Cleaning is a chore.

If only we could get through life without the necessity of dusting, sweeping, washing, polishing et al.......

With the project Cleaning against the Dictatorship of Efficiency Birgit Severin and Guillaume Neu-Rinaudo a.k.a. studio b severin explore cleaning, its rituals, contexts, symbolism, functions, psychology, and in doing so enable differentiated perspectives on both that ubiquitous chore and the necessity in the necessity of dusting, sweeping, washing, polishing et al............

As a project Cleaning against the Dictatorship of Efficiency has its origins in a trip Birgit and Guillaume made to Japan in 2017 and specifically a visit to Naito in Kyoto, a family business in the 7th generation specialising in the production of traditional cleaning tools, primarily brushes, and an experience which stimulated the designers in Guillaume and Birgit more than the tourists or consumers within them; for all the contrast between the skill, passion and time involved in creating cleaning tools via traditional craft methods from traditional materials and the banality of cleaning, the value of the object juxtaposed with the value of the action it is intended for. And the contradiction therein.

Or rather the contradiction inherent in context of a contemporary European view of the world. Seen through other eyes there is no contradiction. A disparate perspective that poses interesting questions.

And a stimulus and questioning Birgit and Guillaume were able to pursue and explore in 2019 in context of a three month residency at the Goethe Institut's Villa Kamogawa in Kyoto, a residency which saw them research cleaning in more detail: cleaning not just as an act, but for all the culture of cleaning in Japan, the rituals of cleaning in Japan, the functions of cleaning in Japan.

Research they continued on their return to Berlin during a 2020 residency at the feldfünf project space; a residency which enabled both reflections on that which they had observed, experienced and witnessed in Kyoto in context of Berlin, on the varying cultural and social relationships and understandings of cleaning in Japan and in Germany, and also allowed for a degree of experimentation with that which they had observed, experienced and witnessed in Kyoto in Berlin.

Research, reflections and experimentation which form the basis of the Cleaning against the Dictatorship of Efficiency showcase at feldfünf.

Or more accurately in feldfünf's expansive window.

A window on the project, if one so will.

A window on cleaning.

Window cleaning.

"Glass is the very symbol of transparency and non-attachment", writes Shoukei Matsumoto in his book A Monk's Guide to a Clean House and Mind, continuing that, "if your windows are cloudy or dusty, your mind will become cloudy as well."1

An understanding of window cleaning that helps one appreciate that while cleaning is a chore, it is also a metaphor. Certainly in Buddhist teaching.

And while it would be generalising to the point of lying to claim that all in Japan follow Buddhist teachings in context of cleaning, they obviously don't; understanding Buddhist teachings in context of cleaning is important to understanding the development, cultural relevance and function of cleaning in Japan.

And thus, logically, served as one of the foci for Guillaume and Birgit's research in Kyoto, including Matsumoto's book whose numerous examples and tips serve as an accessible introduction to cleaning your house as Buddhist monks cleans their temples, for all through its explanations of the rituals of Buddhist cleaning.

Rituals such as cleaning your house/temple as the first task of the day. Not the whole house/temple every morning, that would be ridiculous; but rather making your first task every morning cleaning part of your house/temple, setting aside a specific period of time first thing every morning for cleaning your house/temple; and which for Matsumoto is important as "cleaning in the morning creates a breathing space for your mind so you can have a pleasant day."

Or can if while cleaning your focus is not only on your physical actions, but that you are also conscious of, receptive to, focussed on, the space around you and the relationships between space, task, objects, yourself and others; rather than complaining about the fact you're cleaning at such an early hour, and all the time wishing you were still in your bed.

Cleaning is a chore. A metaphor. A disposition.

And something that can be outsourced.

A great many of us paying someone else to clean our homes, which yes is another metaphor; and a disposition which becomes increasingly relevant when reflections on cleaning move from the private, individual, space to the public, collective, space.

In Berlin, and it's no exaggeration to say, one passes a litter bin every 100 metres. In Kyoto one passes a litter bin every 100 years: public litter bins largely only being supplied in popular tourist areas, for western tourists. Amongst the Japanese it is (widely) understood that, should you generate any rubbish while out and about, you take it home with you. It's your responsibility. In Berlin it's someone else's job.

A divergent understanding which was all too graphically illustrated to Birgit and Guillaume during a jet-lagged early morning walk following their return from Japan across Berlin's Tempelhofer Feld, the former Tempelhof Airport transformed into an near endless urban park and a popular location for meeting and socialising, or at least was, back in the day, so 2019. And which on that spring morning resembled a rubbish dump; the remains of the previous evening's meetings and socialisings strewn across the former outfield.

Logically, one could, if also deliberately provocatively, argue, in Berlin there are people employed to pick your rubbish up after you, so, why not leave it lying.......?

Which yes, is another metaphor. Or more accurately, is the same metaphor as paying someone to clean your house, just in a wider context, in context of a wider understanding of house.

And if understood as such, leads to a fusing, a coalescence, of understandings of private spaces and public spaces, of our private actions and our public actions, of the private me and the public me.

Understandings, in many regards, inherent in understandings of the function of cleaning in Buddhism, where cleaning the home/temple is undertaken not so much with the aim of keeping the home/temple clean, but as a component of the cultivation of the individual, as training for life.

As something you can’t outsource.

Understandings reflected in Japan, for example, in a long standing tradition that school children are actively involved in the cleaning of their schools, a task known as toban, and which is undertaken not so much with the aim of keeping the school clean but rather with the aims, and amongst others, of improving the pupils' interpersonal skills and their understanding of the value in cooperation.

And a task that follows many into their professional lives; in Japan it being not uncommon for office workers to be responsible for the cleaning of their office building, rather than outsourcing the task. In the course of their research Guillaume and Birgit spoke with Mitsuyasu Okamura from Kyoto based office supplies wholesaler Ueda Honsha, where, and as with the Buddhist temple, every day starts with cleaning, the staff spending 15 minutes every morning cleaning, and that not with the aim so much of keeping the office building clean, but rather through keeping the office building clean helping foster, for example, a collective understanding and a respect for your co-workers, Mitsuyasu Okamura adding that cleaning helps train "attention, consideration and autonomy" amongst the staff. Thus, one could argue, saving the expensive of not only external cleaners but of those generic, formulaic team building exercises no-one enjoys nor understands. And, arguably, bringing more sustainable benefits than outsourced team building exercises. Or outsourced cleaning.

In addition, once a month the Ueda Honsha employees clean the outside space around the office building, something Mitsuyasu Okamura refers to "as a contribution towards others and the environment."

A contribution, a task, that in Japan a number of voluntary and quasi-official organisations also undertake; for example, the improbably, and unintentionally sinisterly, named Kyoto City Beautification Promotion Agency organise weekly actions to collect that rubbish individuals didn't take home with them, similarly the non-profit organisation Green Bird, a movement established in Tokyo in 2003 and who now have chapters across Japan who organise local cleaning tours, one of which Birgit and Guillaume joined in Kyoto as a component of their research, and noting of the experience, "we would be curious to try it in Berlin...."

So they did.

Undertaking an explorative cleaning tour in the vicinity of their Neukölln flat with a number of volunteers, and collecting over the course of two hours four shopping trolleys worth of discarded items. And also spending 15 minutes every day for a week cleaning Fromet-und-Moses-Mendelssohn-Platz in front of feldfünf; the results of which form part of the Cleaning against the Dictatorship of Efficiency presentation and which amongst other considerations not only poses questions as to the apparent disparity between the provision of litter bins in Berlin and the utilisation of litter bins in Berlin, but also tends to underscore the urgency of reforming Berlin's take-away coffee habit. One of the most commonly occurring items discarded on Fromet-und-Moses-Mendelssohn-Platz being plastic coffee cup lids.

In Kyoto such is much less an issue, take-away food and drink in Japan tending to be taken away and consumed indoors. And not on the go, as is the apparent law in Berlin, it being apparently illegal to walk through Berlin without consuming a coffee and/or a sandwich and/or a Bockwurst and/or a beer. Just one of the many differences between Japan and Germany that feed into, enliven and deepen reflections on cleaning.

Not that reflections on cleaning only involves differences.

There are also similarities.

Similarities which pose, further, interesting questions of the differences.

Before studying design Birgit studied psychology, studies, and an interest, that inform and influence her design work, and thus, intrigued by the sheer number of cleaning related quasi-religions they discovered in Japan, undertook a literature review of psychological studies on cleaning and found evidence of links between physical cleanliness and, for want of a better phrase, moral cleanliness; that not only do we react in very similar fashions to physical and moral dirt, nor only does the cleanliness or otherwise of a space affect our assessment of situations as good or bad, nor nor only only are the areas of the brain associated with a reaction to physical dirt the same as those associated with a reaction to moral dirt, but, and as psychological studies have shown, when we feel morally unclean, when we feel we have done wrong, we physically wash, we physically clean ourselves.

When Shoukei Matsumoto talks about the links between cleaning, the heart, the soul and the mind he is both providing a synopsis of Buddhist teachings on cleaning, and describing an innate, verifiable, human characteristic: cleaning can make you feel better about yourself, creating a clean physical environment can create a clean mental environment, we feel better, we feel happier, in clean spaces.

But if that's the case, and we see no reason to question it, why the number of cigarette butts and coffee cup lids on Fromet-und-Moses-Mendelssohn-Platz? Why the scene that greeted Guillaume and Birgit that spring morning on Tempelhofer Feld? Why the variety and volume of rubbish collected on their exploratory cleaning tour of Neukölln......?

While there are invariably as many reasons for litter as items of litter, Birgit and Guillaume highlight a report by researchers at Berlin's Humboldt University which studied, and as the report is titled, Perceptions of cleanliness and causes of littering2, in Berlin, and found that personal reasons played an important role in littering, respondents primarily citing "laziness", "indifference", and a "lack of sense of responsibility towards the environment" as reasons for their litterous behaviour.

Some respondents also blamed an absence of litters bins. Which simply cannot be the case. Not only are litter bins omnipresent in Berlin, but litter bins are absent in Kyoto. As is litter. Or at least there is an awful lot less of both in Kyoto than in Berlin

What there is more of in Kyoto however is a Buddhist understanding of the value of cleaning, a Buddhist teaching of cleaning as more than just dusting, sweeping, washing, polishing et al; a teaching of cleaning as a metaphor which countenances against laziness, indifference, and a lack of sense of responsibility towards the private environment, and which pervades from the private environment to public environment, makes no difference between your responsibilities in your private home and in your public home, nor with the respect due to others in private and public spaces. And which in doing such tends to nurture a disposition that naturally leads to physical environments in (near) harmony with our innate need for, appreciation of, comfort arising from, cleanliness.

In Europe cleaning our private spaces is a chore we'd gladly give up, and public spaces are someone else's responsibility.

Which isn't a metaphor. But is an invitation to reflect on the disposition such an understanding nurtures, and the consequences that disposition has for ourselves, our communities, our societies and our planet.

An invitation extended in Cleaning against the Dictatorship of Efficiency.

Whereby it is important to note Guillaume and Birgit aren't claiming that Buddhist teachings on cleaning are a universal ideal, or that all in Berlin are irresponsible litter bugs, if we gave that impression, then only for rhetoric effect. Nor is Cleaning against the Dictatorship of Efficiency missionary advocacy for Buddhist teachings on cleaning, it's not; in conversation with Birgit and Guillaume one senses that they have very much assimilated many aspects of Buddhist teachings of cleaning into their own lives, but not in a fanatical manner, rather as a component of their wider understandings.

Much more Cleaning against the Dictatorship of Efficiency uses cleaning as a conduit via which to reflect on our relationships with not just our immediate environment and the wider environment, but also our relationships to one another, our contemporary consumer culture, our reliance on networked, digital, prosthetics, our understandings of collective and individual responsibility, and the health of our societies. Employs the very real differences between the understandings of the values of cleaning in Japan with understandings of the values of cleaning in Germany, and also the differences in practices, attitudes and contexts, as the basis for a differentiated perspective on our contemporary European societies, and by extrapolation poses relevant questions on how we want to, should?, must?, progress forward. Questions which, as we will never tire of noting, should never ever be outsourced....

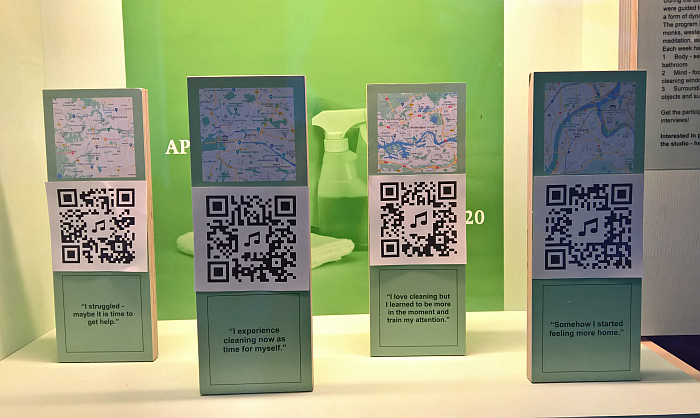

For all the very obvious limitations a window showcase brings with it, Cleaning against the Dictatorship of Efficiency through its intelligent use of photos, texts, videos and QR codes, nonetheless manages to provide a coherent, succinct, accessible, introduction to the Kyoto and the Berlin stages of Guillaume and Birgit's research and through doing so provides stimulus and incentive to delve deeper and question your own disposition. Or put another way, and to mangle Shoukei Matsumoto's metaphor: as a window on the project, it is a very clean window which provides for an unclouded view of a vista it recommends you explore.

And also introduces one of the more tangible results of the project: the jewellery collection Kirei.

A collection arsing from both the reflections on the (apparent) contradiction between the high value of the cleaning tools produced by Naito with the (perceived) low value of their intended action, and also reflections on those values of cleaning that are understood in Japan, but are often hidden in Europe, and transposing those reflections into a new context; a context where the value of the object is much more readily decipherable for European eyes, and thereby making reflections on both the hidden and visible values of cleaning more readily accessible.

A collection featuring three objects which reflect the three contexts in which for Birgit and Guillaume cleaning has an impact: our body, our mind/direct surroundings, and the wider environment/our interactions with others. Specifically: a necklace incorporating a sponge for cleaning your face and which reminds of the importance of looking after your environment with the same care and attention as looking after your body; a collection of gold rings which keep your fingers clean while you picking up litter, a truly brutal incongruity that is all the more unequivocal for the fact, and which for Birgit underscores the necessity to "step over our own mental boundaries" in context of cleaning as an action with a communal relevance; and a bracelet which is also a duster and which for Guillaume and Birgit is intended to highlight that cleaning is an active engagement with your environment, that through cleaning you naturally and automatically enter into a dialogue with your environment, ideally a questioning dialogue.

Which, yes, is a metaphor. And is also, in many regards, a central element of the project, an understanding that we all, continually, as unendingly and unfailingly as dust falls, engage in dialogues with our environment, but the tone, the nature, the direction of that dialogue isn't set, but is freely defined by us, and as Guillaume opines, "when you start interacting with your environment on a different basis this changes the way you look at your environment and how you think about your environment and your relationship with your environment".

As a project Cleaning against the Dictatorship of Efficiency is a gentle reminder to continually, and critically, reflect on our relationships with not only our environments but also our relationships with the people with whom we share those environments, and by extrapolation the degree to which we accept and enact our responsibilities to society, if we are conscious of our responsibilities.

Reflections cleaning offers an accessible path into, and which as Cleaning against the Dictatorship of Efficiency tends to underscore is a path we would be well advised to follow, or as Birgit very neatly and succinctly phrases it, "cleaning is not complicated, it is something everyone can do, and it isn't a very big step to realise that cleaning is not only good for you but good for others."

And thus the first step on a journey to an understanding that while cleaning is a chore, it also isn't.......

For all who can legally, safely and responsibly be underway in Berlin, and who feel comfortable doing such, Cleaning against the Dictatorship of Efficiency can be viewed in the windows of feldfünf, Fromet-und-Moses-Mendelssohn-Platz 7–8, 10969 Berlin until Thursday February 11th

In addition, and for all who currently can't make it to Berlin, the Cleaning against the Dictatorship of Efficiency research website offers bountiful insights, texts, photos and links, 24/7 and from the comfort of your own, and we're predicting soon much cleaner, home.

Further details on studio b severin and their work can be found at https://studiobseverin.com/

1Shoukei Matsumoto, A Monk' guide to a clean house and mind, Penguin Books, 2018

2Elke van der Meer et al, Wahrnehmung von Sauberkeit und Ursachen von Littering, Verband kommunaler Unternehmen e.V 2018 Available (possibly a bit cheekily) via https://www.staaken.info/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/VKU_Broschuere_Littering_Studie_Humboldt_Uni.pdf