Interesting, important and not irrelevant as hygiene is at the moment, the new exhibition at the Deutsches Hygiene-Museum Dresden doesn't concern itself with pandemics, but with another subject of contemporary global interest, importance and relevance: food, food supply, food security.

And a theme not entirely unrelated to, certainly not unaffected by, our current reality......

Established in 1912 the Deutsches Hygiene-Museum owes its existence to the 1911 International Hygiene Exhibition, an event which sought "to make people aware that health care is the basis of individual well-being and the prosperity of nations, and that it is in everyone's power to contribute to the maintenance and strengthening of their physical and mental well-being"1, a very contemporary message, and which in attempting to mediate such took a very wide view of "hygiene", and thereby, or as best as we can reconstruct a century and a bit after the fact, presented, and allowed for, an understanding of "hygiene" as the complex, multifarious, interwoven subject it is.

Similarly Future Food which, as the old German idiom would have it schaut über den Tellerrand hinaus, looks over the edge of the plate, looks beyond food per se, and explores the complex, multifarious, interwoven realities our food embodies; and to do so takes the visitor on a journey analogous to the path our food takes on its way to our plate: from production to trade to purchase.

In essence the production of food isn't difficult; becomes however increasingly complex as society becomes increasingly complex. An increasing complexity that both demands and inspires ever evolving approaches to food production. A process discussed in Future Food's opening chapter through explorations of four such approaches, starting with the reform movements of the late 19th/early 20th century, those proto-hippies who in the face of increasing industrialisation and urbanisation sought to work in harmony with nature rather than to dominate it, and thereby stand at the origins of contemporary organic farming and secular vegetarianism. Industrialisation and urbanisation weren't however to be stopped, and in their growth, and for all their growth as components of the complex network of systems within which our planet sits, brought with them ever new challenges, problems, complications, also in context of food production; answers to which are explored in the sections, Optimising What's There with its robotics, drones, computer models et al as technological answers to the challenges and problems of contemporary mass, industrial, food production and The Rural in the Urban, with its aquaponics, community gardens, vertical farming et al as answers to the challenges and problems of not only feeding, but helping ensure the food security of, contemporary cities.

The fourth approach to food production discussed in Future Food's opening chapter concerns itself less with how one produces, as with what one produces; or as the official guide book to the 1911 Dresden International Hygiene Exhibition noted, "Many will be surprised to learn that, for example, the rabbit is a farm animal, and provides for a juicy roast that is nutritionally equivalent to beef."2 A nice example of how previous understandings become lost in periods of rapid change, rabbit having been eaten for centuries, and an invitation to explore alternative food sources, both previously known and newly discovered, repeated in Future Food in the section Other Foods with presentations of, for example, synthetically produced meats as an alternative to farming, or insects as a source of protein, a protein source known to, and enjoyed in, many global cultures, but which we in Europe have never taken to. Or at least, not yet.

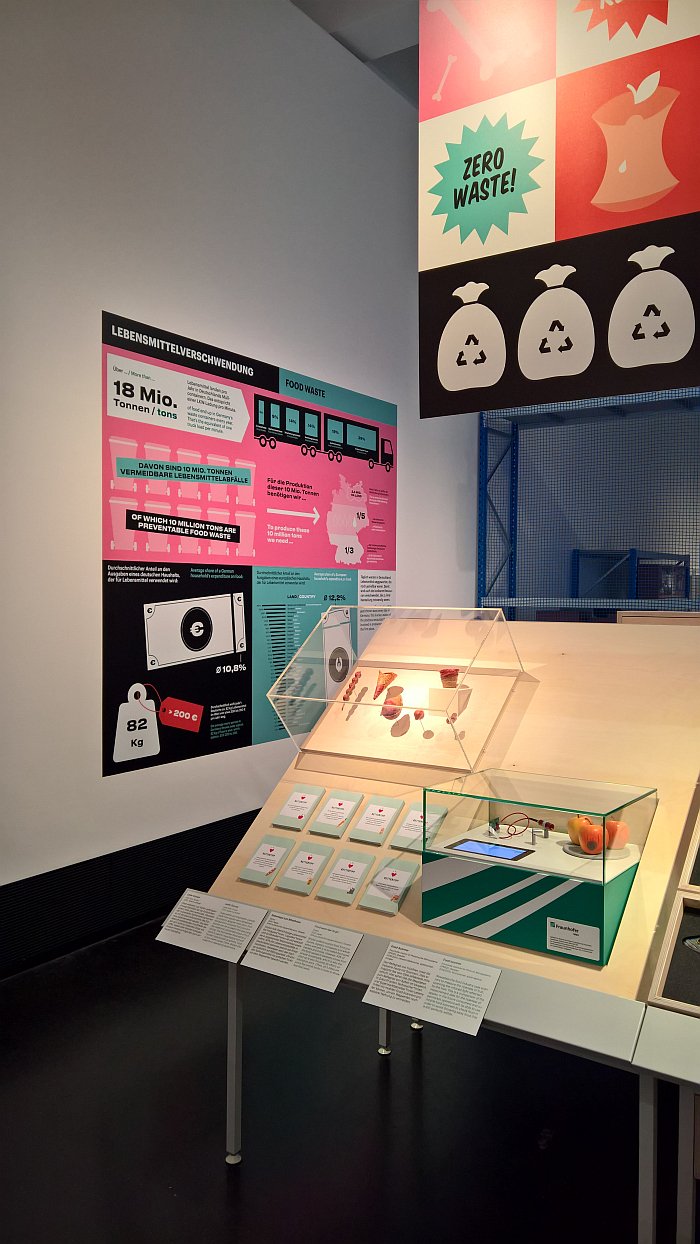

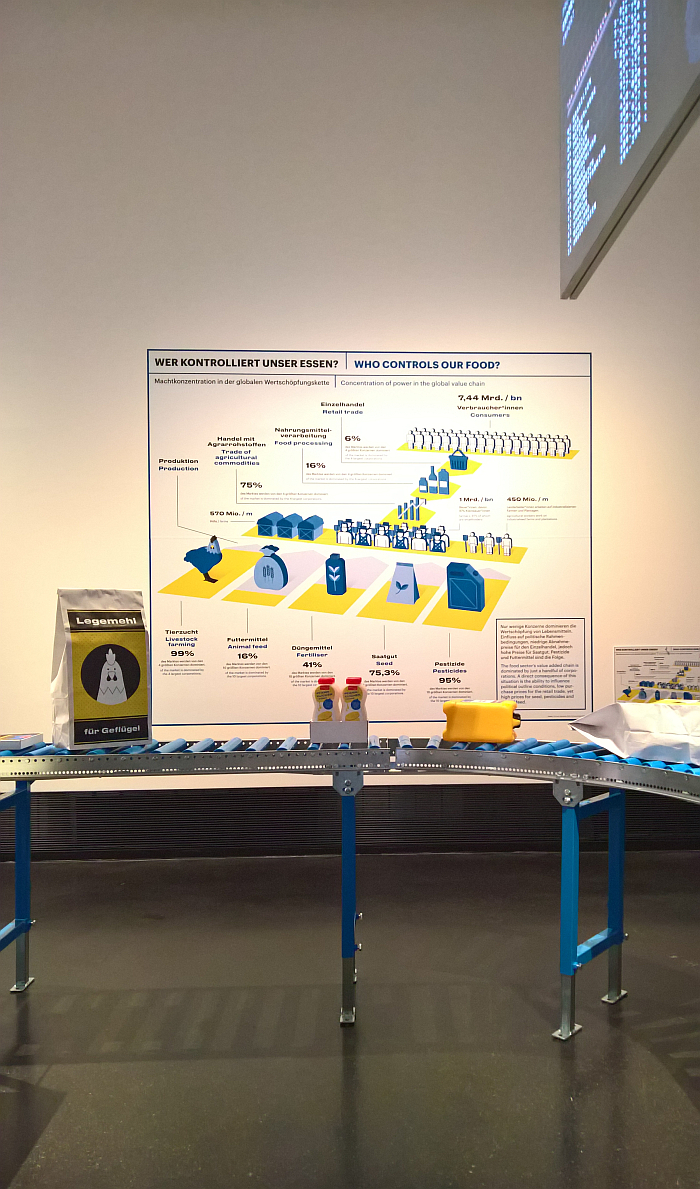

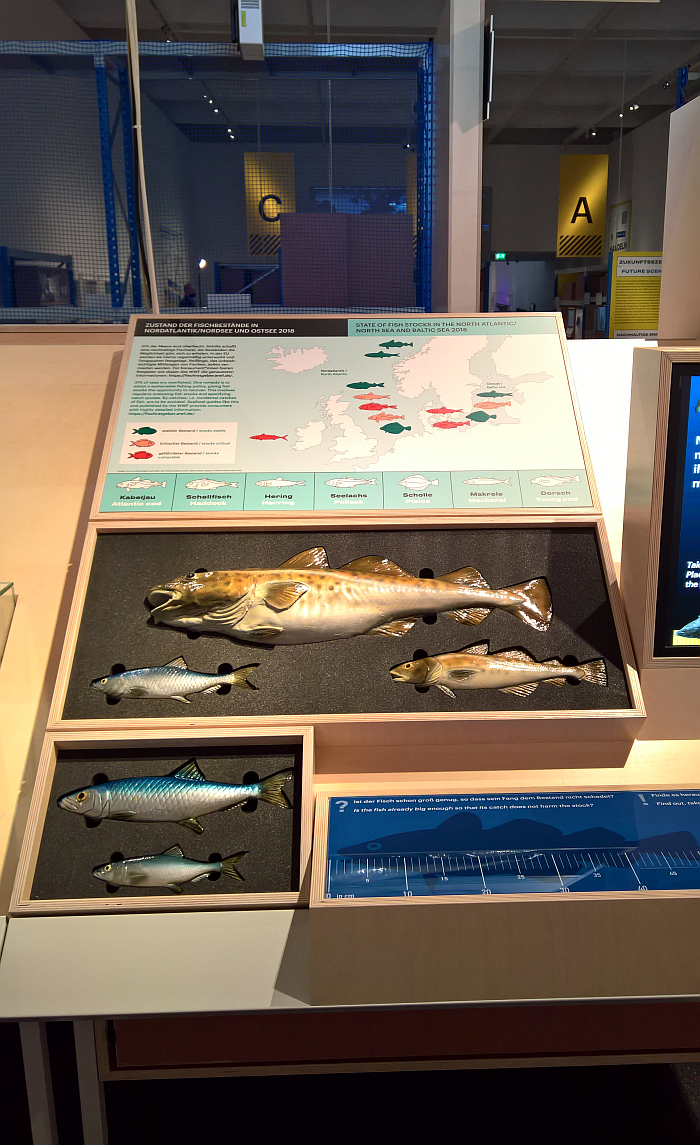

Once produced food needs to reach the consumer. Back in the day that was easy, the producer was the consumer, or lived very close to the consumer. Arguably one of the first foodstuffs that didn't comply to that norm was the salted herring the traders of the Hanseatic League transported from the North and Baltic seas to the the newly Catholicised peoples of the Alps, a region where herring are in short supply, and a seasonal trade with a low carbon footprint. Today in our globalised economy foodstuffs of all kinds travel the world continuously, and that not necessarily only from places of plenty to places of scarcity; the result being a global machine dependent for its existence on our continued consumption of the food it produces and transports. And a machine visualised in Future Food's second chapter through a series of tables and maps charting, for example, the relatively small number of, correspondingly large, companies involved in feeding and running that machine or the discrepancy between the calorific value of various foodstuffs and their monetary value, that those foodstuffs which bring us least, tend to bring the food industry most.

In addition to exploring the nature of our contemporary food machine Future Food also discusses the (hi)story of and contemporary developments in the production and trading of three globally relevant and important foodstuffs: chicken, soya and sugar. The former as an example of, and amongst other aspects, the economic importance, and (political) power, of food as a commodity; the centremost as an example of, and amongst other aspects, the environmental impact of the global food industry; the later as an example of, and amongst other aspects, the juxtaposition of many foods as simultaneously a pleasure and a poison, and also through slavery of the brutality and inhumanity previous generations were prepared to accept for the joy of rotting teeth and obesity. Beyond the conventional, accepted, system, the second chapter of Future Food also discusses examples of alternatives including a comparison of two of the five scenarios the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, PIK, explored as possibilities for the year 2050: on the one side a civil society centred Sustainable Nutrition approach which, so the research, would, amongst other factors, result in more seasonal produce and greater contact between consumers and producers, and on the other side a High-Tech Nutrition approach under which a small number of technology conglomerates control food supply, a, if you so will, Californiafication of food supply, and which, as the exhibition notes, could help "reduce malnutrition and overeating as well as poverty and inequality" but could in doing so put a heavy burden on the environment while harbouring, as yet, not fully understood risks.

Two scenarios which reflect so much contemporary debate about the direction global society should, must, take; and two scenarios which, if either were ever fully realised, would fundamentally alter the way we purchase food.

A process that has been continually evolving for centuries, and which is discussed in Future Food's third chapter within of one of the more popular contemporary forms, the supermarket, and through the four criteria the curators define as central to the decisions we make when choosing what to eat: price, sustainability, taste and health. The first three being, arguably, central, defining, criteria for our general consumption decisions; health alone being specifically related to food consumption, and consumption, and also, to return briefly to 1911, representing the, "basis of individual well-being and the prosperity of nations". A fact which makes food particularly susceptible to the dark arts of marketeers and the untroubled consciences of snake oil sellers. Something particularly relevant in our contemporary medial world, where if there isn't "an app for that", there is definitely a magazine, blog, podcast, video and/or underemployed celebrity to explain not only what you should be eating, but how it should look before you eat it. And the continual, and ever accelerating, parade of new t****s, fashions and compulsions which invariably develops.

And which in doing so further exacerbates the already complicated relationship of price, sustainability and taste in our decision as to what food to consume, and consume.

Thereby making the question "what will we eat tomorrow?", all the more difficult to answer.

Future Food doesn't, can't, provide such answers, but does, for all through the path it takes from production to trading to purchase, develop a framework which allows you to approach answers; wandering that path underscoring as it does the complex inter-relationships between the three components, and leading one to the near inescapable conclusion that the choices we, individually and collectively, make concerning the food we consume, and consume, feed back through the system and define how food is produced, traded and sold. That it always has been so, and always will be so. And that solving, balancing, the contemporary price, sustainability, taste, health matrix is not just the basis of decisions on what we purchase, but the basis of the decisions as to how food is produced and traded. That how we, individually and collectively, balance the contemporary price, sustainability, taste, health matrix influences realities über den Tellerrand hinaus.

And which leads to the very obvious and urgent questions of our relationship to food, of the role of food in our lives, role of food in our societies, the question why we eat what we eat? Questions whose answers, as Future Foods helps clarify, lie in the individual and the collective: while some decisions are based in shared cultural, social, tradition, et al factors, for example whereas silk moth larvae have long been eaten at the eastern end of the Silk Road, at the western end they remain largely unknown as a foodstuff; others are based on more personal factors, be that, for example, the question of what can I afford, arguably the oldest factor in determining what foodstuffs one purchases, or food as the basis for the construction of an identity, as a component of a sense of belonging, through for example consuming the latest fad. Fear Of Missing Out as a reason for consumption.

Considerations which underscore the complexity of the food consumption decisions we make, but which, again as Future Food helps clarify, can not and must not be allowed to distract from the necessity of questioning the consequences of our decisions, individually and collectively, to eat what we eat. And there will be consequences, there are consequences to all decisions; the question is are we aware of them and are we prepared to accept them? In terms of food Future Food can help make you aware of them and provides a platform for personal reflection.

Whereby a not irrelevant fact is that Future Food was initially planned to open in late March, then came Corona and the opening was delayed for two months.

And although in that two months nothing has changed in terms of the exhibition's content, the exhibition's context has changed fundamentally. Certainly in context of the, for want of a better phrase, "global north", that principle arena within which Future Food is concerned, and where Covid-19 has forced a much brighter light to be shone on the realities of global food production, distribution and retail than is normally the case; a light which has illuminated not only many of the weaknesses of the contemporary system, but for all the inequalities the contemporary system creates and fosters, that the brutality and inhumanity of 18th century sugar production hasn't vanished, just evolved, and that both in the "global north" and the "global south". And which in doing so helps bring into sharper focus the need for us all to reflect on the contemporary food industry, on our relationship to the food we eat, on why we eat what we eat, on the global consequences of decisions we in the "global north" make about our food.

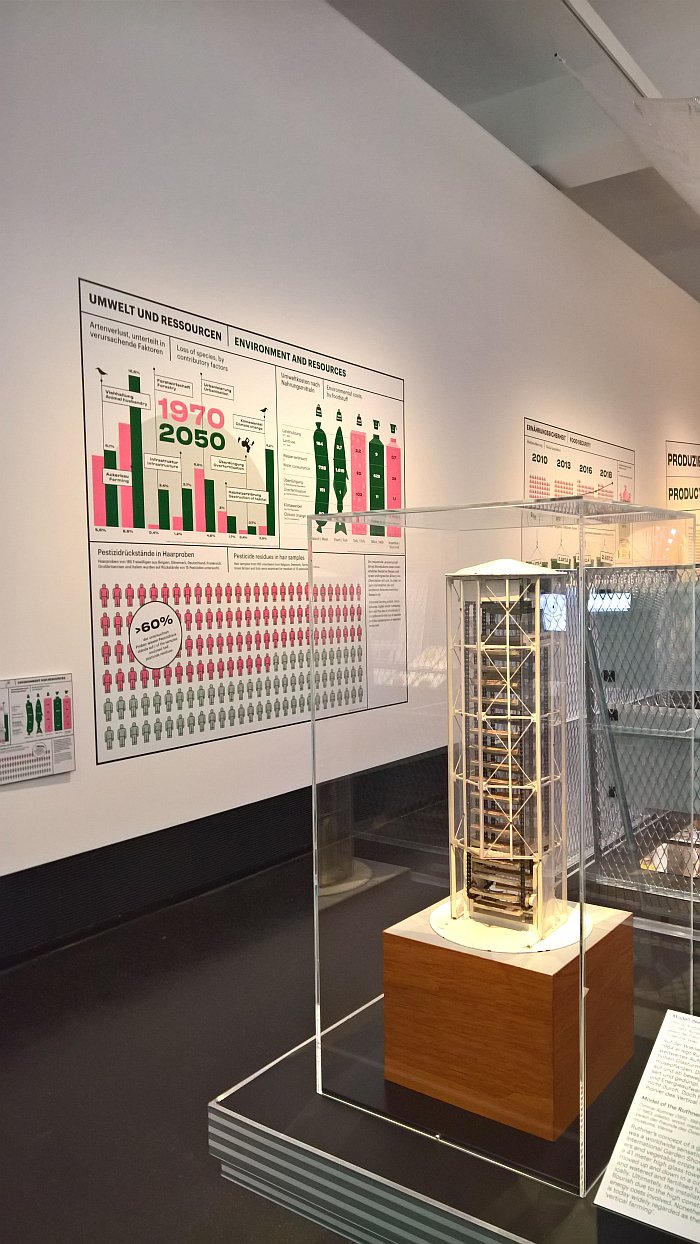

In addition wandering the path laid out by Future Food elucidates that in terms of food, as in terms of near all facets of contemporary society, there is little truly new, that much of what we call "new" is re-imaginings of the existing in new contexts and with the aid of new materials, new technology, new understandings. Something particularly satisfyingly observed in, and amongst other examples, the long history, and manifold contexts, of vegetarianism; in the brief discussion on vertical farming undertaken in context of the growing tower Othmar Ruthner developed in context of the 1963 Wiener Gartenschau, but which couldn't establish itself, juxtaposed with contemporary Singapore where in context of, for example, the company Sky Greens, vertical farming has firmly established itself; or on Europeans eating insects, or not, a proposition which Vincent M. Holt's 1885 book, Why Not Eat Insects? demonstrates has been around a while, but arguably has stronger arguments in its favour today than it did then. Or ever has.

And realities which help indicate that wherever our path takes us in the future, we will invariably find a model and inspiration in the past.

In terms of food as with so, so much in life.

Presenting a lot of content in a relatively compact space, a space that, arguably, could be double the size and still feel a little restricted, one can on entering Future Food initially feel a little overwhelmed by the density of the display, we certainly did; however, it was admittedly our first exhibition since February, and so we are a little rusty. But take time to stop, breath, relax and you will quickly find your way into and through a very open, accessible and logical narrative; a narrative which takes a very critical position towards and of the contemporary global food industry without, as far as we interpreted the presentation, fundamentally questioning it. Much more questioning its current forms, structures and foci and underscoring that reform is necessary. The nature of those reforms being left to each and everyone to consider for themselves, and subsequently debate in an open discourse with others. A necessary public discourse of such a communal subject symbolically alluded to in Future Food's final room through a large banquet table laid out with a feast of contradictions and incompatibles concerning the future of our food, our food industry.

In addition to a wide range of disparate objects ably supported by bilingual German/English texts, Future Food presents, discusses and explores its many themes and positions through films and video interviews, numerous clear, comprehensible, and for all informative charts, graphs, maps et al, and a selection of art and conceptual design projects, including, and amongst others, photographs from Ingrid Pollard's Self Evident project which employs foodstuffs as conduits to explore British colonialism; Anne Vallyer-Coster's 1767 Still life with ham, bottles and radishes, the large ham at its centre underscoring food as a reflection, confirmation, of status, that while the 18th century French nobility could afford the ham, the working class could, on a good day, just about afford the radishes lying next to it; or Jinhyun Jeon's Sensory Stimuli cutlery conceived with the aim of enhancing the gustatory experience. And projects which help set Future Food's myriad themes in more abstract contexts, an important form of reflection for such a complex, multifarious, interwoven subject.

A complex, multifarious, interwoven and important subject, for as Richard Morgenthal's 1950s stain glassed window in the Deutsches Hygiene-Museum proclaims "Health is the greatest asset of humanity". And good health requires not only good hygiene, but good food.

The question as to what is good in terms of hygiene and food isn't difficult to answer, the question as to how to ensure that all receive that is, as Future Food elucidates, not only much more complex, but becoming increasingly so in our increasing complex world, but a question whose answering "is in everyone's power".

Future Food runs at the Deutsches Hygiene-Museum, Lingnerplatz 1, 01069 Dresden until Suday February 21st.

Full details, and a selection of the many, many videos featured in Future Food can be found at www.dhmd.de/future-food

1Vorwort, Offizieller Führer durch die Internationale Hygiene-Ausstellung, Dresden 1911 und durch Dresden und Umgebung: mit einem Plan von Dresden, Druck und Verlag von Rudolf Mosse, Berlin, 1911

2Offizieller Führer durch die Internationale Hygiene-Ausstellung, Dresden 1911 und durch Dresden und Umgebung: mit einem Plan von Dresden, Druck und Verlag von Rudolf Mosse, Berlin, 1911, page 45

And as ever in these times, please familiarise yourself in advance of a visit to the exhibition with the current ticketing, entry, safety, hygiene, etc rules and systems. And during your visit stay safe, stay responsible, stay curious....