"I first saw resilient tubular steel furniture designed by Professor Mies van der Rohe in September 1927 at the exhibition "Samt und Seide" in Berlin, objects which made a very deep impression on me, because I felt and saw that here, for the first time, was a meaningful way to utilise the forces inherent in tubular steel." Anton Lorenz, 27th March 19391

Because discussions on the steel tube furniture that, in many regards, characterises the inter-War period tend to focus on the designers and architects, it can be all too easily forgotten that without those who identified the potential, those who not only understood the significance of the new developments of the period, but had the requisite skills to bring the ideas of a, relatively, small group of creatives to the market, steel tube furniture may not today enjoy the fascination and following that it does.

Certainly wouldn't stand as characteristic of the inter-War period.

Amongst those who played a leading a role in such developments was the Hungarian born designer and entrepreneur Anton Lorenz. With the exhibition From Avant-Garde to Industry the Vitra Design Museum Schaudepot not only explain Anton Lorenz's role in the development of inter-War furniture, but also his post-War contributions to an, apparently, contradictory furniture genre......

As previously discussed, born in Budapest on May 13th 1891 Anton Lorenz, and his opera singer wife Irene Schmotczek, moved in 1919 to Leipzig, and subsequently in 1922 to Berlin, where Lorenz established himself as a locksmith and metalworker, and most importantly, in 1927 was introduced to steel tube furniture. Prior to his aforementioned acquaintance with Mies van der Rohe's cantilever chairs, Lorenz had seen works by Marcel Breuer in the office of Breuer's associate, business partner, and fellow Hungarian, Kálmán Lengyel, and subsequently not only joined the board of Breuer and Lengyel's Standard Möbel company but undertook experiments in his own workshop to further develop the technical, material, aspects of Breuer's work, experiments which, as he describes, were intended to bring the same resilience to Breuer's designs that he had felt in Mies's.

In January 1928 Standard Möbel began selling Breuer's designs, and in the same year Thonet began producing further steel tube designs by Breuer; that Standard Möbel enjoyed, at best, middling success, and Thonet were a much larger, established, manufacturer, Thonet acquired Standard Möbel in 1929, thus, and logically, uniting the Breuer portfolio under one roof.

Following the sale of Standard Möbel Lorenz both established his own company, Deutsche Stahlmöbel, DESTA, and acquired on behalf of Mart Stam copyrights for Stam's cantilever chair designs; thus allowing Lorenz in 1930 to sue Breuer and Thonet for infringement of Stam's copyrights. Which is just one of the most joyously absurd and improbable moments in the (hi)story of furniture design, and a process Lorenz/Stam won, meaning that since 1932 Mart Stam has been the acknowledged holder of the artistic copyright to the quadratic cantilever chair.

That Lorenz/Stam won was, as we implied in an earlier post, arguably, assisted by a slight naivety on Thonet's part, an oversight in contractual negotiations that in many regards stands juxtaposed to the iron-fastness of Thonet's 19th century patents, patents which, in effect, allowed the company to establish its dominant position. And an understanding of the importance of patents Lorenz demonstrated he understood, for all in that he, in many regards, beat the masters at their own game.

In 1933 Anton Lorenz closed DESTA and joined............ Thonet, serving between 1933 and 1935 as, and somewhat logically, Head of Industrial Property Rights, before spending the second half of the 1930s in closed contact with the likes of Mies van der Rohe, Hans Luckhardt, Heinz Rasch, Lily Reich, László Moholy-Nagy and Marcel Breuer. And that largely, though not exclusively, in context of patents, copyrights and licensing agreements. Anton Lorenz being very much a facilitator of the period, the go-to person in terms of contractual questions.

Finding himself in America at the outbreak of the Second World War Anton Lorenz choose to remain there, and where post-War he became involved in the development of a genre of furniture that, all logic tells us, couldn't be further removed from the steel tube of inter-War Europe: upholstered reclining armchairs.

However, as Anton Lorenz: From Avant-Garde to Industry underscores, in furniture one should never confuse the final form for the initial idea, nor forget that designers are always the sum of their experiences and past projects, nothing arises in isolation.

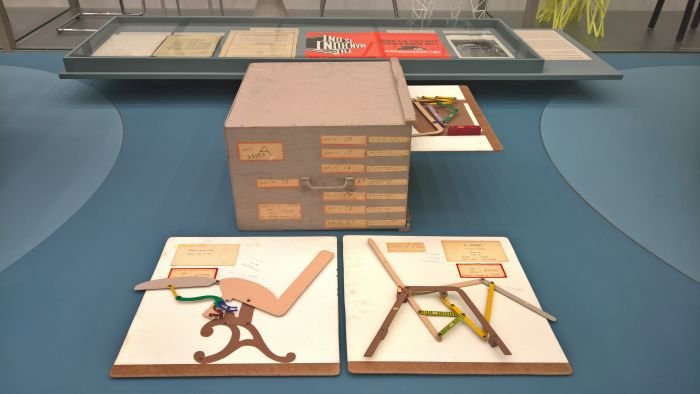

Pleasingly for an exhibition about the (hi)story of furniture design, From Avant-Garde to Industry is not really about the numerous furniture objects on display, interesting and engaging as they are, the much more important component of the exhibition is the innumerable documents, letters, pamphlets and photographs presented.

Pleasingly on the one hand because the documents et al allow for a discussion on the development of steel tube furniture that goes beyond the formal and technical aspects, and instead highlights the business aspects, the companies and the defining moments that accompanied its development; aspects arguably colder and harder than the steel tubing itself, but no less important in the (hi)story of steel tube furniture, for, and as design theoretician Max Borka once told us, "design stands on two feet, one commercial and one cultural", you can have all the avant-garde ideas you want, at some point you need to monetise them, need the industry.

Pleasingly on the other hand because the documents et al allow for a succinct, direct, explanation of how from the early 1930s onwards Lorenz's work with steel tube furniture led him to the study of ergonomics, including a cooperation with the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Occupational Physiology in Dortmund aimed at determining an optimal reclined position. And research which saw Lorenz cooperate with Hans Luckhardt to create reclining chairs; chairs which in many regards evolved early steel tube furniture by adding a new level of functionality, a new level of mechanical complexity.

Pleasingly on the all important third hand because the documents et al allow one to follow how that research on ergonomics in 1930s Germany led Anton Lorenz to develop upholstered reclining armchairs in 1950s America, and how that development can be understood as a continual escalation of an idea, one that moved it ever further away from where it began, yet without ever rejecting that which had come previously, rather built upon it, literally, and understanding it anew. In 1926 Breuer predicated that one day we would sit on a "resilient column of air", by 1950 Lorenz's interpretation of that column was as upholstered. One was however still floating.........

And pleasingly on the rarely reached, often believed mythical, fourth hand because the documents et al allow one to better understand how important patents are in furniture design, that true innovation in furniture design is patentable, and something discussed in the pages previously not only in our design calendar post on Thonet relinquishing their bentwood patent in 1869, but also, for example, the side flexing shock mount that is so important in the Eames Lounge Chair, or the Wilde + Spieth height adjustment system developed in the 1940s for, and still used in, Egon Eiermann's chairs. Beyond Lorenz's dispute with Thonet and those in context of his work in America, From Avant-Garde to Industry further underscores the importance of patents through, for example, a ca. 1934 catalogue from Japanese plagiarists, a catalogue which also very neatly intimates an early Japanese interest in the works of European Modernism, and two 1933 cartoons from a Danish newspaper referring to a patent dispute between Lorenz and Fritz Hansen, newspaper cartoons which tend to imply the patent dispute was newsworthy.

In addition there is an 1959 American newspaper cartoon featuring a reclining lounger sent to Lorenz by his lawyer and which, and with reference to the mechanism displayed in the cartoon recliner asks, "Notice the double four-bar linkage. Could this be an infringement?" Presumably it wasn't, one suspects had it been an Anton Lorenz would have sued. And the bigger question is, if the lawyer also sent an invoice for the time taken to develop his little joke?

Important and informative as the innumerable documents, letters, pamphlets and photographs are, as an exhibition From Avant Garde to Industry wouldn't work without the numerous interesting and engaging furniture objects on display; our light-handed rejection of them above being purely in interests of rhetoric. Apologies.

Starting with those steel tube objects which have largely come to popularly define the period, including works such as Mart Stam's W1 from 1926, Breuer's B 32 from 1928 and Mies van der Rohe's MR 10 from 1927, that work in which Lorenz first felt and saw a "meaningful way to utilise the forces inherent in tubular steel", the presentation moves on to a couple of key works on the way from steel tubing to the upholstered reclining armchair: the 1938 Siesta Medizinal and an aircraft seat from 1937.

Arising from Lorenz's research into ergonomics and developed from the mid-1930s onwards by Lorenz in cooperation with Hans Luckhardt, the Siesta Medizinal was produced by Thonet and marketed as both a domestic recliner but also, and as the name implies, as an object for medicinal, therapeutic, institutions; and according to From Avant Garde to Industry during the Second World War Thonet focussed almost exclusively on production of the Siesta Medizinal for military hospitals, if you will, it gave the company a market at a time when most others had collapsed. And equally importantly served as a precursor for Lorenz's BarcaLoafer, the first result of his post-War cooperation with American manufacturer Barcalo, a reclining chair created in tubular aluminium, and which thus bequeaths it a visuality similar to the steel tube of inter-War Europe, but for all a work whose commercial success allowed Lorenz to establish himself in America. A success indicated not only by the sales figures of the BarcaLoafer, but also by the licensing agreements struck with other manufacturers and which saw it also sold as the Superloafer or Gayloafer.

Parallel to the development of the Siesta Medizinal, and based on the research at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Occupational Physiology, Hans Luckhardt developed a chair for Air France, and a work which links nicely into both Bauhaus_Sachsen at the Grassi Museum für Angewandte Kunst Leipzig and Four “Bauhausmädels” at the Angermuseum Erfurt: a letter from the Wagner-Reichardt weaving mill in Erfurt referring to a discussion with Luckhardt, Anton Lorenz and Mart Stam in the Grassi Museum in context of the 1938 Leipzig Spring Trade Fair concerning the use of the Eisengarn textile Margaretha Reichardt had developed during her time at Bauhaus Dessau, for aircraft seating. There is sadly no indication if it Luckhardt ever used it, the years quoted tending to imply he didn't, but Eisengarn was certainly developed for just such heavy duty use. What is clearer is that the chair was tested by Air France on night flights between Paris and Algiers, one presumes as one of the earliest examples of a reclining aircraft chair, one specifically intended to be (comfortably) slept in, and is an absolute a monster of thing, as in a genuine beast of a chair. Standing next to it in the Schaudepot it is hard to believe any plane equipped with more than one could have taken off.

But is still a reserved and reflective item when considered in context of the upholstered reclining armchairs that would come.

In many regards evolved from the BarcaLoafer, certainly in terms of the technology and mechanics hidden beneath the upholstery, Anton Lorenz's BarcaLounger was launched by Barcalo in 1950 and marketed, in a slightly adapted form, from the late 1950s expressly as a TV lounger, and, and as with the BarcaLoafer, was, or better put, the technology was, licensed to other manufactures who marketed it as the equally improbably monickered Stratolounger, Rock-A-Fella or La-Z-Boy. Yet regardless what it was called is an object that elicits strong feelings of longing in some and an equally strong despondency in others.

And as the curators note, an object which has only little to do with Mid-century American Modern. And we for our part would add there is a certain humour in the fact that a man who did so much to promote steel tube furniture, who did so much to help establish new formal aesthetic understandings, to help establish understandings of furniture, interiors, modernity that allowed the likes of Eames, Saarinen, Nelson et al to be able to push their own understandings of the same, that such a man should subsequently have done so much to set a contraposition to Eames, Saarinen, Nelson et al. But it does also remind us that when discussing any given moment in furniture design history one is always blocking out objects that don't fit in your narrative. As, for example, Moderne am Main 1919-1933 at the Museum Angewandte Kunst Frankfurt demonstrates, wooden chairs were more important to the inter-War years than steel tube chairs. Similarly post-War American furniture isn't just that which the MoMA New York presented. And it's important to occasionally be reminded of such. To be reminded that one's view is always blinkered. Which, yes, does sound like a metaphor......

In addition to providing a very well founded introduction to the life and work of Anton Lorenz From Avant-Garde to Industry also allows for rarely seen perspectives on the development of furniture throughout the 1920 and 1930s, including numerous "lost" designs by the likes of Marcel Breuer, Lilly Reich, Alvar Aalto, Mart Stam, and, and most intriguingly, a reference in a 1953 letter from Lorenz to Mies van der Rohe to "Plastic-Shell Chairs" Mies van der Rohe had presumably designed and Lorenz was keen to pitch to Herman Miller.

Then there is Lorenz's own glass chair design, an absolutely preposterous proposition, and one which in effect sets an upholstered armchair atop an angled sheet of glass. Presented in From Avant-Garde to Industry as photos, photos whose perspective arouses a little suspicion, as a work visually stunning, but as an object it not only can't work physically but morally shouldn't ever be allowed to.

One of the most in-depth exhibitions we've seen in the Vitra Design Museum Schaudepot, aside from providing an all too rare insight into the upholstered reclining armchair, a genre you needn't approve of, but should concern yourself with in terms of better understanding the (hi)story of furniture design, for what, for example, is an Arne Jacobsen Egg if not a upholstered reclining armchair, an upholstered sitting machine to misquote Josef Hoffmann.......... Anton Lorenz: From Avant-Garde to Industry also allows for a more probable, realistic, telling of the narrative of the development of steel tube furniture, one devoid of much of the romanticism, fetishising and mythology that normally surrounds such considerations.

And is an exhibition where despite the depth and variety of information presented, one never feels overtaxed, one always feels as if one is just at the start, and a situation which means that for us From Avant-Garde to Industry feels very much like the Vitra Design Museum feeling their way forward to a more major "Lorenz" exhibition; they are custodians of the Lorenz archive and, for us, From Avant-Garde to Industry feels very much like a first attempt to fully understand what they have and brainstorming how it could be presented.

Which isn't to belittle From Avant-Garde to Industry. Far from it. As an exhibition it has its own very clear and comprehensive flow, is a coherent, self-contained and well rounded presentation that competently and entertainingly presents the subject; but one can feel the wider contexts, can feel how the story could be expanded and recontextualized both through the innumerable questions posed by the documents, letters, pamphlets and photographs and through the 100+ years of furniture history that surround you in the Schaudepot, you can actually see where the narrative could be developed. Automatically do so yourself. And we'd argue that as we approach the centenary of the steel tube cantilever a deeper investigation that goes beyond the simple, and largely incorrect, associations currently popularly entertained is necessary. Or put another way, in From Avant-Garde to Industry we, felt and saw that here, for the first time, was a meaningful way to tell the (hi)stories inherent in tubular steel.

But that's all supposition on our part, we have no inside information, no-one ever tell us anything, we are merely wishing aloud; and independent of such thoughts, Anton Lorenz: From Avant-Garde to Industry is a most enjoyable place to begin to understand one of the major players in the development of steel tube furniture. And upholstered reclining armchairs.

Anton Lorenz: From Avant-Garde to Industry runs at Vitra Design Museum Schaudepot, Charles-Eames-Straße 2, 79576 Weil am Rhein until Sunday May 19th

1Anton Lorenz: report on the development of a cube-shaped chair produced resilient, cold-bent steel tubing, 27th March 1939, presented in exhibition

Full details can be found at www.design-museum.de/anton-lorenz