Verner Panton – Colouring a New World at Trapholt, Kolding

“Space and form are important elements in the creation of the [interior] environment”, opined the Danish architect, artist and designer Verner Panton in 1969, however, he continues, “colours are even more important”.

And no-one, even those with but the briefest familiarity with Verner Panton, can oversee the colour in Verner Panton’s work.

Yet important as colour and space and form were for Panton, “in the creation of the [interior] environment”, “l’homme reste l’élément central“, man remains the central element.1

With the exhibition Verner Panton – Colouring a New World, Trapholt, Kolding, undertake a search for the human in the colourful new world of Verner Panton.

From Light and Colour to Colouring a New World

One of our favourite Verner Panton stories, certainly in terms of colour, concerns the interior design Panton realised for the Basel apartment of the, then, Vitra CEO Rolf Fehlbaum, and which saw Panton set each room in one colour, and one colour alone – walls, floors, ceilings, furniture, textiles, everything, in the same colour. A green room, a red room, a black room, etc… Fehlbaum’s question if he could move an item from one room to another being greeted by Panton with a quizzical, why would you want to?2

An idea of the interior of Rolf Fehlbaum’s apartment can be approached, though, we suspect, not fully understood, in Verner Panton – Colouring a New World via a recreation of Panton’s 1998 Trapholt exhibition Light and Colour: eight narrow presentation spaces, each in a single colour, sandwiched between mirrored walls….. an unyielding sensory assault and a horizonless, infinite, rainbow that appears to be leading you into a psychedelic wormhole from which you know you can never return. Yet into which you go gladly.

Wow! is your initial response, as you stand, and stare, captivated, lost, trying hopelessly, helplessly, to find some point of reference on which to anchor yourself, to anchor your thoughts, to anchor your senses. Your second response is to grab your phone to capture the indescribable in photos…… which is when you notice the mix of light sources and colour tones plays havoc with your white balance, but once you’ve got that sorted, your biggest problem is where to start photographing. And then when to stop.

However, if you pause your photographic frenzy, and actually look at the furniture and lighting on show, you quickly realise it is an extremely low-key, unemotional, almost banal, presentation. There is, you tell yourself, no presentation in the presentation, none whatsoever, no attempt to actually present the furniture; rather, you continue, it’s furniture on pedestals and lights on the floor/ceiling without any accompanying texts or context, they just stand there as if forgotten in a storeroom, and you feel left entirely on your own, without the slightest of clues, in your to attempt to bring the disparate objects together into some sort of meaningful whole.

The dichotomy between the muted achromatic presentation and the screeching polychromatic scenography is just joyous, as in gloriously. Monumentally.

And also very satisfyingly encapsulates the manner in which the works of Verner Panton popularly exist; the popular focus on form and colour meaning the objects themselves are all too often neglected, and which tends to a situation in which much of Verner Panton becomes lost in distractions of form and colour.

You’re standing in an analogy. And a metaphor.

And which makes the discombobulating wormhole a both joyous and apposite location to begin viewing Colouring a New World.

And also the ideal location to end viewing Colouring a New World.

Living Tower (1968/69) in the recreation of the 1998 exhibition Light and Colour, as seen at Verner Panton – Colouring a New World, Trapholt, Kolding

Can questions answer questions?

In the 1980s Verner Panton presented, on several occasions3, a speech in which he begins by asking his audience if questions can answer questions, before, and without waiting for a response, launching into 10 minutes of questions on, for example, contemporary design, contemporary interiors, contemporary furniture, the contemporary furniture industry…….

A speech which in 1995 was published in German under the title Meine Design-Philosophie, My Design Philosophy4, a text reproduced in Danish and English on the walls of Trapholt; and questions around which Colouring a New World‘s narrative is structured.

Or at least part of its; for although very much one exhibition Colouring a New World is composed of two distinct components: the recreation of Light and Colour, and a curated exploration of Verner Panton, of Verner Panton’s oeuvre, of Verner Panton’s colourful world.

An exploration which opens with a chronological biographical tour through Panton’s career staged on the Trapholt mezzanine, and which takes you in five bijou presentations decade for decade from the 1950s to the 1990s.

A biographical tour undertaken in the company of objects from across Panton’s long and varied career, including, and amongst others, his 1950s Bachelor Chair for Fritz Hansen, his first commercially produced design and a work which deliciously re-imagines of Kaare Klint’s 1930s Safari Chair for a new generation; the 1978 Pill Chair, an all too rarely seen Panton design and which with its interchangeable upholstery elements is a reminder not only of Panton as a designer very much aware of the designer’s ecological responsibilities but also Panton as an experimenter; or the ever endearing and genial 1992 Vipp rocking chairs for PP Møbler which combine the Postmodernists reclaiming of the pure geometric form with the pared-down formal aesthetics of a Michael Thonet in objects with gallons of wit. In both senses

A biographical tour undertaken in the company of numerous examples of Panton’s spatial design projects, including, and amongst others, Panton’s scenography for the applied arts section of the 1959 Danish Trade Fair, and for which Panton fixed the furniture, upside down, on the ceiling, which wasn’t a thing in 1959; his interior design for the Spiegel HQ in Hamburg in which, and in a recurring theme of Panton’s work, each floor had its own colour scheme, its own hue appropriate to, psychologically supportive of, the work carried out on that floor; or his refurbishment of the Circus variety/theatre in Copenhagen, a project which is partly recreated in Colouring a New World, and while one can’t enjoy the full splendour of Panton’s interior, one can approach an understanding of its scale. And colour.

But for all a biographical tour undertaken in the company of Panton’s questions, in the company of Panton’s Design-Philosophie: “Is the interior designer afraid of what his colleagues would say if he created something unusual?”, Panton asks, “If an artist’s work does not meet with resistance, does that make them a bad artist?”; “Is interior design a science, an art, a function or a random happening?”; “A few years ago interior design objects were intended to have a short lifespan, today they once again have to last for years, might one possibly do things differently so that the things last, but can always be dressed differently, like ladies?”, the last two words being an unfortunate adjunct today, but which reminds us all that the text arose in a previous century.

And thus a biographical tour which through the unfamiliar context in which it places and surveys Panton’s oeuvre, helps initiate and encourage, demands, differentiated reflections on and approaches to Panton’s oeuvre, and for all helps shift your focus away from the objects and the projects and towards the whats, whys and wherefores of the objects and the projects.

Ring lamp (1969/70), Flower Pot lamps (1968) and Pill Chair (1978), as seen at Verner Panton – Colouring a New World, Trapholt, Kolding

Is well-being found through furniture?

For Colouring a New World‘s curator Sara Staunsager the key to Meine Design-Philosophie, the key to Panton’s design philosophy, a key to Verner Panton, is his “interpretation of the concepts of taste and well-being”, an argument she very diligently and convincingly expands upon in the (forthcoming) catalogue, and to which we refer you dear reader.5

As an exhibition Colouring a New World primarily approaches Panton’s “interpretation of the concepts of taste and well-being” through an elucidating of the primacy for Panton of the interior environment as a holistic, responsive, active space rather than as a fixed, static, defined space; or as Panton opined in context of the 1969 exhibition Qu’est ce que le design? at the Centre de Création Industrielle, Paris, “in my own work, I focus particularly on the overall result. Relationships with the environment have an importance which goes far beyond those concerning only a chair or any other object: a room, a colour, furniture, textiles, lighting must be considered all together.”6

And not just the physical features “must be considered all together”, as Colouring a New World helps one appreciate Panton’s interior is dimensionless and is to be employed and enjoyed and experienced as such, helps elucidate that Verner Panton didn’t see a space as only a physical environment, important as that was, but also as an emotional, tactile, sensuous environment; thus when he asks, “Is a feeling of well-being primarily the discerning of pleasant proportions, good colour and material combinations, comfortable lighting by day and pleasing evening lighting?” it is very much in conjunction and connection with, inseparable from, his question, “Isn’t well-being good music, an agreeable aroma, good food and drink, pleasant company, good entertainment?” And/or, “Isn’t for most people sex the best form of well-being?”

“Is well-being an intellectual or an emotional experience?”

¿Is the question that simple?

¿Is sex that simple?

Pantonaef building block animals (1975), and a view into the Panton family home, as seen at Verner Panton – Colouring a New World, Trapholt, Kolding

Could one develop a theory on well-being?

Considerations of the importance of the emotional, tactile, sensuous in Verner Panton’s oeuvre that allow Colouring a New World to reinforce Panton as a Functionalist, as a post-War Functionalist with an expanded, extended, definition of Functionalism that goes beyond the technical functionality of the inter-War functionalists and understands the emotional functionality, understands the necessity of the emotional functionality, understands that our objects of daily use, the environments we create for ourselves, are not just there to serve us mechanically, aren’t a mute aid to be scientifically optimised, but are entities with which we interact, with which we engage, which impact upon us, which inform and influence us, “In the forest, on the beach, in the sun, when it snows, you generally feel good. But isn’t it more difficult in a room where everything is shaped by human hands?”

And a Pantonian understanding of the necessity of considering the interior in its dimensionlessness Trapholt’s visitors are invited to explore for themselves: “Why are sounds reproduced in an apartment always music? Are the sounds of chickens – waves – the wind and many other things not equally beautiful?” Panton asks in Meine Design-Philosophie: and in Colouring a New World you can relax on a Pantonova bench while listening to clucking chickens, and/or listen to gently breaking waves from the comfort of a Cloverleaf sofa, and/or lounge in a Flying Chair while the wind whooshes around you. And, invariably, while you take a selfie.

For there are a lot of selfie moments in Colouring a New World, even if the nature of the narrative and its countenance against the popular objectification and easy pigeon-holing of Panton’s work, against its reduction to form and colour, does cause you to reflect on whether you should take selfies. But you still do. Obviously

Something perhaps best illustrated by the selfies you’ll take inside the recreation of Panton’s Fantasy Landscape, part of his 1970 Visiona 2 exhibition in Cologne, and that “garish Alice in Wonderland hell cave” which as an immersive, dimensionless, 360 degree environment, is not only, and as noted in our post on the unrealised, ¿unmade?, Panton Bed, a continuation, an escalation, of ideas on immersive environments Panton had begun a decade earlier, but also represents both one of the most fulsome expressions of Panton’s understandings of an environment, and embodies that challenge to us all to question our interior environments which is inherent in Panton’s work, or as he opined in 1970 of Visiona 2, “one can describe such experiments as utopic, but they help us to expand our experience. And that is what it is all about”.7

That, and an Instagram post that can’t but be popular. But will fail to capture the essential essence of the environment.

Is “good taste” a burden?

In addition to posing direct questions of taste and well-being Meine Design-Philosophie poses questions across a wide scope of subjects which, although varied and disparate, are all related to Panton’s reflections on taste and well-being, his questioning of taste and well-being, subjects such as, and amongst many others, the mediation of design and interiors, “There are interiors magazines who publish new trend colours every year. Is that really necessary?”, “Why do most interiors look essentially the same?”, “Is too little written on the subject of ‘living differently’?”; thoughts on colour, including themes he discusses at more length in his 1997 book Lidt om Farver/Notes on Colour, such as “Can colours create well-being?” or “Is it laziness or ignorance that means people want everything in white or beige?”; and also thoughts on the furniture industry, “Do the furniture and furnishings stores show new approaches and experiments?”, “Are you giving creative advice to customers or just wanting to make a quick deal?”, “Why so much new furniture all the time?”, “Who decides, [what furniture is available] the customer, the man on the street, the furniture dealer, the designer or the manufacturer?”

And when he asks “Werden wir in 100 Jahren so wohnen wie heute?”, “Will we live the way we do today in 100 years?”, one gets the very real sense he fears we will. And 40 years since he first delivered the speech we largely are, we are still largely living in 2D, flat, static, spaces.

Meine Design-Philosophie is Panton’s argument that alternatives are possible, are desirable, are necessary, and Colouring a New World an illustration not only of that position but of how that understanding inhabits and infiltrates Panton’s works; and in doing so helps one appreciate that much as Panton’s Design-Philosophie is, or certainly as published in 1995 is, a series of questions, so his works, his projects and objects, are rarely answers, occasionally they are, but they are primarily questions. And certainly only rarely definitives: one needn’t necessarily consume that which Panton created, nor design an interior as Panton would, rather Panton’s works should be approached as propositions, admonishments to discussion and debate.

Something neatly illustrated by Panton’s aforementioned interior design for Rolf Fehlbaum: while Panton was clearly convinced, Fehlbaum less so, and thus having lived with Panton’s concept, and thereby deciding against it, Fehlbaum redecorated.

Which we don’t imagine would have offended Panton; on the one hand as Meine Design-Philosophie elucidates, for Panton experimentation was important, central, in the development of new interior environments, yet something for him far too infrequently undertaken, promoted, encouraged, risked. And on the other because Panton understood the complexity and variety of the human species: that whereas for the inter-War Functionalists, and simplifying dangerously, the way forward was a standardised one-size fits all approach, as Panton opined in 1969 in context of Qu’est ce que le design?, “fortunately people differ greatly from one another, and even the best-planned environment must take these differences into account in order to meet its ends. Only in this way can an environment become an integral part of an expression of life.”8

“Fortunately” is for us the key word in those sentences.9 And, yes, it does sound like a metaphor.

And a comparison of Panton with the Inter-War Functionalists and their “interpretation of the concepts of taste and well-being” we’ve now drawn for a second time in this post; and that one feels not by chance, not for lack of other thoughts and possible comparisons.

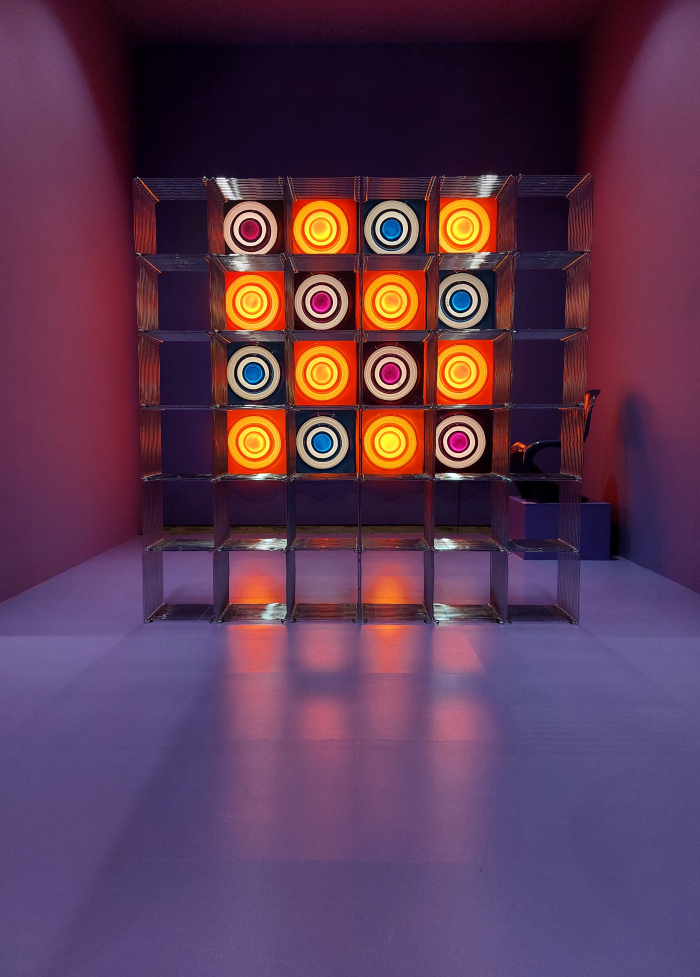

Panton’s Ring Lamp (1969/70) in cooperation with a Wire shelving unit (1971), as seen at Verner Panton – Colouring a New World, Trapholt, Kolding

Is design today art or styling?

For all that Panton’s objects may appear aeons removed physically and materially for that which came before them, as Colouring a New World helps one appreciate, Panton’s objects (largely) continue the reduced rationality that, arguably, began in the days of Art Nouveau and and whose intensification runs through developments and evolutions in design, and they also largely continue the focus, as with certainly the International Modernists, on new materials as the only logical, meaningful, path forward; however, for all that Panton’s objects are essentially continuations of established understandings, Panton, we’ll argue, shifts the value.

Throughout (hi)story, and we’re still simplifying dangerously, regardless of where the various and varied craftsfolk and designers responsible for the objects with which we surround ourselves, placed the value, be that in, for example, decoration, practical usability, material purity, that value was invariably on and off the object as an entity itself.

Verner Panton, we’ll argue, and having viewed Colouring a New World feel emboldened to do so, questioned that. Verner Panton defined the value of an object in context of its function within a space, as a component of a whole, not as something inherent within an object regardless of the context in which it exists.

Not always, as with everything in life not only are there always exceptions, but nothing is that simple. The only things in human existence that are truly black and white are old-skool Ska boys and girls.

Nor was Verner Panton alone in such, for all his myriad Italian contemporaries of various hues were pursuing and proffering similar ideas.

We’re not claiming anything uniquely or consistently Pantonian.

But, for us, understanding Verner Panton involves understanding him as both a continuation of and break with all that came before, not “break” as in flat out rejection, kick it down and start again; but “break” as in, your methods, your ideas, your approaches, your definitions have brought us thus far, but are no longer applicable for our society, society is evolving and we need to reposition, reimagine, evolve, our “relationships with the environment”. And which, yes, is also comparable with the Art Nouveauists or the International Modernists, they were also about repositioning and reimagining. And also about placing the human at the centre of an environment, in many regards for the Art Nouveauists or the International Modernists l’homme reste l’élément central.

But their l’homme was different, their understanding of l’homme was different, their definition of l’homme was different, and that (primarily) because the society in which their l’homme existed was different.

For Verner Panton keeping l’homme at the centre of an interior environment wasn’t, as it had been for the Art Nouveauists or the International Modernists, a question of new objects, necessary as they may have been, but about questioning the intangibles in an interior environment, questioning our relationships with the intangibles in an interior environment, questioning our definitions of the intangibles in an interior environment, of understanding humans as components of an interior environment rather than users of an interior environment, of understanding the complex relationships between objects and an interior environment, between humans and an interior environment, between humans and objects.

And that redefining of the value of objects, and that redefining of space was new. Again, not uniquely Pantonian, but very much at the core of the Pantonian approach.

And which thereby tends to an appreciation that the relevance of Verner Panton today is less his objects and projects, but what those objects and projects can teach us about the very real necessity to continually question not only if those interior environments we create for ourselves are appropriate, fit for purpose, but if we are starting from a meaningful definition of interior environment, if our definition of well-being is meaningful, fit for purpose, for if it is not, neither will our interior environment; that the relevance of Verner Panton today is that which you can’t capture in your Fantasy Landscape selfie. Not least on account of the distractions of form and colour.

Thus allowing you, after viewing the rest of Colouring a New World to return to Light and Colour in possession of the tools you need to better approach the discombobulating wormhole, to see the presentation in the presentation you missed, oversaw, and to deconstruct the dichotomy between presentation and scenography.

Wow! is still your response when you return.

And while the forms and colours are still here, and are still captivating, they are no longer distracting, the rest of Colouring a New World having, as it were, helped you correct your metaphoric white balance.

Isn’t that what it’s ultimately all about – about habitation, living?

Verner Panton ends the speech which became Meine Design-Philosophie, his 10 minutes of incessant questioning, with the rhetorically very satisfying “Es dürften keine Fragen gestellt werden”, “Questions are not allowed”. Leave them laughing, always the best idea.

The structure of Colouring a New World and for all its very pleasing mix of popularly known and much less so objects and projects, backed up and supported by photographs, sketches, models and succinct, accessible, Danish/English texts, and ample selfie moments, should leave you happy, if not necessarily laughing.

And will definitely leave you with more questions than when you came. Which is, inarguably, how any good exhibition should leave them, hungry for more.

Questions not only on your opinions of Verner Panton’s Design-Philosophie, nor only on your own “interpretation of the concepts of taste and well-being”, but also on your understandings of the “creation of the [interior] environment”, of the priorities in the “creation of the [interior] environment”.

Questions which in the wake of Corona and the increased time many of us will have spent in our own interior environments, also spent working in our own domestic interior environments, will arguably be more focussed than they otherwise might have been.

Questions which are becoming increasingly shaped and informed, and acute, in our contemporary networked homes, through the ever more pervasive “smart” technology with which we share our homes, and which is/are directly influencing and altering “relationships with the [home] environment”, are becoming components of our dimensionless interior environments, factors in definitions of well-being. And also in and of our relationships with those with whom we share our domestic environments. And as such need to be critically considered, actively questioned.

And also questions on those myriad subjects that a Verner Panton can guide you into, including, and amongst many others, objectification, with its associated reflections on the social media Verner Panton didn’t have, but you imagine he’d be all over today, he was a shrewd communicator; or ergonomics, should furniture move with you, for you or force you to move; or contemporary understandings of design in and from Denmark, with associated reflections on the cursed, foul, plague of H****; or Verner Panton’s relationship with/to the (hi)story of design in and from Denmark, yes, we still owe you an answer to the question “er det dansk?, is it Danish design?” in context of Arne Jacobsen, and we haven’t forgotten, we will return to it, but the same question applies to Verner Panton, “er det dansk?, is it Danish design?”

A questioning upon questioning that thereby enables Colouring a New World to not only allow you to reflect on design, for all interior and furniture design, in wider contexts, nor only to move a little closer to the oft obscured Verner Panton in the Verner Panton oeuvre, but for all to hypothesise that, in the new world Verner Panton foresaw, alongside the colour supplied by industry and nature, an important component, arguably the most important component, was the colours of life, the colours of humanity in all its tactility, emotion, variety, playfulness and sensuality.

Verner Panton – Colouring a New World is scheduled to run at Trapholt, Æblehaven 23, 6000 Kolding until Sunday August 14th.

Full details can be found at https://trapholt.dk

And as ever in these times, if you are planning visiting any exhibition please familiarise yourself in advance with the current ticketing, entry, safety, hygiene, cloakroom, etc rules and systems. And during your visit please stay safe, stay responsible, and above all, stay curious……

- A rainbow wormhole and numerous Panton lights, including Dodecahedron 1998/2021), as seen at Verner Panton – Colouring a New World, Trapholt, Kolding

- System 1-2-3 chairs (1973/74) and Onion lamp (1977), as seen at Verner Panton – Colouring a New World, Trapholt, Kolding

- A herd of Phantom’s (1997) under a VP Globe (1969/70), as seen at Verner Panton – Colouring a New World, Trapholt, Kolding

- A selection of Panton moulded pylwood seating including, the Pantonic and Pantoflex families, and the Tatami low seater, as seen at Verner Panton – Colouring a New World, Trapholt, Kolding

- Pantonova (1971) in front of a carpet featuring the design Welle (and all surrounded by clucking chickens….), as seen at Verner Panton – Colouring a New World, Trapholt, Kolding

- Panton Chair and development sketches, as seen at Verner Panton – Colouring a New World, Trapholt, Kolding

- The 1950s, incluidng reference to Panton’s scenography for the 1959 Danish Trade Fair, as seen at Verner Panton – Colouring a New World, Trapholt, Kolding

- Ergonomics à la Verner Panton, Self-Stabilising Stool (1981) & Spiral Chair (1994), as seen at Verner Panton – Colouring a New World, Trapholt, Kolding

- A partial recreation of Panton’s interior of the Circus Building Copenhagen, as seen at Verner Panton – Colouring a New World, Trapholt, Kolding

- Two glass chairs (1998) and the sculptures mirror, as seen at Verner Panton – Colouring a New World, Trapholt, Kolding

- The Anatomical Designs print series (1968) and Spiral lamp (1969/70), as seen at Verner Panton – Colouring a New World, Trapholt, Kolding

- Panton chairs and Geometri fabric by way of illustarting the effcets of different colours, as seen at Verner Panton – Colouring a New World, Trapholt, Kolding

- A selection of Panton works including the Pantheon sofa (1985) and various VP Europa lamps, as seen at Verner Panton – Colouring a New World, Trapholt, Kolding

- Not all colourful, but all contributes to the colour, Panton’s Plexiglass Chair, as seen at Verner Panton – Colouring a New World, Trapholt, Kolding

- Panton chairs and a rainbow wormhole, as seen at Verner Panton – Colouring a New World, Trapholt, Kolding

1. Verner Panton in Joe C. Colombo, Charles Eames, Fritz Eichler, Verner Panton, Roger Tallon: Qu’est ce que le design?, Centre de Création Industrielle, Paris, 1969 … in 1969 language was still very male centred, let’s assume Panton meant homme in terms of people/humans/us all.

2. We have heard the story most often orally, however Rolf Fehlbaum makes brief reference to it in Alexander von Vegesack & Mathias Remmele [Eds.], Verner Panton: the collected works, Vitra Design Museum, 2000. There may be other written sources we are unaware of.

3. The exhibition catalogue lists all the (known) occasions on which Panton held the speech, [Catalogue delayed on account of global supply chain issues and due in November 2021, May 2022, we’ll add details once it is published]

4.Verner Panton: Meine Design-Philosophie,BÜROszene, Vol 47, Nrs. 1–2, 1995, all quotes unless otherwise stated our translations of the original German.

5. see exhibition catalogue [Catalogue delayed on account of global supply chain issues and due in November 2021, May 2022, we’ll add details once it is published, Trapholt very kindly supplied us with a preview of Sara Staunsager’s essay, for which we are grateful and thankful.]

6. Verner Panton in Joe C. Colombo, Charles Eames, Fritz Eichler, Verner Panton, Roger Tallon: Qu’est ce que le design?, Centre de Création Industrielle, Paris, 1969

7. Stern Nr. 8 15th February 1970

8. Verner Panton in Joe C. Colombo, Charles Eames, Fritz Eichler, Verner Panton, Roger Tallon: Qu’est ce que le design?, Centre de Création Industrielle, Paris, 1969

9. The word used is Heureusement which awakens a myriad positive associations…

Tagged with: Colouring a New World, Design. Colour. Theory., Kolding, Trapholt Museum, Verner Panton, Verner Panton. Colouring a New World