That joining the Women's Department weaving workshop was for many a female Bauhäusler not so much an active wish as the response to a take-it-or-leave-it proposition, shouldn't be confused with the workshop producing work of an involuntary, unloving, uncaring nature, of it playing second fiddle to the rest of the institution. Far from it. The quality and relevance of the work created in the Bauhaus weaving workshop being in many regards attested by the fact it was one of the more productive and commercially successful Bauhaus workshops.

With the exhibition Bauhaus. Textiles and Graphics the Kunstsammlungen Chemnitz explore the work undertaken in the Bauhaus weaving workshops, some of the institutions' principle protagonists and their place in wider considerations of inter-War weaving. While also neatly, if indirectly, highlighting Bauhaus's gender differences, inequalities, prejudices......

"Are woven fabrics something that should be a task for the creative will of mankind?", asked Gunta Stölzl, the (future) head of the Bauhaus Dessau Weaving Workshop in 1926.

"Yes!" her emphatic reply, for, "woven fabric is an aesthetic whole, a composition of form, colour and material in unity"1

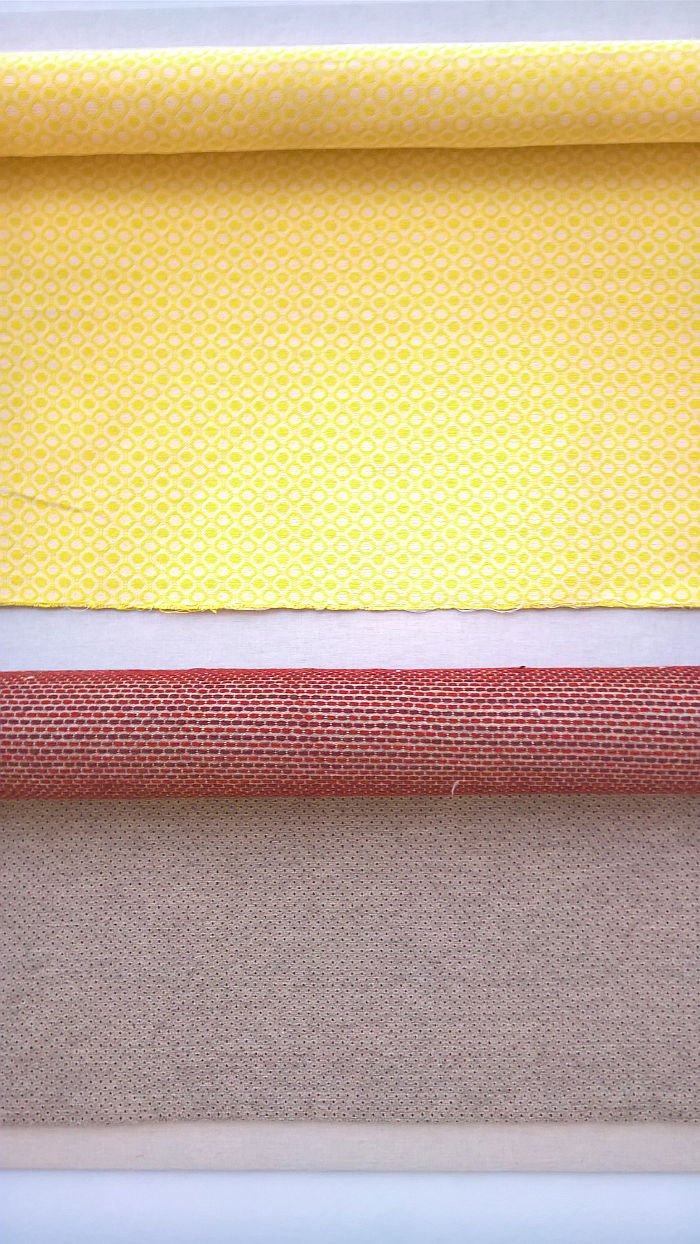

On a basic level, if you will, as a plain weave, Bauhaus. Textiles and Graphics explores how that understanding of the unifying interplay of form, colour and material was expressed and developed at Bauhauses Weimar and Dessau, both through works by Bauhäusler such as, and amongst numerous others, Ida Kerkovius, Otti Berger or Benita Koch-Otte and also through the wide range of textiles produced in the Bauhaus weaving workshops, a range once surmised by Stölzl as encompassing four categories: blankets/curtains, rugs, furniture fabric and gobelins/wall hangings.2 And which in doing so helps explain in much more detail, as a, figurative, inlay weave, the processes and conceptual thinking that underlies much of the work; that far from being simply patterns, simply textiles, works such as those on show in Chemnitz represent deliberate, considered artistic acts, acts based on the understanding that a textile, as Gunta Stölzl argues, "is always an object of service", yet objects defined not only by their purpose but also their composition, including the properties of the material, the nature of the weave, the pattern and "the colour, increased or weakened through lustre or dullness"3

And despite the age of the works, the reduced lighting in the Kunstsammlungen's exhibition rooms perfectly underscoring the fragility and temporality of textiles, the colours, lustrous and dull, remain not only prominent, but their intention and function are still very present, can still be explored, questioned, admired and enjoyed. As can the forms, materials, the unity. And thereby helping to remind us on the one hand, how much the works of the inter-War years continue to influence and inform contemporary textile understandings, and on the other hand that one should never forget that although, in many regards, much of what is on show in Chemnitz is for today's eyes thoroughly unremarkable, for its time it represented a minor revolution; something perhaps best expressed through a mid-1920s rag rug by Helene Schmidt-Nonné, and which, quite frankly, you wouldn't be surprised to find on the shelves of a blue and yellow out of town furniture superstore. Alone its price tag might cause you to question its provenance. And a rug whose contemporaneity is deliciously augmented by the fact that it was owned, and we're hoping actively used, by Marianne Brandt, before, and with, as she noted, heavy heart, she sold it in 1976 in context of the health enforced move from her own home into a care home.

Beyond new aesthetic understandings Bauhaus. Textiles and Graphics also takes a brief if regular excursion over the "machine versus hand" weaving debate of the inter-War years, underscoring that while the featured Bauhäusler weren't Luddites taking physical mallets to weaving machines, they weren't averse to swinging a philosophical mallet in defence of hand weaving, a process which was (generally) viewed at Bauhaus as offering not only the more interesting results but also the most faithful representation of the idea and intention from which a textile arose; that they weren't opposed to technological advances per se being alluded to by examples of the use of, experimentation with, new materials, including a piece of fabric produced by the Handweberei Hohenhagen and incorporating Baykogarn, a metallic coated cotton, specifically in this case, a gold coated cotton.

Mention of the Handweberei Hohenhagen confirming that despite the unequivocality of the title Bauhaus. Textiles and Graphics isn't purely Bauhaus but also features works by both institutions and protagonists conceptually linked to Bauhaus, such as Burg Giebichenstein Halle or the Handweberei Hohenhagen, as well as those with whom Bauhaus cooperated and who produced Bauhaus designs, such as Polytex Berlin or Deutsche Werkstätten Dresden; and also follows selected protagonists post-Bauhaus, or perhaps more accurately put, uses examples of their works to highlight aspects of the post-Bauhaus careers of the likes of Else Mögelin in her workshop in Gildenhall near Berlin, or Gunta Stölzl through her Flora weaving shop in Zürich.

Aside from the works themselves a further highlight is the presence on a couple of the pieces of an aluminium Bauhaus signet, which isn't something one sees all too often, and something that was applied as both a guarantor of quality and also as an act of branding, and thereby a conformation that Bauhaus was as much about commercial activities as it was pedagogic; something underscored by the fact that products with the Bauhaus signet weren't attributed to any individual artist, were simply Bauhaus. And a signet which when one considers the creativity for which Bauhaus is famed, is a bit, well, bland, uninspired. If nonetheless interesting.

In addition to textiles Bauhaus. Textiles and Graphics also presents ..... graphics.

And while there is a creative connection between the two, for all the influence that the likes of a Paul Klee or a Wassily Kandinsky had on the colours, patters, forms and alignments of the textile designs and thus the interplay between the Bauhaus 2D and Bauhaus 3D, the main connection is to be found in the silent third part of the exhibition title: Bauhaus. Textiles, Graphics and the Kunstsammlungen Collection. The museum taking advantage of the Bauhaus Weimar centenary for a rare opportunity to present their Bauhaus collection, the exhibition comprising as it does exclusively objects from the Kunstsammlungen collection and thus neatly underscoring the breadth of the institution's Bauhaus collection, or more accurately put Bauhaus & Friends collection.

As with the textile presentation the graphic presentation is divided into works realised in direct context of Bauhaus, including Lyonel Feininger's Cathedral woodcut which featured on the title page of Gropius's 1919 Bauhaus manifesto, and works created either by Bauhäusler post-Bauhaus or by those conceptually allied to and with the school, including works by Willi Baumesiter, Kurt Schwitters, Alexej von Jawlensky and numerous plates from the, from Walter Gropius organised, 1921 publication, New European Graphic Art. Third Portfolio.

But perhaps most importantly, passing from the textiles to the graphics one passes not only from 3D to 2D, but from a female domain to a male domain.

There is one male represented amongst the textiles, Sigmund von Weech, who wasn't a Bauhäusler, but whose works can very much be understood in context of Bauhaus; and there is one female represented amongst the graphics, Jacoba van Heemskerck, who wasn't a Bauhäusler but did feature in the aforementioned, New European Graphic Art. Third Portfolio. Otherwise the near complete gender disparity between the textile presentation and the graphic presentation makes the gender division at Bauhaus unignorable.

Yes, Bauhaus. Textiles and Graphics does feature a mix of works by Bauhäusler/non-Bauhäusler and also works created at Bauhaus/Elsewhere, and thus isn't a "pure" Bauhaus exhibition. And, yes, is also based solely on one institution's collection rather than an academic survey of works produced at Bauhauses Weimar and Dessau. And so yes, one could argue we are taking a few liberties with such a bold statement; but, the clear female/male division between the textile/graphic presentations does reflect, and stand representative of, a reality at Bauhaus.

A reality at Bauhaus where female students were limited to where they could work and what they could undertake; women wove. Or pottered or bound books. And that not just as a result of the attitudes of a Walter "we are fundamentally against the training of female architects" Gropius or an Oskar "where there is wool, there is a woman" Schlemmer, but also the female Bauhäusler themselves. "The artistically working woman", noted Helene Schmidt-Nonné in 1926, "concerns herself primarily and most successfully with surfaces. This is explained by her lack of spatial imagination, something that is peculiar to the man",4 and thereby echoing Gunta Stölzl's opinion that "the play with form and colour, increased material sensibility, strong empathy and adaptability, a more rhythmic than logical thinking, are general features of the female character"5, Stölzl also noting that while "in the early days Bauhausmädchen tried each workshop: carpentry, murals, metal, pottery, bookbinding", it soon became apparent that, "the heavy plane, the hard metal, the painting of walls was for some not the activity that corresponded to their mental and physical strengths."6 Whereby one notes the use of Bauhausmädchen, and as with the Bauhausmädels used in the 1930 magazine article "Mädchen wollen etwas lernen" as presented in Four "Bauhausmädels" at the Angermuseum Erfurt, its use in a dichotomous augmentative/diminutive context, that women can but can't, and in any case prefer not to. Something further underscored by the prominent public position of the Bauhaus weaving workshop, the platform it afforded its members, yet the relative passive acceptance/defence of the patriarchal status quo.

And for us this gender division comes a little short in the presentation. In the accompanying publication the Kunstsammlungen's Director Frédéric Bußmann notes that females were "banished" to the weaving workshop and that the graphics on show in the exhibition are very male, but in the exhibition itself, such isn't explained as fully as it, arguably, could be. Or put another way, when the exhibition notes that in 1927 Gunta Stölzl became the first and only Bauhaus Jungmeisterin, visitors need to instantly understand that it is akin to a woman being ordained and appointed as an assistant Priest in the catholic church.

And while we freely and happily accept that discussing the realities of the gender imparity at Bauhaus is a huge subject, not something that can be quickly explained, or indeed something that should be quickly explained but that it is something deserving of a full, sober analysis; we do feel that if you're presenting Bauhaus, Textiles and Graphics, the gender disparity between the latter two should, must, be part of the discourse on the former.

Beyond textiles and graphics the Kunstsammlungen also manage to shoehorn Chemnitz's own Marianne Brandt into the exhibition, not that we're complaining. All familiar with these dispatches will know the regard in which we hold Marianne Brandt, and while the ten photos presented may have only little to do with the textiles alongside which they hang, other than reminding us that there were women at Bauhaus who didn't weave, that it was possible, if rare, to avoid banishment to the Women's Department, they do provide for a very pleasing introduction to the abstract, technical, experimental, creative thinking of Marianne Brandt. And provide for a nice contra-point to the main focus of the exhibition.

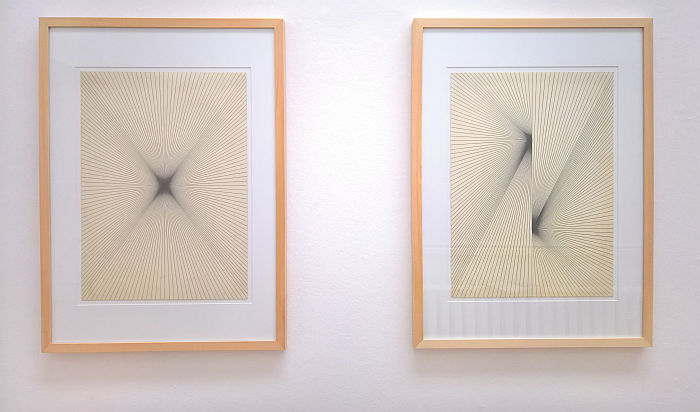

A further contra-point is provided by the parallel, technically abutting, presentation of works by the Sächsiche artist Karl-Heinz Adler; not a Bauhäusler himself, he was born in 1927, but an artist whose work with its forms, colours, geometry and for all its references to and considerations of space, alignment, rhythm can be considered very much informed by developments of the inter-War years. And which thus allows one to return to the textiles and to view them anew, through, if you will, the retrospect eyes of the next generation.

Bijou in terms of items presented but much wider in terms of ideas, ideals and positions, Bauhaus. Textiles and Graphics provides for an engaging, accessible, coherent and informative overview of the Bauhaus weaving workshops, both directly and in their wider context, if one that, for us, doesn't take as deep, as critical, a view of the reality in which the institution existed as it arguably, could, should; however the clues are there, there is enough to allow you to follow up yourself later. Which we'd clearly advise you do. What Bauhaus. Textiles and Graphics does do very well is allow you to approach a better understanding of the nature of the works realised in the Bauhaus weaving workshops, of the relationships entertained by the Bauhaus weaving workshops, of the characters and individuals involved, of the philosophies and understandings from which the work they produced arose, of the quality and relevance of that work. Or put another way, as an exhibition Bauhaus. Textiles and Graphics neatly reflects and embodies Gunta Stölzl's 1931 assertion, "that we are on the correct path is demonstrated by experience: the cultural influence of our work on the textile industry and other textile workshops is today clearly visible"7

And remains so in 2019.

Bauhaus. Textiles and Graphics runs at the Kunstsammlungen Chemnitz, Theaterplatz 1, 09111 Chemnitz until Sunday August 4th

Hommage à Karl-Heinz Adler runs until Sunday August 11th

Full details (German only) can be found at www.kunstsammlungen-chemnitz.de

1Gunta Stölzl Weberei am Bauhaus, Offset, 1926 reprinted in Gunta Stölzl. Weberei am Bauhaus und aus eigener Werkstatt, Bauhaus Archiv, Kupfergraben-Verlag, Berlin 1987

2ibid

3ibid

4Helene Nonné-Schmidt, Das Gebiet der Frau im Bauhaus, Vivos voco, Volume V, Edition 8/9 August/September 1926, reprinted as incomplete extract in Hans Maria Wingler, Das Bauhaus: 1919 - 1933, Weimar, Dessau, Berlin und die Nachfolge in Chicago seit 1937, Rasch Verlag, Bramsche, 1975

5Gunta Stölzl Weberei am Bauhaus, Offset 1926 reprinted in Gunta Stölzl. Weberei am Bauhaus und aus eigener Werkstatt, Bauhaus Archiv, Kupfergraben-Verlag, Berlin 1987

6Gunta Sharon-Stölzl, Die Entwicklung der Bauhausweberei, bauhaus Dessau 5, 1931, reprinted in Form und Zweck, Issue 3, 1979

7ibid

And our tip, plan a little extra time, the lighting is reduced, which isn't a complaint but a necessity, and it takes the eyes a little time to adjust. Once they do, the experience is all the better.