To paraphrase the title of the recent exhibition at the Deutsche Architekturmuseum, with the Neues Frankfurt project the team of architects and urban planners around Ernst May and Ludwig Landmann sought to develop new housing for new humans.

With the exhibition Wie wohnen die Leute? the Historisches Museum Frankfurt explore the contemporary reality of the Neues Frankfurt estates and thereby the new housing of then in context of the new humans of today.

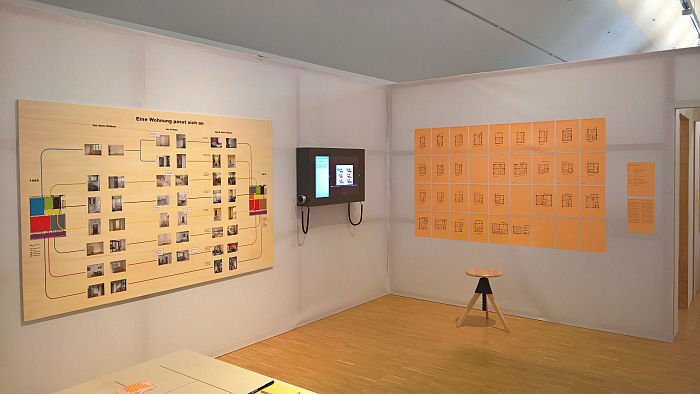

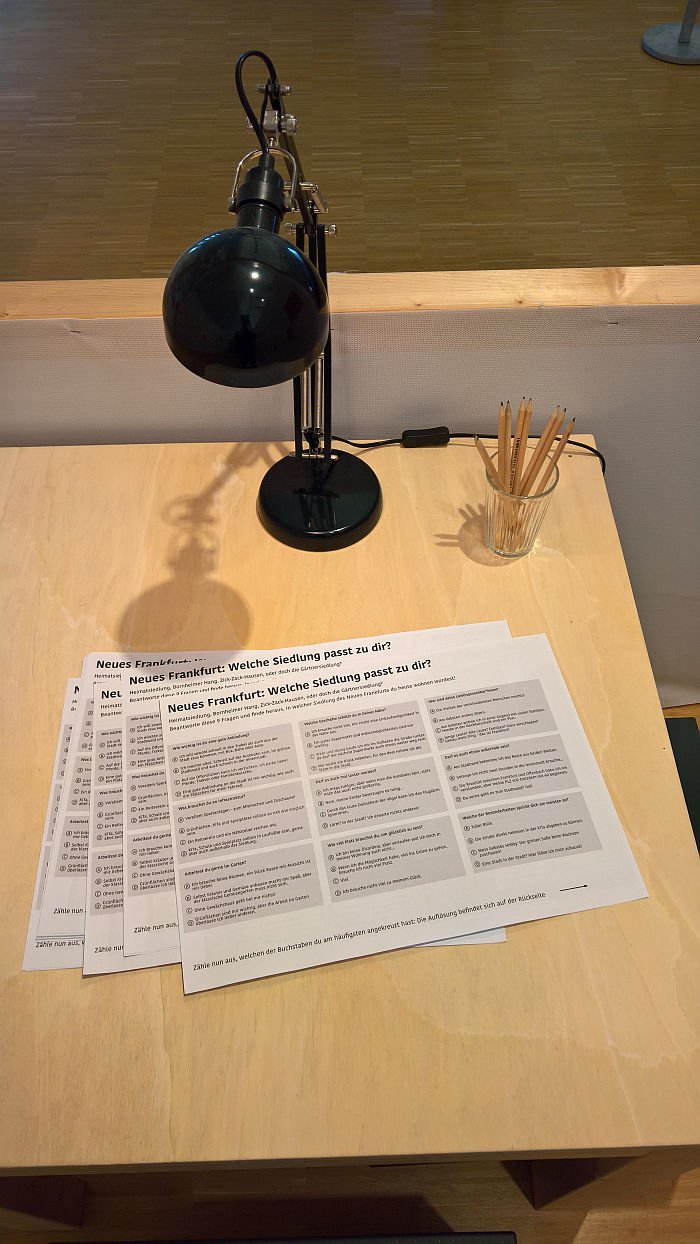

Realised in conjunction with the aforementioned New Human, New Housing: Architecture of the New Frankfurt 1925–1933 at the Deutsche Architekturmuseum and Moderne am Main 1919-1933 at the Museum Angewandtekunst Frankfurt as a triumvirate of exhibitions exploring the Neues Frankfurt urban planning programme of the 1920s and 1930s from three different perspectives, Wie wohnen die Leute? - How do people live? - is based on a project undertaken in Summer 2018 which saw the Historisches Museum's Stadtlabor, a participative, mobile, research platform, visit 19 of the Neues Frankfurt estates and where they not only charted and recorded contemporary life, but also sought to explore the contemporary reality in and on the estates, and that through projects undertaken by and with, principally but not exclusively, local residents; if you will, explored the estates with the aid of the experiences and understandings of those who live with the estates on a daily basis.

And although superficially Wie wohnen die Leute? is about the contemporary reality in and on the Neues Frankfurt estates, that is, and as with all superficialities, only superficial; much more, Wie wohnen die Leute? takes the question posed in the exhibition title as the starting point for reflections on both the evolution that the housing/estates have undergone in the decades since their creation and the contemporary relevance of that which was achieved in the inter-War years.

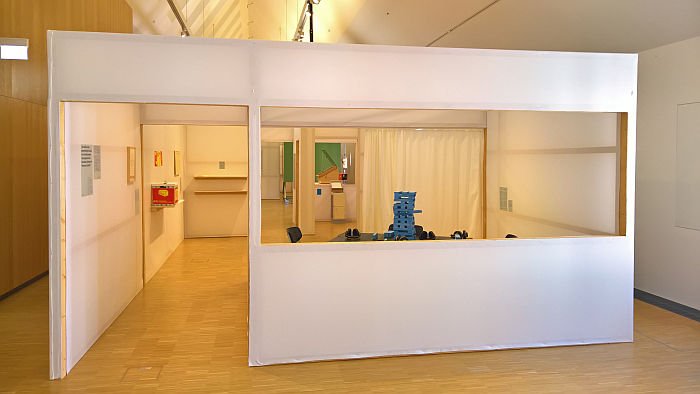

To this end Wie wohnen die Leute? features an exhibition design based around 1:1 scale models of four of the eighteen standardised housing types realised in context of Neues Frankfurt, or at least the ground floors, not all Neues Frankfurt housing was single storey flats; and 1:1 scale models which in addition to representing four different building types with four different functions in the Neues Frankfurt project, also represent four different components of the exhibition narrative and thus instigate four different discussions and discourses. And thereby exits as a very intelligent, and satisfying, exhibition design concept which allows in the (relatively) limited space available for both an understanding of the spatial realities of the Neues Frankfurt housing as well as the more practical, social and theoretical aspects.

And an introduction to the language of Neues Frankfurt.

EFATE 7.115, ZWOFADOLEI 2.40/3.46, MEFAGANG 2.28 & MEFA 3.42 may sound like the sort of things the United Nations is urgently attempting to ban; is however the singular nomenclature of the Neues Frankfurt housing, specifically the four standard housing types represented in Wie wohnen die Leute?

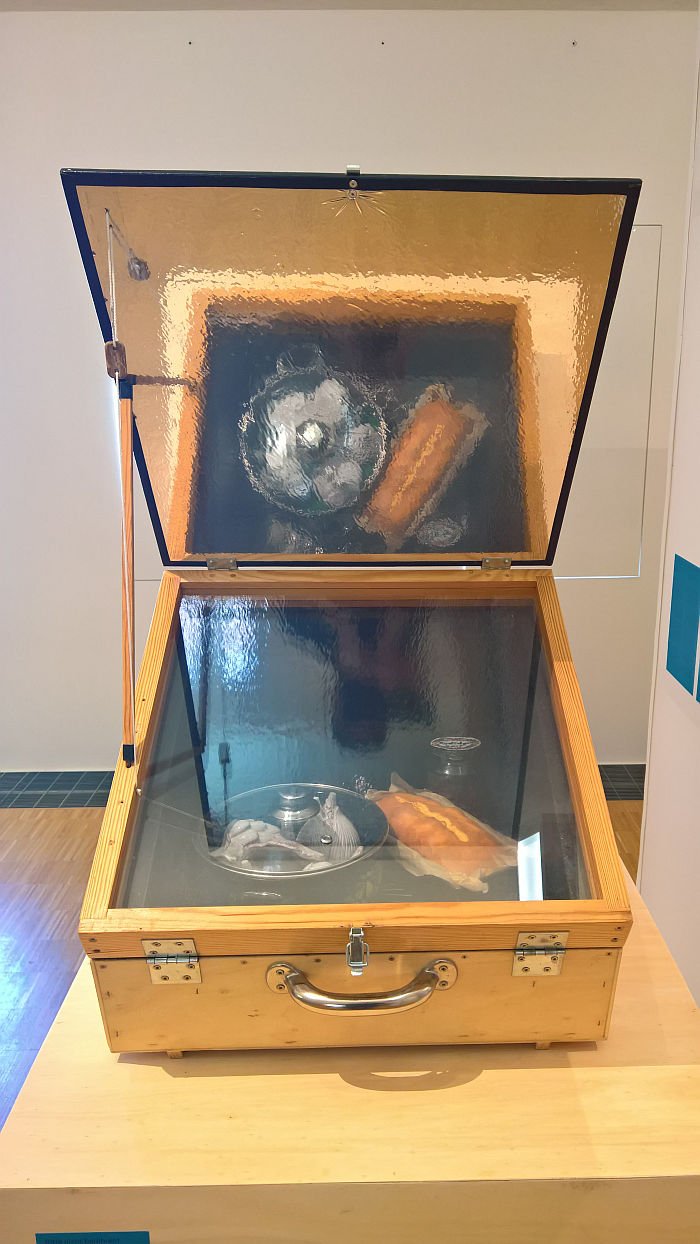

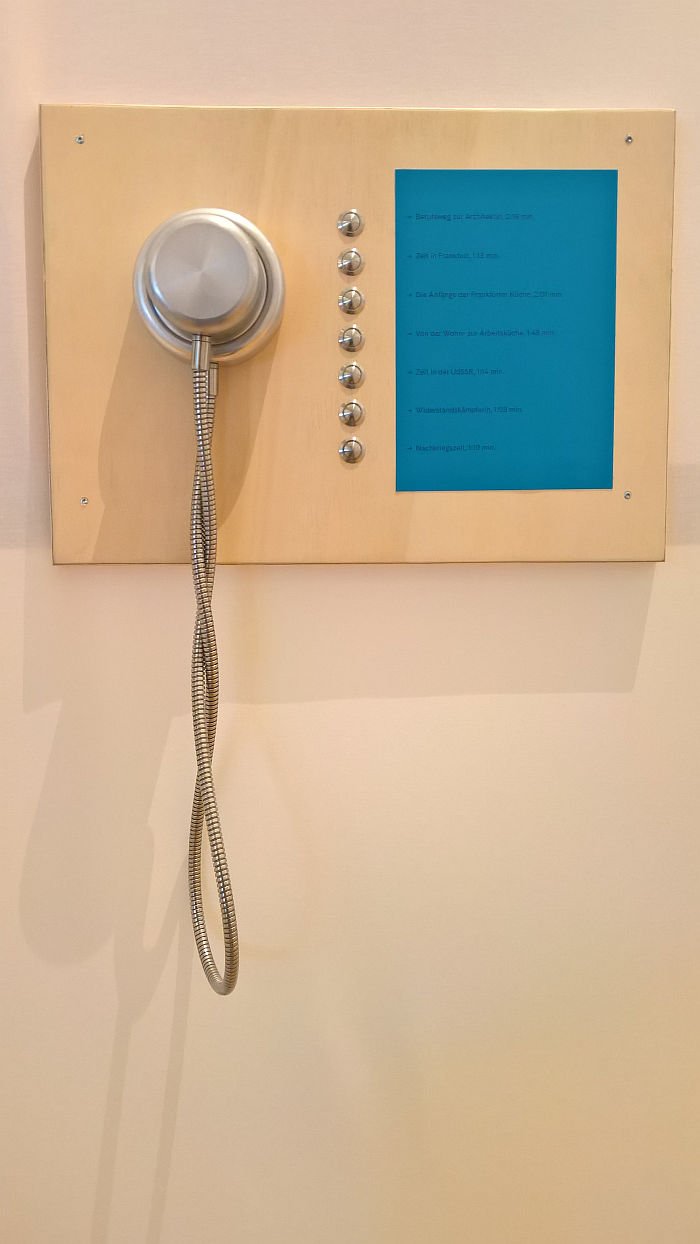

Although as an exhibition Wie wohnen die Leute? has no formal starting point, the most logical place to begin is in EFATE 7.115: but fear not, EFATE not defining a contemporary reality in which Californians control our digital, and thus personal, destiny, but the much more prosaic German acronym/initialism for EinFAmilienhaus mit dachTErrasse [Single family house with roof terrace], 7 being the number of rooms and 115 the floor space in square metres. As such an EFATE 7.115 is/was a sizeable property. And a property type exploited in Wie wohnen die Leute? to explore life on housing estates, then and now. Then as depicted by, and amongst other projects, aerial photos of the estates in their early days or an introduction to the colour schemes employed; now as visualised by projects such as Thresholds and Transitions by students at the University of Applied Arts Frankfurt which explored movement through the estates as exemplified by observations made at the entry points to the Römesrstadt estate. Then and now being linked by the likes of Roswitha Väth's exploration of the developments and evolutions of the Nonnenpfad estate over the centuries, and through that most enduring popular symbol of Neues Frankfurt: the Frankfurter Küche. Specifically Laura J Gerlach's project The Library of the Frankfurter Küche in which she creates 360° panorama views of intact, original, kitchens, a project which was also shown in Moderene am Main, and which for Wie wohnen die Leute? has been adapted to a more analogue presentation format, And a project which succinctly and pleasingly explains how residents adapt and adjust the "basic", standardised, kitchen to meet their own specific, contemporary, individual, needs.

And a symbol which is returned to throughout the exhibition; not as a defining factor, but simply because the Frankfurt Küche is not only an object so, uniquely, closely related to Neues Frankfurt, but also as a project stands in many regards representative of the questions of functionality of the new housing of the age, of the way the new housing in Frankfurt was designed for the new people of Frankfurt and beyond. Understandings of functionalities, needs and movement which, as Wie wohnen die Leute? notes, were decided by Ernst May and his team independent of the future residents: there were no collaborative planning workshops in late 1920s Frankfurt. A sensible urban planning process, one which allows for the realisation of new ideas rather than repetitions of the familiar? Or are collaborative processes the better option? And when, then into the finer details or remaining in more general terms? Give residents that which architects believe they need or that which they believe they need? In the course of Wie wohnen die Leute? such questions are regularly reflected on from both historic and future perspectives.

And are important questions because as the discussion on Neighbourhoods in the, well, neighbouring, house, MEFA* makes clear, the context in which housing exists is subject to developments, planned and unplanned; the architect and urban planner supply that which they understand as necessary and/or that which residents demand as necessary, but then social, cultural, economic, political, demographic evolutions change the context in which the estate exists and by extrapolation the needs of the residents. A process represented in Wie wohnen die Leute? by projects such as Auf der Veranda by Melanie Herber which reflects on the role of the veranda, or Wildgarten which documents the establishment of an adventure garden for children. And a reference to gardens that reminds of the central importance gardens and green spaces played in the development of not only Neues Frankfurt but inter-War housing in general, and something discussed in Wie wohnen die Leute? by a garden shed: specifically a 1:1 model of the sheds developed for the Neues Frankfurt allotments as a space for discussion and reflection on the role of gardens and urban green spaces, then and now. "Do gardens have to be beautiful?" asked once Leberecht Migge, one of the leading protagonists of inter-War garden and spatial design, "No! First of all gardens must be there and nothing more"

And today?

The smallest house in the exhibition, MEFAGANG**, two rooms and 28 square metres, is, most appropriately, home to one of the more contemporary themes, a question that also occupied the the Neues Frankfurt team, and of which MEFAGANG was a response: how do we organise sufficient affordable housing? How do we achieve housing which, to quote Ernst May, helps the occupants achieve "a life worth living"

A discussion undertaken in Wie wohnen die Leute? by projects as diverse as the 1928 film "Die Frankfurter Kleinstwohnung" which introduced the new, small, apartments of the Praunheim estate to a public (still) unfamiliar with such homes/concepts; considerations on an extension of the Frankfurter Küche in the form of a Solar Oven by Jan J Hofmann, Gabriele Klieber and Ulrich Zimmermann, essentially a low-tech box which reflects and magnifies the suns rays to allow for resource free cooking; and the 2018 Frankfurt Rent Referendum initiative which has petitioned the city authorities to ensure that all future public housing construction in the city is of affordable apartments, and to ensure rents remain affordable for low and medium earners.

And a project which underscores for us where one of the more obvious answers to the question of organising sufficient affordable housing can be found. Many of the Neues Frankfurt houses are now privately owned: if you want affordable housing, don't sell the stock you have. Which in most European nations is a case not so much of waiting until the horse has bolted before locking the door, as of removing the lock and actively encouraging the horse to bolt; current discussions in Frankfurt, or, for example, those in Berlin about "nationalising" the city's housing stock, being all a direct consequence of the sale/privatisation of public housing in previous decades, strategies invariably undertaken in that quaint belief that the free market can deliver affordable housing. A second answer for us, and as we discussed previously in context of the 1929 Congrès internationaux d’architecture moderne in Frankfurt, is to consider less what was achieved in Frankfurt and more how: Neues Frankfurt was financed through a tax on private property, a tax ring-fenced for the construction of affordable accommodation, and a tax that still rings with clear logic.

The final house of the Wie wohnen die Leute? Neues Frankfurt estate, the almost Bavarian sounding ZWOFADOLEI***, is populated by considerations on contemporary constructive developments in and of the housing: how the users have, as with their kitchens, adapted them to meet their new, contemporary, individual needs. Then as now the standardised nature of the housing causing a reflex rejection from many, but must standardised mean impersonal?

Amongst the projects considered under the title Das neue Umbauen - New Alteration - is Ich wohne! by Cäcilia Gernand, which poses several questions and then asks you to create a floor plan which meets the needs represented by your answers; and which in doing so reminds us of both the "Variables Wohnen" experimental high rise flats developed by Rudolf Horn and others in 1970s East Germany, and also the Elementa system developed by the West German Neues Heimat housing corporation, both of which allowed for flexible floor plans within standardised systems, and thus how such inter-War ideas were extended and developed post-War. And thereby leads to the associated question of where and why the development of such thinking stopped? And, and as discussed in context of Stiftung Bauhaus Dessau's 2018 Bauhus Lab The Art of Joining: Designing the Universal Connector, the potential role of new technologies in contemporary re-imaginings of such thinking.

Whereas most of the projects presented in context of Das neue Umbauen concern themselves with internal adaptations, as we noted in our post from New Housing, New People, walking around the estates one understands the scale and scope of external alterations undertaken; and while we, being as we are us, tended to focus on the more kitschy adornments, many of the adaptations, internal and external, are not only appropriate but necessary, respond to the evolved realities in which the houses exist today, the changing needs of their occupants.

Some occupants however cannot adapt their houses, standing as they are under historic building protection orders. A positive situation in terms of preserving the work of Ernst May et al?

Despite the kitsch we'd argue not, would argue as we often do that one shouldn't get too caught up in historic building protection legislation, for all where it stands in the way of enabling the meaningful use of buildings. Neues Frankfurt was realised with the aim of providing appropriate, affordable housing, it should be allowed to continue to provide just that. Including a, very grudging, right to kitsch.

Presenting a mix of artistic, documentary and interactive projects Wie wohnen die Leute? not only provides a platform for consideration, discourse and discussion on both the development of the Neues Frankfurt estates and the contemporary requirements and demands in context of urban housing and urban design, but also, and as with New Housing, New People, implores you to get out and explore the estates yourself, to transfer that which you've seen and read to the estates and then consider it anew.

But for all as an exhibition Wie wohnen die Leute? makes very clear that a housing estate, an urban conurbation, is a living organism, one that feeds itself less on that which its architects and planners supply it as on the interaction with those who populate it, that it continually and incessantly evolves and develops with the community that it houses, and as such allows for an understanding of housing provision which neatly echoes Balkrishna Doshi's opinion that, "form should not be finite but should be amorphous, so that the experience within is loose, meandering and multiple."

Which, as ever, isn't to say that Neues Frankfurt got everything right, it didn't, nor is it to hold it up as a best case example for urban planning, it isn't; but is to say that when considered in its social/cultural contexts rather than the architectural/design contexts in which it is normally considered, and that, arguably, optimally, in conjunction with other projects such as those realised, for example, inter-War in Vienna, Stockholm, Berlin or the post-War, again Ernst May influenced Neues Heimat programme, then Wie wohnen die Leute? implies that Neues Frankfurt has much to offer in helping us better approach answers to the specific housing and urban design problems of our own age.

And although in a very real sense a very Frankfurt specific exhibition, many, all?, of the discussions are directly applicable to wider, global, questions of the provision of contemporary housing, of the creation of meaningful, supportive and responsive urban spaces.

Just as was attempted in the 1920s and 1930s by the Neues Frankfurt estates.

Wie wohnen die Leute? runs at the Historisches Museum Frankfurt, Saalhof 1, 60311 Frankfurt am Main until Sunday October 13th.

* MEhrFAmilienhaus - Apartment block

** MEhrFAmilienhaus, AußenGANGtyp - Apartment block with external access stair

*** ZWeiFAmilienhaus mit DOppelLEItung - Semi-detached

Full details, including information on the accompanying fringe programme, can be found at https://historisches-museum-frankfurt.de