smow Blog Design Calendar: October 24th 1969 – Opening Qu’est-ce que le design? @ Musée des Arts Décoratifs Paris

Qu’est-ce que le design?

What is design?

A question as old as the word itself, arguably older. But one with an answer?

In an attempt to approach one the Musée des Arts Décoratifs Paris asked Charles Eames, Verner Panton, Roger Tallon, Joe Colombo and Fritz Eichler, Qu’est-ce que le design?……

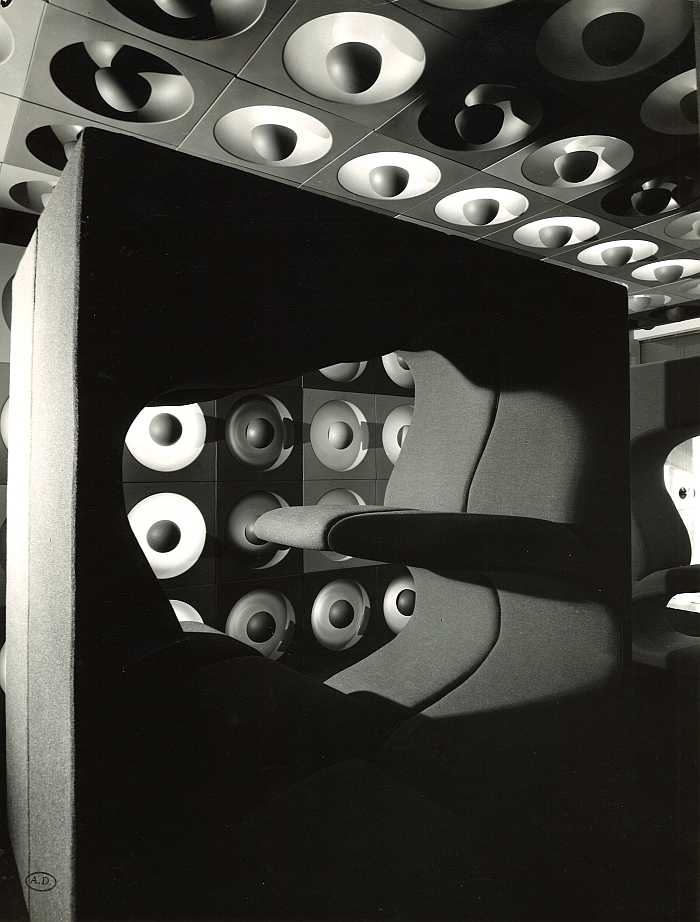

A view of Verner Panton’s installation at Qu’est-ce que le design Musée des Arts Décoratifs Paris 1969 (Photo Pierre Jahan © and courtesy Musée des Arts Décoratifs Paris)

Organised in context of the establishment of the Centre de création industrielle, CCI, and opened to the public on October 24th 1969 in the Musée des Arts Décoratifs Paris, Qu’est-ce que le design? featured not only five of the leading international designers of the period but five designers who, on paper, represented five very different understandings of design: Charles Eames, one of the leading proponents of that post-War American interpretation of functionalism; the young Italian radical Joe Colombo with his utopian visions of our domestic spaces and understandings of design as much as a branch of linguistics as 3D forming; Roger Tallon, the Grand Doyen of French design, and for all of technical design for industry; Fritz Eichler, the first Design Director at Braun, a man very much associated with technical design for consumers, and the sober reduction of Germanic gute Form; and Verner Panton with his pop tendencies, holistic compositions and understanding of the role, the near primacy, of colour in design.

Conceived as a new institution within the long established Union centrale des Arts décoratifs the CCI was tasked with encouraging and promoting design, with, if you will, establishing a clear distinction between the decorative/applied arts and design, and thus its inaugural exhibition can be understood very much as an attempt to draw a first line in the sand. To this end each of the five designers presented works from their portfolio which they felt represented them and their understanding of design, objects backed up by a short essay, Fritz Eichler, for example, explaining Braun & design, while Joe Colombo elucidated on his reflections on “a different architecture for a different way of living”, noting “research on a new methodology of architectural design can only have one starting point: an ecological study of the man of today and especially the microcosm in which he lives.”1 Which he subsequently did.

In addition each of the five answered 26 questions set by curator Henri Van Lier, or more accurately, four of the five did, Verner Panton being represented by his essay alone. Why Verner Panton didn’t answer the questions is lost in the mists of time, and is a regrettable absence, because a comparison of the answers of the other four helps us not only understand the positions and approaches of the individuals, but also, and with the benefit of the intervening neigh on fifty years accumulated design history and evolution, helps illuminate just how understandings of design have evolved, how answers to the question Qu’est-ce que le design? have evolved. And also how they haven’t.

And in such a discussion a Verner Panton’s voice would, we feel, have been as interesting as it would have been important.

As it is we have the opinions of Joe Colombo, Roger Tallon, Fritz Eichler and Charles Eames.

Roger Tallon’s installation at Qu’est-ce que le design Musée des Arts Décoratifs Paris 1969 (Photo Pierre Jahan © and courtesy Musée des Arts Décoratifs Paris)

While the responses of each of the four to each of the 26 questions individually are of interest in their own rights, of particular interest is a comparison of the answers to those questions which still have a relevance today.

The fact a question posed to a designer in 1969 remains relevant in 2018 being one of the more obvious indicators as to how little we have progressed since the year of the first moon landing.

Question 19 for example concerned that most contemporary of design considerations, obsolescence “Is design ephemeral? Should it tend to the ephemeral? Must it have a permanency?” asked Henri Van Lier. A question very much of its time. Previously the question didn’t exist, things were made to last forever, but then, particularly inter and immediate post-war, an increasing fluidity in society meant objects weren’t expected to last forever, weren’t meant to become heirlooms, were meant to become obsolete and replaced, a shift supported by the development of new synthetic materials, before, and as noted in context of the exhibition Victor Papanek: The Politics of Design at The Vitra Design Museum, in the course of the 1960s such temporal relationships began to be viewed more critically. Or perhaps better put, slowly began to be viewed more critically, as Qu’est-ce que le design? helps illustrate.

Whereas Fritz Eichler was unequivocal that “a design deliberately conceived with a short lifespan can only be bad”, Joe Colombo saw obsolescence as an inherent part of the design, opining, “from a practical point of view, a design product depends on the obsolescence that determines its wear & tear, its consumption and therefore its design”, a circular argument which isn’t pro-obsolescence rather makes it product specific, similarly Roger Tallon differentiated between objects conceived to be thrown away and those conceived for long term use, and therefore, as with Colombo, tacitly accepting obsolescence as inherent and admissible concept in design. Which for many it remains today, when in new guises. Charles Eames, in that quietly poetic manner of his, very neatly quantified what that, invariably, means, “some needs are ephemeral. Most products are. Those needs and products that have a universal quality will tend to permanence.”

Then there is Question 14 which asked, “Is design an element of a commercial policy? Good product = brand image. Good packaging = best seller?” We all know that today a great many companies use “design” as a marketing tool, or perhaps better put companies use associations with design, a smack of design, a deceit of design, to gain a market advantage, and/or hire a big name designer for a project, calculating that the name will lead to an automatic increase in publicity and thereby sales. The contemporary furniture industry being a particularly good/abhorrent, example. But such isn’t new, wasn’t new in 1969, and certainly wasn’t new to the four/five questioned, all having shown themselves proficient in terms of marketing and promotion. And all acknowledged that “design” plays an important marketing role, while underscoring the fundamental difference between the commercial value of real design and that which marketeers present as design, “there is neither a good nor bad form, nor even speculative forms that can substitute for poor technical and functional quality and lead to commercial success”, opined Fritz Eichler, and therefore underscoring that what you see isn’t always what you get. Similarly, if much more impassioned, Joe Colombo referred to his answer to Question 12 “Is design part of an industrial policy?” where he railed against the deliberate blurring of a marketing image with an object of design, a passion neatly encapsulated for us by the sentence, “the beautiful bright and colourful product, adorned with pseudo-cultural layers and “revival” mannerisms, and whose formal aspect more or less recalls the pure lines imposed by the laws of functionalism of the Bauhaus era and rational architecture, enchants the consumer who has already suffered through the action of the “media” and the objectification of design, a brainwashing.”

Curiously, or perhaps not, Charles Eames was almost silent on the issue, also referring to his answer to Question 12 and his view that, “Certainly: as much as any other aspect, obvious or subtle, of the quality of a product. It seems that anything can become part of a policy” Which does have light overtones of, quoi que.

Where Eames was however unequivocal was in his answer to Question 26.

Henri Van Lier: “What is the future of design?”

Charles Eames:

Joe Colombo and his Universale chair for Kartell. Not a Qu’est-ce que le design? exhibition photo, but both featured….

Beyond such, and similar considerations on, for example the relationship of form to function, relationships with engineers or if design is a collective or individual process, one finds questions clearly relating to the exhibition’s intention of differentiating between design and other creative pursuits, Question 18, for example, asking about designs relationship to fashion, where thankfully all are of the opinion that the two are fundamentally different, if capable of influencing one another.

While in a similar vein, and producing a similar degree of unity, Question 20 asked “How do you define yourself in relation to a decorator? An interior designer? A stylist?” None did. Were all most passionately adamant that they weren’t, perhaps most so Roger Tallon, “designers do not belong to a circumscribed and homogeneous professional category (despite the relentlessness shown by some of them to promote a protective “order” against the other “orders”). They are the result of professional transformations that inexorably benefit all creative activities, and which are conditioned by the technical and economic evolution of our society. The decorator, the architect, the draftsman, are the last survivors of activities born under the Renaissance and then maintained by the “monopole officiel” of the system of “Fine Arts” (training and diplomas – production and orders) charged with perpetuating the values of the dominant culture.”

We could go on, and believe us we want to, believe that despite its age, or perhaps better put, exactly on account of its age the answers contained in Qu’est-ce que le design? allow for some very interesting considerations and reflections on contemporary design, and for all underscore that there is no one single answer to the question.

The beauty of design, the joy of design, the relevance of design is that each and every practitioner has their own understanding of it, it’s why we can speak with confidence of design as a cultural discipline, it isn’t one with definable borders or set rules, but a response to given parameters in a given time and space. What distinguishes a “good” designer from a “less good” designer is their definition of design, the better designers possessing for all a better grounded definition of design, one that is clear, considered, defensible and is that which enables them to make objects that you can appreciate without actually liking. Whomever has only a muddled definition of design can only produced muddled works. Then there is that most dangerous of constitutions, those whose opinion is nothing but generic buzzwords, meaningless idioms, tired clichés and emotion laden semiotics. Such can only result in uninteresting generic nonsense of the lowest grade.

Ultimately it comes back to a question of honesty, that you have to believe in your beliefs in order to transform them into something tangible. Which sounds like the start of a parable. So we’ll stop.

And in any case much as we’d like to continue, much as we’d encourage you all to seek out a copy of the catalogue yourselves, ultimately, when all is said and done, Questions 2 to 26 are just deeper delvings into the answer implied in Question 1: Votre définition du design? – Your definition of design?

Charles Eames

A method of organising components to arrive at the best solution for a particular problem.

Joe Colombo

Design occupies an important place as it creates the instruments and arranges the frame essential for human life. It is a totality embracing architecture, town planning, production, means of communication … I would like to talk about “industrial design” or global production of the products and structures surrounding man in his immediate space, that is to say all that constitutes the microcosm in which he lives and moves. It is a problem for man – he lives – in space – he moves – he uses products, transforms them and consumes them. Man is in this case the extrapolated identity of the community that constitutes humanity. This analysis of the problem therefore starts from the centre moving outward, contrary to what is normally done, and which consists leaving the community to face urbanism immediately and to reach man only in the last analysis. I think that by solving small immediate problems first, it will then be easier to pose and face ever greater problems. Design is therefore reality, life, indispensable. Industrial Design is not a style; it is functional and rational. It is the total resolution of the internal problem of a product conceived in the most objective manner, with regard to the use for which it is intended. A product of design must have a meaning stratified into two essential values: the signified and the signifier, the former being derived from and a direct function of the second: the form is born exclusively of the content.

Fritz Eichler

Design is a complex ensemble, which is not limited to the design of an aesthetic exterior form, this is only the visible expression of a collective creation. Design is an integral part of our evolution. It is neither good nor bad in itself (although there is actually more good than bad design). It is impossible to make a uniform judgement, since it must take into account the diversity of conditions and objectives that determine design. Thus, design in the field of wall coverings and porcelain is other than that specific to highly technical and functional devices such as computers or machine tools. It is not enough to judge design on the formal aspect alone. It is necessary to take into account the objectives and conditions that decided the form. The more complex these conditions are, the more favourable the judgement must be, since the designer collaborating with technicians must create a formal, aesthetic, coherent and natural (conforming) creation.

Roger Tallon

That of the ICSID2, supplemented by this remark: design is not characterised by a specific creative activity but by the behaviour of the designer in the exercise of this activity – design is a conduct that refuses the unconsidered, the hazardous or inspired solution – it is “research of the information and the method for the remedy of the problem”

Verner Panton [abridged from his essay]

Through some kind of “artistic” mystery, design has unfortunately become a buzzword, diverted from its true meaning. Too many people consider that the designer is a man who adds a decorative touch to everyday objects, or denatures familiar shapes until they become new and elegant. The designer’s work is more than that, and much more important for society.

Three essential conditions must be met for this work to be done, and to testify by its positive result of the importance of the designer’s role in modern society: first, the designer must coordinate everything that is engaged in the production process. He must determine with the producers a common objective, and be prepared to integrate to their system of work his plan of production and its results. … The designer must also coordinate this process from the point of view of the consumer. He does not have to create immortal works of art, but objects that can be used in many ways by many people in particular circumstances. … Thirdly, the designer must give these strictly objective foundations a stimulus for the contemporary environment through the treatment of materials and his own work of forms and colours. This aspect, which is also more subjective, also responds to functional requirements. There must be a clear and deliberate cohesion between the practical and aesthetic factors.

1. And all quotes, from Joe C. Colombo, Charles Eames, Fritz Eichler, Verner Panton, Roger Tallon: Qu’est ce que le design?, Centre de Création Industrielle, Paris, 1969

2. International Council of Societies of Industrial Design The definition as it was in 1969 can be found at http://wdo.org/about/definition/industriael-design-definition-history/

Tagged with: Charles Eames, Design Calendar, Fritz Eichler, Joe Colombo, Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris, Qu'est-ce que le design?, Roger Tallon, Verner Panton, What is design?