History is not only written by the winners, and re-written by those who can't accept the facts of their defeat, but history is also the story of the visible, those who are invisible having nothing to contribute.

With the exhibition Against Invisibility – Women Designers at the Deutsche Werkstätten Hellerau 1898 to 1938 the Kunstgewerbemuseum Dresden not only re-introduce nineteen, largely, forgotten female creatives, and therefore allow their contributions' to history to be recorded, but in doing so allow for new understandings of the development of design in the first decades of the 20th century, the (hi)story of the Werkstätten Hellerau, and also reflections on today's contemporary furniture design industry.

Established in Dresden on October 1st 1898 by carpenter Karl Schmidt with the aim of producing affordable furniture in tune with the evolving aesthetic and formal understandings of the period, what became known as the Deutsche Werkstätten Hellerau was one of the earliest formal expressions of the arts and crafts movement in Germany, one of the main centres in the development of Jugendstil throughout the first years of the 20th century, an important protagonist in the development of new ideas of form and functionality in the inter-war years and post 1945 one of the major furniture producers in the DDR.

That is all widely known.

As Against Invisibility very neatly explains, the Werkstätten Hellerau was also a forerunner in terms of gender equality. Something one can't say of all progressive, reformist institutions of the period, for despite the so-called reform dresses that are a compulsory component of any exhibition exploring creativity in the first decades of the 20th century, equality was often more a theoretical position than a practical reality. The (hi)stories of most design schools of the period, for example, being one of females being accepted, but rarely under the same conditions as males, one of the most popularly known examples being Anni Fleischmann (Albers) not being allowed to study art at Bauhaus Weimar, art wasn't open for females, so she joined the Weaving Workshop. While more generally individuals' attitudes weren't necessarily as reformed as the dresses, one of the better examples being that of a young Charlotte Perriand knocking on Le Corbusier's door looking for a position in his studio, "On ne brode pas des coussins ici", came the curt reply, "We do not embroider cushions here." Possibly an apocryphal curt reply, we weren't actually there, nor know anyone who was.

Which isn't to say there weren't successful female creatives of the period, there were, Albers and Perriand went on to have successful careers, the later also alongside Le Corbusier who quickly saw the error of his way, while, for example, the exhibition Art Nouveau in Nederland at the Gemeentemuseum Den Haag devoted a large section to female creatives, similarly the Grassi Leipzig's exhibition Made in Denmark. Design since 1900 or Charles Rennie Mackintosh. Making the Glasgow Style at the Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum Glasgow, both highlighting the number of females who played key roles in the development of understandings of architecture and design in the first decades of the 20th century. While also underscoring the very clear, and widely unchallenged, male dominance of the society of the day. Or there is the likes of Eileen Gray who in the course of a wide and varied career was not only in demand as a designer/interior designer, but who in addition was successful as an architect, sourced and imported carpets from artisan producers in Morocco and ran her own shop/gallery, a shop/gallery she called Jean Désert, "Jean" because a shop/gallery run by a man was more likely to be taken seriously in 1920s Paris.

Similarly the 18 designers featured in Against Invisibility not only cooperated with the Werkstätten Hellerau in the period under consideration, but were also active for other clients across a wide range of creative genres and were, according to the curators, extremely successful, many being amongst the most familiar, in demand, names of their time.

A claim the exhibition underscores.

In form of a linear Watson-Crick double helix Against Invisibility presents two stories running parallel in a single strand: through the middle of the exhibition space runs the history of the Werkstätten Hellerau, a story told in context of the wider developments of arts and crafts of that period, and including notes on elements such as the establishment of Hellerau Garden City by Schmidt, the role of interior design commissions in the company's success, or the numerous national and international exhibitions in which they participated; on either side of the central strand run the biographies of the 18 selected designers plus that of the photographer Hedda Reidt who worked with numerous product/consumer good clients, including between 1928 and 1944 the Werkstätten Hellerau, the interweaving of the stories allowing for the telling of numerous subplots along the way and thereby effortlessly creating a nicely paced and easily comprehensible narrative. A narrative supported by examples of the selected protagonists works, again those objects for Werkstätten Hellerau along the central axis, those with/for other clients running parallel.

And thereby an exhibition format which very pleasingly brings the protagonists and their work equally to fore, and while in no way allowing for fulsome reviews of the individuals oeuvres it does enough to allow one, to at least believe, to have understood their respective oeuvres, you haven't, for that each is presentation is too brief, but you have been introduced to both protagonists and their work.

And one can only be introduced to that which is visible, which has been retrieved from its anonymity.

With its focus very much on the protagonists, their lives, times and their relationships to Werkstätten Hellerau/creativity of the period, the one question the exhibition doesn't directly answer, while continually approaching such an answer, is why the 19 became invisible?

Is the question relevant?

On the one hand arguably not, one could argue that in the confusion of the war years and the immediate post-war focus on rebuilding and reorganising, not only did a great many biographies get lost, but an awful lot of careers were disrupted, a great many designers, male and female, were denied the chance to follow their natural progression and become the household names their talents arguably demanded, and instead drifted into an invisible anonymity. Tragic, but an inevitable consequence of the period.

However, female creatives found themselves at a particular disadvantage in the (still) heavily patriarchal society of the immediate post-War decades, including those years when people did start researching the pre-war (hi)stories. Or perhaps more accurately put (his)stories, because that's where the focus was. Again we'd introduce an Eileen Gray as an example, a creative who despite all her achievements vanished post-war, only re-emerging in the 1970s, and that more through chance than dedicated academic research.

Consequently the popular story of Jugendstil, Art Deco, the Modernist Avant-Garde etc contains a Y chromosome that tends to primacy.

Which as any geneticist will tell you, is rubbish.

And a situation Against Invisibility aims to rectify.

The protagonists in Against Invisibility have/had the additional disadvantage that post-War, Dresden found itself, as with Burg Giebichenstein Halle and the Bauhaus locations Weimar and Dessau, in East Germany, and thereby on the one hand outwith the easy reach of researchers in Western Europe, and on the other, subject to the whims of East Germany's famously very idiosyncratic and individual understanding of history, and the conceivable, though unproven, notion that the DDR authorities weren't keen to promote something as liberal, free-thinking and, ultimately, comfortably middle class, as the Werkstätten Hellerau. Yes, arguably concentrating on successful, emancipated females could have been considered a good subject via which to distinguish the DDR from the imperialistic West. But then the list of things the various DDR governments did when the opposite would have appeared more logical is long. And a subject for another day. Finally it is always worth noting that, in our understanding, the (hi)story of inter-war design and architecture is largely dominated by the fascination the MoMa New York had with Bauhaus and the status generally afforded the likes of Mies van der Rohe or Walter Gropius in America. Everything else, as in everything else, being but a side story to the Bauhaus legend. Again we have no evidence for our position, but.....

And while the infamous B wasn't actually mentioned by the curatorial team at the opening, it was very clear that the timing of the exhibition, just before the Bauhaus 100 lunacy that awaits us next year fully kicks off, was a deliberate, almost guerilla, act, a potent and clear reminder to the world that Dresden as a city and Hellerau as a concept were far ahead of the illustrious school on the Ilm.

Not least in terms of gender equality.

Quite aside from returning the identity and personality to its 19 protagonists, making them visible for future generations, and allowing for a platform to analyse and consider their work, to, if you will, give credit where it is due, Against Invisibility also allows for a moment of reflection on our own enlightened times. As Kunstgewerbemuseum Dresden Director Tulga Beyerle noted, whereas in comparison to her student days, and certainly when viewed in context of the period 1898-1938, the female:male ratios at design schools may have reached, more or less, parity, females amongst the higher echelons of global design remain a rarity. And certainly our own empirical experience tends to underscore such a position: whereas in the course of our #campustour visits to design school exhibitions there is pretty much a 50/50 chance that any given project will be by a female student, once one gets into the commercial world the situation is very different. Or put another way, and as a thoroughly random, and unscientific, example, from the 38 projects featured in our 8 2018 trade fair High Five!! posts...... 3 were by females, and 5 by a female/male design duo. Or put another another way, from a total of 47 designers featured, the female:male ratio is 8:39. Or circa 1:5

Call us chauvinists if you want, we can defend ourselves, and defend each and everyone of our selections, either to or not to include a project, on the basis of our understandings of design, and also very quickly and deftly shift all the blame to the manufacturers, we can only post on that which exists.

Which is of course a central theme of Against Invisibility.

According to Against Invisibility curator Klára Němečková, between 1898 and 1938 the Werkstätten Hellerau cooperated with a total of 54 female and 130 male designers, at 1:2.4 a ratio double our own example, and one higher than that achieved from a quick, non-representative, far less scientific, review of a selection of contemporary furniture manufacturers, the "designers" page of most all websites being predominately male. The only exception we could have quoted was a recent, no longer existent, incarnation of the, appropriately enough, Thonet Design Team, which had, then, a 5:2 female:male ratio.

But is the fact that a furniture manufacturer in 1938 had a higher female:male designer ratio than many a furniture manufacturer in 2018 acceptable?

No.

Against Invisibility tends to argue we shouldn't be surprised.

In addition to presenting personal documents, letters and photographs which discuss in more detail the reality of the protagonists lives, including the challenges and prejudices they faced in the society of the day, the decisions and compromises that had to be made in balancing personal and professional lives, Against Invisibility also invites visitors to participate in a little game: throughout the exhibition are distributed 10 cards, 7 ask visitors to imagine themselves in the role of a female designer of that period and answer questions such as, for example, what do you do if you aren't allowed to undertake the sort of training you want to, or to consider the type of designs you would realise in a particular context, while a further 3 hand you your fate, for example, although as a lesbian you are unable to marry your partner, your single status does mean you can teach. Married ladies couldn't. At the end of the exhibition you discover how visible you may or may not have been, but much more importantly have, hopefully, a greater understanding of the challenges faced by female designers of the period, the extended relevance of the Werkstätten Hellerau beyond merely being a furniture producer, the importance of retrieving the Hellerau female designers from their anonymity. And helping you move towards an answer to the question why the 19 became anonymous. Including the extrapolated question of the visibility of contemporary female designers, of the hurdles and challenges faced by contemporary female designers, and how the design landscape of 2018 will be understood when reviewed in 2098........

That the cards, in contrast to the bilingual German/English information panels, only exist in German does somewhat limit the experience for non-German speakers, but only somewhat, and for all demands paying closer attention to the exhibition, in itself no bad thing. Not that we can imagine producing the cards in English would be particularly troublesome.

With its very clear and logical exhibition design, Against Invisibility allows for an easy entry into the subject(s), and continues to hold your interest, something helped not least by the active decision only to focus on a third of the possible 54 female designers, on a selection that, and here one must trust the curators, provides for a realistic summation of the complete picture, and which importantly stops the exhibition from becoming over-taxing and monotonous, allowing for a much more relaxed, unhurried, when every bit as informative and entertaining experience, and one which leaves enough space for your own thoughts.

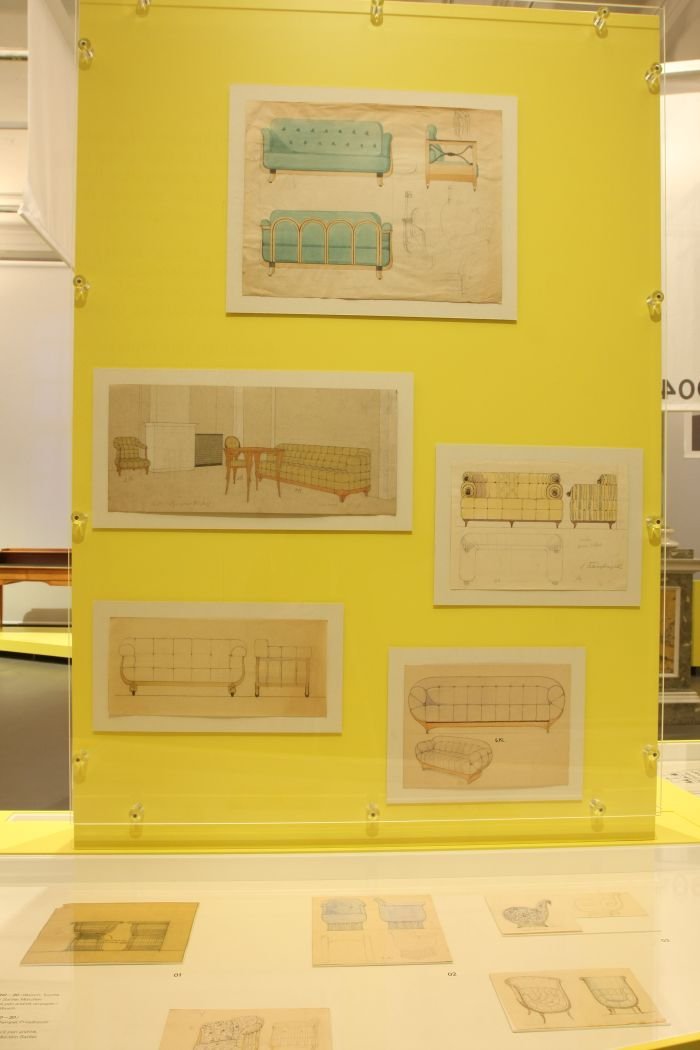

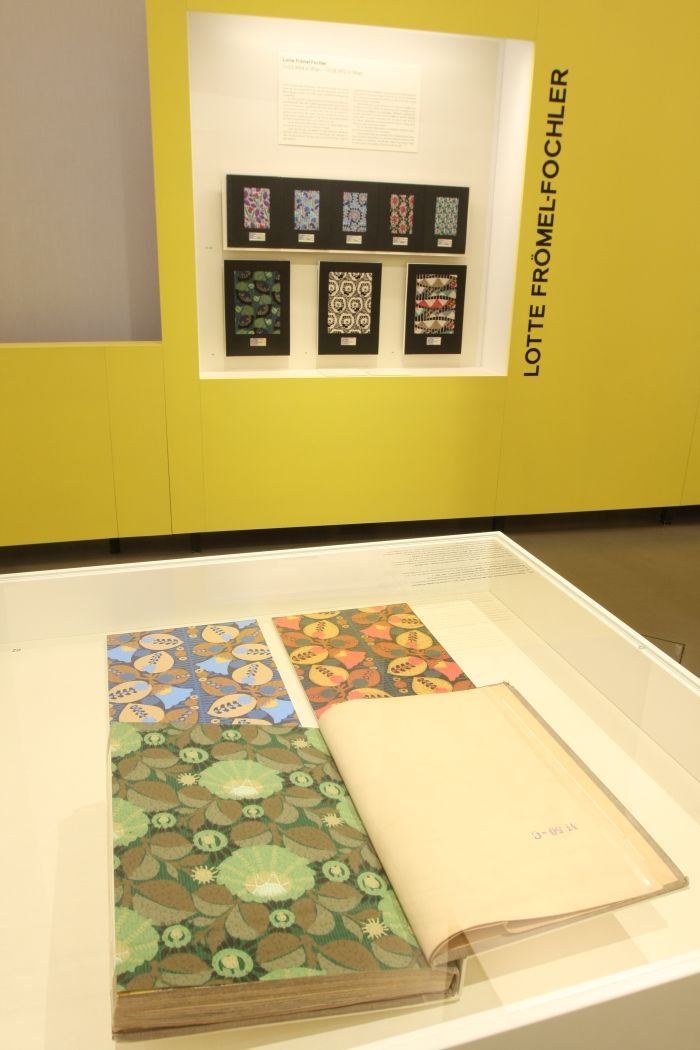

Similarly while keepers, guardians, of the largest collection of Hellerau objects, the curators pleasingly chose not to overfill the Japansiches Palais exhibition space with objects from that collection, deciding in many regards that less is more, while still achieving a wide mix of creative genres including embroidered cushions, weaving, textiles, toys, ceramics, furniture, and a reform dress, all backed up by sketches and similar supporting documentation; and a presentation from which we were particularly taken by a series of textile/carpet samples by Ruth Hildegard Geyer-Raack, the furniture designs of Margarete Junge, and pretty much everything presented by Gertrud Kleinhempel, but for all a 1910 chair, an absolutely audacious piece of work which toys with the motifs of the chair design of antiquary, mercilessly almost disrespectively so, but also with a self-confident reduction and reforming, and in doing so very neatly highlights what Greco-Roman-Etruscan chair designers could learn form the new generation. And thereby is not only a delicious piece of furniture design in itself, but a nice personification, instantly accessible explanation, of the influences of classical architecture and design that were so prominent in the early 20th century, and so important for the subsequent development of international modernism. The 1905 chair by Gertrud Kleinhempel ain't bad either.

However the principle focus of Against Invisibility isn't the works, nor the designers of the works, nor the institution that links the designers of the works, nor the cultural epochs in which the institution that links the designers of the works existed, but much more is about completing the story of the epochs, of the institution and of doing that through the introduction of the, until now, unseen, or at least only rarely acknowledged, designers and their works.

And for all stands as an important reminder of what we can learn from the invisible.

Against Invisibility – Women Designers at the Deutsche Werkstätten Hellerau 1898 to 1938 runs at the Japanisches Palais, Palaisplatz 11, 01097 Dresden until Sunday March 3rd

Full details, including information on the accompanying fringe programme can be found at https://kunstgewerbemuseum.skd.museum/against-invisibility