For all that any interior space is predominately air, air is essentially ignored in architecture, plays no role in the work of architects.

Not so in the architecture of Hans-Walter Müller.

With Monsieur Luftarchitektur – Hans-Walter Müller. Architekt, Ingenieur, Künstler; 1967 bis heute the Luftmuseum, Amberg, allow for an introduction not only to Hans-Walter Müller, but to the pneumatic architecture of his practice.......

Born in Worms on December 25th 1935 as the son of an architect, Hans-Walter Müller decided early on to follow in those paternal footsteps, and that, as he later commented, as the result of a fairly simple decision process, "ich habe einfach das gewählt, was mein Vater gemacht hat!"1, 'I simply chose to do what my father did!'

Whereby, as Monsieur Luftarchitektur – Hans-Walter Müller. Architekt, Ingenieur, Künstler; 1967 bis heute neatly elucidates, he very much didn't. But we'll get to that. First things first.

A decision to follow in his father's footsteps that took him in 1955 to the Technischen Hochschule Darmstadt, and not only a Diploma in Architecture and Urban Planing, but also to periods working in various architectural practices, including assisting Ernst May with the development of the Mainz urban redevelopment scheme, and to the maturation of a childhood fascination with magic to a professional practice in magic: Müller partly financing his studies through magic shows, regularly travelling throughout the West Germany of the late 1950s to perform, often under the name Petrini, which may or my not be a reference to the 17th century architect Antonio Petrini whose work includes the main gate of Mainz Citadel.

And a decision that subsequently took him in 1961 to Paris where a scholarship enabled him to continue his studies at the École des Beaux-Arts. Not that, by his own admission, he spent much time at the École des Beaux-Arts; rather he attended lectures by Jean Prouvé at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Métiers, worked in various architectural offices, immersed himself in the international architecture and artistic communities of early 1960s Paris, worked as a magician in a Cabaret in the Quartier Latin, trained as a mime under Étienne Decroux. And also began experimenting with kinetic art for all kinetic art involving projections; Hans-Walter Müller developing a variety of projects, a variety of projecting machines, throughout the early 1960s, including Genèse 63, a work, a machine, we've never seen in action, but which Müller describes as creating 'architecture with light' and which enabled one 'to change and transform a space through projections'2. Thus a work, without having seen it in action, that would appear to echo the light experiments at the Bauhauses of a László Moholy-Nagy or a Ludwig Hirschfeld-Mack.

A Genèse 63, and an ever increasing reputation in the Paris art world of the mid-1960s, that saw Müller invited to participate in the 1967 exhibition Lumière et Mouvement at Musee d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, an exhibition that also featured the likes of Martha Boto, Jean Tinguely or Victor Vasarely; and a 1967 exhibition, and reflections on 'architecture with light' and the ability 'to change and transform a space through projections' which led, more or less directly, to his first inflatable structure, his first, as he terms his inflatable structures, Volume: Volux - Vol(ume) + Lux.

A Volux first displayed in context of the 1968 exhibition Structure Gonflables at the Musee d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, an exhibition that, as the title implies was concerned with inflatables both decorative and utilitarian; a Volux in the form of periscope, measuring some 6 metres in height, 3 meters in diameter at the base, 5m long at the top, which inflated and deflated in constant loop, was fitted out with loudspeakers and within which several projectors were running. A work that in contrast to that which would come wasn't accessible rather was viewed from outwith.

And early experimentations with structure gonflables that from there, for want of a better phrase, expanded.

An expansion that saw him move ever further away from the "was mein Vater gemacht hat" he'd once chosen to do.

An expansion that can be approached in Monsieur Luftarchitektur.

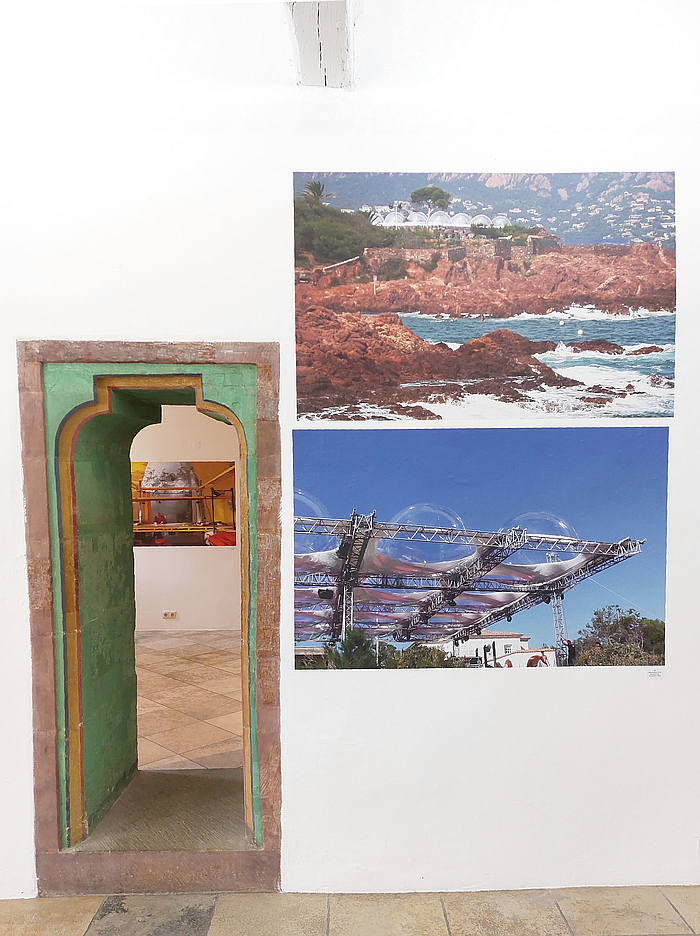

Primarily a photographic exhibition Monsieur Luftarchitektur presents projects from across the years and contexts of Hans-Walter Müller's practice that elucidate what he has done that his father didn't do, be that, for example the Volume Centre commercial which between 1982 and 1984 served as a 1600 sqm metre supermarket in Sarcelles, to the north of Paris, while the surrounding Place de France was redeveloped; the volume Chaillot II for the 1997 Le printemps en hiver sales presentation staged by Parisenne parfumerie Marionnaud, a volume that also helps elucidate the importance of commercial commissions in Hans-Walter Müller's career; or the volume Belvédère realised at Hans-Walter Müller's base in La Ferté-Alais to the south of Paris that serves as a space for workshops and also for accommodating visitors and guests. And also, let's say non-architectural works, works that aren't in themselves buildings, including, for example, the scenography for the 1986 production of the ballet Malraux ou la Métamorphose des by Maurice Béjart in Brussels; a sadly unnamed and undated collection of columns that is very clearly installed as an artwork in a foyer; or his Ballon transportable, a, as the name implies, sphere within which Müller sat on a small moped and drove through Paris in context of World Environment Day 1998.

Photos that also elucidate the work and processes that are involved in creating his Volumes, processes that as the exhibited photos allow one to appreciate are undertaken on the computer as much as on the sewing/high-frequency welding machine, all Volumes being designed by Müller and constructed by Müller and his team; and photos that also elucidate aspects of the how Müller achieves his single-wall Volumes, how he creates his pneumatic architecture, while not giving away any real technical secrets.

And photos that also help explain that since 1973 Hans-Walter Müller has lived and worked in an inflatable structure, that for over 50 years he has lived by example.

Specifically, since 1973 Hans-Walter Müller has lived and worked in the Volume M210 in the aforementioned La Ferté-Alais, a two-storey structure — the ground floor is technically an underground floor, and does involve traditional construction materials such as brick, concrete, wood, etc, with an inflated first floor above it. An M210 that replaced a couple of smaller predecessors: the first, M from 1971, the second the so-called Petite Maison from 1972 that Müller had pitched as a holiday home concept before living in it himself, and that, as one can see in Monsieur Luftarchitektur contained within it an open-fire place which, along with the many functional features of M210, tend to demonstrate that the nature of the construction principle brings with it no real limitations regarding its use, that is simply a question of the ability of the responsible parties to think their way past the challenges. Which arguably is the role of any architect. Of all architecture.

Photos that, yes, means one can't physically experience the spaces Hans-Walter Müller has created, can't experience them on and through your own body; but on the one hand given the very real physical limitations of Amberg's Luftmuseum ¯\_(ツ)_/¯. And on the other is an excellent example of the classic problem of presenting the architectural scale at the room scale.

A problem Monsieur Luftarchitektur tackles with a video portrait of Müller in which he comes to word and in which various of his projects are featured, including a detailed look inside M210, and with a silent video of further projects in action, that neatly expand on the photos. And also by two models, one, a sadly unnamed Volume, which inflates and deflates on constant loop much as that 1967 Volux did, albeit without the loudspeakers and projections, which may or may not be a trick missed in the conception of the showcase, and a second model that sadly wasn't inflated on the day we were there, but which when inflated, we're certain, will help reinforce and extend the impression given by the model we did see.

If, and for all the models and films help extend the photos beyond their 2 dimensionality, and thus help extend the narrative, a few more models and plans would have been very much welcome.

And on the rare, and thus all the more valuable third hand, for all that Monsieur Luftarchitektur is without question about the projects and about Hans-Walter Müller, it is also very much about pneumatic architecture as a genre of architecture.

A genre, an approach, that although it can be traced back to the first decades of the 20th century, can be linked to the development, to the rise... Sorry!!!... of airships, arguably first became popularly visible, and popularly plausible, in the 1960s Hans-Walter Müller began experimenting with it. A genre, an approach, that throughout the Radicalism of the 1960s and 70s in all its hues and dialects was a regularly employed approach for expanding... Sorry!!!... the discourse on what architecture was, what architecture is and what architecture could be. One thinks in particular of the work of the likes of a Haus-Rucker-Co, a Coop Himmelb(l)au, a Frei Otto, or a Hans Hollein, the latter perhaps most tangibly, and deliciously, via his ever genial 1969 Mobile Office project.

Whereby in our reading of Hans-Walter Müller's practice, which may be incorrect, and we've never asked him, we're not seeing any direct influence from such practitioners, okay possible from a Frei Otto, there is inarguably a two-way influencing of and from a Frei Otto whom Müller had known since the earliest days, was in regular contact and with whoms practice one can trace numerous theoretical tangents; rather, for us, Hans-Walter Müller's practice is located solely in Hans-Walter Müller's experiences of and experimentations with light, space, mime, magic, kinetic art et al and their influence on his positions as to what architecture was, what architecture is and what architecture could be. Which is arguably what make his contribution to the discourses on what architecture was, what architecture is and what architecture could be all the more instructive.

And a genre, an approach, that wasn't just limited to architecture, but rather that in the 1960s/early 1970s was embraced by creatives of all hues, including furniture designers such as, for example a Paolo Lomazzi, Donato D'Urbino and Jonathan De Pas as most popularly represented by the trio's 1967 Blow armchair, a Quasar Khanh as exemplified in his 1968 Aeropsace collection or a Verner Panton whose inflatable stool from 1960 doesn't have the popular fame of many of his other works, but does help explain more convincingly than those other works that Panton was often ahead of the avant-garde; toys including a Libuše Niklová's menagerie of animals from the 1960s and 1970s; and also the art of, for example, the Utopia collective who organised the aforementioned exhibition Structure Gonflables, a Claes Oldenburg, a Jeff Koons or an Andy Warhol, the latter whose 1969 Silver Clouds installation can be seen in a photo from 1970 in Monsieur Luftarchitektur floating within Müller's Volume Théâtre expérimental for Fondation Maeght in Saint-Paul-de-Vence on the Côte d’Azur. A photo that, for us, neatly encapsulates the fascination with air at that period, the promise air spoke at that period: pneumatic art in a pneumatic building for a society of limitless horizons.

A list of creatives who highlight the somewhat unfortunate linguistic incongruity of the location of inflatables in Pop Art and Design.

And a fascination for inflatables amongst creatives of all hues that in the course of the 1970s didn't so much pop, as slowly deflate.

The work of a Hans-Walter Müller elegantly making an argument for a reinflation.

An argument made on the one hand through the physical of the works in themselves.

For all that a Hans-Walter Müller decries descriptions of pneumatic architecture as makeshift, as temporary, argues stridently against any attempt to discuss pneumatic architecture as makeshift, as temporary, the concept of mobility and transience inherent in many of his Volumes does allow for practically conceivable solutions in that direction. Something very much inherent in Müller's first publicly accessible Volume, L'Église gonflable realised in 1969 in Montigny-lès-Cormeilles to the north-west of Paris: a church that was inflated in 10 minutes, in which some 200 worshippers could, did, celebrate Mass and which could be rolled to a pack under 2m long, weighing just 39 kilos.

The advantages speak for themselves. And speak of uses of pneumatic architecture as mobile and transient.

Be that, for example, in emergency accommodation contexts, a lorry load of such structure providing quick and secure initial shelter for a small community; or in context of events, trade fairs, festivals et al where similar structures are needed in various locations at different times, see also the aforementioned Chaillot II as a presentation space for Marionnaud that was subsequently employed in, subsequently reinflated for, commissions from Électricité de France and SNCF, and the associated thoughts on the trade fair architecture of the early 20th century where buildings were constructed in brick, concrete, wood, etc, and then demolished once the party was over.

Or one thinks of a Hans Hollein's aforementioned Mobile Office, the ability to carry the space you need with you; or in a world in which ever less available land must be used for ever more purposes Volumes allow regular switching of buildings rather than the creation of a permanent multi-purpose building that often isn't, or not without problems, and extra costs. And which in many regards brings us back to events, trade fairs, festivals et al.

Not that pneumatic architecture must only be mobile and transient, it can also be as permanent as architecture in brick, concrete, wood, etc, Architecture Gravitaire as Hans-Walter Müller refers to it. Permanent structures such as the M210 Hans-Walter Müller has called home for over 50 years and which as a hybrid offers a model of a possible future for housing: a constructed base/cellar upon which a Volume is inflated. With the possibility of adding additional Volumes, including function specific Volumes, as and when required. And of removing Volumes as and when required. A variability, a modularity, that Müller has enabled since the earliest days via integrated ports that allow various Volumes to be linked, the aforementioned Chaillot II being a particularly elegant example. A permanence with effortless variability that is a further reinforcement of the strong argument that permanence is best achieved via flexility rather than rigidity. Be that in architecture, society or your own life.

And why stop at single houses. Why not apartment blocks of Volumes that can be freely adapted as needs demand. Schools that be expanded or reduced, hospitals that can expanded or reduced, factories that can be expanded or reduced, office blocks that can be expanded, reduced, changed in function simply through adding, removing, switching Volumes?

Why not replace the construction industry with an inflatables production industry who sell and/or rent Volumes?

Yes, we hear you, and you're right, there is the need to constantly power the pumps and fans to keep it all inflated. That is true. No-one is contradicting you.

But on the one hand we're not going to take lectures on the responsible use of energy from anyone who insists on owning an autonomous vacuum cleaner, an autonomous lawnmower, a smartwatch, earpods, tablet, electric car, electric bike, two smartphones, and all the other de rigueur accoutrements of contemporary life that require constant charging, and who want their groceries delivered by electric drones. And on the other, the contemporary construction industry, for all a contemporary construction industry based around a position of Remove. Rebuild. Repeat, is a very active annihilator of resources, is responsible for the greater part of the global energy and resource usage of contemporary society. Pneumatic architecture may use less resources over time than current conventional practices. We don't know, we've not seen any data, such data may not exist, but it would be interesting to compare the resource usage of a school, a four bedroom house or a small town with its endless construction work, over say 20 years. Which is the most resource efficient model?

A comparison that also involves the question of how one powers those pumps and fans.

Sadly, unless we missed it, not included in Monsieur Luftarchitektur are photos of Müller's 1975 shelters for the homeless in Paris, Volumes that were inflated from the air flows from the metro and the warm air vents of the city, and thus stand not only as an example of a use of pneumatic architecture beyond that which conventional architecture can offer, but a model of a possible system for integrating Volumes into urban spaces with a minimum of resource footprint. That uses those airflows any and every city produces and wastes.

And what if you powered those pumps and fans with renewable energy?

While there is something particularly satisfying about using wind turbines to generate the power for the pumps and fans, there is invariably something much more practical in employing solar power, for all if the solar cells can be incorporated in the skin of the Volume.

Which, yes, brings us to the, invariably, oil based synthetic plastics of Hans-Walter Müller's Volumes.

A material that in the 1960s Hans-Walter Müller had no choice but to use, and which, lest we forget, was then a future focussed material that would solve all our problems before the problems it brought with it saw it become a future endangering material. Today we have alternatives, and if we decided to follow a path of pneumatic architecture we can focus research on the targeted development of novel materials that are as robust and durable as the oil based synthetic plastics. And that can allow solar cells to be incorporated.

And if we can create low footprint inflatables from novel materials, and, potentially inflated with the aid of novel, highly efficient, pumps and fans, what is then your argument against?

Probably one of aesthetics, a disquiet at the thought of the necessary changes in the visuals of the built environment enforced by pneumatic architecture.

Which isn’t an argument, it's not. But does bring us to the other component of the argument for a reinflation of pneumatic architecture made by the oeuvre of Hans-Walter Müller: the theoretical.

A theoretical that is very much inherent in Hans-Walter Müller's practice; much as theory was the raison d'etre of the Radical pneumatic architecture of the 1960s and 70s, that pneumatic architecture that existed parallel to Hans-Walter Müller's earliest experiments, but we'll argue, isn't directly related, so to is Hans-Walter Müller a theoretician as much as a practising architect. His works not only having an interior and exterior separated by a thin membrane, but a practical and theoretical, a utilitarian and an artistic separated by an equally thin membrane. And much as the function of Müller's volumes is dependent on the tension between that interior and exterior, so to is the function of his Volumes dependent on the tension between the practical and theoretical, between the utilitarian and the artistic.

And which means that for all that very convincing arguments can be made for a greater use of pneumatic architecture, for the construction of conurbations on the basis of pneumatic architecture, the process of developing plans for such buildings and communities enables, empowers, one to reconsider our built environments and our architecture, enables, empowers, one to question long practised conventions and standards. A rethinking that is necessary not just in context of contemporary architecture’s sustainability problem, the dangers inherent in contemporary architectural practice, but in context of the climatic and demographic challenges that are approaching, in context of the ever smaller expanses of space available, in context of developing technology, in context of a society that is becoming ever more transient, etc...

A rethinking enabled and empowered by the very different perspectives on what architecture and the built environment is arsing from pneumatic architecture and the very different relationships with not just buildings arising from pneumatic architecture but with space both exterior and also interior: how does one furnish a Volume, how does living in a Volume inform your relationship with furniture and furnishings, how does living in a Volume define the furniture, accessories, decoration et al you have?

And how does an architecture that employs air as construction material, that is as dependent on air as we all are, impact on our relationship with that air. We still can't see it, but could we begin to view it differently, pay more attention to it?

Or put another way: the buildings and spaces a Hans-Walter Müller proposes and promises have nothing to do with those we currently have, nothing to do with them either materially or immaterially, nothing to do with them either physically or conceptually, if we were to develop them where would that take not just buildings and spaces but the communities, society's and individuals who use them?

How can we develop architecture and urban planning in context of the realities and challenges of now and of an unknowable future?

The answers one develops may not be pneumatic, but much as Hans-Walter Müller's experiences of and experimentations with light, space, mime, magic, kinetic art et al influenced and informed his pneumatic architecture, so can his pneumatic architecture influence and inform our future architecture.

As can mime and magic.

A mime and magic we generally need a lot more of in contemporary global society.

Hans-Walter Müller isn't the only creative working in pneumatic architecture today, but as one of very few, potentially the only, to have continually worked with, on and in Volumes since the 1960s, to have developed his positions on pneumatic architecture since the 1960s, is one of the most important practitioners and theoreticians.

And thus an important, informative and instructive entry point to pneumatic architecture for all who more normally associate the term with bouncy castles.

Through its basis in uncommented photos, and the numerous strands of practical and theoretical discussion the canon of Hans-Walter Müller invites one to traverse, Monsieur Luftarchitektur is an introduction to the work of Hans-Walter Müller that demands a goodly degree of active participation from the visitor, both during and after your visit. Which is always welcome, the harder you work in an exhibition that greater benefit. Think of any museum as a gym for the mind, for the spirit, for your non-physical self.

Work that when undertaken not only allows you to become acquainted with a creative who has worked under the popular radar for some six centuries while developing a canon of physical and theoretical work that needs must be on the radar, but also allows you to begin the questioning of architecture and urban planning, of relationships with buildings and spaces, of why our built environment is the way it is, how it could look, what are the arguments for change, what are the arguments for continuation, that we all must make: for lest we forget, where an architect was one a man, it is now the community. We all needs must be involved in decisions on the built environment.

Which is also a reason why regularly imagining alternative architectures is so important. What if the inflated Volume was the standard in our urban spaces?

And is also a very nice context in which to view the permanent exhibition within Amberg's Luftmuseum, an interactive presentation that contains a lot more air than its physical dimensions allow, and which with its myriad artistic and utilitarian approaches to and reflections on associations between air and humans, is an admonishment to urgently consider the air that is all around us, but which we only rarely consider. Except when it becomes sacre or dirty. By which point, its too late. For us and for our architecture.

Monsieur Luftarchitektur – Hans-Walter Müller. Architekt, Ingenieur, Künstler; 1967 bis heute is scheduled to run at the Luftmuseum, Eichenforstgäßchen 12, 92224 Amberg until Sunday September 14th

Further information can be found at www.luftmuseum.de

1see Robert Stürzl, Hans-Walter Müller und das lebendige Haus, Spector Books, Leipzig, 2022 page 51

2Hans-Walter Müller, Pourquoi le gonflable?, Technique et architecture, Juin 1975, reprinted in a German translation in ibid