Christa Petroff-Bohne arrived a trifling couple of minutes late for the opening of Beauty of Form.

And was most apologetic, apologised for keeping us all waiting.

Whereby, we couldn't help thinking, it is much more us, all, the international community, who should be apologising for keeping Christa Petroff-Bohne waiting for such a comprehensive and rounded recognition of her work and career.........1

Born in Colditz, Sachsen, on February 12th 1934 Christa Bohne initially trained as a ceramic painter at the Steingutfabrik Colditz; a training which, in many regards, not only formed the foundations on which her subsequent career was built, but which has something joyously ironic about it given how her career would develop from that foundation. And the reduced, and astutely, unadorned works her career would not only bring forth and which would largely define that career, but which stand at the heart of her design understandings.

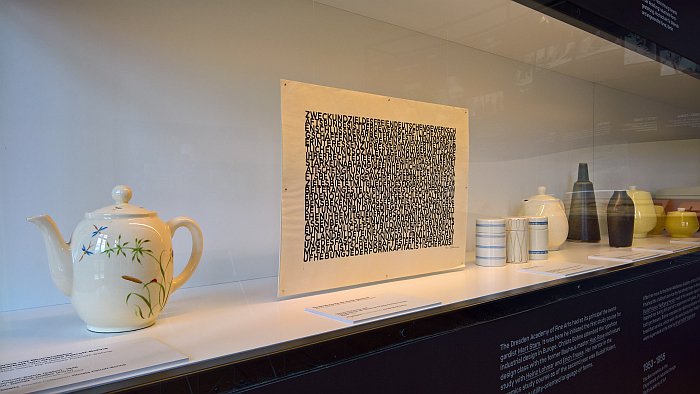

Understandings which began to take on more concrete, ceramic?, dimensions in 1951 when, and although aged just 17, and thereby technically to young to enrol in an art college, Christa Bohne first passed the entrance exam for, secondly passed the entrance committee for, and subsequently was allowed to enrol in, the Hochschule für Bildende Künste Dresden, an institute established in 1949 through the merger of Dresden's fine art and applied arts schools, and under the rectorship of Mart Stam, who in 1950 had left Dresden to take up the position of Rector at the Hochschule für angewandte Kunst Berlin; and at a moment when the so-called Formalism Debate was beginning to fade. As oft discussed in these dispatches; in the early 1950s the East German leadership decided that International Modernism, and for all Bauhaus, was a decadent western sickness and an enemy of the people. Until 1953 when Stalin's death, and the arrival of Nikita Khrushchev at the head of the USSR, led the DDR leadership to, and contrary to their previous unshakable conviction, the opinion that formally reduced, material light, mass producible objects and buildings may be preferable in aiding and abetting the post-War reconstruction effort than heavily decorated, material intensive, Neoclassicist works.

1953 being thus an important year for Christa Bohne's future career.

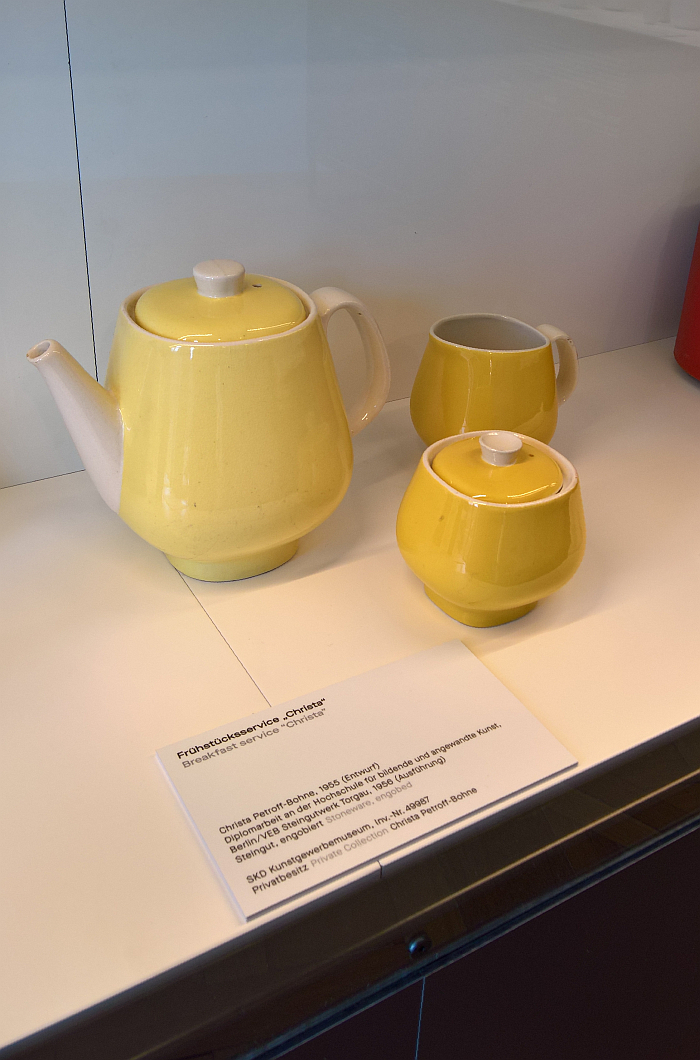

Also because in 1953 the industrial design department in Dresden closed and was integrated with that at the Hochschule für angewandte Kunst Berlin, and where Christa Bohne again just missed Mart Stam, who the East German authorities had finally shooed back West in 1952; and where in 1955 Christa Bohne developed in context of her graduation project a breakfast service which included a cast stoneware coffee pot, milk jug and sugar bowl with charmingly rounded quadratic profiles, a profile which if not entirely new per se, was very uncommon, certainly in 1950s DDR, and a flowing, organic, quadratic which according to Heinz Hirdina demonstrated "the newly obtained freedom for industrial forms"2 that arose following the end of the Formalism Debate. And just as importantly a breakfast service that became Christa Bohne's first commercial work: the VEB Steingutwerk Torgau, with whom she had cooperated on the project, launching the service in 1956 under the name Christa, and a service from which over the next eight years some 60,000 component parts were produced. Which we believe one can call a successful start to a career.

Especially when one does the math and calculates that at the launch of Christa breakfast service, Christa Bohne was just 22.

Following her graduation Christa Bohne spent a year working in the Institut für industrielle Gestaltung, an institute established by Mart Stam on his arrival in Berlin, an institute charged with serving as a link between the college and industry, a platform to ease the development of new products for industry, an institute whose early staff members included the likes of Marianne Brandt, Erwin Andrä or Albert Krause, and an institute which following Stam's departure became increasingly subordinate to the ruling SED, and thereby increasingly less about innovation and more about doctrine. And an institute that offered the young, ambitious, Christa Bohne little.

Which is arguably one of the reasons she gladly accepted Professor Wolfgang Henze's offer of a post-graduate research position, a so-called Aspirantur, at the Hochschule für bildende und angewandte Kunst Berlin, a position which gave her the time and freedom to not only develop her own understandings of and approaches to design, but the time and freedom to develop those understandings through her own projects. Projects such as new bath/washroom utensils for and with the Steingutwerk Dresden; sinks, toilets et al which were never produced, not least because, as Christa Petroff-Bohne explains,3 the new forms she developed for the sinks, toilets, et al, despite being formally, artistically, well received in Berlin, would have meant changes in the machinery and production processes in Dresden. Expensive changes. And there was neither the money nor the flexibility in the late 1950s DDR economy for such. And thereby a project which exposed Bohne to the reality that form-giving is only part of the industrial design process, that the forms you give must also be producible by industry.

The freedom of the Aspirantur also allowing Christa Bohne to explore other materials, to move away from ceramics, something she achieved most notably in metal and in cooperation with VEB Auer Besteck- und Silberwarenwerke, ABS. Established in 1854 and producing cutlery and silverware under the name Weller until its enforced nationalisation in 1946, the ABS management decided in the mid-1950s to reorganise their product portfolio, to cease production of those lines which were no longer relevant, for all those heavily ornate, and materially heavy, lines, and, and most importantly, to work with an industrial designer on the development of new, contemporary, lines. Something that wasn't self-evident in the 1950s, a period when industry, generally, still viewed the industrial designer with mistrust, if not outright hostility, and that not just in East Germany, but globally.

Through the mediation of Albert Buske, a former colleague of Bohne's at the Institut für angewandte Kunst, Christa Bohne became that industrial designer for ABS and in 1957 the first fruits of the cooperation were launched with the 541 cutlery service, a service which took an existing in-house design and developed the formal language; an evolution of the existing that wasn't so dramatic that it couldn't be produced on the available machinery in Aue, and, and arguably equally importantly, an evolution rather than revolution in form that it was hoped wouldn't alienate customers. Which it didn't, much more it seemed to excite them: at its launch at the 1957 Leipzig Spring Fair the 541 service attracting customers not just from across eastern Europe, but Finland and Denmark. Who knew that in the 1950s Scandinavians were buying cutlery from East Germans......4

And, and continuing to do the math, at the launch of the 541 Christa Bohne was 541 just 23

And with a lot still ahead of her.

Not least for ABS, the 541 collection representing the first in a long succession of successful products developed by Christa Bohne for ABS, including, and in addition to further cutlery collections, general objects for the catering and hospitality industries including serving trays, coffee pots, condiment sets, egg cups, ice cream bowls et al; and works that in many regards stand as key works in Christa Petroff-Bohne's oeuvre, or as Heinz Hirdina opines, "nothing reveals more about [Christa Petroff-Bohne] than the designs for hotels and restaurants as the centre of her design practice"5

Not that design practice is/was the only centre in Christa Petroff-Bohne's universe.

Following the completion of her Aspirantur in 1959 Walter Funkat, Rector at the Hochschule für Industrielle Formgestaltung Halle, the contemporary Kunsthochschule Burg Giebichenstein Halle, offered Christa Bohne a teaching post at the school, an offer which although Petroff-Bohne describes as "alluring"6 she turned down; accepting however in the same year an offer from Rudi Högner, the newly appointed Professor für Industrielle Formgestaltung at the Hochschule für bildende und angewandte Kunst Berlin, to become his assistant; the start of an academic career that with her appointment in 1966 as Dozent became a formal teaching career, a teaching career which Christa Petroff-Bohne describes as her "calling",7 which she would continue to practice at the Kunsthochschule Berlin until 2001, from 1978 as head of the ceramics department and from 1979 as Professor.

Among the more notable, certainly most noteworthy, elements of Christa Petroff-Bohne's teaching career is her development of the Basics of Visual Design programme at the Hochschule Berlin.

A compulsory second year course which Rudi Högner had initiated following his arrival in Berlin from Dresden in 1953, Christa Bohne took Högner's, by all accounts, less than systematic approach, and developed in the course of the late 1960s/early 1970s a programme which takes the students through a series of eight successive Übungskomplexe, Practice Complexes; a path which sees the students move progressively from two dimensional graphics/compositions, over two dimensional depictions of three dimensional bodies, on to solid objects, which are abstracted and deconstructed before elements such as colour or material are introduced and ultimately the whole is considered in context of space. A succession of exercises Petroff-Bohne discussed in a series of articles in the East German design magazine Form+Zweck,8 and which she notes, was a programme so conceived and arranged "that despite the limitation of a defined goal, [it] allows a broad development of the powers of imagination and the possibility of differentiated objective and subjective interpretations."9

Parallel to her academic career Christa Petroff-Bohne remained active as a designer cooperating with firms as varied as and amongst many others, VEB Lederfabrik Burg, Staatliche Porzellanmanufaktur Meißen, VEB Thüringer Industriewerk Rauenstein, and in 1988 almost cooperating with Rosenthal AG, and thus a porcelain manufacturer from the imperialist West; and a project as Beauty of Form succinctly explains through both objects and correspondence, was very advanced, before it was cancelled. That it was cancelled having nothing to do with the politics between East and West, but the politics within Selb, Bavaria, home of Rosenthal, and where Philip Rosenthal, who throughout the post-War decades had not only led but defined the company, found himself replaced with a new management team. A new management team with, as with most all new management teams, new ideas.

Following German unification industrial contracts became rarer and Christa Petroff-Bohne's focus became her teaching at the Kunsthochschule Berlin-Weißensee, until her "retiral" in 2001 in wake of the decision to close the school's ceramics department as part of a reorganisation of the school's programme. Were the department still in existence, we genuinely believe Christa Petroff-Bohne would still be teaching there. Such is the energy, verve and passion for design, form-giving and teaching one senses in her company.

And because we're all still doing the math, at her "retiral" in 2001 Christa Petroff-Bohne was 67 and had enjoyed a career that began as a 14 year old trainee ceramic painter in Colditz and in the 50 years since she enrolled in the Hochschule für Bildende Künste Dresden had seen her develop not only into one of the most interesting East German industrial designers, a designer who through her understandings of form, function and materials helped develop and evolve understandings of and relationships to objects, but also saw her become one of the leading design educators in eastern Germany, anyone who studied at the Kunsthochschule Berlin/Kunsthochschule Berlin-Weißensee from the mid-1960s until 2001 undertook Petroff-Bohne's Basics of Visual Design design class.

Which poses the question, why, how could, Christa Petroff-Bohne slip from popular view...........?

While there are invariably a myriad, of equally invariably interplaying, explanations, viewing Beauty of Form, and its presentation and exploration of Christa Petroff-Bohne's work and career, two occur to us as most probable.

On the one hand, a large component of Christa Petroff-Bohne's contribution to post-War design was as an educator. And that is rarely something that is going to be acknowledged outwith the school(s) where you teach. Then or now. For industrial and product design, as we all know, is about objects. They obviously aren't. That's a ludicrous position. But in the popular understanding of industrial and product design they are very much about objects, design education isn't a subject that interests the wider public; although, and as we never tire to exhort on our annual #campustour, it very much should. And in which context, as we never tire to note, we are always happier at design school summer exhibitions which don't just present graduation projects but present the results of semester projects and the basics, fundamentals, courses, for in such courses one can approach an understanding of not only what the students are learning, but for all how they are learning. A how that not only allows one to approach a better understanding of the school, but of the understandings of and approaches to design that are likely to develop in the students.

Similarly, in Beauty of Form where one of the genuine joys is that it allows one to approach an understanding of that how as developed and taught by Christa Petroff-Bohne. And by extrapolation of Christa Petroff-Bohne's approaches to and understandings of design.

Aside from a collection of form studies developed by Petroff-Bohne's students, Beauty of Form takes the visitor, via a very intelligent presentation format, through the Basics of Visual Design course's eight successive Practice Complexes; and in doing so allows one to approach an understanding of how the students were guided through, motivated to cultivate, develop and evolve, considerations on understandings of forms, of relationships, of colour, of proportions, of scales, of materiality etc, etc. Allows one to approach a better understanding of Christa Petroff-Bohne's position that "the mediation of design basics [should be] methodical, systematic and didactic, so that logic and emotion can develop in partnership",10 should in doing so allow the students to develop their receptivity and sensitivity to and of forms, and that such is a process in which "words are only of limited use" rather it is an essentially visual process, one of constant study, comparison and modification.11

And a process that for all its similarities with those basics, fundamentals, courses developed in the first half of the 20th century, arguably most popularly as represented by the Bauhaus Vorkurs, wasn't a course based on theoretical positions but primarily on Christa Petroff-Bohne's own understandings and approaches. Understandings and approaches which, logically, were based on her own education, the research undertaken in course of her Aspirantur, and not unimportantly, on her experiences as an industrial designer.

Which Christa Petroff-Bohne very much was, if most actively in fields that lead onto our second understanding of her slipping from popular public view: the relative anonymity of the key works in her oeuvre.

Whereas we all tend to know, and history tends to remember, the designers of shelving systems, motorbikes, chairs and other objects with which one forms an emotional bond and develops associations; less so the name of the designer of crockery and cutlery for the hospitality industry. Then or now. Your work may be near ubiquitous and, literally, pass through the hands of a majority of the population, something particularly so in the case of Christa Petroff-Bohne, many of whose works were produced continuously from the 1960s to the 1990s and were used by institutions such as Mitropa and Interhotel, but only very few users are going to note your name, far less appreciate the design understandings and positions inherent within the works, the development involved in realising the objects. Or indeed that the objects were designed. Much of the work on show in Beauty of Form, much of Christa Petroff-Bohne's oeuvre is of that deliciously obvious type which belies the fact that someone designed it. That someone could have designed it. Surely it has always existed?

And which in many regards much of Christa Petroff-Bohne's works have. Christa Petroff-Bohne didn't invent the soup spoon, the wine cooler, the serving tray or the ice cream bowl, but she did develop her own interpretations of such, interpretations originating not only in her understandings of form and functionality but in her understandings of the relationship between designer and client, designer and user.

In a 1987 magazine article Christa Petroff-Bohne discusses the realities of designing for the catering industry noting the need for "a high degree of generalisation", not least to ensure a wide scale use that enables the benefit of mass production to be fully exploited, and that, "from the point of view of the guest, the serving staff, the kitchen staff and the technical process in the kitchen, different and expanded requirements arise."12 Realities which make finding that "high degree of generalisation" a little, lot, more complicated. Involves deeper research, observation and a more considered formal development.

The research and observation Christa Petroff-Bohne undertook on-site in hotels and restaurants; the considered formal development, that process of constant, repeated study, comparison and modification taught in her Basics of Visual Design course and whose aim in an industrial context was to "orientate subjective creative will on objective criteria",13 undertaken in her studio; and, as one can observe in Beauty of Form allowed her to develop objects which met not only the functional demands of kitchen staff, serving staff, and technical process in kitchen, but also the functional, and formal demands of the guests; the flowing, organically curved 542 cutlery service Petroff-Bohne created in cooperation with ABS for the Hotel Berlino in East Berlin, a flowing organic curve that as with Arne Jacobsen's objects for the SAS Royal in Copenhagen stands juxtaposed to the dogmatic quadratic of the building, proved so popular that, and given that it couldn't be purchased, guests would regularly take items home with them. One could say, stole them. Which although sounds like a cunning business plan for ABS, proved more of a problem for the Hotel Berlino and led to the development of the alternative, and markedly less flowingly, organically curved 120 collection. If a collection that was no less successful.

And objects, and oeuvre, which remain(s) just as appealing to the contemporary eye, as a general rule Christa Petroff-Bohne's designs have lost nothing of their charm and elegance, have moved with the times and thus stand testament to the truesim of the need for honesty in design, the importance of designing free from fad and fashions, to design based on a solid understanding of what you are designing and why, and with an individually cultivated, personal, understanding of the development of form.

And objects, and oeuvre, which underscore that important as the question why Christa Petroff-Bohne could slip from popular view unquestionably is, and important as approaching answers equally unquestionably is, just as important is that Christa Petroff-Bohne is once again in popular view. That her contribution to the evolution of design, to the (hi)story of design is back in view. That her works are back in view.

As ever with exhibitions in the Wasserpalais at Schloss Pillnitz the spatial limitations not only provide a challenge for staging exhibitions, but also a pre-defined framework; something elegantly employed in Beauty of Form to take the visitor on a thoroughly enjoyable, bilingual German/English, tour through Christa Petroff-Bohne's career as an active designer and her career as an active educator, the two treated separately but not independently, the two weave through and merge with one another with the same natural ease that one imagines they did throughout Christ Petroff-Bohne's active career.

And in doing so Beauty of Form is an easily accepted invitation to explore, consider and reflect on Christa Petroff-Bohne's biography, career and contribution to the development, evolution, of design and design understandings.

An invitation to explore, consider and reflect on Christa Petroff-Bohne's works, formally and functionally. The former more often than not seeing objects reduced to a vague idea of the intended objects, Christa Petroff-Bohne's works, and generalising to the point of falsehood, relying to a large degree on the sparing use of a very simple geometric forms. Which as with the soup spoon or ice cream dish, isn't something of Christa Petroff-Bohne's invention, is a construction principle one can follow backwards over the the geometry of the inter-War functionalists, the stereometry of a Peter Beherns and back through a Schinkel to the antiquity of Rome and Greece; but a construction principle which Christa Petroff-Bohne applies with a lightness and dexterity, with a fine feeling for relationships, scales, composition and proportion, and through the regular use of a sweeping, flowing, organic, interruption, an implied emotion that brings a naturalness to the strictly functional, that in many regards makes it her own.

The functionality in the works existing both in their usability, in active situations, in the exhibition there is, for example, a video in which Christa Petroff-Bohne succinctly explains the intuitive operation of her coffee pot for ABS, and also in passive situations, for example in their stackability, something achieved, much like Wilhelm Wagenfeld in his 1930s glassware for the Vereinigte Lausitzer Glaswerke Weißwasser, through the removal of all handles, knobs and decoration. And in which context, Petroff-Bohne's vegetable serving dishes with lids owe more than a little debt of gratitude to Wagenfeld's pressed glass work, a debt we are certain Petroff-Bohne would acknowledge and which in no way detracts from her own design. Which is her own design.

Beyond such direct functionalities, other, applied, functionalities can be located in, for example, the material reduction that Petroff-Bohne's design approach and understandings naturally lead to, and which equally naturally increase the economy of their production, while their anonymity, almost invisibility, achieving, if one so will, an ecological functionality. A sustainability. In context of the exhibition Shaping everyday life! Bauhaus modernism in the GDR at the Dokumentationszentrum Alltagskultur der DDR Eisenhüttenstadt we noted that the open, flexible design of many DDR products helped ensure a long lifecycle, an that "objects in the DDR, unlike political or economic policies, being transparent, democratic and conceived to last." Something similar can be understood in the forms of Christa Petroff-Bohne, forms which one can also decsribe as transparent, democratic and conceived to last; albeit a longevity that comes not from an open flexibility, but a universality, "a high degree of generalisation." Something that one can not only understand very well in Beauty of Form, but learn from.

An invitation to explore, consider and reflect on Christa Petroff-Bohne's biography, of the character that underscores that biography. Through doing the math, and reading a little deeper, one understands that at 17 she persuaded an art school selection committee to allow her to enrol, despite being too young; at 22, and freshly graduated, was discussing and arguing with the engineers, technicians and managers at ABS, explaining why her designs should be produced, and that despite the opposition in the factory her designs were produced: at 25 was assistant to a Professor at one of East Germany's most important design schools, having turned down an "alluring" position at East Germany's other most important design school. And that, one must note, as a female. Now isn't the time nor place for a discussion on gender equality in the DDR, important a subject as it is, but a quick look at the photos in the catalogue14 show Christa Petroff-Bohne in the company of (all but exclusively) men, be that students, academics, politicians, industrialists. One could argue she achieved all she did in an environment in which it wasn't foreseen that she should achieve a fraction of what she did. And that needs to be acknowledged as much as her work.

And also an invitation to explore, consider and reflect on in a more differentiated manner design in East Germany. In a more differentiated manner post-War design in Germany. Considerations on the similarities of much of Christa Petroff-Bohne's understandings, approaches and work with those being developed parallel in West Germany, and reflections on the fact that until 1945 both East and West had enjoyed a shared architecture and design history, and so why shouldn't they go similar ways post 1945? Considerations and reflections which although occupied us a lot in Dresden, and have continued to do so since Dresden, we won't discuss here as it would (a) (further) distend the spatial limitations of the internet, and (b) because having made Christa Petroff-Bohne wait so long for such a comprehensive and rounded recognition of her work and career, Christa Petroff-Bohne, her biography and her work really should be the focus......

Beauty of Form. The Designer Christa Petroff-Bohne runs at the Kunstgewerbemuseum, Schloss Pillnitz, August-Böckstiegel-Straße 2, 01326 Dresden until Sunday November 1st

Full details can be found at https://kunstgewerbemuseum.skd.museum/beauty-of-form/

And as ever in these times, if you are planning visiting please familiarise yourself in advance with the current ticketing, entry, safety, hygiene, cloakroom, etc rules and systems. And during your visit please stay safe, stay responsible, and above all, stay curious….

1Beauty of Form isn't the first exhibition devoted to Christa Petroff-Bohne, most notably in 1999/2000 the Deutsches Porzellan Museum in Hohenberg an der Eger staged the exhibition Christa Petroff-Bohne. Eine ostdeutsche Designer-Biographie. However that was 20 years ago, and since then there have be nowhere as many as one could resonably expect. In addition, the publication to Beauty of Form is a much more comprehensive, varied and fulsome work than that for Eine ostdeutsche Designer-Biographie, and also Beauty of Form is not only being shown in Dresden but will also be shown at the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg, and thus is a much larger, more involved, project. And so while our introduction is not factually correct, we'd argue in spirit it is spot on.

2Heinz Hirdina, Auf besondere Art verwickelt, in Hein Köster, Christa Petroff-Bohne. Eine ostdeutsche Designer-Biographie, Deutsches Porzellan Museum, Hohenberg an der Eger, 2000

3see Christa Petroff-Bohne, Mein Weg als Formgestalter in Silke Ihden Rotkirch & Jörg Petruschat [eds] Schönheit der Form. die Designerin Christa Petroff-Bohne, form+zweck Verlag, Berlin, 2020, page 230

4In addition, as the Berliner Zeitung, BZ, noted, the 541 found customers in Switzerland, Austria and Holland, while in 1958 some 4000 items from the 541 service were sold on the black market in East Berlin, technically it was unavailable to private consumers, only trade. And the staff at the Institut für angewandte Kunst who, apparently, had a special dispensation to order it. Which many of them did. The 541 was something very new and obviously very desirable in late 1950s East Germany, or at least in East Berlin, according to the BZ demand was notably less in Mecklenburg...... See, Nur ein Besteck - aber es ärgert sehr, Berliner Zeitung, December 14th 1958 page 5

5Heinz Hirdina, Auf besondere Art verwickelt, in Hein Köster, Christa Petroff-Bohne. Eine ostdeutsche Designer-Biographie, Deutsches Porzellan Museum, Hohenberg an der Eger, 2000

6see Christa Petroff-Bohne, Mein Weg als Formgestalter in Silke Ihden Rotkirch & Jörg Petruschat [eds] Schönheit der Form. die Designerin Christa Petroff-Bohne, form+zweck Verlag, Berlin, 2020, page 238

7ibid

8see Farbe - Designausbildung Grundlagen, Form+Zweck, Vol. 13, Nr1, 1981 page 20ff; Materialübungen, Form+Zweck, Vol. 13, Nr.6 1981 page 16ff; Plastiches Gestalten - Didaktik der Elementaren, Form+Zweck, Volume 14, Nr.6 1982 page 20ff;Der Rotationskörper, Form+Zweck, Vol. 15, Nr.4 1983, page 30ff; Quesrchnittsveränderungen, Form+Zweck, Vol. 16, Nr. 3 1984 page 24ff. And also Umfrage zu Itten - Ästhetik und Formgestaltung, Form+Zweck Vol 12, Nr. 2 1980 23-24 All acessible via

9Christa Petroff-Bohne, Zur Ausbildung von Formgestaltern, Künstker und Hochschullehrer, Kunsthochschule Berlin, Beiträge 8/9, Berlin, 1981

10Christa Petroff-Bohne, Empfinden - Erkennen - Erproben - Gestalten, in Hein Köster, Christa Petroff-Bohne. Eine ostdeutsche Designer-Biographie, Deutsches Porzellan Museum, Hohenberg an der Eger, 2000

11Christa Petroff-Bohne, Zur Ausbildung von Formgestaltern, Künstker und Hochschullehrer, Kunsthochschule Berlin, Beiträge 8/9, Berlin, 1981

12Christa Petroff-Bohne, Restaurantgeschirr, Form+Zweck, Vol. 19, Nr 1 1987, page 41-42

13Christa Petroff-Bohne, Empfinden - Erkennen - Erproben - Gestalten, in Hein Köster, Christa Petroff-Bohne. Eine ostdeutsche Designer-Biographie, Deutsches Porzellan Museum, Hohenberg an der Eger, 2000

14Silke Ihden Rotkirch & Jörg Petruschat [eds] Schönheit der Form. die Designerin Christa Petroff-Bohne, form+zweck Verlag, Berlin, 2020 .... Technically not a catalogue, but a book developed in very close cooperation with the exhibition and an exhibition developed in very close cooperation with the book. So near a catalogue as makes no difference.....