In 1947 the American designer Edward J Wormley reflected in the New York Times on what contemporary furniture could, should, be, and amongst his thoughts on beds, chairs, storage units et al, opined that "an ideal table would be a flat plane suspended in space", and that not least because "it's the legs that are the big nuisance".

"Can we find this kind of furniture in today's market?", he asked his readers, albeit, rhetorically, "You know we can't."1

Which tends to imply Wormley didn't visit the Home Show exhibition in New York in April 1930, for had he, he would have seen Friedrich Kiesler's Flying Desk.......

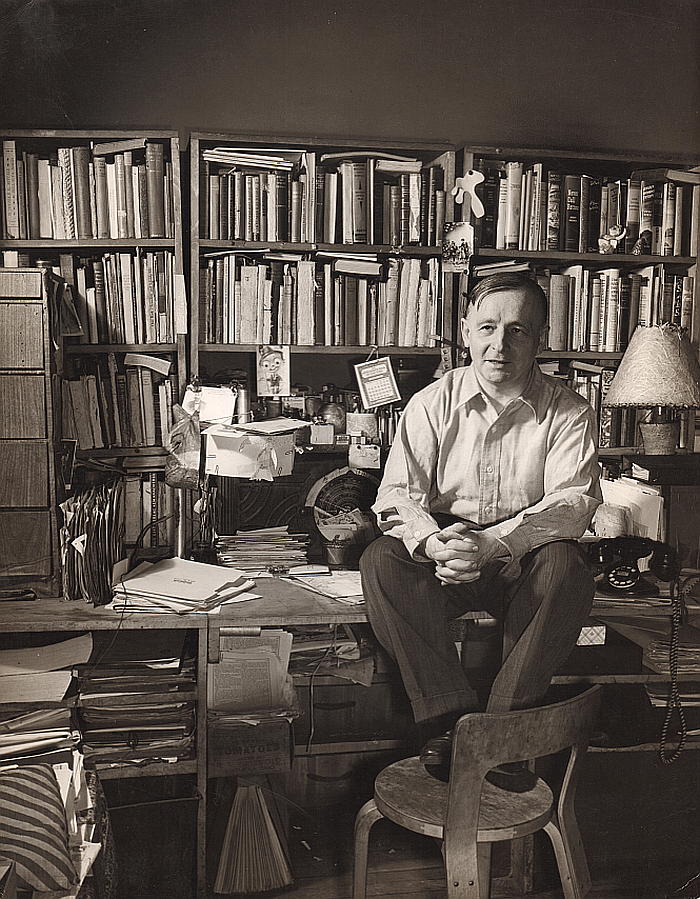

Born on September 22nd 1890 in, then Czernowitz, Austro-Hungary, now Chernivtsi, Ukraine, Friedrich Jacob Kiesler moved to Vienna in 1908 where, following a year studying architecture at the Technischen Hochschule, he enrolled in the Akademie der bildenden Künste, spending the next three years studying under, amongst others, the Wiener Secessionists Ferdinand Schmutzer and Rudolf Bacher, and, possibly, also the architect and urban planner Otto Wagner.2 The outbreak of the Great War saw Kiesler called-up for military service, the exact details of which, as with so much of the early Kiesler biography, appear lost in the mists of time, but by all accounts included a period with the so-called Kriegspressequartier, a propaganda unit within the Austro-Hungarian army whose members read like a who's who of the coming generation of Central European creatives including, and amongst many others, Ferenc Molnár, Egon Erwin Kisch, Oskar Kokoschka or Felix Salten, the real father of Bambi, before in 1923 Kiesler first made a name for himself in that discipline with which he is so closely associated: theatrical stage design. Specifically developing the scenography for the German language premiere of Karel Čapek's R.U.R. Rossumovi Univerzální Roboti, germanified as W.U.R. Werstands Universal Robots3, a work which centres around androids built and sold as cheap labour for factories, before they become ever more autonomous, rebel and cause the extinction of the human species, and almost their own extinction, before love saves the day. Thus a work very much in context of the new world visions, and new world fears, of the inter-War years and its various and varied utopias. And very much in context of our own contemporary technological developments and their associated utopias. (And dystopias)

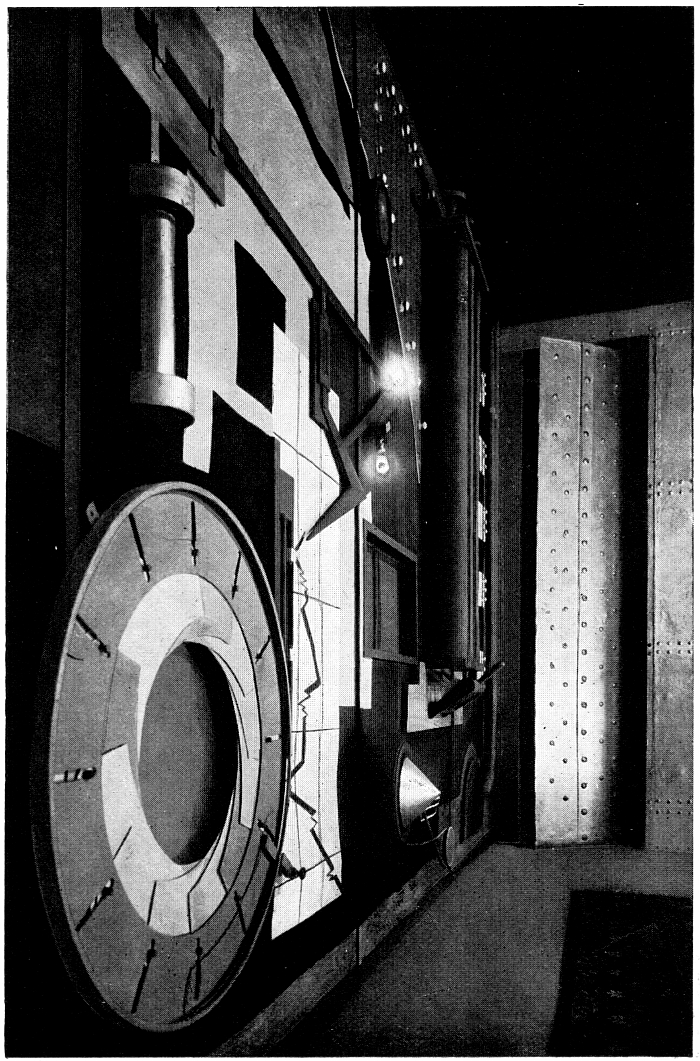

A stage design for which Kiesler, in keeping with the futuristic technological vision of Čapek's work, integrated what he refers to as a "first attempt at an electro-mechanical scenery", a composition in which "rigidity is brought to life. The backdrop is active, participates". And a scenography which mixed film with the live performance, for all through the electro-mechanical, "iris diaphragm, 1.10 m in diameter ... The diaphragm opens slowly: the film projector rattles, a film is cast on the circular surface, cranked off at lightning speed, the diaphragm closes".4 A stage setting of movement, light, film, noise, colour, automation, confusion which according to a popular anecdote, which may or not be true, saw, after one of the earliest performances, Kiesler triumphantly carried off to a Berlin club by an exuberant crowd of Theo van Doesburg, Hans Richter, László Moholoy-Nagy, Kurt Schwitters, El Lissitzky and Werner Graef where they subsequently spent a long evening, together with Mies van der Rohe who they, allegedly, met at said club.5 And whether true or not, we certainly weren't there and so can neither confirm nor deny its validity, but regardless of that validity, the anecdote does very neatly underscore the breakthrough moment of Kiesler's W.U.R stage design, the arrival of Kiesler in the 1920s cultural avant-garde, something underscored by the depiction of the stage design in the May/June 1923 edition of De Stijl's NB magazine.6 And also marks the start of a great many, long-term, friendships between Kiesler and members of that avant-garde; friendships which were to be important in the development of not just Friedrich Kiesler, but of those friends. And by extrapolation the development of art, architecture and design.

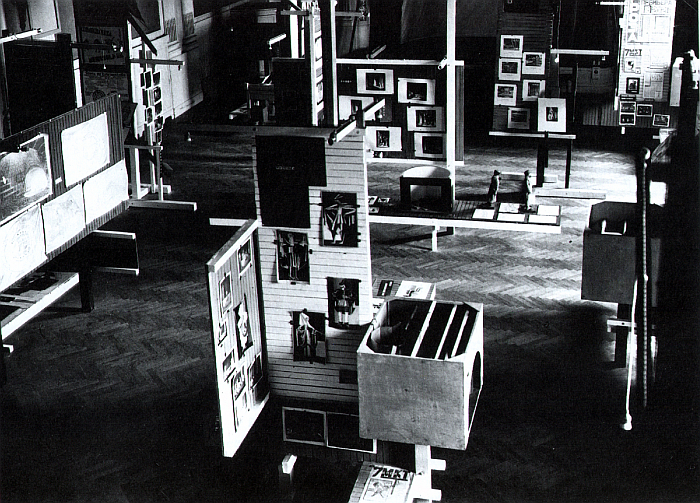

In 1924 Friedrich Kiesler organised the Internationalen Ausstellung neuer Theatertechnik [International Exhibition of Modern Theatre Technic] in Vienna, an event that presented works from a cross-section of the European avant-garde including, and amongst many, many others Ferdinand Leger, Oscar Schlemmer, Kurt Schmidt, Max Poelzig, Enrico Prampolini, Alexander Wesnin or Alexandra Exter and which in bringing together such protagonists helps underscore the popularly under-rated role theatre played in the development of art, architecture and design of the inter-War years, of the differing role of theatre in society and culture in the age before television.

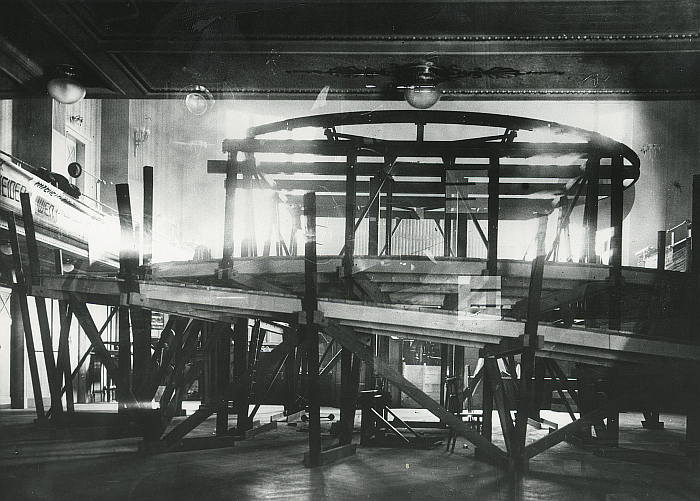

Among Kiesler's own contributions to the 1924 exhibition was the so-called Raumbühne, Spatial Stage, a, as Barbara Lesák notes, stage concept that stood as a "strict antithesis to the figurative, visual, stage of the proscenium theatre"7, a strict antithesis from a contemporary reality in which for Kiesler, "the proscenium stage is a box attached to the auditorium. The shape of this box is the result of technical considerations, not the particular play", and that "our theatres are copies of dead architecture. Copies of outdated systems. Copies of copies. Baroque theatre": or were, for as pronounces Kiesler, "for us the illusion theatre and illustration theatre is over"8. The Internationalen Ausstellung neuer Theatertechnik can be understood as dozens of manifestos as to how the way forward from the contemporary/baroque illusion theatre and illustration theatre could be constructed.

For Kiesler himself it was clear that "today's theatre demands a vitality as is found in life, and this vitality with the power and pace of the times", "the new will explodes the figurative, visual, stage in order to dissolve it into space, as required by theatrical art", and thereby "it creates the Raumbühne, which is not only a priori space, but also appears as space".9 A Raumbühne as an essentially empty domain which is bequeathed a three dimensionality in contrast to the two dimensionality of the figurative, visual, stage and given life and meaning, a relevance to the particular play, by the form of the space, the viewers perspective and the movement of the actors within that space; and a Raumbühne which in the form of the so-called Railway Theatre Kiesler presented in Vienna, a rising spiral with a circular platform at the top, "...floats in space. It only uses the ground as a support for its open construction".10

In addition Kiesler developed for the Vienna exhibtion his so-called Leger und Träger System, Beam and Girder System, an exhibition design system of thin horizontal and vertical supports to which were attached platforms for objects and panels for posters/texts, a standardised, reconfigurable, reusable, reduced, cost-efficient, still extremely relevant, exhibition design system developed with the aim of moving away from the classical exhibtion display practice of objects on and along the outer walls of a room and thereby allowing "the opportunity to dissolve the rigidity of space" and to create an exhibition which "forces the visitor not to skip, miss, anything; to engage with each individual object"11; and a system which, certainly from the photos we've seen, very much reminds of a Piet Mondrian painting opened up, exploded, into an immersive 3D experience.

And a Leger und Träger System Kiesler also employed in his design for the Austrian Theatre Section at the 1925 Exposition internationale des Arts décoratifs et industriels modernes in Paris. And where he, at least conceptually, raised it from an exhibition design system to an urban planning concept: Die Raumstadt, the Spatial City. So called because "it floats freely in space in a decentralized federation dictated by the ground-formation", and a component of Kiesler's demand for an "elasticity of building adequate to the elasticity of living"12, a world without the walls and restrictions which architecture forces on society and within which society is bound. And a world of, as Kiesler phrases it, Tensionism, "an elastic building system of tubes, platforms and cables developed from bridge building".13 Layered cities which grow in all dimensions.

An architectural concept that is and was Friedrich Kiesler's first notable contribution to contemporary architecture discourse, but far from his last, throughout his long career Kiesler developed a great many architectural and urban planning concepts. If realising only very few.

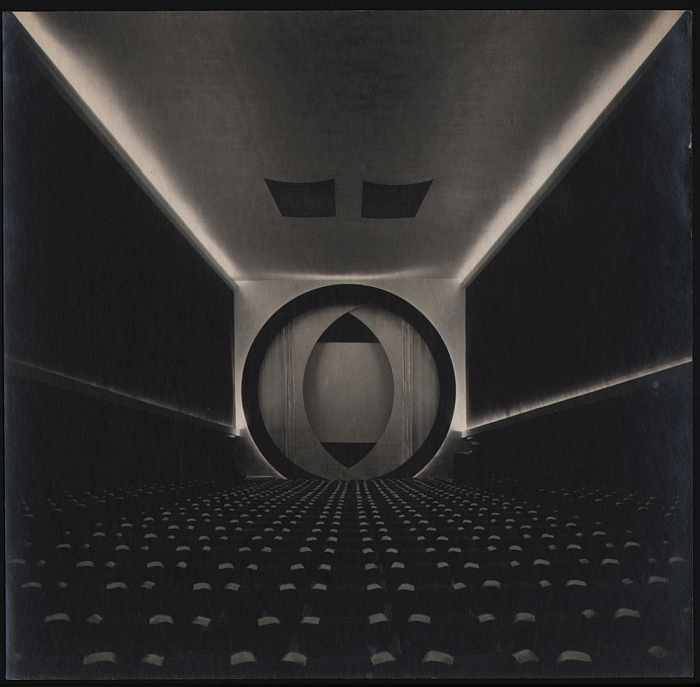

The first he did realise being not uninterestingly the Film Guild Cinema in New York.

Opened to the public in February 1929 the Film Guild Cinema sees Kiesler very much seeking to shift the design of movie theatres away from the theatre theatres they at that point largely mimicked, much as he sought to shift the design of theatre theatres away from the outdated models they mimicked, and also sees Kiesler seek to both underscore the international nature of cinema by doing away with the national/regional influenced ornamentation and decoration of movie theatres, and also respond to the, for him until then under appreciated, fact that "the film is a play on surface, the theatre a play in space"14 and thus required differing environments. Much as 1920s theatre theatre demanded a different environment to baroque theatre.

To this end Kiesler developed an ornament and decoration free auditorium whose interior lines were designed to "focalize to the screen compelling unbroken attention of the spectator", which featured stadium seating, i.e. seats on a sloping platform rather than on the flat floor of a theatre, and walls painted black to ensure total darkness when a screening was underway, thereby allowing the viewer to concentrate fully on the film and "be able to lose himself in an imaginary, endless space even though the screen implied the opposite".15 An imaginary, endless space augmented by Kiesler's design which decreed that not just the frontal screen was a projection surface, but that all walls and the ceiling could "be used when the action surges beyond the confines of the main screen"16, thereby enabling an immersive experience.

While, where normally curtains would hang in front of a screen, Kiesler installed his so-called Screen-o-scope, which opened like an eye to reveal the screen. And which reminds very much of the electro-mechanical iris diaphragm of W.U.R. Werstands Universal Robots. And a movie theatre which, as with the Raumbühne, stands in strict antithesis to the proscenium film theatre.

And a 1929 project with which we'll stop our tour through the Kiesler biography, for while the decades between 1929 and Friedrich Jacob Kiesler's death in December 1965, by then an American citizen and formally Frederick John Kiesler, are decades full of fascinating and informative and engaging architecture, urban planning, art, furniture design, shop window design, stage design, et al projects, works, and a great many texts, we can thoroughly recommend you acquaint yourselves with you should you not already be, he is an endlessly engaging creative, our focus here is to be found in Friedrich Kiesler's next project, the 1930 Home Show in New York.

Staged in New York's Grand Central Palace the Home Show, as best we can ascertain, appears to have been a mix of retail exhibtion and forum for contemporary positions and projects; the 1930 edition featuring, for example, a display of large-scale urban planning, and traffic planning, projects and plans in and around New York, alongside real estate companies pitching their latest projects, banks pitching financing, telephone and electric companies pitching for customers, and whose presence underscores the context of the age in which the show was held, and also presentations of contemporary furnishings and interior design solutions, the latter including a number of rooms designed by the American Union of Decorative Artists and Craftsmen, AUDAC.17

Established in New York in 1928 AUDAC was an association of designers, architects and artists "working for the elevation of contemporary design", primarily in context of interior design, and an organisation "convinced that contemporary life demands an appropriate setting and that it is the work of the artists of all ages to mould the external world to suit the life of his time"18, to which we'd add "discuss", but we digress.....; and an organisation which as Christopher Long argues was also concerned with achieving a tightening of copyright legislation in terms of furniture design, and which he opines "...became one of the principle activities of the organization. Copyright laws at that time offered scant protection for designers of furniture or decorative accessories"19, and leading to a situation which, according to the AUDAC, was "so rampant, so flagrant, so bold ... that continental artists now vehemently refuse to participate in American exhibitions, for fear that their ideas be stolen as they have been in the past".20 In how far that is actually true we know no, but one can be certain that the AUDAC played an important role in ensuring the passing in July 1930 by the US Senate of the so-called Vestal Bill which provided copyright protection for "pattern, shape, or form ... which produces an artistic or ornamental effect or decoration, but shall not include patterns or shapes or forms which have merely a functional or mechanical purpose".21 Form clearly not following function in 1930s America, despite Louis H. Sullivan having asserted in 1896 that it very much did. Was in fact "the law".

In addition the AUDAC was through its regular social events a not unimportant platform for exchange amongst its members22; a membership which included a mix of American creatives including, for example, and amongst others, Harvey Wiley Corbett, Normam-Bel Geddes, Marguerita Mergentime or Frank Lloyd Wright, and also European émigrés such as, and again amongst others, Lucian Bernhard, Albert Kahn, Ilonka Karasz, Eliel Saarinen or Paul T. Frankl23, the latter playing an instrumental role in the establishment and operation of the AUDAC; and thereby the AUDAC can very much be understood as a location where a discourse between contemporary American positions and contemporary European positions was undertaken and advanced.

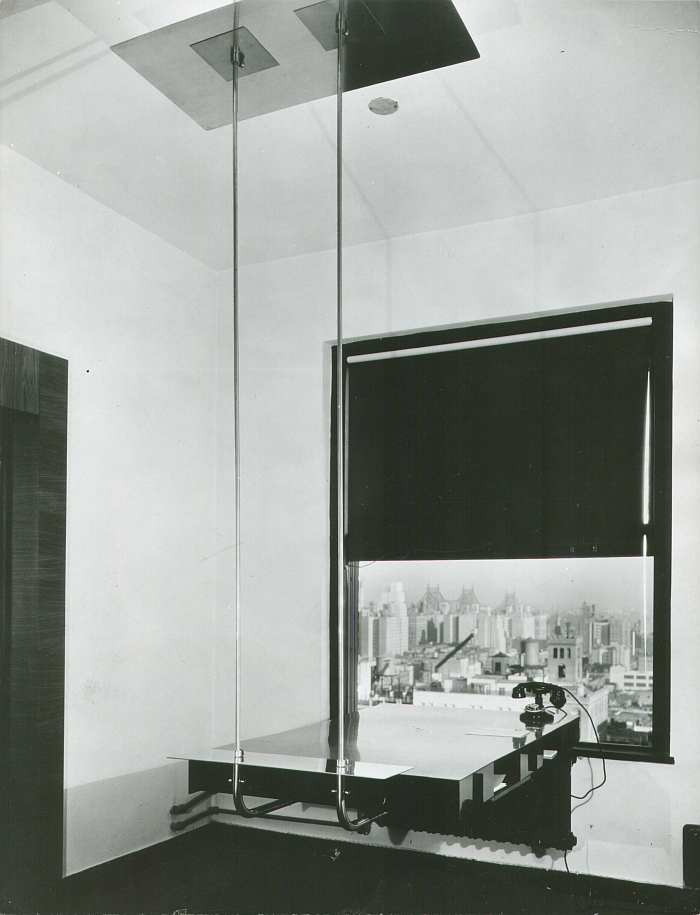

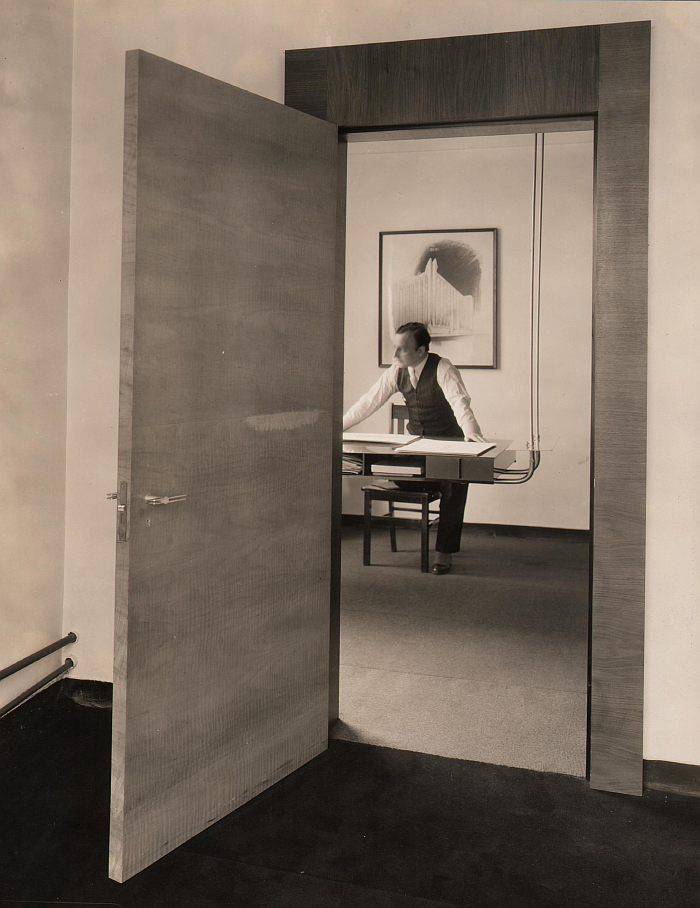

A mix of European and American creatives mirrored in the AUDAC presentation at the 1930 Home Show; a presentation which stood under Friedrich Kiesler's direction with contributions from Alexander Kachinsky, Willis S. Harrison, Wolfgang & Pola Hoffmann and Donald Deskey, the later creating a living room ensemble, while Kiesler presented an office design concept; an office which included, as the New York Times noted "a legless desk, suspended from the ceiling".24

Friedrich Kiesler's Flying Desk

A desk which doesn't fly.

That wouldn't be helpful in terms of working, desks shouldn't fly or even swing: providing stability is a desk's primary raison d'etre.

Rather Kiesler's desk was attached to the ceiling and the wall via chrome plated steel tubes, thus stabilised along two axis, an important part of the concept, and which rather than flying, hovers, floats, is very much the "flat plane suspended in space" Edward J Wormley wished for 17 years later.

An object "suspended in space" which can very much be understood in context of Kiesler's exhibtion, stage and urban planning design of the late 1920s, works in which the idea of liberating objects from the restrictions of their conventional relationship with a space, of a utilising of space rather than an occupation of space, an activation of space, an empowering of space, are very prevalent.

An object "suspended in space" which can also very much be understood in context of Kiesler's breaking of rigid compositions, opening that which is closed, challenging accepted conventions.

And although we've never actually seen the Flying Desk in the flesh, in the steel tubing and Formica, one of the many joys for us of the Flying Desk is the manner in which it divides space with out separating it, that trick we long thought the Bouroullecs had developed with their Algae; the vertical and horizontal axis very clearly create a domain "behind" it, imply a room within the room that isn't there, but you can see the non-existent walls. In may regards the Flying Desk is more an act of spatial design than furniture design, an intervention in space, very much as the Leger und Träger System or the Raumstadt were in context of exhibition design and urban planning respectively. And explodes the office in order to dissolve it into space as the Raumbühne proposes for theatre.

While whereas 1920s and 1930s tubular steel desks, as perhaps most popularly exemplified by those of a Marcel Breuer, recreate traditional wooden desks, use the steel tube to sketch the outline of a conventional desk and thereby realising a volume of space enclosed by steel tubing rather than occupied by physical wood, without ever questioning the validity of the conceptual basis of the wooden desk, were if one so will, "copies of outdated systems". Baroque desks.

Kiesler's steel tube desk does something genuinely new.

And still does.

Or could.

In an age where ever more are working ever more often at variable heights, regularly switching between sitting at a desk and standing at a desk, Kiesler's Flying Desk offers the possibility of a new approach to height variable desks25: rails in the wall, telescopic tubes from the ceiling and you can have a freely height-adjustable "flat plane suspended in space". Or perhaps more accurately a flat plane levitating in space.

Yes, that which can move vertically can also move horizontally, but Kiesler's Flying Desk is a relatively sturdy beast, it's 1930, it's Art Deco, it's showing off. Today furniture doesn't have to show off, today you can employ a much simpler, unassuming object, while new materials and technology should enable a stable, height-adjustable, suspended, wall-mounted, structure.

And why not fully height adjustable? A home office desk that when the work is done can be driven upwards and stored out the way. Or an office office desk in a space that has to serve multiple functions, and where it would be useful if desks could vanish as if into thin air. Considerations on height variability and multi-use spaces that one presumes weren't undertaken, weren't possible, weren't things, in 1930.

In addition, and what presumably also wasn't a possible consideration in 1930, is that where you have tubes coming from the ceiling you can run electricity cables through them, or internet and telephone cables, thus enabling power and services without cable spaghetti. And if the desk has power, and is fully height adjustable, and at the risk of sounding like some dangerously out-of-control 19th century patent furniture fantasists, you could also incorporate LEDs in the underside, make the underside a vast OLED, to allow it serve as a lighting feature when not a desk.

Or to paraphrase Friedrich Kiesler, it should be possible today to create an elasticity of desk adequate to the elasticity of living/working, that today's (home) office demands a vitality as is found in life. As with the Raumbühne, Raumstadt and the Leger und Träger System in their own contexts, Friedrich Kiesler delivers with his Flying Desk a very interesting, informative and important contribution as to the how.

In an earlier post we suggested Edward J Wormley's vision for a table suspended in space was "obviously ridiculous", at least in a domestic context. An opinion we herewith retract. At that point we were unaware of Friedrich Kiesler's Flying Desk, we were imagining an object fixed exclusively to the ceiling, not one that incorporated Kiesler's ingenious take on the problem, Kiesler's solution, we'll argue, reached through approaching the problem of office design as a spatial question rather than a furniture question, an approach that has lost none of its relevance or charm in the intervening 90 years. And a table suspended in space which which far from being ridiculous is a joy untold.

Similarly we suspect Edward J Wormley was imaging a ceiling bound flat plane; in his 1947 article he notes that he "once saw a legless table suspended by ropes from the ceiling", an object which "tilted dangerously if you merely touched it".26 Genuinely did fly. Which isn't helpful.

And thus leads one to presume, tends to imply, that Edward J Wormley didn't visit the 1930 Home Show, or indeed the New York office of Friedrich Kiesler's Planners Institute Inc where a, arguably the Home Show, Flying Desk was installed; however, had Wormley found the time, he would have seen not only a very probable answer to his future quest for an ideal table, nor only a very engaging interpretation of Art Deco's understandings of form, function, materials, beauty, et al but also a very concise and elegant and informative introduction to the early positions and approaches of Friedrich Jacob Kiesler, and of the inherent, and important, interplay between creative disciplines.

1Edward J Wormley, Tables Should Hang From Ceilings, New York Times, August 17th 1947, page 120

2see, Dieter Bogner and Matthias Boeckl, Friedrich Kiesler 1890-1965 in Dieter Bogner [Ed.] Friedrich Kiesler. Architekt Maler Bildhauer 1890-1965, Löcker Verlag, Wien 1988 page 9 As noted elsewhere Kiesler's early years are only vaguely recorded and so little can be claimed with 100% certainty.

3Available as the 1921 German translation by Otto Pick at https://digital.slub-dresden.de/werkansicht/dlf/367001/7 Accessed 22.09.2012

4Friedrich Kiesler, De La Nature Morte Vivante, in Friedrich Kiesler [Ed.] Internationalen Ausstellung neuer Theatertechnik. Katalog. Programm. Almanach, Würthle & Sohn, Vienna, 1924 reprinted by Löcker & Wögenstein, Vienna, 1975

5see, Gerd Zillner, Biographical Miscellanea and Nodes in the Network in Peter Bogner and gerd Zillner [Eds.] Frederick Kiesler: Face to Face with the Avant-Garde, Birkhäuser, Basel, 2019

6De Stijl, NB Internationaal Maandblad voor Nieuwe Kunst Wetenschap en Kultur, 3/4, 1923, page 359

7Barbara Lesák, Railway-Theater und Raumbühne - ein Theaterevolution von 1924 in Dieter Bogner [Ed.] Friedrich Kiesler. Architekt Maler Bildhauer 1890-1965, Löcker Verlag, Wien 1988 page 258

8Friedrich Kiesler, Debacle des Theaters. Die Gesetze der G.-K.-Bühne in Friedrich Kiesler [Ed.] Internationalen Ausstellung neuer Theatertechnik. Katalog. Programm. Almanach, Würthle & Sohn, Vienna, 1924 reprinted by Löcker & Wögenstein, Vienna, 1975

9ibid

10Friedrich Kiesler, Das Railway-Theater in Friedrich Kiesler [Ed.] Internationalen Ausstellung neuer Theatertechnik. Katalog. Programm. Almanach, Würthle & Sohn, Vienna, 1924 reprinted by Löcker & Wögenstein, Vienna, 1975

11Friedrich Kiesler, Ausstellungssystem Leger und Trager [sic], De Stijl, NB Internationaal Maandblad voor Nieuwe Kunst Wetenschap en Kultur, 10/11, 1924-1925, page 433

12Friedrich Kiesler, Mainfesto of Tensionism. Organic Building - The City in Space - Functional Architecture in Friedrich Kiesler, Contemporary Art Applied to the Store and its Display, Brentano's Inc, New York, 1930, page 48

13ibid page 54

14Friedrich Kiesler, Building a Cinema Theatre, New York Evening Post, February 2nd 1929, reprinted in Siegfried Gohr and Gunda Luyken [Eds.] Frederick J. Kiesler Selected Writings, Verlag Gerd Hatje, 1996

15ibid

16Friedrich Kiesler, Light as Architecture in Friedrich Kiesler, Contemporary Art Applied to the Store and its Display, Brentano's Inc, New York, 1930, page 118

17We are currently unable to confirm how many rooms there were, depending on source it tends to vary between 3 and 5, with probably 4 as the Mode. In addition there appears to have been a general display, which may confuse things. The answer is, we presume, to be found in the AUDAC's 1931 Annual of American Design, but we can't locate a copy of that anywhere near us. But will track one down.......

18Undated American Union of Decorative Artists and Craftsmen info flyer, Archives of American Art, Lillian and Frederick Kiesler papers, Box 40, Folder 8: Chronological, 1923, 1926, 1930-1932 available via https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/lillian-and-frederick-kiesler-papers-6310/subseries-2-2/box-40-folder-8 (accessed 22.09.2022)

19Christopher Long, Paul T. Frankl and Modern American Design, Yale Univ. Press, 2007, page 90

20AUDAC, Protection of Design, double page advert, Creative Art, Albert & Charles Boni, New York, Vol. VI, Nr. 4, April 1930, sup.-76

217lst Cong., 3d sess. H. R. 11852. Report No. 1627. In the Senate of the United States. July 8, 1930, see AN ACT Amending the Statutes of the United States to provide for copyright restrictions of design in Thirty-Fourth Annual Report of the Register of Copyrights, for the fiscal year ending June 30 1931. Available at https://www.copyright.gov/reports/annual/archive/ar-1931.pdf PDF!!! (accessed 22.09.2022)

22see Christopher Long, Paul T. Frankl and Modern American Design, Yale Univ. Press, 2007, page 90

23Members as per the undated info flyer, FN 18, which also doesn't explain how active the various individuals were, or if they were more members by association

24Home Show Ideas, New York Times, April 3rd 1930 page 57

25Judging from the available photos, Kiesler'S desk was very much floating at a conventional sitting height

26Edward J Wormley, Tables Should Hang From Ceilings, New York Times, August 17th 1947, page 120

Albeit a work that by 1947 had clearly already become the lost furniture design classic it tragically remains to this day.......