In 1949 Edgar Kaufmann Jr. the, then, Director of the Industrial Design Department at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, reflected, not uncritically, that "as more and more new chairs become available to the buying public, the problem of selection begins to be bewildering." A truism that has lost nothing in contemporaneousness over the decades; and also a very nice eyewitness observation from the early days of the rise of the post 1939-45 War American furniture design industry. And of its associated, parasitic, mimics.

"Is it true", Kaufmann asks, in context of his reflections, "that our needs are so varied?"1

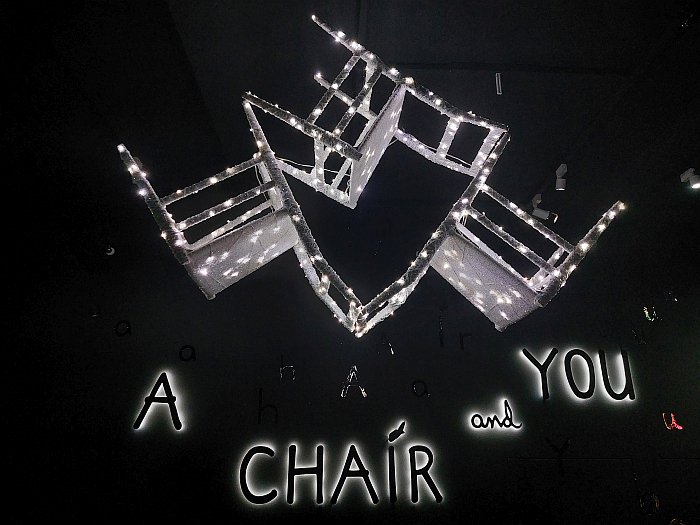

Just one of a great many questions of chairs, seats, sitting and sitters A Chair and You at the Grassi Museum für Angewandte Kunst, Leipzig, encourages, empowers, you to reflect upon.......

In many regards A Chair and You has its origins in the 1990s where and when Swiss entrepreneur Thierry Barbier-Müller began collecting chairs, A Chair and Thierry Barbier-Müller, if you so will. A Chair and Thierry Barbier-Müller that over the next 30ish grew to some 650 Chairs and Thierry Barbier-Müller and which occasionally became A Thierry Barbier-Müller Chair and Musée cantonal de design et d'arts appliqués contemporains, Mudac, Lausanne, when the later borrowed works from the former's collection for their exhibitions; contact between Thierry Barbier-Müller and Mudac which very naturally led to the question of the possibility of an exhibition of Barbier-Müller's collection, whereby, as Chantal Prod'Hom, Mudac's former director, and a key protagonist in the development of A Chair and You explains, simply presenting the chairs in groups on pedestals wasn't really an option. Was way to obvious an option to be conceivable.

And then Robert Wilson entered the discussion, a creative who for all he is most popularly known as a theatre director has a biography that encompass painting, sculpture, light design, scenography, etc, etc, etc; a creative biography which, in many regards began with architecture studies at the Pratt Institute, Brooklyn. A Robert Wilson who had known Thierry Barbier-Müller and his collection for a great many years. And, as one learned at the opening of A Chair and You, a Robert Wilson with a long (hi)story of and with chairs: not only are several of his designs in Barbier-Müller's collection, and in A Chair and You, but as a child in Texas he, by his own account, used to regularly move chairs away from the wall where they invariably stood and set them in space. Chairs, Wilson reflects, are lines, shapes and colours in space.

Which is essentially what A Chair and You is.

An arrangement of lines, shapes and colours in a space that Robert Wilson and his team approached, as Wilson, by all accounts, approaches all his artistic works, from detailed considerations on first of all light, sound and space and then, at the end of the process, the objects; a starting with the light Wilson learned in a lecture from the architect Louis Kahn during his student days in Brooklyn. And a process that is diametrically juxtaposed to how museums and curators normally work, with the object at the forefront of their thoughts and around which all other elements are constructed and defined.

Thus a process that not only produces a presentation that more conventional approaches simply couldn't, but which allows for a unique environment in which to reflect on chairs, seats, sitting and sitters.

Unique in all senses.

Sensorially unique.

Arranged as a succession of rooms, much like the spatial construction of Alice's journey through Wonderland, which is not the only comparison that can be made to Alice's time down that particular rabbit hole, A Chair and You is as much a Robert Wilson installation as an exhibtion, or perhaps better put, as much a Robert Wilson choreography as an exhibition; a movement of and through lines, shapes, colours, light, sounds, emotions that carries you from scene to scene, that continually resets the relationships between viewer and exhibit. A choreography of spaces that initially gets ever darker, then ever brighter and which ends in the Orangerie in a presentation that is so bright it's dark. Is simultaneously the brightest and darkest space of A Chair and You.

If a journey the linear geometry of the Grassi Museum temporary exhibition halls means that you have to undertake twice, you have to retrace your steps, which while not, we suspect, ideal in context of the concept, whereby we didn't see it on its first presentation in Mudac and so are guessing, does provide you with a physically dark space in which to calm down a little after the Orangerie, which, believe us, you will need to do. And also gives you the opportunity to spend more quality time with the works on show, and there are a lot of engaging and rarely met chairs to be enjoyed and conversed with: Barbier-Müller's collection is primarily objects from small series, one-offs, and prototypes, and contains a great many expressions of post 1939-45 War positions that challenge not only the established conventions of seats and seating but for all challenge the conventions, and creations, of Functional Modernism, there are a lot of subtle and obvious, skilful and obvious, cheeky and obvious, plays with the themes, positions, materials, solutions, certainty, reputation, future of Functionalist Modernism.

Or put another way, you'll not find any of those ubiquitous examples of the popularly understood highpoints on the helix of furniture design (hi)story, those 'classics' that so unquestioningly populate design museums and that one finds in lazy coffee table books and even lazier social media feeds. But you will find an awful lot of very interesting and informative works, one could even argue a few seminal works. But nothing that would be popularly termed a 'classic'. And as such A Chair and You is a further invitation, alongside Horst Heyder's EW 1192 as met in Der ungesehene Designklassiker at the Deutsches Stuhlbaumuseum, Rabenau, to reflect on that much overused, misused, term. And to reflect on the consequences of such unthinking, unreflective, behaviour on our relationships with chairs and interiors.

As an installation, a choreography, as much as an exhibition A Chair and You is devoid of much of the paraphernalia of exhibition design: there are, for example, no signs to read, no videos to watch, charts to be digested, there aren't even name tags for the individual objects2; rather A Chair and You is a chair. And you. An invitation to try to establish a relationship with a chair, with ca. 140 chairs, you in all probability know nothing about, have no external aids to locating and approaching, no crib notes with which to begin a dialogue, no biography to delve into. It's a chair and you. And that in a space that is as sensorily stimulating as it is discombobulating. And it's very discombobulating. We can bring you pictures, but not the sounds. Nor the changing light. Nor the sounds.

And as such despite being a public installation, a mass choreography, each and every viewing is a unique private, personal experience

Is about chairs and you.

Chairs and Thierry Barbier-Müller.

Chairs and Robert Wilson.

Chairs and Edgar Kaufmann Jr.

Chairs and us.

Chairs from which show we spent a lot of time with, and amongst many others, Marijn Van der Poll's 2000 work Do Hit Chair, not only an ever glorious example of why droog design are, were and always will be so important, but also a hewing of dimensionless space into a utilitarian form that provides so many perspectives on the relationships between human society and the environments we occupy; Grand confort, sans confort, dommage á Corbu by Stefan Zwicky essentially an LC2 by Le Corbusier, Pierre Jeanneret and Charlotte Perriand cast in concrete and steel reinforcement bars that amongst the myriad other thing it is, is, in its eternal permanence, its intransformability, a delightful comment on the musealisaton of furniture; Isamu Noguchi's Pierced Seat, a work difficult to spot in the Dark Space, but a Noguchi who in many regards learned about objects and space, objects in space, objects and space in communication, in context of his stage designs for the choreographer Martha Graham, thus an apposite reminder of the links between the performing arts and the applied arts that A Chair and You plays with, and a Martha Graham for whom, as noted from Isamu Noguchi at the Museum Ludwig, Cologne, Noguchi created a chair that is "the great lost Noguchi furniture design", a work even more in the shadows than Pierced Seat; Ettore Sotttsass's Tappeto Volante, a work with humour and respect and admiration and observation and empathy which reinforces the poetry that a Sottsass was capable of, and why reducing him to Memphis is so foolhardy. Or Hiroko Shiratori's Discipline Chair, an object that requires the control and self-discipline and active contribution of the sitter in order for it to function as a chair, and which when you provide that, we'd imagine, allows for one of the freest and most comfortable of sitting experiences imaginable. But which is inconvenient and impeding if you refuse to provide it. Which, yes, is almost certainly a metaphor for life. And a conformation of the lie inherent in the much repeated mantra of the libertarian and the hippy.

And a Hiroko Shiratori who is, by our math, one of only around 10 females presented amongst the 140 works; that some of the males are present with more than 1 work there are less than 130 male designers present, but only marginally less, and certainly wildly more male designers present than the 10 females. It's probably, we'd guess, around 10% female. Numbers which allow one to, force one to, reflect on the why that should be? Is the ratio in A Chair and You representative of the collection as a whole or has the selection for A Chair and You a male bias? And if it has a bias, why? And if it is representative of the collection, why? Whys that, we suspect but don't know, in all probability have less to do with how Thierry Barbier-Müller collected, although that may, and as similarly discussed in context of the collecting practice of Karl H. Bröhan from Regard! Art and Design by Women 1880–1940 at the Bröhan Museum, Berlin, have something to with it, and is more related to and reflective of the realities of access to the design gallery and one-off industry in post 1939-1945 War Europe, certainly in the immediate post-War decades. Access that while arguably easier than access to the commercial industry, was, over a great many years, anything but equitable with that afforded to males. For all the male architect who richly populates A Chair and You and who has long occupied a hallowed place in the Pantheon of Design.

Thoughts and questions which remind that any exhibition can always be viewed, should always be viewed, must always be viewed, in many more ways than the curators intended. An exhibition is but an invitation from the curators.

Even an exhibition as singularly curated as A Chair and You.

A theatrical staging in all senses, and for all senses, except, regrettably, tactilely, A Chair and You could very easily have slipped into the contemporary 'experience' that so often stands surrogate for the museum visit in our increasingly visual society with its aversion to words and its inability to concentrate on one subject for longer than a TikTok video; but deftly manages to avoid such a fate. And that not least because its focus isn't on providing an experience but on presenting chairs as an experience: the chairs are always at the centre of what is happening, and that despite, or perhaps exactly because, Robert Wilson and his team considered them after the light, sounds and space that seem to be in the foreground. But which are actually in the background. A classic theatrical use of smoke and mirrors to build extra layers into, and add a tangible tension to, the narrative and the performance.

An installation, a choreography, a theatrical staging that doesn't take itself all too seriously, it lets you know it understands the arts it is practising, that it masters them to a high degree, but knows that there are more important things in life than practising such arts. In addition there are some very nice self-deriding touches including, for example.... no...no... no spoilers here, discover them for yourselves. Yes, at times it is self-indulgent. But we'd argue deliberately so. Is, we'd argue, openly playing with the self-indulgence of the furniture industry, the self-indulgence of the architecture and design professions, the self-indulgence of art historians, the self-indulgence of critics, the self-indulgence of the design gallery gatekeepers, every bit as much as many of the works subtly, skilful, cheekily and/or obviously play with the themes, positions, materials, et al of Functionalist Modernism, a period still considered sacred in many quarters, despite its flaws and dangers being increasingly indisputable. For us the presentation carries itself very much as a caricature of one of those ubiquitous individuals in the furniture/design/architecture/curatorial world who have a dangerously over-exaggerated sense of their relevance and importance and knowledge. Who believe their own PR. And who won't recognise themselves in the caricature because they lack the all important self-refection. And who certainly won't read the catalogue.

And an installation, a choreography, a theatrical staging that once you move beyond the self-indulgence, the playfulness, the lights, the sounds, the spaces, the show, reveals itself as a very rational and sober presentation that enables, demands, you to view rooms full of chairs more intently and judiciously and in more exacting detail than you normally would, arguably ever have. Or ever will again. And not only demands you view rooms full of chairs, but that you listen to the discourses and debates between the chairs in those rooms, conversations you've probably never heard before, never knew took place. Demands you follow, question and reflect upon not only the recurring materials and constructions, but also the recurring similarities in position, approach, comment and challenge inherent in many of the works, including, for example: resistance, defiance, chairs that actively refuse to be sat on; or sensuality, chairs that play with the intimate physical relationship between seats and the seated: or power, empowerment, the chair has long been a symbol of power, the throne being without question the most popularly know example, but what is power? How is power? Why is power? Who is power? What could power be?

Allows, demands you, to question why such an apparently endlessness of possibility in an object that is apparently so simple, why the "bewildering" selection of chairs not only in A Chair and You but in contemporary society?

"Is it true that our needs are so varied?"

???

In many regards not, in essence our needs are all identical, and are exactly the same in 2024 as they were in 1949: water, food, love, punk rock.

Society has however become ever more complicated: late 1940s America appearing in the social and cultural rear-view mirror to be an astonishingly simple society, almost impossibly so, in comparison to the interlaced multilayered intrinsically unstable early 21s century.

And as society has become more complicated chairs have been our ever present chroniclers, documenters, mentors, scouts and motors. As they always have been. Chairs have always charted, accompanied, supported and driven developments in human society; one thinks, for example, in context of European society, and staying deliberately on a relatively mainstream path, the rise of the Windsor Chair in the 18th century, over the work of a Michael Thonet, a Heinz and Bodo Rasch, an Alvar and Aino Aalto, a Charles and Ray Eames and onwards to today. Yet whereas in centuries past the worlds in which chairs were to be functional were defined by a limited number of discrete parameters and planes, as was 'function', such is no longer the case. What is the 'function' of a chair today?

Form may or may not follow function, but what is the 'function' of a chair?

A question that began to be posed in the 1960s from which many of Thierry Barbier-Müller's earliest pieces originate; and a question which has been expanded and refined and challenged and reframed by designers ever since. Always in context of the wider social, cultural, economic, ecological, technological, et al realities

A state of affairs that means if a Edgar Kaufmann Jr. with all his experience and learning thought things were bewildering in 1949 he'd be lost today.

A today in which chairs are only rarely primarily about a physical form. Which is always worth telling Plato. He'll not understand, but let him try and argue that your wrong. Thierry Barbier-Müller would understand, one can see that in his collection, in the why of his collection that can be read through viewing A Chair and You. Robert Wilson understands, his installation making clear that while chairs are without question lines, shapes and colours in space, Wilson understands that is not the whole story, there is a lot more. Plato however wouldn't understand. Couldn't understand. And not only Plato would have difficulty understanding. An Edgar Kaufmann Jr. would, as implied above, have problems. As would, do, a great, great many of the contemporary "buying public", or rather 'consuming public', another important change since 1949. A 'consuming public' conditioned by the 'classic' on the pedestal approach to public discourses on chairs. A popular public discourse that routinely ignores the seats, sitting and sitters that A Chair and You understands needs must be included.

And pleasingly and satisfying does so in an installation, a choreography, a theatrical staging, a landscape, a rabbit hole, a Wonderland, a discombobulation of sound, light, space, a multi-faceted conversation between similarly disparate objects, an exhibition that to not only invites you develop and tune your appreciations of and positions on seats, sitting and sitters as well as on and of chairs, but also invites you to reflect in more detail on the myriad complex relationships between that on which we sit, the act of sitting, and the spaces material and immaterial within in which we sit.

To reflect on, and to begin to better appreciate, the myriad inextricable relationships between a chair and you, between chairs and us.

And to better appreciate that while there are unquestionably today, as in 1949, far, far, too many chairs, there is always a need for a great, great many more. And always will be.

A Chair and You is scheduled to run at the Grassi Museum für Angewandte Kunst, Johannisplatz 5–11, 04103 Leipzig until Sunday October 6th.

Full details can be found at www.grassimak.de

In addition The Spirit of the Chair a richly illustarted bilingual French/English catalogue of Thierry Barbier-Müller's collection is available via Lars Mueller Publishers, Zürich.

1Edgar Kaufmann Jr., The Profusion of chairs: Four simple rules guide buyers faced with perplexing choice, New York Times, September 25th 1949, page XX13

2There is however a small booklet which lists all the works, much as a theatre and opera programme provides the necessary background information to that which on the stage unfolds