Munich Creative Business Week 2018 Compact: Futuro 50|50. Die Welt 2068 @ the Pinakothek der Moderne

In front of the Pinakothek der Moderne in Munich stands a Futuro House by Finnish architect Matti Suuronen, a work realised in 1968 as his response to considerations on questions concerning our future society.

And an object which resembles a flying saucer. And arguably does so more now than it did then. Then it was a bright new future enabled by contemporary technology: now it is a piece of late 1960s science fiction.

Inspired by the Futuro House 28 students from the Industrial Design and Architecture Master’s degree programs at the Technische Universität München undertook their own considerations on questions concerning our future society.

The results of their deliberations are presented in the exhibition 50|50. Die Welt 2068.

If 2018 is fifty years after 1968, and 1968 is fifty years after 1918 then one is presented with an inalienable impression of how much can happen in fifty years: following the (hi)story of human civilisation from the war, nationalism and struggles for race and gender equality of 1918, on to the war, nationalism and struggles for race and gender equality of 1968, and, progressing ever further, right up to 2018 with its war, nationalism and struggles for race and gender equality, one understands just how irrevocably society evolves in conjunction with advancing science, technology and engineering. And thus how irrevocably human society will have further evolved by 2068.

But in which directions? What will be the pressing themes? What awaits us in 2068, and for all, how can/should we best respond to that which awaits us?

Exploring the year 2068 in context of education, digitalisation, health, climate, humanity, mobility and environment, 50|50 presents the visitor with a series of solutions, solutions which are as utopian as they are dystopian, solutions which as much as being proposals are also challenges to visitors to consider their own position, and whereas the number of variables to consider on the way to 2068 makes any form of definite vision impossible, that shouldn’t stop us all considering what for us are the desirables and undesirables in future society.

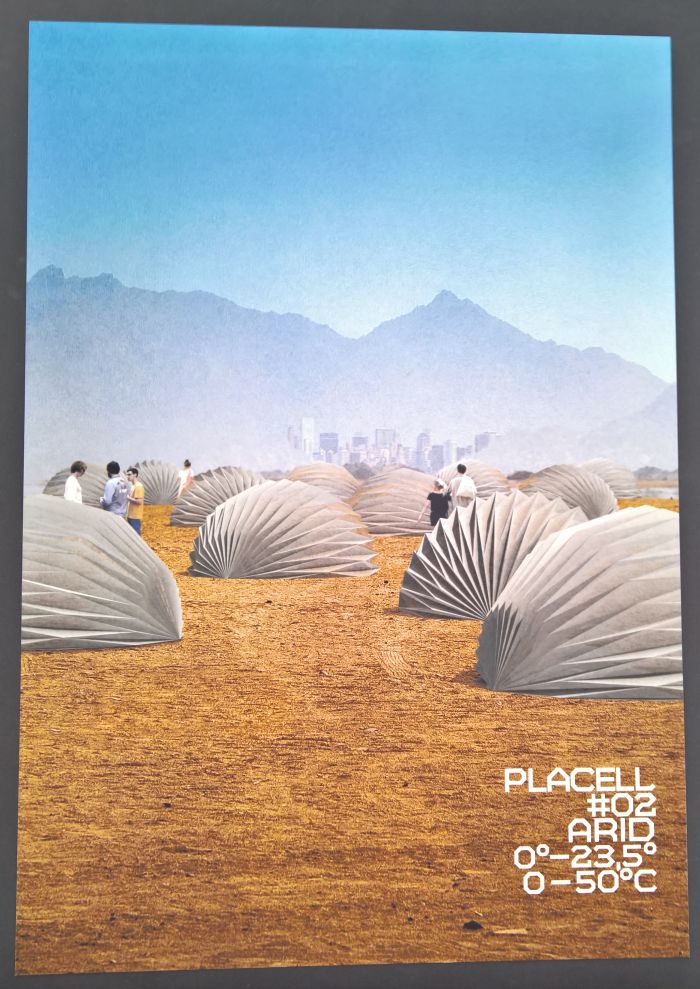

Our imagination was particularly caught by the environment section with the proposal for the creation of new islands to compensate for that land lost to rising seas, even if we hope that by 2068 plastic waste simply isn’t available in the quantities envisaged in the project and that other materials are in use; the health section with its considerations on the psychological effects of increasing technology neatly highlighted that smart as we like to think we are, we’re not, and we simply cannot predict the consequence of our actions; while the climate section with its Placell synthetic tents to protect us from the extremes of the future weather just plain terrified us.

Then there was the mobility section. Inevitably with its autonomous vehicles. And a section we wanted to take a moment to consider in a little more detail.

Urban Mobility 2068

As regular readers will be very aware, we don’t really understand the necessity of autonomous vehicles. Get very confused by the way they are generally accepted as logical. The section in 50|50 exploring future mobility served to reinforce our confusion.

Proposing a future urban transport system based on collective, artificial intelligence controlled, autonomous vehicles, the students listed five advantages of their proposal: no more traffic jams, no more accidents, no more changing bus/train en route, one vehicle for all purposes, transformation of parking houses to greenhouses. Arguments which to paraphrase the 19th century geologist Charles Lyell are “too obvious not to meet with general reception”1

Yet much as Lyell used “obvious” in context of over-simplified, easy and failing to properly consider other, wider, aspects, so do we.

A key aspect for us in considerations on autonomous vehicles is that they support and reinforce exactly the same level of egocentric handling which currently makes cars such an urban plague: everyone wants to travel by themselves when it suits them. Which leads directly to many of the problems apparently so elegantly solved by autonomous vehicles. Yet should a central feature of any logical, sustainable future transport solution not involve resolving our egos, of accepting that we live together, and can also travel together. That it is OK to take the tram/bus/train/underground. It’s OK change bus en route, or change from bus to train. It’s OK to wait a little, set off a little earlier or later. To walk a couple of streets. And for those who want full independence, the bicycle has been providing democratic, cost-effective, direct, door-to-door, individual transport in urban and rural areas for two centuries. And arguably could do for another two. Or three. Or four. Etc.

Arguably a focus on promoting increased use of bikes and public transport, rather than encouraging our selfish habits, could not only also allow for the transformation of parking houses to greenhouses, reduce pollution and reduce urban traffic jams and therefore improving urban spaces, but also make us all a little more sociable and fitter*

And if we accept that autonomous vehicles are inevitable, who is going to pay for such a public system? Local authorities are, as a general rule, reluctant to invest in public transport. America being a particularly good example, rural America being an even better example, while even in Europe where the situation is much better, most of us are only too aware that our local public transport networks could be better funded.

Yet we’re expecting these self same local authorities to invest in establishing and maintaining fleets of autonomous vehicles. Why? Why would they do that? What is so fundamentally different between maintaining a bus/tram/underground network and establishing and maintaining an autonomous vehicle network that makes investing in the later so appealing?** Have you asked your local authority how they plan to implement such systems?

And if the local authorities can’t or won’t pay?

As an alternative there is always those, oh what do you call them……. you know….. those, hhhmmmmmm… it’s on the tip of our tongues, oohhhhh …… Californian tech conglomerates! You know those people who know everything about you, who will know even more about you after they have chauffeured you through the city a few times, and who can also ensure your journey is accompanied by personalised advertising based on your social media, fitness watch, smart speaker and movement profiles.

Is that the future you want?

And if not, what do you want?

We’re not fundamentally against technology, we’re not Luddite mobility reactionaries who curse the day Stephenson’s Rocket won the Rainhill Trials, honestly we’re not, the question is the meaningful application of technology. Just because something is possible doesn’t mean is either desirable or the best solution. A lot of the arguments, for example, about autonomous vehicles being safer is largely about systems where the vehicle monitors its environment and responds to dangers, systems which can be employed to varying degrees in “driver” cars, don’t need the full autonomous networked experience, while, and to return to the human ego, most accidents are caused by driving too fast, too aggressively or simply not concentrating: slow down, pay attention, take your time and you’ll crash less. The Munich students indicate their pods will travel at 30 kilometres an hour, why not stop producing vehicles that can travel at more than 30 kilometres an hour, then no one can speed through our city streets, making them safer. We don’t need super powered SUV’s in urban spaces. Our ego might. Society don’t.

For us the autonomous car is analogous to the old tale about the high-tech pen the Americans developed to allow their astronauts to write in space, while the Russians used pencils.

In terms of mobility we have challenges that need to be met and solved, but considering why one invests in and employs technology is just as important as considering how.

Yet the why is regularly absent in such explorations of the future, or perhaps better, more contextually put: because the arguments concerning autonomous vehicles are generally led by those who advocate change, either because they genuinely believe in it or because they stand to increase their wealth and/or power though its implementation, the why is presented as given, as a when not a why, thus freeing the fantasies to consider the how.

Fantasies which receive a “general reception” and thus appear convincing, “obvious”

And in few contexts is fantasy freer than with autonomous vehicles, where much, all?, of what is presented in terms of future vehicle and urban design concepts employs the imagery and semantics of science fiction.

We hope we need not add that where employing the imagery and semantics of science fiction, in projects enabled by contemporary technology, can lead us, is very pertinently illustrated by the flying saucer in front of the Pinakothek der Moderne in Munich.

Futuro 50|50. Die Welt 2068 can be viewed in the Pinakothek der Moderne, Barer Str. 40, 80333 München until Sunday March 18th

Full details can be found at Futuro 50|50 (German only)

1. “This conclusion is too obvious not to have met with a general reception” Charles Lyell, Principles of Geology, Penguin Books, 1997

* The TUM project did assume that in 2068 people would still cycle and that shared vehicles akin to buses will be available, no one would be forced to use an individual autonomous pod. The argument here is more generally why when we have systems that work, are affordable and sustainable do we need to add several levels of cost, complexity and resource usage? And why must the buses and trams in 2068 be autonomous? A bus driver isn’t just the driver but the person responsible for the bus, someone who is there for the passengers, to offer assistance and advice, our are we to give up on responsibility and the joy in the company of our fellow humans?

** We happily accept that the arguments in favour of autonomous vehicles do include expected cost savings through, for example, reduced congestion, lower fuel costs and less accidents. Savings which in the long term could make an initial high investment viable. But we’d argue these are all savings that can be made by other means, for example, us all changing our behaviour, through better use of analogue and material technology or through more focussed and better considered urban planning concepts. The autonomous vehicle isn’t a necessity for such savings.

Tagged with: autonomous vehicles, Futuro 50|50. Die Welt 2068, Futuro House, München, Munich, Munich Creative Business Week, Pinakothek der Moderne, Technische Universität München