#officetour Milestones – The Centraal Beheer Office Building by Herman Hertzberger

“The problem”, elucidated Herman Hertzberger in 1973, in context of his project for the Centraal Beheer insurance company in Apeldoorn, The Netherlands, “was to make an office building that would be a working place where everybody would feel at home: a house for 1000 people.”1

How Herman Hertzberger sought to solve that problem not only helping explain aspects of the development of architecture in the course of the 20th century, nor only aspects of the development of office design in the course of the 20th century, but also being informative in context of the problems associated with designing our contemporary, and future, office spaces……

The Centraal Beheer Office Building, Apeldoorn, by Herman Hertzberger, at its official opening on November 1st 1972 (photo Nationaal Archief via https://commons.wikimedia.org cc0)

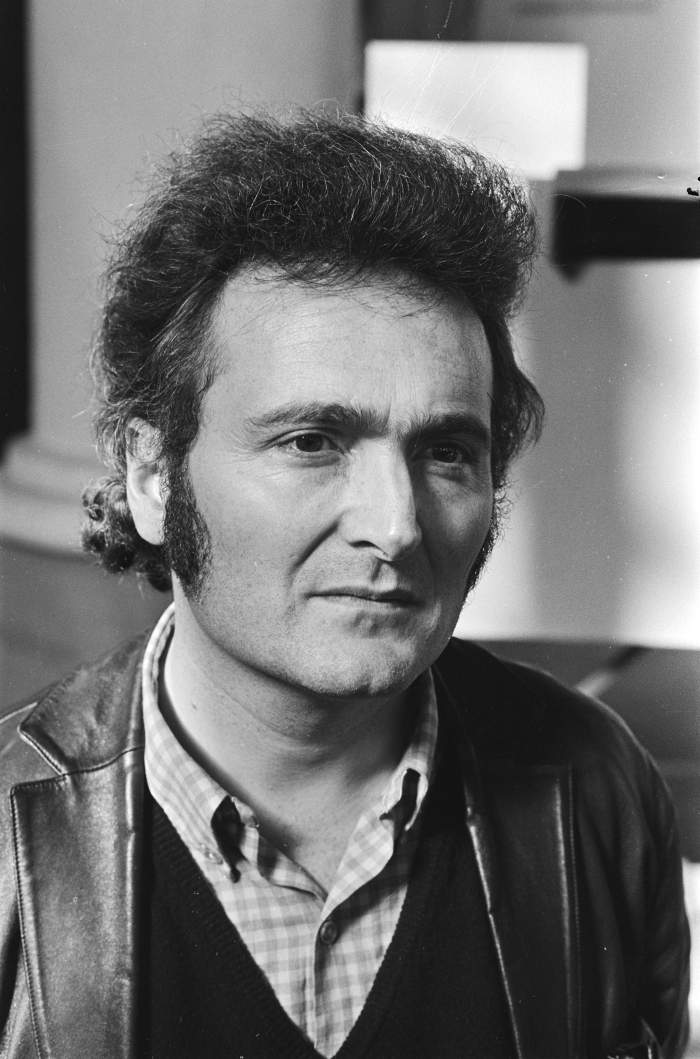

Born in Amsterdam on July 6th 1932 Herman Hertzberger studied architecture at Delft Technical University, graduating in 1958 whereupon he established his own studio, and the following year joined the editorial board of the Dutch architecture magazine Forum, an organ established in 1946 and to which in 1959 Jaap Bakema and Aldo van Eyck were appointed co-editors: two architects whose training in the 1940s had been very much in context of Functional Modernism, and two co-initiators of the so-called Team 10, a league of young architects who in 1960 broke away from the Functionalist Modernist orientated Congrès internationaux d’architecture moderne, CIAM, an institution founded in 1928, who counted a young Mart Stam, and a slightly older Gerrit T Rietveld, amongst its founding members, and which for the Team 10 protagonists had, if one will, ceased to become relevant; Team 10 demanding a move away from the rationalism and functionalism of the CIAM’s positions and the urgent development of new positions and approaches to architecture and urban planning, new positions and approaches that were more responsive to prevailing realities. And thus Jaap Bakema and Aldo van Eyck represent and embody an interesting, and important, transition in architectural positions and approaches in post-War Holland and in post-War Europe.

And important influences on the young Herman Hertzberger.

Not least in context of Structuralism, a theoretical, philosophical position which (largely) arose in early 20th century linguistics, and which in the immediate post-War decades increasingly began to inform other social and cultural disciplines, including architecture where, and summarising more than is perhaps prudent, it sought more humane responses than had often been the case historically, didn’t understand a building or a town plan as a closed definitive but rather sought to integrate social functions in a building, was interested in the participation of the user and accepted that change was inevitable over time, unknown, unpredictable change which should be anticipated by, integrated in, inherent of, any architectural or urban planning concept.

Structuralism which was at the heart of Forum in the 1960s; and Structuralism which is at the heart of Hertzberger’s Centraal Beheer office complex.

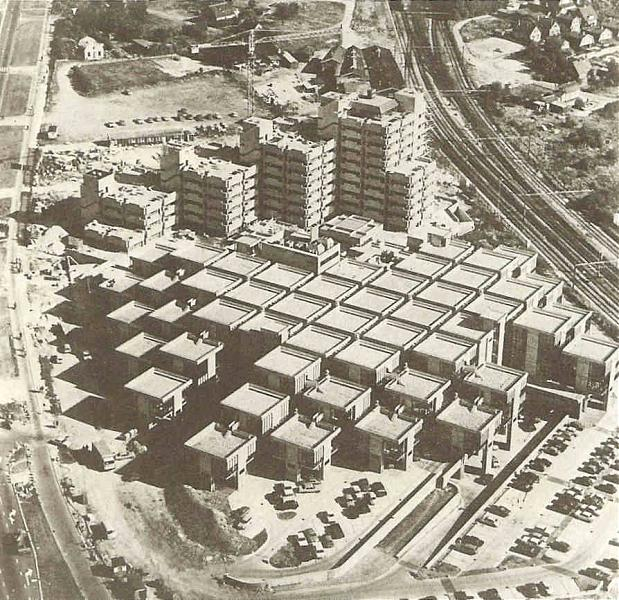

Established in Amsterdam in 1909, Centraal Beheer grew throughout the first half of the 20th century alongside the, then, fledgling Dutch social security system, before in the 1950s that growth was amplified through the sale of general insurance polices in the booming post-War consumer society; post-War growth which necessitated a new headquarters and saw Centraal Beheer move in 1972 from Amsterdam to Apeldoorn, and into a new office complex by Herman Hertzberger.

New in just about every sense of the term.

Although at the time of the Centraal Beheer commission in 1968 Hertzberger was, arguably, still better known as an architectural theoretician than a built architect, his first projects had been realised or were in construction, including a student housing project on Weesperstraat, Amsterdam, a Montessori school in Delft, or the so-called Diagoon experimental housing project, also in Delft. And early projects which all indicated what was to come in Apeldoorn.

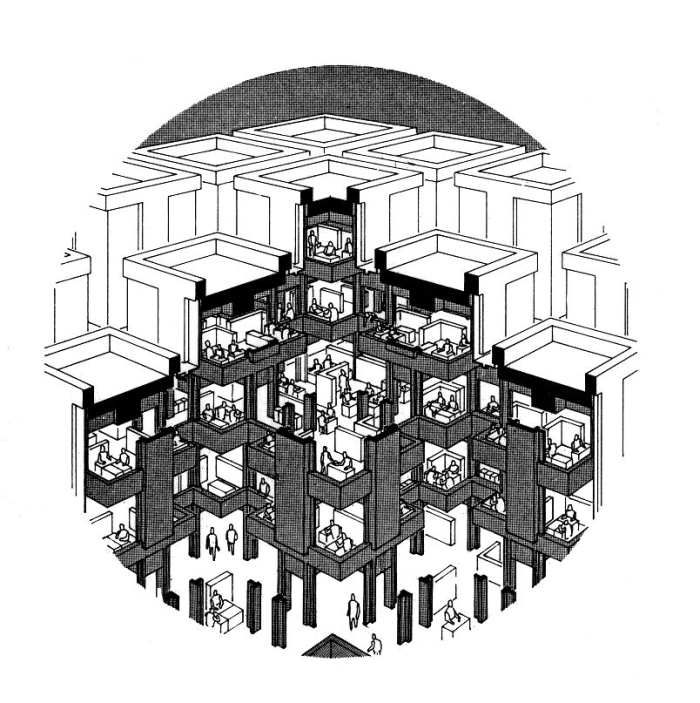

For Centraal Beheer Hertzberger, assisted by Jan Lucas and Henk Niemeijer, developed “a building as a sort of settlement, consisting of a larger number of equal spatial units, like so many islands strung together”2, two analogies in one sentence but which being such helps convey an appreciation of the Centraal Beheer office building as a sprawling collection of repeating forms linked together and stacked upon each other à la building blocks, specifically repeating 9m x 9m blocks.

Repeating 9m x 9m blocks which can be subdivided and “can accommodate the different programme components (or ‘functions’ if you prefer), because their dimensions as well as their form and spatial organization are geared to that purpose”3, repeating 9m x 9m blocks which are “independent of specific functions and interpretable”4 and “are therefore polyvalent”.5 A polyvalence that is very much at the core of Hertzberger’s expression of Structuralism; and a polyvalence we don’t want to get too bogged down with here, save to note that a polyvalent space can be considered as distinct from a precisely defined and structured functionalist space which through being precisely defined and structured excludes flexibility, and also distinct from generic, neutral spaces which have full flexibility but, for Hertzberger, are not only formally uninspiring but offer solutions that are never optimal, can only be but passive, generic, solutions.

Polyvalence in contrast being active and providing “a form that can be put to different uses without having to undergo changes itself, so that a minimal flexibility can still produce an optimal solution”6, which “entails introducing the greatest number of spatial conditions that can play a part in every situation whatever the function”7, and which in being such enables a space that can move away from the “collective interpretations of individual living patterns” demanded by Functionalism and opens the opportunity for “individual interpretations of communal living patterns”.8

Or, and to remain in context, to move away from collective interpretations of individual working patterns and allow for individual interpretations of communal working patterns.

And thereby allows an office to become a social space as much as a work space.

The Centraal Beheer Office Building, Apeldoorn, by Herman Hertzberger. As a model (Photo Het Nieuwe Instituut via https://commons.wikimedia.org)

Although offices have, in many regards, always been social institutions, there has always been social contact and interaction of some form between those employed in offices, throughout the (hi)story of the office it was never a component that was particularly at the fore, certainly not one that was overly or overtly encouraged, a reality perhaps best exemplified by the dehumanising scientifically optimised offices of the first decades of the 20th century with their rows upon rows of desks, the employees little more than cogs in a machine, endlessly shifting bits of paper from one file to another.

The question of the individual within the community didn’t exist in such a space, was impossible to frame, there was no concept of the individual in an early 20th century office; similarly the question of the role or function of the office wasn’t one that could be posed in the first half of the 20th century, offices were for work. What was there to discuss? Then came the 1950s, then the 1960s, new understandings of society began to develop and evolve, contemporary understandings which questioned relationships between the individual and the collective, which questioned power and control structures, questioned established hierarchies, questioned social conventions, questioned the place of the individual in society, and which inevitably began to allow questions of the office, of office work, of the office worker to be framed and posed.

Herman Hertzberger’s Centraal Beheer office building can be considered as one of the first attempts to approach questions of what an office is, what an office can be, what an office should be, against the background of, in context of, evolving contemporary understandings of European society. And also as one of the first attempts to approach the question of the individual employee within the office community.

Or as Hertzberger opines, any new building “is the prepared ground on which can take place a reappraisal of relationships, involvements and responsibilities which perhaps fortuitous in their origin have become self-disseminating, a coagulation of rusted parts”, and that an architect can “through his proposal animate people into thinking up other new possibilities”.9

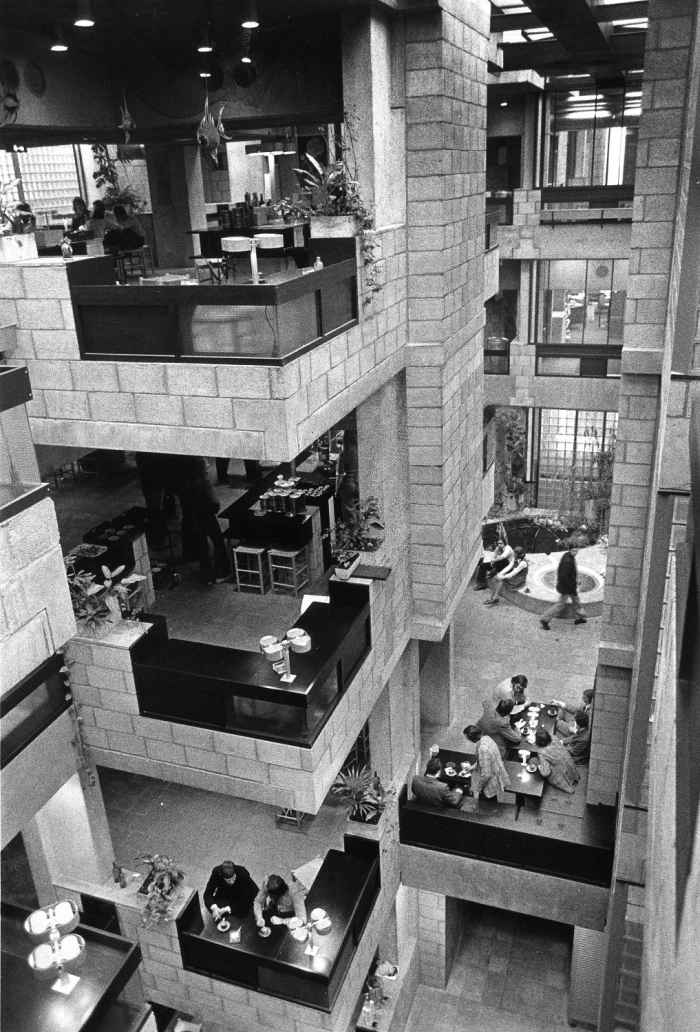

To this end Herman Hertzberger developed a space for Centraal Beheer, for Centraal Beheer’s employees, which fundamentally redefined the open-plan office, that dominant form of large, commercial office in the 1960s; specifically Hertzberger developed “a building as a sort of settlement” whose urban understandings of itself went beyond the physical structure with it’s network of wide boulevards and narrow arcades, it’s telephone boxes, it’s impluvium to catch rain water, it’s structures of varying heights which allow the space to be fully claimed vertically as well as horizontally, and the ever new vistas across the space depending on the route taken through it or the height at which you found yourself, and which also included, encompassed, a more conceptual understanding of a city, reflected the reality of a city as a mix of public spaces, private spaces and in-between spaces. A mix of spaces not to be confused with the strict zoning of the functionalist city, but rather as a free mix of spaces which, as with the spaces in a non-planned city, the residents define, control are responsible for, individually and collectively, and which every resident can read and implicitly understands. A mix of public spaces, private spaces and in-between spaces office buildings previously hadn’t had. Couldn’t have imagined having.

And a mix of spaces augmented by incentives. No, not the free fruit, pool tables or early morning yoga sessions that are considered incentives in contemporary offices, but unfinished, undefined, bare components and spaces, aspects which are found in any city, or at least any city allowed to develop itself rather than being fully defined by the authorities, which yes does bring us back to Lucius Burkhardt, and which for Herman Hertzberger “represent an invitation for completion and ‘colouring’ by the people who live there”10, “evoke associations in the user, which in turn lead to specific adjustments to suit specific situations”11 and thereby influence and inform the individual’s relationship with a space. Ideally for the benefit of all. And incentives which in the Centraal Beheer office complex were perhaps best articulated by the fact staff were encouraged, empowered, to bring in their own plants, pictures, objets d’art, whatevers, even furniture, to decorate their corner of the office as they saw fit and thereby claim it as their personal, private, individual, space. Something utterly unthinkable just a few years earlier, and something which was of central importance to Hertzberger as it meant not only that that “everyone’s choice, and thereby his standpoint, is brought into the building”12 but also enabled the employees to take possession of the building, individually and collectively.

An incentivising of an office space Hertzberger argues is only possible in situations where “the liberty to take personal initiatives” is “embedded in the organizational structure of the institution concerned”, where the question of “how much responsibility the top is prepared to delegate”13 is answered in a number substantially greater than zero.

A liberty and delegation which needn’t express itself in an over-abundance of macramé plant holders and pictures of cats, but, Hertzberger tends to imply, will invariably be reflected in how an office functions and how happy and satisfied employees feel; and which is an important reminder that if an institution’s management isn’t receptive to open, empowering, structures then regardless of what architects and designers propose, a contemporary office can be every bit as dehumanising as those of the early 20th century.

The city analogy of the Centraal Beheer office building is taken to even further extremes by the manner in which the building connected with, and was intended to further connect with, Apeldoorn.

Whereas many today seek to bring the outside in and to link an office to the surrounding city through large glass windows, a purely figurative connection, Herman Hertzberger made, or at least intended to make, the Centraal Beheer office building an actual component of the city, part of the furniture of the city: a connection to the new Apeldoorn railway station to the south and an underpass to downtown Apeldoorn to the north meaning the pedestrian route from downtown Apeldoorn to the city’s railway station would have passed along the central boulevard of, straight through, the Centraal Beheer office building. Would have. But the new railway station was never realised, nor the underpass; however, the building itself was very much open, as in freely accessible to all and everyone, a free accessibility underscored by their being no main entrance rather numerous city gates, open to all and providing for a fluid, individual, connection with Apeldoorn. In addition in was very much intended that your family could and should drop by to visit and/or have lunch in the company cafeteria, thereby blurring the borders between home and office, between private and public, even more than we manage today. But arguably in a more socially positive manner.

And a city analogy further expressed by that ubiquitous and omnipotent competent of any contemporary urban space: the coffee bar.

Every floor in the Centraal Beheer office building had its own coffee bar, every coffee bar staffed by its own dedicated baristas, empowered and encouraged to personalise their space, and thus every coffee bar with its own character. Coffee bars at which employees could take a break or gather for meetings, and also where you could meet friends and family, and thus coffee bars which were very much of part of the open, public, nature of the office building.

Until that is the coffee bars were replaced by coffee machines.

We weren’t there, we don’t know, but we suspect that the change was made for financial reasons, we can see no other explanation; but was, for us, a very, very retrograde step.

And for all symbolic of the numerous changes the Centraal Beheer office building underwent that affected its understanding of who it is: some necessitated by changes to building regulations; some caused by societal changes, not only did over time an office building open to all cease to be understood as a good idea, but also, the 1980s arrived, and then the 1990s arrived, or as Hertzberger opined in 1994, “the idealism of social democracy has collapsed, people feel less responsible for the whole”.14 And yet other changes driven by the reality of corporate society: in 2013 Centraal Beheer, since 2001 part of the Achmea group, moved to a new office building on the shiny new Achmea Campus on the southern edge of Apeldoorn.

Since when Herman Hertzberger’s Centraal Beheer office building has stood empty.

A state of affairs which tends to lead to the question, how successful was the Centraal Beheer office building during its 40 years of service? Did it meet the challenge to provide “a house for 1000 people”?

(Video ca. 2 minutes, in Dutch but with some nice views of the inside)

We no know.

Not only did we never work in it, but we can’t locate any research on the Centraal Beheer office building in use, can’t locate anything which indicates any form of structured analysis was undertaken once everything was up and running. As ever we may just not be finding it, and we will keep looking15; but based on that which we can find the Centraal Beheer office building exists very much as one of those architectural experiments where at the opening the architect explains in great detail their concept and idea, critics of various hues have their say, some consider it genius, others awful, and then all move on to the next new awful/genius thing. No-one thinking to go back after 5 or 10 or 15 or 25 years and ask those who use it how they are getting on with it, how they are liking it, what’s good, what’s bad.

But which is surely what is important, surely that which must be done. And which in not being done tends to imply how architecture works.

What one can say with more certainty is that over time it was appreciated that what Hertzberger’s polyvalent city lacked was the possibility of a large space for staging communal events, in keeping with the urban analogy, the city of Centraal Beheer lacked a forum, and so in the early 1990s Hertzberger added an extension with just such a space.

And, as Ernst Hubeli notes, in Hertzberger’s subsequent projects, perhaps most relevantly the Ministry of Social Welfare and Employment in The Hague, a project developed throughout the 1980s, some of the more extreme elements of Centraal Beheer were scaled back, in the Hague Ministry there are even individual offices. Hubeli talks of such later works as correcting the “mistakes made in Centraal Beheer”16, whereby we’d take issue with the word “mistakes”. Centraal Beheer was deliberately extreme, deliberately carried existing understandings into new terrain with no clear map for the way forward once they got there, unsure if there was even a way forward or if they would sink in a bog; and when one undertakes such a mission, corrections to the original plan are inevitable, must be anticipated and should never be considered “mistakes”, rather embraced as useful experiences. And as Herman Hertzberger noted in 1994, “I have learned a lot from Centraal Beheer”.17

Or put another way, in 1973 Hertzberger proclaimed, “this building is a hypothesis. Whether it can withstand the consequences of what it brings into being depends on the way in which it conforms, with the passing of time, to the behaviour of its occupants.”18

Questions the lack of follow-up research make very difficult to answer with any degree of certainty; however, as a hypothesis distinct from the physical building, Centraal Beheer has, we’d argue, withstood the passing of time very well, remains very relevant in considerations on contemporary and future office design and office building design. Is something we can all learn from.

Not least because with the Centraal Beheer office building Herman Hertzberger framed for the first time questions on the office that remain to this day unresolved.

Or perhaps better put, questions we understand today as having no single correct answer, we understand today as having no universal solution, but which much more require the development of frameworks in which to allow them to be continually approached anew. Flexibility in any office space being more than a physical demand.

Questions such as that of the individual in the community.

Any contemporary office is, by necessity, an interplay between the individual and collective, one could argue that the success or failure of any contemporary office is an expression of the success or failure of the integration of the individual and collective. Centraal Beheer offers scope for critical reflection on the myriad subjects entailed in such an interplay. On subjects such as, and amongst others, the division of space and the question of who is responsible for the definition of any given space as being individual or collective or mixed, as being private or public or intermediate? How do such definitions change over time? What happens when definitions are challenged?

On subjects such as, and amongst others, participation, which in context of any office building is ongoing and universal, every user participating with an office building every day, but how could, should, one manage participation? Are there borders to participation? If so, who sets them?

On subjects such as, and amongst others, incentives, which can be yoga, can be macramé plant holders, but could also be more conceptual, or non-existent: should one leave unfinished space in an office building? If so how and where? Physical space or conceptual space? And how can one prevent an incentive from becoming a coercion, something one feels obliged against one’s nature and/or better judgement to do, and thereby risk upsetting the individual/community equilibrium?

The glass ceiling over a “street in the Centraal Beheer Office Building, Apeldoorn, by Herman Hertzberger (photo Apdency via https://commons.wikimedia.org cc0)

Questions such as that of the role and function of the office.

If one reads, for example Im Bureau, Robert Walser’s recollections of the office in ca 1900, one is clear that at that time the office was understood as the primary arena in which an employees daily life was experienced, was where you spent most of your waking day, a state of affairs no-one claimed to be happy about, but that was just one of these things, something you accepted and got on with.

By the 1960s it was appreciated that the fact many office workers spent the greater part of their waking day in their office was an issue to be addressed, wasn’t something to be blithely accepted, and which forced questions of the office to be reframed, reformulated. The fact that in 1973 Herman Hertzberger could refer to an office as being a “home-from-home”19 was relatively new, until only very recently an office had been an office.

And looking forward questions of the office as a loci of daily life will require further reframing, reformulating, if, as appears probable, ever more of us not only work ever more often from home, but work shorter weeks. A four day week, for example, with two of them in home office and two in the office office, and all your work hovering in a cloud, radically alters your relationship with the office office; doesn’t diminish its importance, it remains the space that connects you to the company, your colleagues and confirms the joint objectives necessary for a successful company/institution. But through new work practices and through new technology ceases to be a space you need for work work.

And that means……?

Herman Hertzberger also designed some of the furniture for the Centraal Beheer office building, including charmingly simple desks…..

Questions such as that of the form of an office space.

Not just the physical form but also the theoretical form, the underlying conceptual structure.

The Centraal Beheer office building is not only structurally aligned with an idealised city, a structural alignment that radically alters your view of what an office is and can be; but can also be considered very much in context of Hertzberger’s position of architecture as analogous to weaving, the fabric of a building or urban space being analogous with a woven fabric, and of the importance of the interplay of warp and weft: the former being for Hertzberger the structure, physical and conceptual, provided by the architect or designer and which “establishes the basic ordering of the fabric”, the later the “individual interpretations” that are woven in, the relationships that develop, and determine “the appearance of the end-product”.20

A position which enables differentiated considerations on, for example, the aforementioned link between the positions of an institution’s management and the daily reality in the office space, or on the relationships between an office building and an office community, or on the inter-relationships, inter-dependencies, between an office space and office workers, that both space and worker affect, influence and inform the other. That it is an unpredictable, free, two way process, which occurs within a set structure.

And questions posed by reflections on the Centraal Beheer office building which also allows one to shift one’s focus from considerations on the office building as a home, to considerations on the office community as a family, to shift your focus from the problem of providing a house within which 1000 people should feel at home, to the problem of providing a family within which 1000 individuals should feel at home. Something we can do today because of contemporary understandings of the family, of the family unit, understandings that have developed a lot since the 1970s and seen the term family become much less clearly definable than it once was, if remaining every bit as important.

And in enabling such the Centraal Beheer office building helps continue to shift the focus in office building design from the physical to the emotional, from the creation of working environments to the creation of social environments.

And, yes, in such a context a coffee bar on every floor probably should be obligatory in all office buildings.

Not that the Centraal Beheer office building should be held up in itself as a paragon; however, reflections on Herman Hertzberger’s Centraal Beheer office building can remind us that the problems of office design are rarely new, just continually framed and approached in ever new social, economic, technical, political, et al contexts.

(Video ca. 12 minutes, spoken Dutch, English subtitles, 1970s attitudes and smoking at desks. And don’t forget, although much of what you’re seeing in terms of office design may appear familiar, it is very new…..)

In the interests of completion, the writing of his text was accompanied by the music of Focus, specifically the albums In and Out of Focus, Moving Waves, Focus 3, Hamburger Concerto and Live at The Rainbow, a bit early 1970s Dutch Prog striking us as providing the optimal acoustic background…..

1. Herman Hertzberger, An office building for 1000 people, in Holland, Domus No. 522, May 1973

2. Herman Hertzberger, Lessons for Students in Architecture, 010 Publishers, Rotterdam, 2005

4. Herman Hertzberger, The Future of the Building “Centraal Beheer”, July 2016, available via https://www.hertzberger.nl/index.php/en/nieuws2/51-recent-publications (accessed 26.11.2021)

5. Herman Hertzberger, Lessons for Students in Architecture, 010 Publishers, Rotterdam, 2005

7. Herman Hertzberger, Polyvalence. The competence of form and space with regard to different interpretation, Architectural Design, Vol. 84 Nr. 5, September 2014,

8. Herman Hertzberger, Lessons for Students in Architecture, 010 Publishers, Rotterdam, 2005

9. Herman Hertzberger, An office building for 1000 people, in Holland, Domus No. 522, May 1973

10. Herman Hertzberger, Lessons for Students in Architecture, 010 Publishers, Rotterdam, 2005

12. Herman Hertzberger, An office building for 1000 people, in Holland, Domus No. 522, May 1973

13. Herman Hertzberger, Lessons for Students in Architecture, 010 Publishers, Rotterdam, 2005

14. Elke Trappschuh, Interview with Herman Hertzberger, in Alexander von Vegesack [Ed.], Citizen Office. Ideen und Notizen zu einer neuen Bürowelt, Steidl Verlag, Göttingen, 1994

15. Aside from general issues one particularly interesting question is that of the effect of automation and digitisation on the use of the Centraal Beheer office building. As Tjerk Huppes notes [Tjerk Huppes, The Western Edge. Work and Management in the Information Age, Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, 1987], in the two decades between 1965 and 1985 automation at Centraal Beheer led to a radical re-organisation of the work division, work flows and departmental structures. An organisational restructuring which thus occurred predominately in Apeldoorn, but how well, or badly, did Hertzberger’s polyvalence support the changes through increasing automation? A question give further zest by Arthur S. Weinberg’s comment in 1976 that at Centraal Beheer, “at this time, the working environment is unique, but the job tasks and organizational structure are still traditional” [Arthur S. Weinberg, Industrial democracy in the Netherlands, Monthly Labor Review, Vol. 99, No. 7, July 1976 ]. A statement which tends to indicate that the nature of the new working methods and structures enforced by automation weren’t anticipated, couldn’t have been anticipated, during the planning of the Centraal Beheer office building, which is, more ore less what polyvalence tells you will be the case, but did polyvalence assist or hinder the integration of automation? Just one of the many things it would be useful to better understand, which would be helpful in allowing more probable understandings of Centraal Beheer.

16. Ernst Hubeli, Nach Centraal Beheer. Neue Bauten und Projekte, Werk, Bauen + Wohnen, Volume 76, Nr. 10, 1989

17. Elke Trappschuh, Interview with Herman Hertzberger, in Alexander von Vegesack [Ed.], Citizen Office. Ideen und Notizen zu einer neuen Bürowelt, Steidl Verlag, Göttingen, 1994

18. Herman Hertzberger, An office building for 1000 people, in Holland, Domus No. 522, May 1973

20. Herman Hertzberger, Lessons for Students in Architecture, 010 Publishers, Rotterdam, 2005

Tagged with: #officetour, Apeldoorn, Centraal Beheer, Herman Hertzberger, holland, milestones, polyvalence