The study of vernacular furniture can teach us a lot about not only the development of understandings of furniture, nor only of the development of societies and cultures, nor nor only only about relationships between furniture and wider realities, but also how the position of furniture as a cultural good, as a good embedded in a culture and society, can see furniture serve as a component of projected understandings of heritage and identity, and in doing so can endow attributes on an object of furniture it doesn't naturally, inherently, possess.

Or need.

Something particularly well expressed in the (hi)stories of the straw-backed chair, a.k.a. the Orkney Chair1

"It may at first sight be thought that a more uninteresting and insignificant subject on which to speak than straw could scarcely be chosen", reflected Walter Traill Dennison in his late 19th century paper on the Manufacture of Straw Articles in Orkney, "yet it will be found that the apparent insignificant things in nature become some of them the greatest bane, others the most essential blessings to mankind"2

The Orcadian straw-backed chair counts, without question, amongst the more essential of blessings; and as a subject in the (hi)story of furniture is anything but uninteresting and insignificant.

But let's start at the beginning.

Or as best we can at the beginning.

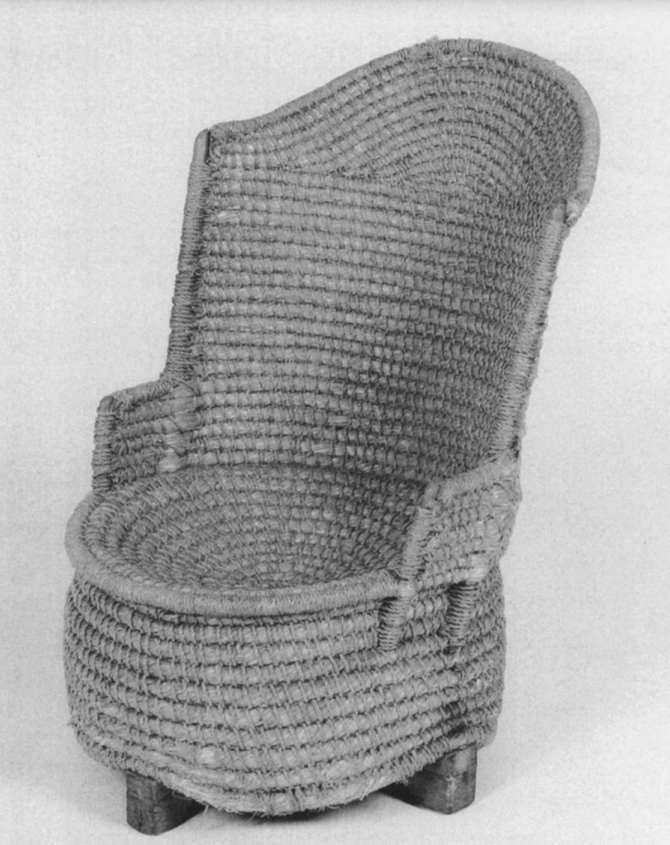

By common consensus, and with all items of vernacular furniture one has little to rely on in context of origins and genesis other than common consensus, rarely your actual fact, thus by common consensus the earliest Orkney straw-backed chairs were...... backless, were, depending on your viewpoint, woven straw baskets upturned and re-functioned as a low stool, or woven circular straw stools which could be upturned and re-functioned as a basket; and which over time developed into low sitting objects with an internal wooden skeleton, a minimal construction entirely shrouded in woven straw, save four stubby feet protruding from the base, and which in addition to a round woven straw seat featured, as Traill Dennison describes, "a half circular back reaching to the shoulders of the sitter"3 A half circular back constructed from tightly woven straw.

That in previous centuries the peoples of Orkney should have employed straw for their chairs shouldn't surprise us. Aside from Vikings, Puffins and an intangible but impenetrable headwind, Orkney's other defining factor is its lack of forests, or indeed trees in any notable number4; a reality which means that wood has never been a central material in Orcadian culture5, relying, as they must, either on expensive imports, or that driftwood which washes up on their shores. And thus for centuries Orcadians have been dependent on locally producible alternatives, among which oat straw was traditionally one of the most important, and a material used for all manner of objects, or as James Omond notes in context of early 19th century Orkney, "what an Orkneyman could not make of straw was, in those times, not worth having".6

And, chairs are, we'd argue, well worth having.

And so the Orkneyman and Orkneywoman wove themselves chairs from their home grown, self-harvested, oat straw.

Sustainability before sustainability was a thing. Or perhaps better put, sustainability when it was how society lived, before mass consumer culture required us to develop sustainability as a thing people could write books about and present podcasts on to distract popular attention from the fact it is entirely our own fault that we were living so out of kilter with our world. But we digress......

Then at some point in the course of the 18th century the Orkney straw-backed chair underwent an important development: its concealed, minimal, wooden skeleton became exposed and more pronounced, the straw seat was replaced by a wooden one, the legs grew. Alone remained the tightly woven straw back.7

Common consensus, that faithful, if not always reliable, companion of ours, has it that the first such straw-backed chair was developed on the island of North Ronaldsay, the most northerly of the Orkney isles, as an alternative to the time consuming process of weaving the base. And logical as that assumption may be, there is, for us, an alternative argument to be made that while unquestionably practical and logical as the early straw-backed chairs were, they would, not least on account of the close proximity of the base to the ground, have lacked durability in the cold and damp of 18th century Orkney. And 18th century Orkney was notable for being cold and damp. And thus alternatives to the straw base would, unquestionably, have been sought.

And found in the wooden chairs that were known and used in 18th century Orkney, it wasn't all straw.

And thus one can well imagine some unrecorded Orcadian, unrecorded North Ronaldsian, coming up with the idea of maintaining the durable and stable wooden base and seat, possibly an existing wooden chair that had become damaged, and applying a straw back; a straw back which reduced the demand for wood, and allowed that wood one had to be used in situations where there was no alternative; a straw back which allowed for much easier repair and maintenance and thus extending the longevity of the chair; a straw back which offered not only a higher degree of comfort but a higher degree of insulation, 18th century Orkney being cold and damp and draughty; a straw back to which a straw hood was added, an extension which aided the insulating effect, from both draughts and noise. Cocooning before cocooning was a thing.

And a wood-based straw-backed construction that moved southwards from North Ronaldsay to became an established feature in the cold and damp and draughty crofts of 18th and 19th century Orkney.

And subsequently much, much, further afield.

And in much, much, less cold and damp and draughty contexts.

"You supplied me with a straw chair in end of November" wrote George Hunter MacThomas Thoms, the, then, Sheriff of Orkney, Caithness and Zetland to the Kirkwall joiner David Kirkness in March 1890, "I wish you to get made & send up another of smaller size - as I propose to send both to the Exhibition to open here in beginning of May to see if it can do good to the industry."8

Whereby it is arguable if in March 1890 there was an "industry" to do good to. Or if Sheriff Thoms helped create one.

And in doing so bringing a little tartan clad mythology, a breath of late 19th/early 20th century romanticism, a perceived cultural symbolism, to an object of rugged, unromantic, daily use.

But before we get to the semantics, let's take a couple of steps backwards.

The David Kirkness who had supplied the chair in question was born on the island of Westray in 1855 and trained as joiner in Orkney's principle town, Kirkwall, before establishing his own business. A business which, at least pre-1890, was, by all accounts, largely concerned with joinery and undertaking, but which included a sideline in straw-backed chairs; one presumes for those townsfolks who wanted one but had only little opportunity to make their own. And also, one further presumes, for both Orcadians who had left the islands and either wanted a touch of home or who simply appreciated the object, and also tourists who visited the islands and either wanted something "authentic" as a souvenir, or who simply appreciated the object.

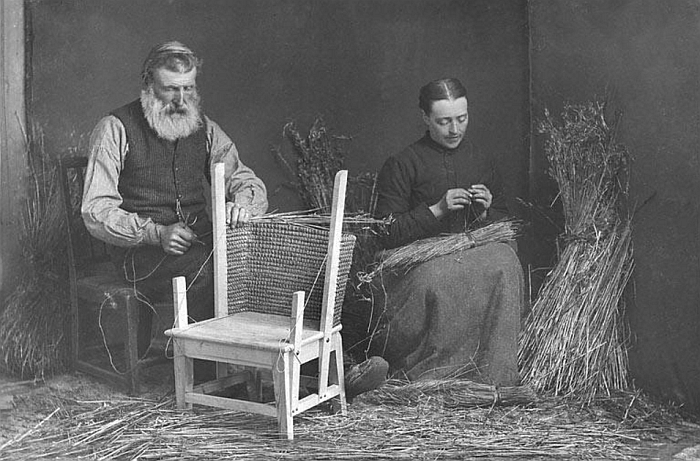

And while Kirkness made the frames for the chairs, the production of the straw backs was undertaken as piece work by home-working rural islanders.

And thus an extension of a, by all accounts, thriving 19th century straw plaiting cottage industry in Orkney; the aforementioned familiarity of Orcadians with the weaving of straw coupled to the need to supplement the meagre incomes of their crofts, seeing many families take on straw plaiting work for mainland UK companies, particularly in context of the straw hat industry.9

A thriving cottage industry David Kirkness, somewhat logically, utilised for his chair backs. A decentralised production process which, not uninterestingly, found a parallel echo in late 19th century South Moravia, where rural home-workers wove the wicker seats for Thonet chairs. And a decentralised production process based on a native skill which, in some regards, helped enable the post-1890 upscaling of that pre-1890 non-industry.

The exhibition Sheriff Thoms referred to in his letter to Kirkness was the improbably named, International Exhibition of Electrical Engineering, General Inventions and Industries staged in Edinburgh between May and November 1890, an unofficial World's Fair, an event closely related to the completion and opening of the Forth Bridge and which sought in the words of The Observer, "to illustrate the present general state of engineering, and of the mechanical arts" and "of the progress of electricity in England and the United States, together with the backward state of electrical science in Scotland."10 Harsh words, but which could be taken as seeking to supply an impetus for improvement. And thus to misjudge the Scottish psyche. An exhibition which attracted neigh on 3 million visitors, which isn't bad for 1890s Scotland; and 3 million visitors who could marvel at exhibits including an electric railway, a demonstration of Thomas Edison's latest phonographic developments, and a telephone via which one could listen to a live concert being performed down the road in Galashiels.11 Just imagine! A telephone on which you can listen to music and follow a live concert in a far off location, rather than just telephoning!!! Weird ideas they had back then!!!

And an exhibition which not only presented electrical and mechanical engineering but also a cultural programme including the de rigueur presentation of "nations", a presentation featuring, and amongst other delights, a Japanese Village, as oft noted Japan was all the rage in 19th century Europe; a Swiss mountain chalet, the 19th century seeing the development of mass tourism and Switzerland with its romantic lakes and romantic mountains and romantic valleys was a preferred destination; and also, logically, a presentation of Scotland. Including a stand hosted by the Scottish Home Industries Association, SHIA.

Established in 1889 by the Countess of Rosebery, at that time one of the wealthiest individuals in the United Kingdom, the principle focus of the SHIA was supporting and promoting craft production from the highlands and islands of Scotland, those industries that a Sheriff Thoms understood existed but which probably didn't; an organisation who were, arguably, most notably active in context of the promotion of Harris Tweed, including achieving its legal protection, effectuating the conferring of, what we'd term today, Protected Designation of Origin status.12 And an organisation whose promotion of native highland and islands industries crafts included a commercial arm which, as Stana Nenadic and Sally Tuckett very neatly phrase it, was "mostly aimed at the high fashion market and had an identity that was built on aristocratic and gentry associations with the highlands and romantic Scottishness."13

It wasn't just Swiss mountain chalets that inflamed 19th century fantasies; equally evocative was the wild romance of the Scottish highlands and islands, with its tartans, stags, inhospitable glens and perceived authenticity. A fascination that became, if one will, institutionalised amongst the British upper classes when Queen Victoria and Prince Albert acquired Balmoral Castle in 1852 as their private highland holiday home. And much as today buying the correct blanket or vase brings you instant hygge, so then purchasing the correct object guaranteed to take you from your Edinburgh sitting room or your London drawing room to the romantic reality of a highland croft.14

And an organisation that in its romantic understandings and associations can, must, also be considered very much part of a reaction to the increasing industrialisation of the late 19th century, an industrialisation neatly embodied in the Forth Bridge, in the "the mechanical arts" being celebrated at the 1890 Edinburgh exhibition; and an industrialisation that initiated a desire amongst sections of society to return to something perceived, understood, as being more natural, more humane, more traditional, authentic. A development most popularly understood in a UK context through the Arts and Crafts movement; a development which was an important point of reference for the emergence of what we term today Art Nouveau.

And a development most closely associated in context of "the high fashion market", with the department store Liberty's of London, a key, let's say, influencer, in terms of clothing, furniture and interiors in late 19th/early 20th century Europe.

And which brings us back to David Kirkness.

The two chairs Sheriff Thoms had acquired from David Kirkness were presented at the 1890 Edinburgh exhibition as part of the SHIA stand, and where they enticed Liberty's to place an order. The why is lost in the mists of time; however, and as with the Orcadian use of straw in chair production, shouldn't surprise us. As a product the straw-backed Orkney Chair can, must, be understood as fitting in almost too well with the prevailing Arts and Crafts understandings of handwork, materials, naturalness, humanity, authenticity, not least because it had a "tradition" as an actual object that went beyond the more abstract "tradition" any trade or craft could provide; and in addition had that "romantic Scottishness", had that breath of wild moors, the taste of heather, the imagery of a Walter Scott, a Robert Louis Stevenson, a Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy. Understandings, associations, symbolism were freely read in the Orkney Chair: freely as in easily; freely as in willingly; freely as in fictitiously. The straw-backed Orkney Chair ticked all the boxes and would have been all over 1890s Instagram.

And thus aided and abetted by its placing in Liberty's, that contemporary cultural conditioner, and through its promotion via the SHIA and its network of well-to-do, culturally interested, socially fashionable, individuals, demand for Kirkness's chairs grew and grew. And grew.15

And became "the industry".

Here isn't the time nor place for a detailed exploration of the development of Kirkness's business, although that is very much needed, save to note that the Orkney Chair industry Sheriff Thoms and the SHIA helped create was largely David Kirkness along with a small army of home-workers weaving the backs for the four models he supplied: a hooded chair, a hoodless Gentleman's chair, a hoodless, and slightly smaller, Lady's chair and a child's chair, and that with a choice of either a wooden seat or a rush seat.16 And thus David Kirkness very much formalised the presentation and visual identity of the Orkney Chair; before 1890, and while there may have been "archetypes", each and every Orcadian would have realised their own version based on a combination of available materials and skill. Post-1890 the Orkney Chair was Kirkness's model, and thus while he may not have invented the straw-backed Orkney Chair, he very much came to define it.17

And to note that between 1890 and his death in 1936 David Kirkness produced some 14,000 chairs,18 an average of a little over 300 per annum, throughout the first years of the 1910s annual production running at some 400+.19 Which may not sound many, but not only was he a relatively small operation, nor only do we know many a contemporary "popular" chair design that would be delighted to sell 400 a year, but Kirkness operated not only before the internet, but almost before the postal service. And from Orkney. Even today inclement weather can briefly leave the islands isolated, back then more regularly, and longer, so. What he achieved wasn't easy.

And to note that while Liberty's remained over the decades an important customer, something underscored by the fact they had their own price list and variants20, other furniture/department stores throughout the UK also regularly placed orders with Kirkness. In addition, and beyond the numerous orders that came through the SHIA, Kirkness supplied chairs to customers as far afield as India, Canada, America, Australia & Neptune. Or at least the HMS Neptune; Commodore Boothby ordering in 1912 a Gentleman's Chair with a rush seat, to be delivered, unpacked, to Scapa Pier where the HMS Neptune was then anchored. Just one of a number of chairs Kirkness delivered to naval vessels anchored at Scapa.21 Not illogically, early 20th century naval ships being even draughtier than Orkney crofts.

And to note that despite the commercial success of the chair, a success based on the sort of fashionable associations that enable an easy marketing, there appears to have been no sustained attempt to copy it, to, as it were, jump on the bandwagon. That whereas, for example, Harris Tweed was copied and produced elsewhere in the UK until such was declared illegal, we can find no indication that such was attempted with the Orkney straw-backed chair.

Or at least not in the UK.

Over in Holland, now that's a different story.

As previously noted in context of the exhibition Art Nouveau in Nederland at The Gemeentemuseum, Den Haag; in 1898 John Uiterwijk and Chris Wegerif established the gallery/shop Arts and Crafts in Den Haag, an institution informed by both Siegfried Bing’s Maison de l’Art Nouveau in Paris and also Liberty's, and which was an important protagonist in the development of Art Nouveau in the Netherlands, for all in context of the batik work that stands so singularly in the Dutch expression, dialect, of Art Nouveau.

And as Annette Carruthers very nicely dissects, also introduced the Orkney Chair to the Netherlands.22 Or the Transvaal Chair as it was apparently known. For reasons lost in the mists of time. However, and as previously noted, the late 19th/early 20th centuries were a period of rising Dutch nationalism and Wegerif and Uiterwijk's associations with Liberty's and thus the English adversary, and also with Henry van de Velde and his dangerous “modern Belgian curvatures”, made Arts and Crafts all too open to accusations of being unDutch, and so choosing a more Dutch, if every bit as foreign, exotic and romanticised, name, arguably a name associated with romanticised ideas of Dutch nationalism, could have appeared advantageous.

According to Carruthers, Wegerif and/or Uiterwijk probably saw an Orkney Chair in Liberty's, may have bought one there, may have just sketched it; but certainly copied the basic idea, if in a slightly varied formal expression, and range of varieties, including a two seater bench and a corner bench unit. Yet whereas they may have copied the idea, their Transvaal Chair couldn't reproduce the commercial success of Kirkness's Orkney Chair; a lack of success, arguably, largely, primarily, related to the fact Arts and Crafts closed in 1904 and thus the lack of a real opportunity to establish a market. Yet despite the lack of success Chris Wegerif clearly remained a fan, a 1919 photo of the library of his 1915 Villa Kamp Links in Apeldoorn clearly shows an example of, we're claiming, a Kirkness Orkney Chair.

The Orkney Chair's short Dutch sojourn is however not any less interesting on account of its lack of commercial success, not least because of the reflections it allows on the use of geographical definers in product marketing, was "Transvaal" simply unconvincing to early 20th century Dutch consumers? And can one simply change such associations, and if one can what does that teach us? But for all the Orkney Chair's short Dutch sojourn is interesting on account of the differentiated understandings of the straw-backed Orkney Chair it enables.

David Kirkness died on October 4th 1936, aged 81, and with the enforced restrictions of the Second World War, no-one thinking to include the straw-backed Orkney Chair in the War-time Government's Utility Furniture Scheme, and, not unimportantly, altering priorities in society on account of the War, the production of the Orkney Chair, briefly, ceased. Restarting in the 1950s, albeit without the support of the SHIA, Liberty's or much in the way of any popular, tangible, Arts and Crafts/Art Nouveau sensibilities. And thus at a much lower, and low-key, level.

Today there are four commercial Orkney Chair makers on the Isles, or more accurately in Kirkwall, two of, let's say, an older generation, two of a younger, and thus the "industry" Sheriff Thoms sought to "do good to" is arguably as it was in March 1890.

Has just been through a few lives, through a few twists of the helix, in the intervening century and a bit

But for all, the straw-backed Orkney Chair remains. And isn't just produced commercially but also non-commercially, on a hobby basis. And isn't just produced on a commercial and non-commercial basis, but repaired; a well-made frame being, as Kirkness himself noted "practically unbreakable"23, the backs in contrast liable to become tired over the decades. Are however readily replaceable.24

And a readily replaceability which is not only inherent and implicit in the design, but very succinctly highlights the disparity between the romanticised understanding of the straw-backed Orkney Chair, and more pragmatic understandings

Annette Carruthers opines, and while acknowledging that more work needs to be done on unravelling the early years, the Orkney Chair "was a largely 'invented tradition'" à la Eric Hobsbawm and Terence Ranger25, which doesn't mean invented invented but, if one will, forced into an externally defined corset. We can't go fully along with that position, but can partially, for all if we focus on an invented tradition as an "attempt to establish continuity with a suitable historic past".26

Which was what Sheriff Thoms and the Scottish Home Industries Association did.

And which the straw-backed chair is.

In Orkney.

And where it existed without any inherent association with any given identity. That is applied externally, for example by the exiled Orcadians and/or tourists we presumed bought Kirkness's chairs pre-1890.

And such an association won through personal experience and/or memory, however idealised and simplified that in many cases may be, Carruthers speaks of nostalgia, is clearly very different from an abstract, contextless, projected association one is informed one should make with an object, any object, on account of a claimed cultural authenticity, a claimed "continuity with a suitable historic past". Such cannot be the basis for assigning value to any item of furniture. Or anything.

We know, we know, we also read advertising. And newspapers.

Limitations of space mean we can't go into a full discussion here on the term "value" in context of a furniture; however, and summarising as we must, for us the value of an item of furniture comes from the inherent properties of the work and from use.

The former can most conveniently be reduced to an honesty, to several honesties, including, amongst others, an honesty of development, an honesty of construction, an honesty of materials, an honesty of expression, an honesty of function.

And which we'd argue the straw-backed Orkney Chair unquestionably possesses. You don't have to know anything about the work to know its going to treat you well and not deceive you. Be it the almost naively simple construction system, the openness with which it presents itself or the clarity with which it explains itself, it is an item that invites dialogue. Yes, the form as understood today is and was largely defined by the demands of the market Kirkness was selling in to, but it existed more or less in that form before the market, before the industry.27

But more importantly, as an object the straw-backed Orkney Chair isn't its formal expression. But its straw-back. A straw back that is not only unyieldingly honest, but which made sense then and makes sense now; made and makes senses not just as a low-tech, low-cost, local material, but from perspectives of comfort, insulation, repairability, usability, tactility, and as a material which over time will develop, as we all do, the patina of lives known.

And thus a manifestation of that other value in furniture, that personal association that develops with an object of furniture. That which can't exist before you own an object, or certainly not before you have personal experience of an object, but which becomes the individual identification. Becomes the reason you want continue owning that object. The value of the object. To you. As opposed to the collective value in a work's inherent properties.

And individual and collective values that should never be confused with a projected symbolism. But all too often are.

In addition, placing the value of any object of vernacular furniture on a symbolism prevents it evolving.

Eric Hobsbawm differentiates between a custom and a tradition: the later defined by its "invariance", the former having "the double function of motor and fly-wheel" and of its being permitted to evolve within constraints.28

Vernacular furniture is all too often taken to be a tradition, must however be considered a custom: an inherent close relationship to developments in and realities of culture, society, technology, et al is not only the reason for the genesis of an item of vernacular furniture, but the reason for their evolution and development. The path the straw-backed Orkney Chair has taken from the upturned basket to the wooden framed chair, and, yes, we buy into that path, albeit with conditions29, but we buy into it, is a path, we'd argue, that must be understood as one associated with the development of the realities of daily life in Orkney since the 17th century: as the economic situation of the islands developed, as new technology arrived, as people moved to and from the islands, as communities grew and shrank, as professional trades established themselves, as wood became marginally more readily available than it had been, etc, etc, etc.

And thus the Kirkness Orkney Chair can't be considered the end of the story, rather marks a particular moment in the (hi)story of the Orkney Isles, in the (hi)story of the straw-backed Orkney Chair, in the history of the straw back; and that straw back must continue to evolve and develop, must be enabled to meet contemporary needs, otherwise it risks becoming irrelevant.

Something arguably Chris Wegerif and John Uiterwijk were the first to explore. Through taking the straw-backed Orkney Chair to a new country, a new culture, a new context, they were able to re-imagine and re-define the object; through removing it from the corset of cultural and historic associations and symbolism the SHIA had forced in into, they allowed it to once again breath freely and for all allowed the straw back to express itself, to understand itself, anew.30

And which, pleasingly, can be sensed today amongst contemporary makers. Not that we'd argue all the contemporary expressions of the straw-backed Orkney Chair are necessarily courteous to the straw back, they're not. And some are. But for all one senses that while maintaining the Kirkness model, and correctly so, it is a joyously open, responsive, attentive and articulate object, and just because an object evolves doesn't mean the existing must cede, far from it, good is good and remains good; but one senses that the straw-backed chair today is increasingly being understood as the tightly woven straw back, and thus, if one so will, as it was understood up until 1890.

Before it became an industry.

Before it became endowed with romantic symbolism.

Before it became a definitive representation of native Orcadian tradition rather than an expression of an Orcadian custom.

Before it became distracted by global fame.

A global fame the straw-backed Orkney Chair very much deserves.

But it no way needs.

It's happy and content by the fire in a draughty croft. And in itself.

Given the very specific, non-global, locality of straw-backed Orkney Chair production, and for all supply, the four (as at time of writing) contemporary makers are (in no particular order):

And in the interests of completion, the soundtrack to the writing of this post was provided by Orcadian composer Erland Cooper.

1For all the talk of "Orkney Chairs" it is important to note that similar objects are also found further north on the Shetland Isles. We no know, and as far we understand no-one know, the relationship between the two, if, as with Darwin's finches, they developed independently or if they are inter-related, whereby the common consensus that the Orkney variety arose on North Ronaldsay, and thus the point of Orkney closest to Shetland is perhaps not irrelevant. And, yes, woven wicker furniture is near universal. But requires trees. Big hedges. The focus here on Orkney is on account of the late 19th/early 20th century popularisation and derived associations.

2Walter Traill Dennison, Manufacture of Straw Articles in Orkney in M.M. Charleson [Ed.] Orcadian papers: being selections from the Proceedings of the Orkney Natural History Society, from 1887 to 1904, Stromness, 1905 page 32ff Exact date of the paper is unknown, however, Walter Traill Dennison died in 1894, and thus his paper may have been presented before the 1890 Edinburgh exhibition but was almost certainly presented before Kirkness's chair became the phenomenon it did. And which thus, for us, tends to imply the wood/straw mix did arise organically and naturally in Orkney. Although Walter Traill Dennison was a famed collector of Orcadian fairytales and legends.... (Available via https://doi.org/10.5962/bhl.title.128557 Accessed 16.11.2020)

3ibid

4There are trees in Orkney, the myth that Orkney is tree free is just that. A myth. Its Vikings, Puffins and an intangible but impenetrable headwind are however very true.

5The Vikings clearly made their boats from wood, but not only would a lot of them would have built in Norway but trees were apparently, a little, more plentiful in Orkney in millenia past. And wooden boats have also used by non-Vikings for centuries. And a great many other long-standing Orcadian objects were wooden. But wood was a rare material. And driftwood remains an important source, whereby one shouldn't confuse driftwood with the odd plank or branch, regularly whole trunks, large logs wash up, often en masse having fallen from the timber ships that criss cross the Atlantic.

6James Omond, Orkney Eighty Years Ago (with special reference to Evie), The Orcadian, Kirkwall, 1911 page 41

7We're not completely convinced by the 18th century argument. It is largely based on Traill Dennison's paper, (see note 2 above, page 42), but strikes us as being a little early for the combined wooden/straw version that he describes, not least for the need to drill small holes through the side strips to attach the back. Early 19th century makes more sense to us, and so for us the question is if Traill Dennison's "first half of the eighteenth century" is a misprint or a rogue line in the original text. If he meant, potentially said at the paper's presentation, nineteenth century or 1800s?

8Letter from George Hunter MacThomas Thoms dated 27th March 1890. Kirkness Collection, Orkney Archive, Kirkwall.

9Janette A. Park, Simmans, Sookans and Straw Backed Chairs, Orkney Arts, Museum and Heritage, Kirkwall, 2017

10The Observer, May 4th 1890, page 2

11Sarah Kirby, ‘Sweet Music Discoursed in Distant Concert Halls’: The Telephone Kiosk at the 1890 Edinburgh International Exhibition, Context, Nr. 44, Winter 2019, pages 51–9.

12Stana Nenadic and Sally Tuckett, Artisans and aristocrats in nineteenth-century Scotland, Scottish Historical Review, vol. 95, no. 2, 2016, pp. 203-229

13ibid

14It needn't be explained that in the 19th century only the very wealthy could enjoy such pleasures, today's faux reality is much more democratic in its availability. If no less faux.

15It would be unfair to claim that all who bought a Kirkness chair did so on account of buying into a projected heritage and implied identity. Many invariably appreciated the work for what it is not what it represented. Especially as one moves through the 1920s and 1930s, further away from an Arts and Crafts influence, and, arguably, as an increasing number of Orcadians left the isles and ordered chairs from their new homes. But, we'd argue, the reason it established itself and became such a "thing", was the symbolism, associations and romanticism.

16The popular understanding of Kirkness's four versions is based on an undated price list in the Kirkness Collection at Orkney Archive; however, a photo of Kirkness's chairs at the 1909 Internationale Volkskunst-Ausstellung in Berlin tends to indicate that either the Lady's chair was tiny, or there was a smaller child and a larger child version. Or at least such were exhibited. If described as being "Chairs from England" !!! The Berlin presentation was also organised by the SHIA. And very much focussed on Harris Tweed, see Führer, Internationale Volkskunst-Ausstellung, Deutscher Lyceum-Club Berlin, 1909 page 41ff (Available via http://resolver.iai.spk-berlin.de/IAI0000609000000000 accessed 16.11.2020)

17A particularly interesting aspect is the drawer. Or non-drawer. In his paper Traill Dennison notes "the seat box generally contained a drawer". Yet when the second chair Sheriff Thoms requested arrived with a drawer he was indignant, "a drawer under the seat gives it altogether the appearance of a night stool & makes it inappropriate as a drawing room chair ... you will never get customers at the Exhibition for your night stools." Thus a second without drawer was dispatched. And thus, in order to entice middle and upper class customers, an object deemed suitable for the late 19th century upper/middle class drawing room was demanded. But which could be presented, marketed, as being authentic, traditional and as would have been found for generations in an Orkney croft. Which clear can't be anything but a contradiction. And a falsehood. And while objects with and without drawers would have been made pre-1890, each maker creating according to their talents and materials, and Kirkness continued making objects with drawers post-1890, as far as Liberty's et al were concerned the Orkney Chair had no drawer. And thus a very specific, and far from definitive, understanding of the Orkney Chair. And a drawer adds an extra functionality. Makes sense. In addition its interesting that Thoms wanted an unpainted chair sent, presumably so that he could have painted in Edinburgh in a suitable fashionable tone. One that was unlikley to be available in Orkney. See letters from Sheriff Thoms in Kirkness Collection, Orkney Archive, Kirkwall.

18"Noted Craftsman Passes Away" Westray Man's Busy Commercial Career, David Kirkness Obituary, The Orcadian, Thursday October 8th 1936

19see, Order Book 1909 - 1914 Kirkness Collection, Orkney Archive, Kirkwall. This is the only known Kirkness order book, thus underscoring part of the problem of fully understanding the nature and development of the Kirkness business. Including attempting to deduce why customers bought.

20Undated price list in Kirkness Collection, Orkney Archive

21see, Order book 1909 - 1914 Kirkness Collection, Orkney Archive, Kirkwall.

22Annette Carruthers, The Social Rise of the Orkney Chair, Journal of Design History, Vol. 22, No. 1, 2009, pages 27-45

23Undated price list in Kirkness Collection, Orkney Archive. Also notes that "the finished article invariably brings repeat orders" and is generally a very nice piece of marketing. Indicating that Kirkness was well aware of how to sell.

24Whereby changes in the nature of Orkney agriculture, the shifting from small scale to large scale, means that the black oats that are preferentially used in Orkney Chair production, but are lower yielding, are becoming ever rarer on the islands. Necessitating makers to enter into agreements with farmers. And also contemporary mechanically harvested oats are no use for chair backs, you need undamaged stalks. And thus a very nice illustration of how developments in one area of culture, society, technology et al impact on others.

25Annette Carruthers, The Social Rise of the Orkney Chair, Journal of Design History, Vol. 22, No. 1, 2009, page 41

26Eric Hobsbawm, Introduction: Inventing Traditions, in Eric Hobsbawm and Terence Ranger [Eds], The Invention of Tradition, Cambridge University Press, 2012 pages 1- 14

27In terms of the "demands of the market he was selling into" see note 16 above. In terms of form, Traill Dennison's description of the North Ronaldsay chair is very similar to that which Kirkness produced, and so if we assume that Traill Dennison's description preceded the 1890 exhibition then Kirkness was, presumably, making chairs pre-1890 akin to those Traill Dennison implies arose in the early 18th century. But clearly individual Orcadians making their own would have followed their own design.

28Eric Hobsbawm, Introduction: Inventing Traditions, in Eric Hobsbawm and Terence Ranger [Eds], The Invention of Tradition, Cambridge University Press, 2012 page 2

29see note 7 above

30Interesting here would be to know why Wegerif and Uiterwijk took on the Orkney Chair, if they bought into the symbolism, or if they were appreciative of the design, appreciative of the woven straw back, and thought that was something they would like to work with, seek to develop.