Furnishing Brexit? Or, Reflections on the Utility Furniture Scheme…

As all familiar with the peculiar and idiosyncratic method by which these dispatches are produced will appreciate, come March 30th 2019 there will be a few fundamental changes, as the smow blog team are forced to abandon our familiar home on the internet and create a new one for ourselves in the analogue wastelands of the (dis)United Kingdoms.

And as Brexit’s unregulated shadow casts itself ever deeper, indelibly, suffocatingly, over the smow blog office, our thoughts turn, somewhat inevitably, to the furniture we may find ourselves engaging with in an all too palpable future.

Will we even have furniture? Or will be forced to refer to the neolithic tribes of Skara Brae and their intuitive and innovative use of stone?

Possibly.

However it may not come that far, for, and despite whatever other deficits and callowness it has, Whitehall does have experience in securing the supply of furniture in times of national emergency: the Utility Furniture Scheme of the 1940s…….

As we’ve oft noted in the pages, developments in context of furniture design are inextricably linked to evolutions in cultural, social, political, economic and/or technical realities. And as a general rule are gradual; but occasionally, very, very occasionally, they are much more sudden.

Instigated, enforced, by the realities of the Second World War, the Utility Furniture Scheme is one of those rare examples of a sudden change, and one that can, possibly, prove instructive for the coming months and years; or as Pinch and Reimer opine, “War may represent an extreme event, but nevertheless its effects are revealing.”1 Brexit is also an extreme event, and one we can, arguably, best prepare for through analysing historic extreme events.

Although formally in place between 1943 and 1948, the Utility Furniture Scheme can be considered much more as a process which began in 1939, ended in 1953, and that, at least initially, was primarily concerned with ensuring the supply of timber for the war effort: according to MacGregor during the century between 1850 and 1950 “the outstanding feature of the United Kingdom timber requirements is the very heavy reliance on imports”, and that between the two world wars “about 96 per cent of total [UK timber] requirements were regularly imported”2, Mills additionally noting that before the war some 56% of the UK’s hardwood imports were from Europe.3 A (general) reliance on Europe Great Britain hasn’t lost, and a reliance whose disruption, then as now, must, by necessity, cause problems.

Following the issuing of the general Control of Timber Order in September 1939, a series of further orders relating specifically to furniture were issued, and which for all set ever tighter limits on the amount of wood available for furniture production. A situation intensified by the fact that, as Clive Edwards notes, whereas as in 1939 there were some 2,000 factories in the United Kingdom “making wooden furniture, bedding, and fabric-based objects. By 1943, only 200 remained unengaged in some form of war work.”4 Which doesn’t mean that all of the other 1,800 stopped producing furniture completely, does mean that in those five years Britain lost a large part of both its furniture production material and capacity.

Furniture remained however a necessity. On the one hand daily life continued, more or less, apace, but also to replace that lost in the Luftwaffe‘s regular bombing raids, a situation that became particularly acute as such raids intensified in late 1940/early 1941; a period where timber shortages became ever more extreme: in May 1940 “the furniture industry was getting only fifteen percent of its pre-war timber supplies”5, supplies which, or at least for civilian furniture, completely dried up in July of that year6. And thus a necessity and shortage which, inevitably, combined to advance a climate of profiteering and exploitation. Times of national emergency not necessarily being all about social cohesion and unity, despite what the flag wavers may have you believe.

A living room display as part of an exhibition of Utility furniture at the Building Centre, London in 1942 (Photo © IWM (D 11053) )

In an attempt to both prevent the profiteering and ensure sufficient, affordable, furniture was available to those who needed it, the Government introduced price controls on both new and second-hand furniture in June 1940, and in February 1941 the Ministry of Health launched the Standard Emergency Furniture programme, a collection of simple wooden furniture objects whose production and distribution was controlled by the government and where, “It was intended that this furniture would be loaned to claimants who could then either return the furniture or purchase it at a reasonable price”7 And which thus, and aside from any Brexit considerations, sounds like a social furnishing concept well worth considering today.

As the intensity of the war increased, including, as David Peck notes8, a rise in, and increasing efficiency of, German submarine attacks on the Atlantic Fleet and the consequent reduction in supplies, including chlorinate chicken timber, reaching the UK from the Americas, restrictions on the supply of wood for furniture become ever stricter, and in November 1941 were limited to those manufacturers producing from a list of 22 prescribed items. The situation however continued to escalate, not least in early 1942 when the plywood used for Standard Emergency Furniture was assigned exclusively for the production of aircraft,9 leading in May 1942 to questions being raised in the House of Commons concerning possible arrangements for the supply of good, affordable furniture10; before in July 1942 the Utility Furniture Scheme was formally announced.

Run under the auspices of the Utility Furniture Advisory Committee the Utility Furniture Scheme sought to realise “furniture of good sound construction in simple but agreeable designs for sale at reasonable prices and ensuring the maximum of economy of raw materials and labour”.11

Following a brief commissioning and consultation process, January 1943 saw the publication of the first Utility Furniture catalogue, the majority of the objects designed by Edwin Clinch, in-house designer with High Wycombe based manufacturer Goodearl Brothers, and Herbert Cutler from Wycombe Technical Institute, and supplemented by existing designs12, including an 1877 Windsor chair design from High Wycombe based manufacturer Ercol; and a collection which as of January 1943 represented the only furniture objects manufacturers were allowed to produce, and whose distribution, sale and price was equally firmly under central Government control. A situation that remained the case until November 1948 and the introduction of the so-called Freedom of Design legislation which brought an end to full state control and sought to “maintain the standard of quality of utility furniture, but will give manufacturers freedom to make it to their own designs, and by the methods which they can most efficiently employ.”13; albeit with the proviso that those objects not conforming to the still existent Utility regulations were subject to a Purchase Tax of 33⅓ percent, while Utility conform objects remained untaxed. And extremely popular, the President of the Board of Trade noting in 1950 that “Estimates indicate that Utility furniture accounted for about 85 per cent. by value of total furniture production in both years [1949 & 1950]”14

Despite such success, the Utility Furniture Scheme was formally wound up on January 21st 195315 and furniture manufacturers were once again free to produce and sell what they wanted how they wanted.

An Ercol Windsor Chair, a design from 1877, employed in the 1943 Utility Furniture Scheme, still on sale today…. and therefore a likely candidate for any Utility 2.0

Described, very fittingly, by Judy Attfield as “design by dictate”16, the very strict regulations, and background of restricted material availability and limited production capacity, mean the initial Utility Furniture Scheme objects are/were a thoroughly unremarkable mix of basic wooden chairs, wardrobes, chests of drawers, kitchen cabinets et al; or at least appear so to our 21st century eyes, in 1943 they represented a fundamental shift in the (hi)story of British furniture design and manufacture.

Pre-war furniture in Britain was still largely, and generalising to the point of inaccuracy, of the classic, representative, faux, type, complete with cabriole legs, Queen Anne and Jacobean silhouettes and ornate decoration; in addition manufacturers tended to offer a limitless choice of variations on a particular item, regularly offering retailers their own exclusive versions of particular models, each piece individually made to order17, a thus a system of manufacture that although largely relying on pre-produced components, was far removed from mass, serial, production. Or as a post-War UK Government report on the state of the pre-War furniture industry noted, “…except in the largest firms, it is true to say that the industry still bears strong signs of its handicraft origins”, that, “Factories are generally old-fashioned and expansion has been achieved by adding extensions to original buildings rather than designing new factories and lay-outs to suit the new techniques of production” and that the industry was largely made up of small operators with few staff and little capital.18 And was largely, though not exclusively, based around North/East London and environs, for all High Wycombe, one of England’s traditional centres of furniture production, something underscored by the city’s role in the compiling of the first Utility Furniture catalogue.

The war, and for all the Utility Furniture Scheme, changed all that.

On the one hand the need to produce quickly, and to much tighter margins and with fewer workers, than had previously been the case, led to an increased reliance on mass, machine, production; a state of affairs that, as Edwards notes,19 was aided and abetted by the fact that many of the larger furniture factories spent the war manufacturing aircraft components, where there is a need for a precision far above that of furniture, for a machine precision, and which led, (more or less) automatically, to an increased post-War reliance on mass, machine, production. In addition their work on contemporary aircraft production exposed many of the manufacturers to new materials and processes, including synthetic glues, sophisticated plywood moulding or the use of aluminium20; the later becoming particularly important post-War as manufacturers were actively encouraged by the Government to use recycled aluminium as an alternative to the, still relatively scarce, wood.

Among the more interesting experiments with aluminium being Ernest Race’s Utility conform, and therefore widely affordable, BA 3 aluminium chair, a work which in 1954 was awarded a Gold Medal at the Milan Triennale; the Framed Furniture system by, amongst others, the then Board of Trade’s Director of Furniture Production Arthur Walsh and the designer Gordon Russell, and which foresaw objects created from/by an extruded aluminium skeleton which created “frames arranged to house panels of any appropriate material or construction”21, and which thereby used the aluminium as both a structural and decorative feature, while reducing the amount of wood needed for storage and shelving units; and Clive Latimer’s Plymet collection for Heal’s of London, Plymet emerging from war time advances in aircraft production technology, and which was described as representing “A new technique for bonding metal to wood …The aluminium sheet is veneered on both sides to make a metal-cored plywood”, and thus a material where, “the best qualities of wood are combined with those of metal”22

A unit constructed according to the Framed Furniture system developed by Arthur Walsh, Arthur Kershaw, Gordon Russell and George Cleaver in context of the Utility Furniture Scheme (image © Victoria and Albert Museum, London)

The logistic realities of manufacturing in war time also led to an increased regionalisation of furniture production in the UK. Manufacturers needed a Board of Trade license to produce Utility furniture and through the distribution, and, when necessity dictated, re-distribution of the licenses, the Board of Trade was able to ensure furniture was produced close to where it was needed, and in areas where the requisite numbers of available workers could be guaranteed. Consequently, whereas before the war neigh on half the UK’s furniture manufacturers were to be found in London/High Wycombe, during the Utility years that dropped to but a third, with what Reimer and Pinch refer to as the establishment of “notable clusters of activity along a Leeds-Manchester-Liverpool axis, in Birmingham, Bristol and in central Scotland”.23 And thus centres of not only high population, but industry; industry who may never have made furniture, but had enough basic competence to start.

Logistic considerations also saw, when less directly, a change in the role of the furniture retailer; previously the retailers had to a large, decisive?, degree dictated what was produced, with Utility furniture not only did the Board of Trade decide, but the realities of the production and distribution arrangements meant that retailers rarely had display stock, customers as a rule ordering from a catalogue, the retailers role being little more than advising how many coupons were needed for specific items that week and arranging the delivery. Had the internet existed in 1943 there would have been no need for physical furniture stores. Should the internet exist in 2019 Britain, it will, we would imagine, replace the coupons and catalogues of yore.

While in terms of formal aspects the Utility regulations were not only so conceived so as to reduce waste to a minimum, to optimise the use of available materials, but were also based around using thinner wood than manufacturers traditionally employed and the use of simpler joints and more reduced, less involved, construction systems, and thus regulations which changed the formal aesthetics of furniture, created furniture that was visually much lighter and more accessible than a majority of the pre-War standards. And regulations which following the introduction of Freedom of Design in 1948 enforced a degree of creativity on the more progressive manufactures and designers. Something they rose to. Among the more interesting examples being the development by Christopher Heal of a modular furniture series based on the Utility regulations, something, as he notes, Utility objects “were never meant to be”24, but which also is just the most satisfying and deliciously logical extension of the Utility principles, the furniture realities of the period were crying out for modular solutions. And, we’d argue, as we always do, still are.

In addition Utility rules banned all ornamentation, and thereby forced manufacturers to produce, more or less, according to the ideals of the International Modernists; something relatively new, something that had been known in pre-War Britain, but hadn’t become naturally established, and something Judy Attfield implies was seen very critically by conservative factions of the then British furniture industry who saw the Utility objects as, “degraded adaptations driven by state-imposed strategy to force the industry into concentrated mass production”25

And certainly many of those who had helped instigate and guide the Utility Furniture Scheme, including the likes of the designer Gordon Russell, author and journalist John Gloag or Isokon founder Jack Pritchard, saw the Utility scheme very much as a vehicle via which to introduce new, Modernist, principles and practices into UK furniture design. Such desires weren’t the reason for the formal aesthetics of the Utility furniture, that owed much more to Form Follows Economic Necessity than any deep ideological conviction; however, whereas firms such as Isokon with their moulded plywood or Oldbury based PEL with their steel tubing, had won industry acclaim in the 1930s, but never a mass market, Utility furniture was considered an unconventional, backdoor to introducing more progressive furniture to UK consumers , and in 1946 Jack Pritchard was very positive, noting, that “in spite of its limitations of choice, we believe that the utility furniture scheme has done much to accustom a wider public to a better standard of design.”26

One could argue that exactly because of its limitations the Utility Furniture Scheme did much to accustom the UK public to new understandings of furniture design.

The more important question is, if they found such new understandings “better” or if they preferred the heavy, ornamented pre-War standards?

A question which to answer involves a deeper exploration of the debate between the traditionalist and reformist tendencies, a debate which had begun in the 1930s and continued into the 1950s.

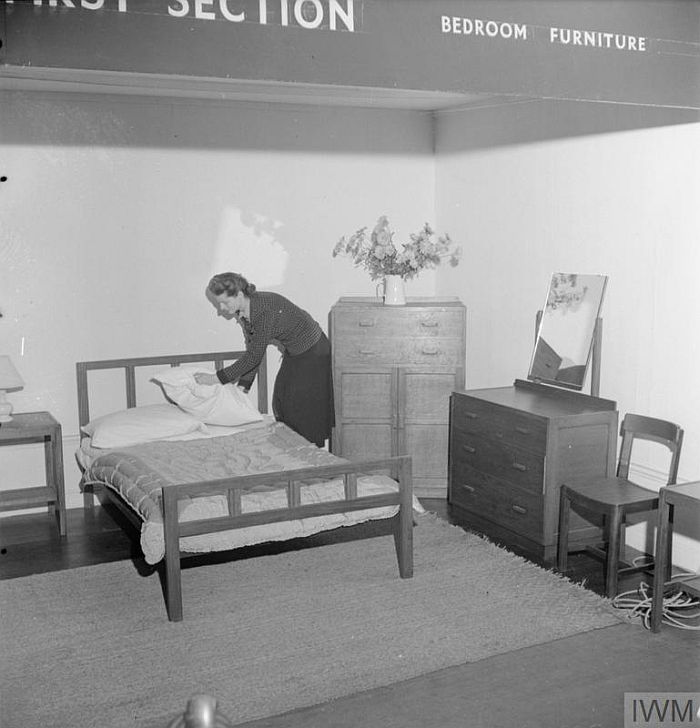

A Utility bedroom, part of a display of Utility furniture at the Building Centre, London in 1942 (Image © IWM (D 11051) )

And a debate for another day.

For fascinating, and important, as it is, here our focus can only, and must only, be the Utility Furniture Scheme itself and for all what we can learn from it as we approach XE Day.

Despite universal agreement that the Utility Furniture Scheme successfully ensured furniture supplies during the war years, hard statistics are hard to come by. Amongst the few that did come our way are production figures for 1948, the last year in which the scheme was fully in force, the last year of furniture rationing, and a year when many of the problems that had caused Utility’s creation were no longer (as) relevant, where one could thus expect demand to be less than in the scheme’s early days. Despite that, according to the Board of Trade, in 1948, and amongst other objects, some 2,330,000 Utility chairs (dining and kitchen), 996,000 Utility bedsteads (metal and wood) and 67,000 Utility kitchen tables were produced, and that “the estimated value of utility furniture production in 1948 was £60,000,000 (at manufacturers” prices)”27 Or some £1.8 billion in today’s terms.

And thereby figures which, and in soberly considered conjunction with more circumstantial evidence, for all the regular complaints of long waiting times and production bottlenecks, tends to imply that it is questionable whether war time furniture supply could have been guaranteed outwith the scheme. And thereby must be considered, as Harriet Dover does, that it represents “one of the most notable successes of the Home Front campaign”,28 and thus one of the most notable success in context of ensuring supply of furniture during a period of national emergency.

That it was can, arguably, be reduced to one central conclusion: trade shouldn’t be a government’s guiding principle, but supply. If supply can be ensured through trade, so much the better, if not, responsibility must be taken from that trade. The needs, desires, aspirations of the populace is primary, not those of industry.

In addition there are, for us, two further important understandings from such reflections on the necessities of an “extreme event” .

Firstly, what one sees with the Utility Furniture Scheme is that real innovation came post-War, when the end of hostilities saw the list of furniture to be produced replaced by regulations as to how furniture was to be produced. Limitations which still allowed for a strong degree of centralised control over raw material supply, product distribution, price and therefore ensured, or at least ensured as far as was possible, that all who needed it had access to “furniture of good sound construction in simple but agreeable designs for sale at reasonable prices”; yet also allowed for, and led to, individual innovation, creativity and authorship of a very high standard, and thus limitations which helped advance furniture design. Advances which otherwise may not have occurred.

And secondly, and as Pinch and Reimer argue,29 the fact that the Utility Furniture Scheme not only relied on localised production but also compelled consumers to buy through a local supplier, meant the system had an inherent sustainability; it broke, or perhaps better put, seriously disrupted, the central production/global distribution model and was, if you will, a form of lo-cost, lo-tech, local production: which as older readers will know is something we’re not only very keen on, but believe is, must be, the future of the furniture industry.

If considerations we can’t get overly excited about.

For much as those in 1930s Britain would have much preferred no war, Brexit is a larger scale intervention in our lives we could gladly do without; but if it must come, then there is at least the hope that, if properly managed, and once the hostilities are over, the privations, limitations and extremes of Brexit could, possibly, lead, compel, the British furniture industry and British furniture design to move in more future orientated directions, could force them to adopt future orientated technologies, future orientated practices, future orientated structures and to develop future orientated objects.

If properly managed……..

…..and so, yeah, on the evidence of the past two and a bit years, if anyone wants us, we’ll be on the beach collecting large stones….

The smow blog office as from April 2019….. (with apologies to the former neolithic community at Skara Brae, Orkney)

1. Philip Pinch and Suzanne Reimer, Nationalising local sustainability: lessons from the British wartime Utility furniture scheme, Geoforum, Volume 65, October 2015

2. J. J. MacGregor, The Sources and Nature of Statistical Information in Special Fields of Statistics: Timber Statistics, Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series A (General), Vol. 116, No. 3, 1953

3. Jon Mills, The 1943 Utility Furniture Catalogue With an Explanation of Britain’s Second World War Utility Furniture Scheme, Sabrestorm Publishing, Seveneoaks, 2008

4. Clive Edwards, Technology Transfer and the British Furniture Making Industry, 1945-1955, Comparative Technology Transfer and Society, Volume 2, Number 1, April 2004

5. W. K. Hancock & M. M. Gowing, British War Economy, HMSO, London 1949

6. Alastair Best & Mark Brutton, Utility in Design, Nr 309, September 1974, Design Council, London

7. Matthew Denney, Utility Furniture and the Myth of Utility 1943-1948, reprinted in Grace Lees-Maffei & Rebecca Houze (eds) The Design History Reader, Berg, 2010

8. David Peck, Prometheus Missing. Critical Materials and Product Design, PhD Thesis, Delft University of Technology, Delft, the Netherlands 2016

9. Utility Furniture and Fashion 1941 – 1951 Geffrye Museum London 24 september – 29 December 1974, Inner London Education Authority.

10. Matthew Denney, Utility Furniture and the Myth of Utility 1943-1948, reprinted in Grace Lees-Maffei & Rebecca Houze (eds) The Design History Reader, Berg, 2010

11. Board of Trade Document 64/1897, quoted in Matthew Denney, Utility Furniture and the Myth of Utility 1943-1948, reprinted in Grace Lees-Maffei & Rebecca Houze (eds) The Design History Reader, Berg, 2010

12. Alastair Best & Mark Brutton, Utility in Design, Nr 309, September 1974, Design Council, London

13. Hansard 22 November 1948 Vol 458 cc869-71, https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/commons/1948/nov/22/furniture-controls-relaxation Accessed 12.03.2019

14. Hansard 01 December 1950 vol 481 cc182-6W https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/written-answers/1950/dec/01/utility-goods-production-statistics Accessed 12.03.2019

15. Harriet Dover, Home Front Furniture. British Utility design 1941-1951

16. Judy Attfield, “Give ’em Something Dark and Heavy”: The Role of Design in the Material Culture of Popular British Furniture, 1939-1965, Journal of Design History, Vol. 9, No. 3, 1996

18. Board of Trade Working party reports: Furniture, HMSO London, 1946, quoted in Philip Pinch and Suzanne Reimer, Nationalising local sustainability: lessons from the British wartime Utility furniture scheme, Geoforum, Volume 65, October 2015

19. Clive Edwards, Technology Transfer and the British Furniture Making Industry, 1945-1955, Comparative Technology Transfer and Society, Volume 2, Number 1, April 2004

21. GB Patent Specification 632,618, Application Date Jan 8 1948 https://worldwide.espacenet.com/publicationDetails/originalDocument?CC=GB&NR=632618A&KC=A&FT=D&ND=3&date=19491128&DB=&locale=en_EP# Accessed 12.03.2019

22. Plymet Catalogue, Heal’s London, 1947, quoted in Clive Edwards, Technology Transfer and the British Furniture Making Industry, 1945-1955, Comparative Technology Transfer and Society, Volume 2, Number 1, April 2004

23. Suzanne Reimer and Philip Pinch, Geographies of the British government’s wartime Utility furniture scheme, 1940-1945, Journal of Historical Geography, Volume 39, January 2013

24. Alastair Best & Mark Brutton, Utility in Design, Nr 309, September 1974, Design Council, London

25. Judy Attfield, “Give ’em Something Dark and Heavy”: The Role of Design in the Material Culture of Popular British Furniture, 1939-1965, Journal of Design History, Vol. 9, No. 3, 1996

26. The Working Party Report on Furniture, The Board of Trade, HMSO, London, 1946 quoted in Daniel Moore, “A New Order is Being Created”: Domestic Modernism in 1930s Britain, Modernist Cultures, vol.11, no. 3, 2016

27. Hansard 16 March 1949 vol 462 cc195-7W, https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/written-answers/1949/mar/16/utility-production#S5CV0462P0_19490316_CWA_48 Accessed 12.03.2019

28. Harriet Dover, Home Front Furniture. British Utility design 1941-1951

29.Philip Pinch and Suzanne Reimer, Nationalising local sustainability: lessons from the British wartime Utility furniture scheme, Geoforum, Volume 65, October 2015

Tagged with: Brexit, CC41, furniture, United Kingdom, Utility, Utility furniture, War