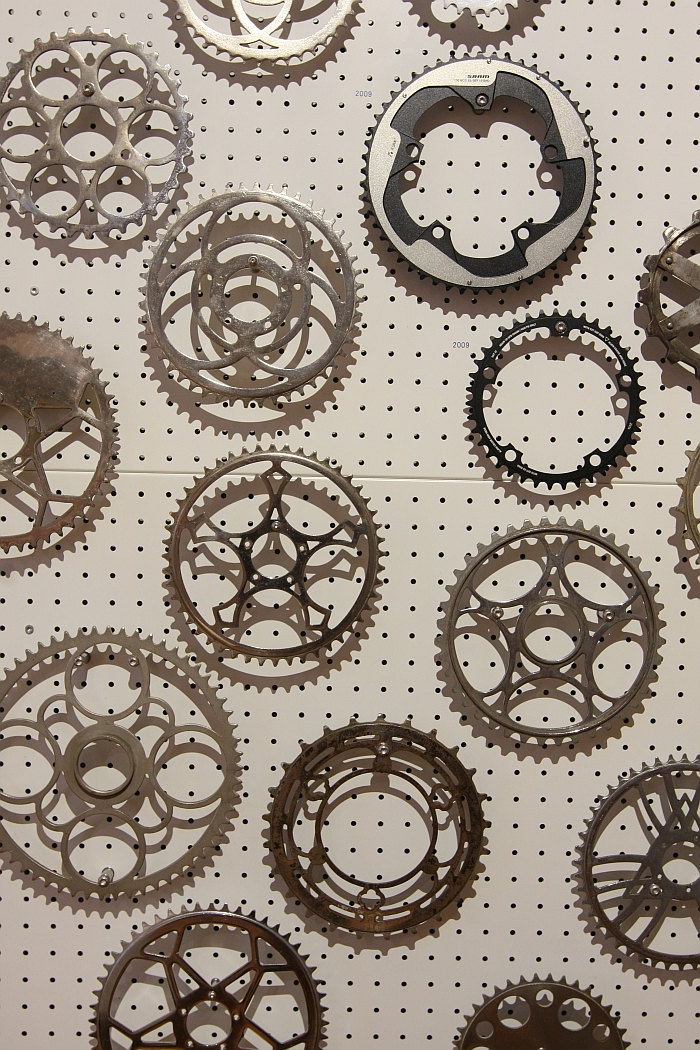

In addition to presenting a wide selection of bicycle designs Self-Propelled also documents the development of bicycle components such as wheels, lights, chain rings and selected items of clothing, including a very pleasing reacquaintance with David Gebka and Freia Achenbach’s Wind Jacket as recently seen in Milan as part of the ABK Stuttgart's Più di Pegoretti project, a project which is included in Self-Propelled in an abridged form*, and sadly without the monolithic Bike Stand by Marvin Unge, an object which in our opinion really should have been included, fitting perfectly as it does to the Baroque ambience of Schloss Pillnitz.

Necessarily brief on account of the limitations of space, the inclusion of those technical components from which a bicycle is constructed nonetheless rescues the bicycle from the overly graphic, almost cartoon, context in which it is often understood these days and makes very clear it is an industrial object, a functional object. And that Self-Propelled is a design exhibition. Not a celebration of the bicycle for the sake of celebrating the bicycle or as part of a perceived culture, but an exhibition about a formal and functional evolution, about new applications of materials, about new solutions to age old problems. About design. And about how design influences society, and society influences design. The bicycle being the conduit, and a culturally relevant and historically important one at that.

Although officially one of the five sections the social relevance of the bicycle is in many ways the secret main theme of the exhibition, one that touches in some way on all the other four, be that, for example, in terms of the changes in transportation and thus social changes the mechanical development of the bicycle made possible; the question of how healthy society's relationship with sports idols is, as highlighted by Tim Kölln's portraits of, lets say "normal", journeyman, professional cyclists and the not that physically far removed image of Lance Armstrong; the way the emotional bonds that exist between one individual and their bicycle are often shared with others and thus leads to friendships across (apparent) boundaries; or how the application of new technologies in cycling can and will affect future society.

For curator Petra Schmidt the social relevance of the bicycle come down to the question of who cycles and why,"Bicycles have always been part of counter culture, the autonomy that a bicycle allows helping individuals to re-think their position in the world.", she explains , "for example, in respect of women, with the bicycle came a new independence, the chance to escape the previous domesticity, and thus a new perspective, and which also led to changes in fashion, changes not caused through the bicycle alone but to which cycling contributed. Similarly with the workers' movements, the availability of bicycles meant workers could, for example, go on group tours and so thus develop and strengthen a sense of community, a collective spirit."

But was cycling always so democratic?

"No, not all", answers Petra Schmidt, "in the early days hardly anyone could afford a bicycle it was only something for the rich, the Draisine, for example, was known as the Dandy Horse, which gives an idea of the type of extrovert who possessed one, but then around 1890 the bicycle became a mass produced, industrial, product, and thus became affordable for a much wider range of individuals."

And having become affordable, quickly established itself and became not only the multi-faceted and universal object it is today, but an object with which we all associate a sense of freedom, independence, and for all the chance to express ourselves, be that in terms of hanging with friends down at the local BMX park, showboating through town, optimising your physical condition, going to school or escaping the strain of modern urban life to spend time alone in the countryside. There are reasons why the scene in the film Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid in which Butch shows of his new bicycle is so endearing: aside from the obvious allure of trying to steal your best friend's girl, the spirit of release and freedom so obviously enjoyed by Butch and Etta is something we can all relate to, and knowing that they are experiencing such for the first time makes you very happy for them.

We think we move the bicycle, the bicycle moves us.

Viewing Self-Propelled makes it very clear that despite the changes and evolution the bicycle has undergone since 1817 it has remained, essentially, the same, or as Petra Schmidt phrases it "By 1900 the bicycle as an object existed in its final form." And while, yes, in our modern wireless networked world there are new options as to how one uses and interacts with a bicycle, and indeed how cyclists interact with one another, such technology has had, and will only have, a very limited effect on the actual bicycle itself. What may/will have a greater effect is the rise of the electric bicycle, the so-called Pedelec; the addition of the motor fundamentally altering the action of cycling for the first time since the invention of the so-called "safety bicycle" in the 1880s saw a chain drive the rear wheel.

Does however the Pedelec mean the end of the bicycle as we know it?

"The Pedelec is a hybrid and this "motorisation" of the bicycle, does the bicycle good because it opens up new possibilities", answers Petra Schmidt, "for example, the idea of bicycle superhighways, a concept which is becoming increasingly common, is very closely connected with the development of Pedelecs because they offer the possibility that a wider mass of people can cover much longer distances by bicycle than was previously the case, and that then opens up whole new worlds of possibilities"

And thus ensures that the bicycle will continue to accompany society, reflect society and, and remaining with the exhibition title, move society, for a few years yet.

Thankfully avoiding all the lifestyle/typography/graphic design "porn" that is popularly confused with cycling, Self-Propelled is a very accessible, self-explanatory exhibition which places the focus on the bicycle as an object of universal, daily use, and in doing so provides a fulsome introduction to the (hi)story of cycling and bicycle design. If for us it is an exhibition with one, small, omission.... an exploration of the historic development of the bicycle lock. For there are few more unpleasant emotions than the one deep in your stomach when you realise your bicycle has been stolen.

Self-Propelled. Or how the bicycle moves us runs at the Kunstgewerbemuseum, Schloss Pillnitz, Wasserpalais, August-Böckstiegel-Straße 2, 01326 Dresden until Tuesday November 1st, and is bi-lingual German/English. And for all planning taking up Petra Schmidt's invitation to cycle to Schloss Pillnitz, the Schloßfähre ferry acrross the Elbe costs for cyclist + bike €3,50 return. Yes, you could go the long way round and avoid the use of the ferry. It is also a nice route, but does mean no ferry........

Full details on Self-Propelled, including information on the accompanying fringe programme, can be found at: www.der-eigene-antrieb.de/