smow Blog Design Calendar: December 31st 1907 – Happy Birthday Edward J Wormley!

Caught up in the all too obvious enchantment of the likes of Eames, Nelson and Girard it is very easy to forget that post-war American design was a great deal more. It was also Edward J Wormley.

Edward J Wormley: Designs for Living

The July 1961 edition of Playboy magazine features a truly excellent article by John Anderson titled “Designs for Living”: an article which opens with a double page photo of George Nelson, Charles Eames, Eero Saarinen, Harry Bertoia, Jens Risom and Edward J Wormley. All fully clothed, one hastens to add.

Under the sub-heading “Unfettered by dogma, the creators of contemporary American furniture have a flair for combining functionalism with esthetic [sic] enjoyment”, the article explores the position that “exuberance, finesse and high imagination characterise U.S. furniture design today. For the crusading era of modern is over.”1

The six featured designers being in many respects the Knights who halted that crusade, who tamed and civilised the ravages of the so-called International Style and made modernism, contemporary design, accessible for the average American consumer.

Yet time has not remembered the six, nor their exploits, equitably, and whereas the others have become fabled household names, Edward J Wormley remains one of the forgotten men of American mid-century modern, and thus of post-war furniture design.

Which is a fate most unbefitting.

Playboy July 1961 “Designs for Living” with George Nelson, Edward J Wormley, Eero Saarinen, Harry Bertoia, Charles Eames and Jens Risom

Edward J Wormley: The Formative Years

Born in Oswego, Illinois, on December 31st 1907 Edward J Wormley was raised in nearby Rochelle, Illinois, and following his graduation from Rochelle Township High School in 1926 enrolled in the Art Institute of Chicago: an academic career which financial realities saw limited to just three terms.

Prior to enrolling at the Art Institute the teenage Edward J Wormley had undertaken a New York School of Interior Design correspondence course, thus it was perhaps more than fate alone which saw him move from the Art Institute to the interior design studio at Chicagoan department store Marshall Field & Co, and subsequently in 1930 to Grand Rapids, Michigan, based furniture manufacturer Berkey & Gay. Albeit only for a year. In 1931 Depression era financial difficulties saw Berkey & Gay fold; Edward J Wormley using his enforced unemployment to travel to Europe, where according to the popular Wormley biography, a biography which is largely devoid of referenced sources, he met both the great modernist Le Corbusier and the great Art Decoist Emile-Jacques Ruhlmann. And thus masters of two movements which were to shape his future career.

On his return to America Edward J Wormley was appointed Design Director of Berne, Indiana, based manufacturer Dunbar, and promptly set about transforming an otherwise unspectacular manufacturer into one of America’s leading contemporary furniture manufacturers. Or perhaps better put, began transforming: the war seeing him briefly seconded to the so-called Office of Price Administration in Washington where he headed the furniture division; and thus a position which, and although he only held it for two years, allowed Wormley an excellent insight into the evolving nature of both US furniture needs and the US furniture industry. And perhaps just as importantly the discrepancies between the two.

Post-war Edward J Wormley resumed his cooperation with Dunbar, albeit on a freelance basis and parallel to numerous other contracts which saw him develop a wide portfolio of furniture, textile, home accessory, wallpaper and lighting designs.

And become one of America’s leading and most highly regarded contemporary designers.

“Too little design today can compete in interest, ingenuity, and beauty with the best traditional design”

In a 1953 text Edward J Wormley opined that he can “sometimes achieve a happy result without striving to be the aesthetic pioneer or the technical innovator which I know I am not”2

Which is a little too self-deprecating for our tastes.

In texts by and interviews with Edward J Wormley throughout the 1940s and 50s he repeatedly, and very competently, states his belief in the importance of using new production methods to produce new types of furniture, of the use of standardised elements to realise more practical and cost effective furniture, of moving away from the idea of a piece of furniture as an heirloom, or of an object having only one function and towards more transient, multi-functional objects: transient, multi-functional objects which correlate with the increasingly transient, multi-functional nature of post-war architecture.

Thus demonstrating that he had not only understood the Zeitgeist of American furniture needs, but also the shortcomings of the post-war American furniture industry.

And despite his self-assessment Wormley’s responses were every bit as aesthetically pioneering and technically innovative as those of his contemporaries; where however Edward J Wormley differed from those contemporaries was in context of his views on historical models.

Pre-war American home furnishings were largely about slavishly copying historic, period styles, reproduction Chippendale, Baroque and Queen Anne being in demand, seen as synonymous with social status. The new generation of post-war designers actively sought to break with this, very questionable, tradition: it would, for example, never have occurred to a Charles Eames or a George Nelson to appropriate a historic model. Edward J Wormley saw things differently, “I have a real admiration for the design of the past and I am quite frank to say that too little design today can compete in interest, ingenuity, and beauty with the best traditional design”, he wrote in 1953, before going on to note that “there is a heritage of design fundamentals”, including ideas on proportion and emphasis, which he argues Frank Lloyd Wright, Mies van der Rohe, Gaudi and Le Corbusier have all made use of and which he refers to as “the very sinews of design.”3

Not that such should a position be seen as advocating the 1:1 reproduction of past styles, but rather of taking and making use of the best elements of previous ages and re-applying them in a contemporary context, or as Edward J Wormley writes “we must continue to work with contemporary materials, techniques and especially within the framework of our own highly developed and ever changing distribution patterns”4

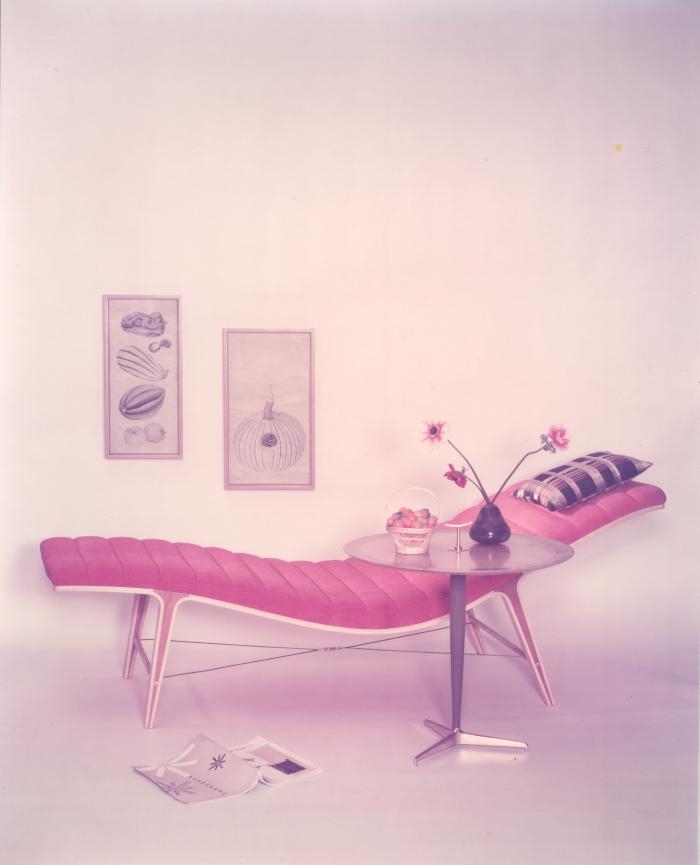

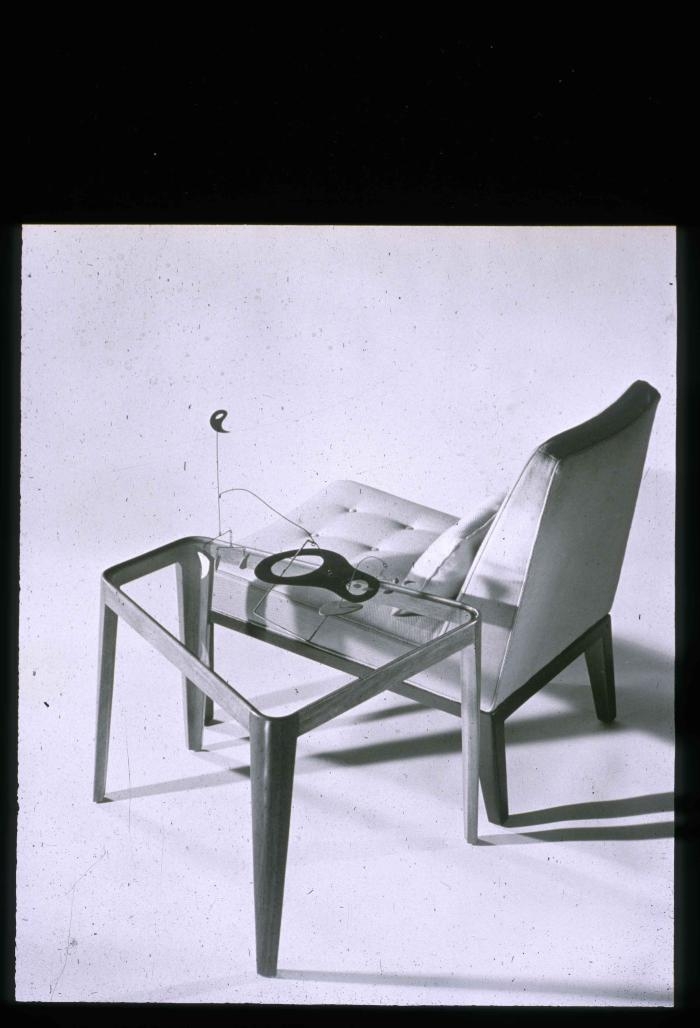

The result is a canon of work which is unashamedly classic, yet unquestionably contemporary. In the flow of the lines, the choice of materials and poise of the silhouette, Wormley’s works rarely deviate far from those of generations past, yet do so with a freshness, ease and vitality that comes from a considered and justified material and formal reduction, a reduction intended to both ease production and please the eye. Wormley’s pieces don’t have the mass of their predecessors, are less daunting, more personable, thoroughly modern, and thus were highly accessible to that, large, sector of the American public who were adapting to the changing conditions slower than many of the architects and designers of the day. Edward J Wormley offered contemporary furniture with a historical safety net.

“An ideal table would be a flat plane suspended in space”

Not that Edward J Wormley’s appreciation of the historic meant he was opposed to what his contemporaries were producing. Far from it. Writing, for example, in the New York Times in August 1947 Wormley refers glowingly to the Eames plywood chairs and storage units, noting “this marks only a beginning of the kind of thinking, call it unorthodoxy if you will, which points toward a more rational kind of design for mass production”5

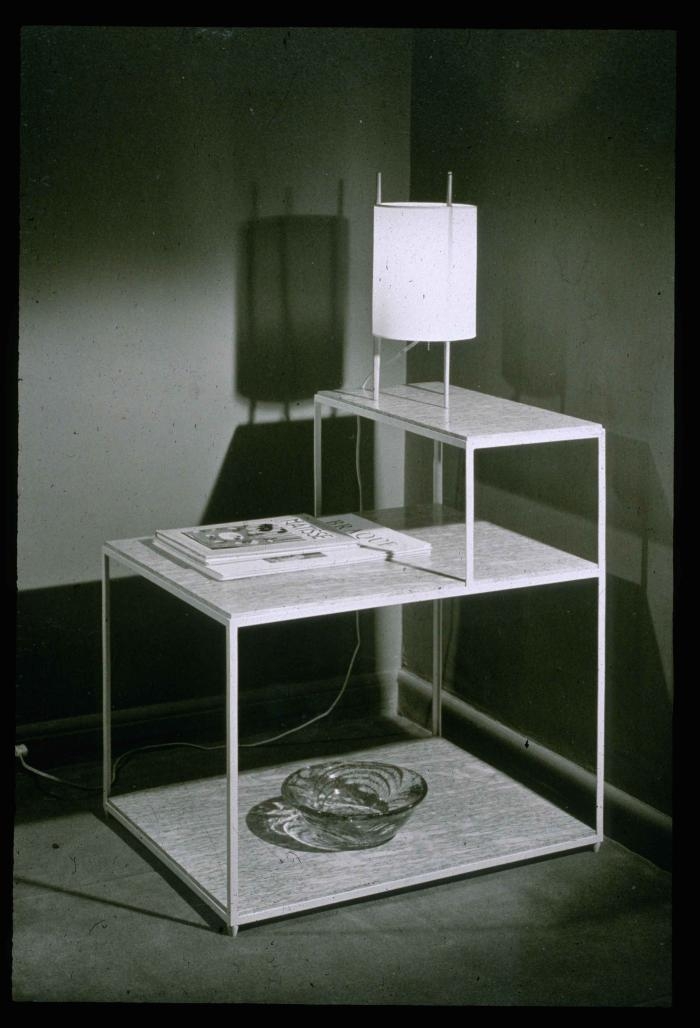

An unorthodoxy which was very much in line with Wormley’s own views on standardisation and an unorthodoxy at which Wormley in his own way was very adept. In 1947 Dunbar released a series of storage modules by Wormley which the New York Times noted was the first collection of such units they were aware of where both the front and rear side are decorated, meaning, “they do not have to stand against the wall, but can be set at right angles to it, to divide one area of a large room from the other”6 The storage unit as free-standing room divider and architectural feature rather than a solid, permanent, space stealing, entity, being not only unorthodox, but a concept which 70 years later designers continue to employ and cherish. Edward J Wormley’s ability to think outside accepted norms is also deliciously demonstrated in a 1947 article he penned for the New York Times and where he opines that “the best table is the one with the least support that will hold it steady”, or put another way, “an ideal table would be a flat plane suspended in space. It’s the legs that are the big nuisance.”7 While his solution is obviously ridiculous* – the suspension system will always be in the way, you will always bash your elbows and head against it – the assessment of the nuisance of table legs is however not only keenly made, but an excellent example of the fact that design isn’t only about answering questions, but much more about correctly understanding the question. Which Wormley clearly did. It would be ten years before Eero Saarinen arrived at the elegant, and correct, answer with his pedestal tables for Knoll.

Similarly Edward J Wormley’s work regularly demonstrates that in terms of aesthetics he was capable of being every bit as unorthodox as his contemporaries; that despite his own assertions to the contrary, he was very much an “aesthetic pioneer”.

When one, for example, compares his 1957 La Gondola sofa for Dunbar with Alexander Girard’s 1967 “Girard Group Sofa” for Herman Miller, Girard’s sofa can be clearly understood as a further development of Wormley’s design, both formally and in terms of materials; with his Tete-a-Tete Chaise Wormley created an aesthetically charming work which through a very simple trick achieves the apparent paradox of simultaneously advancing and reducing the sociability of that most common of furniture objects; while in many of his more reduced side table designs Wormley demonstrates a lightness of form that was far ahead of what many of his contemporaries were achieving.

In which context a particularly interesting object is Wormley’s 1952 Surfboard coffee table for Dunbar: Charles and Ray Eames ETR Elliptical “Surfboard” Table was released by Herman Miller in 1951. If Wormley was aware of the Eames design before starting his own or if the two designs developed independently and in parallel – Eames in California, Wormley in New York but both riding the same spirit of adventure – is unclear. Clear alone is the differing bases: Charles and Ray Eames opting for the filigree reduction of their wire base, Edward J Wormley opting for a more classic, sturdier, if every bit reduced and open, metal truss.

Edward J Wormley: The Forgotten Knight

Edward J Wormley retired in 1968, moving to rural Connecticut, living quietly and travelling extensively. Post retirement his only connection with design being a brief spell as visiting critic at Parsons School of Design in New York, an institution who in 1984 awarded him an Honorary Doctorate. Edward J Wormley died on November 3rd 1995 aged 87.

That Edward J Wormley’s legacy shines less bright than that of the other Playboy Knights is arguably on the one hand precisely because his designs were largely based on classical models: they may have been commercial and critical successes, may represent technical and aesthetic advances, but largely lack the obvious visual novelty of his contemporaries’ works. And thus arguably lack longevity in our increasingly visual world.

And then there is the fact that Wormley was Dunbar and Dunbar were Wormley. After Edward J Wormley retired Dunbar never found anyone to continue the legacy, to continue to make the company interesting and thus maintain a contemporary interest in Wormley’s works. A situation exacerbated by the fact Dunbar ceased trading in 1993: with no-one to produce Edward J Wormley’s works they, and he, quietly slipped from popular memory.

Which is a shame, arguably even a crime, because despite its conservative, historical roots Edward J Wormley’s work remains today every bit as contemporary as the works of Saarinen, Bertoia or Risom, and embody in their construction, form and conceptual, theoretical origins the revolution and élan of post-war American furniture design every bit as elegantly and competently as the work of Eames or Nelson. Are uncompromisingly modern. And unapologetically classic. Or as John Anderson, somewhat over-confidently, put it: “But it is the figure of Edward Wormley that best epitomises designs for living in the modern movement.”8

As with all designers from time to time Edward J Wormley got it monumentally wrong, as in monumentally, and wandered down dark alleys where he should have known there was nothing but trouble waiting; however, in the vast majority of his works, and also in his writings, he exists as a self-confident representative of an understanding of furniture design which isn’t about satisfying commercial demands or responding to perceived markets and changing “tastes”, but of furniture design as an evolution in response to changing needs, social, economic and cultural conditions and for all as something which comes from the designer, something which represents the designer’s honest response to the ever changing realities. And thus left us with a canon of works which extends and enriches the (hi)story of post-war American design and the American furniture tradition.

Happy Birthday Edward J Wormley!

At this juncture we’d like to express our sincere gratitude to the Archive Team at the New School New York for the quick, friendly, uncomplicated manner in which an agreement was reached on using the photos in their collection to illustrate this post. Thank you!

* In the interests of fairness, Edward J Wormley was also active as an interior designer, and such a suspended system has potential advantages in a display context, so in a museum, gallery or even a shop. Arguably even in an office environment. But in a domestic environment…. ridiculous.

1. John Anderson, Designs for Living, Playboy Magazine, Chicago, July 1961

2. “Contemporary Furniture Designers: William Armbruster, Edward J Wormley, PaulMcCobb, Charles Eames, Robin Day, and Hans Hoffman” in Everyday Art Quarterly, No. 28, Contemporary Furniture Designers and Their Work, Walker Art Center, Minnesota, 1953

3. “Contemporary Furniture Designers: William Armbruster, Edward J Wormley, PaulMcCobb, Charles Eames, Robin Day, and Hans Hoffman” in Everyday Art Quarterly, No. 28, Contemporary Furniture Designers and Their Work, Walker Art Center, Minnesota, 1953

5. Edward J Wormley, Tables should hang from ceilings, New York Times, New York, August 17th 1947

6. Mary Roche, Utility stressed in furniture line, New York Times, New York February 10th 1947

7. Edward J Wormley, Tables should hang from ceilings, New York Times, New York, August 17th 1947

8. John Anderson, Designs for Living, Playboy Magazine, Chicago, July 1961

Edward J Wormley. Tiered End Table (with Model 9 Table Lamp by Isamu Noguchi for Knoll). 1945. (Photo: Edward J Wormley papers; Professional (KA0048.02). New School Archives and Special Collections Digital Archive)

Tagged with: Dunbar, Edward J Wormley