Transform @ S AM Swiss Architecture Museum Basel

Recycling, reuse and reappropriation are not only subjects for product design, but also for architecture, which hopefully isn’t new information, even if considerations on such (arguably) aren’t always at the forefront of architects thoughts, far less architectural planning.

Even if they (equally arguably) should be.

With the exhibition Transform the S AM Swiss Architecture Museum Basel make an appeal not only for more, better considered, recycling, reuse and reappropriation in architecture, but explore three contemporary projects which demonstrate how such can function, and thereby serving as impeti* for further projects.

Cité du Grand Parc Bordeaux by Lacaton & Vassal, Druot Hutin – left what was, right the new extension, as seen at Transform S AM Swiss Architecture Museum Basel

In context of his diploma project Ruined at the Hogeschool voor de Kunsten Utrecht Yusuf Deniz noted that “new buildings no longer get the chance to grow old. We will never experience them as ruins”, and there can little argument that contemporary architecture is only rarely planned for eternity, or perhaps better put, that contemporary architecture only rarely survives for eternity as contemporary understandings of urban planning and property development dictate demolishing buildings and rebuilding on the site at an ever greater frequency, be it in the chase for the profit margins a shiny new, high profile, project can bring, as, more or less, discussed in context of the 2016 exhibition Stuttgart reißt sich ab at the Architekturgalerie am Weissenhof, or the simple ego kick of creating a “signature” project.

A situation all the more unintelligible when one considers that the transformation and reuse of “old”, historic buildings is an accepted norm. Remembering his time in Italy in the 1930s, for example, the American architect and designer George Nelson noted, still one feels with the wonder and excitement of an American in the “Old World”, “you would be walking down a street past a 15th century palazzo but sticking out of the wall of the palazzo there would be a ruined [sic] of an arch, because it was forbidden to destroy any ruins; when you made a palazzo you built around the ruin… Then, because business wasn’t good in Rome either, a corner of this palace had been remodelled and somebody had put in an ultra-modern candy shop. So there were these three epochs coexisting in one building.”1

A scene we can all imagine today, and would accept without a second glance, yet when it comes to more modern buildings they are deemed less worthy of retention, demolishing and rebuilding being the accepted norm; and that regardless of how nebulous and shallow the reasons may be, as, for example, discussed previously in context of Egon Eiermann’s works: the ones he built, the ones he demolished, and the ones he built which others are currently trying to demolish/save.

The arguments in favour of recycling, reusing and reappropriating existing buildings, or at last some of them, can be found in Transform.

Transform: Cité du Grand Parc Bordeaux

One of the most high-profile proponents of an alternative model in recent times has been the variable French collective based around Anne Lacaton & Jean-Philippe Vassal, Frédéric Druot, a collective who have specialised in the transformation of 1960s tower blocks.

Among the group’s first projects was the Tour Bois le Prêtre in Paris, a tower block the local authorities planned to demolish and rebuild, Lacaton & Vassal, Druot thought otherwise and suggested renovating the block, while the residents remained. Among the proposed, and realised, advantages of the Lacaton & Vassal, Druot plan were lower overall costs, savings in future heatings costs and, and for us one of the central arguments, that it maintained the social fabric of the community. As opposed to ripping it apart which normal demolish/rebuild projects do. With the Tour Bois le Prêtre all residents could remain in the same neighbourhood with their established, familiar, networks, utilities and practices, and all the advantages that brings. And in higher quality flats.

In context of Transform Lacaton & Vassal, Druot and Christophe Hutin are represented by the Cité du Grand Parc project in Bordeaux, a project which saw some 530 flats in three tower blocks extended through the addition of 3.80 m deep conservatory/balcony sections which not only gives the residents significantly more space, but more light, better temperature management and therefore utility cost savings and a better living environment. And importantly, the residents can and could all stay in their flats and pay the same rent as before.

Set up as 1:1 model supported by videos the presentation of Cité du Grand Parc in Transform not only very neatly underscores the physical nature of the transformation, but also the simple construction and material solutions that helped make such possible, including the use of plexiglass windows on the exterior of the conservatories, a material previously used for greenhouse construction but which in context of Cité du Grand Parc was granted additional certification for housing.

A relatively simple step you would have thought, the project 99¢ Space by agps architecture illustrates however that it was/is anything but.

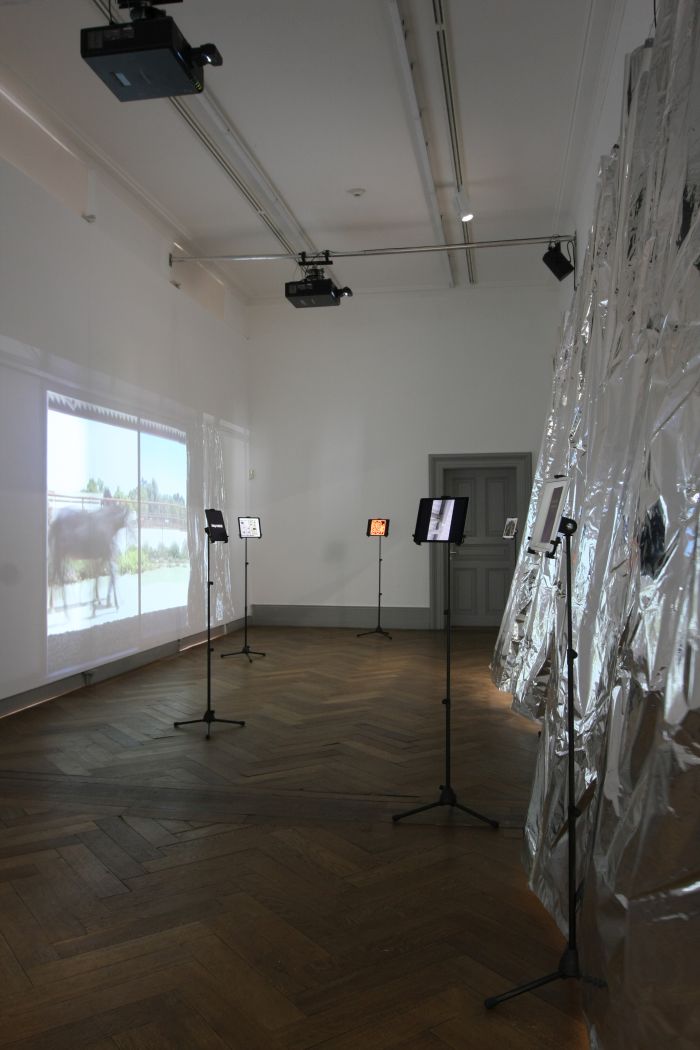

99¢ Space by Sarah Graham & Marc Angélil aka agps architecture, as seen at Transform S AM Swiss Architecture Museum Basel

Transform: 99¢ Space

Faced with the conversion of a stable/barn into a stable/barn/accommodation unit in Santa Ynez, California, Sarah Graham & Marc Angélil aka agps architecture decided to keep costs to a minimum, to explore how cost-efficiently one could build in contemporary California, achieving a mark of 99¢ per square foot, and that for all through using off-the-shelf materials from farming catalogues and industrial suppliers.

As a principle nothing new, the 1949 Case Study House by Charles and Ray Eames being one of numerous well documented examples of what can be achieved with standard, off-the-shelf, components; interesting in the case of the 99¢ Space project is on the one hand that such can/could be achieved today with such relative ease, which poses the supplementary question of why other (public) construction projects are so much more expensive……? Where one answer could lie in a second interesting aspect: not all the off-the-shelf materials conform to building regulations, including an insulating foil curtain that is certified for livestock housing but not for human housing, even if, and if we’ve understood correctly, there is no logical reason that it is but is not.

While there is obviously a lot of sense in banning products that are harmful for humans and the environment, asbestos would be a particularly good example, the logic that underlies that process needs to be transparent, clear and for all in the interests of the building’s user and wider environment. The Grenfell Tower fire being an all too stark an example of the fact that it isn’t always, that materials can be certified, and used, despite being apparently highly unsuitable for their intended location/function. 99¢ Space tending to point towards an opposite situation, of suitable products not being.

Ultimately it is a question of the intended function of building regulations and in how far building regulations are a practical tool to helping architects achieve low-cost, safe, sustainable housing, and in how far they are a bureaucratic tool whose actual function remains unclear.

The choice, and for all the source, of building materials forms the foundations, not quite literally, but almost, of the third project in the S AM Transform triumvirate.

Halle 118 by Baubüro in situ, a cross-section explaining the reuse elements, as seen at Transform S AM Swiss Architecture Museum Basel

Transform: Halle 118

According to the Transform visitor guide, around 17 million tonnes of “deconstruction material” were produced alone in Switzerland in 2016, while some 65% are recycled into new building materials no reliable data is available on how much is directly reused; and that although much of the material is structurally and materially sound and can reasonably be expected to serve many more years, and that reuse over recycling not only avoids the resource inputs necessary for recycling, but also preserves the resource inputs expended in creating the original.

In context of a regeneration project on the so-called Lagerplatz Areal in Winterthur the architects from Baubüro in situ strove to realise the vertical extension of Halle 118 through the reuse of articles salvaged from dismantled/demolished buildings within a radius of 100km of Winterthur, a realisation that includes, and amongst other components, 28 year old granite facade panels from an office building in Zürich, 12-28 year old aluminium insulated windows from Zürich and Winterthur, and a 28 year old steel outer access staircase from Zürich, in addition clay from construction sites in Canton Zürich was used for bricks and flooring and straw bales used as insulation in a construction that is 80% reuse/reappropriation.

Arguably as important/interesting as the discussion on Halle 118, is a collection of models created by students from the Institute for Constructive Design within the Architecture Department at the Zürcher Hochschule für Angewandte Wissenschaft, ZHAW, in context of a project in which they were given an inventory of materials and asked to create an extension for an existing building: as S AM Director, and Transform curator, Andreas Ruby states, a project which thereby effectively starts at the other end of architectural planning. And which we’d argue is a perfectly logical end to start from, architecture needn’t always be new, circular economies have just as much relevance in context of architecture as product design.

And if we accept that, then the time is surely good to sit down and discuss the role of architecture and architects in future society.

Halle 118 Baubüro in situ, straw insulation and local clay tiles and loam, as seen at Transform S AM Swiss Architecture Museum Basel

Urban planning and architecture not only affect the physical, visual aspects of an area, they also impact on the social, cultural and emotional aspects; consequently, just as future considerations on industrial production and consumerism must reflect on, and respond to, their impact on us and our environment, so to must future considerations on architecture. Whereby, just as the situation with regard to production and consumption doesn’t mean stopping, it does mean accepting previous generations made serious misjudgements and for all means doing better.

Based on 1:1 mock-ups of the projects, Transform presents each of the three in a different medial format thus allowing not only for a varied and alternating exhibition format which effortlessly holds the visitors attention and explains the projects in an eminently accessible fashion, but thereby provides for a very clear presentaion of both the exhibition’s position and also the protagonists arguments, arguments essentially about how we can do things better. The 1:1 mock-ups also allow for a degree of variety one would think barely possible in the S AM’s space: Cité du Grand Parc Bordeaux, as noted above, a 1:1 mock-up of a Bordeaux flat; 99¢ Space as a video installation complimented by eight tablets with supporting information; and Halle 118 as a cross-section of the new extension and a warehouse of salvaged materials.

And standing there, in the warehouse mock-up, surrounded by salvaged facades, lighting, windows, heating, plugs, screws et al, we were, once again, drawn back to what we’ve referred to before, and are certain we will do so again, as the “enduring logic and magnificence of modular construction”. We discussed such most recently in context of the Bauhaus Lab Dessau 2018 exhibition The Art of Joining: Designing the Universal Connector, for here it suffices, as we did in Basel, to imagine such a warehouse belonging to a modular building company: when new constructions are going up parts of the system go out, when buildings are being transformed, unnecessary parts returned, a continual cirucular system, and that regardless if the buildings be industrial, commercial, civic, commercial, whatever.

In many regards such is an amalgamation of the three projects presented in Transform.

Yes, such thoughts brings us back to the typisierung, standardisation, debates of the early 20th century, but then, if we’re honest, construction hasn’t moved that much since then, so why not go back to them, and yes does also involve architects accepting that their job isn’t to caress their own egos nor to establish a legacy that can be made into a hagiographic HD movie, but to work with society to create spaces worthy of life.

And thus the transform in the exhibition title isn’t a reference to the building process, but attitudes towards architecture and urban planning.

Transform runs at the S AM Swiss Architecture Museum, Steinenberg 7, 4051 Basel until Monday November 4th

Full details, including information on the accompanying fringe programme can be found at http://sam-basel.org/

1. * as ever, we fully accept impeti isn’t the plural of impetus, fervently argue it should be, that it is the more elegant option

1. George Nelson, Peak Experiences and the Creative Arts, Mobilia 265/66 1977

Tagged with: Basel, S AM, Swiss Architecture Museum, Transform