Whereas at Bauhaus Weimar and Dessau architecture was essentially a subject of theory and experimentation, elsewhere in inter-War Europe architecture was theory and practice, and that, occasionally, on a large scale. Such as the Neues Frankfurt project.

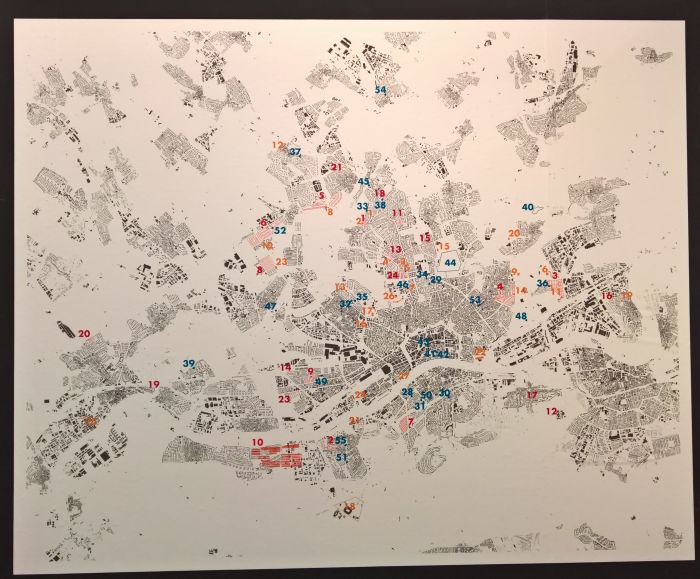

Instigated in 1925 by Frankfurt's then Mayor Ludwig Landmann and employing a team of some 148 architects, urban planners, garden designers, journalists et al, under the leadership of Ernst May and Martin Elsaesser, Neues Frankfurt realised between 1925 and 1933 some 12,000 new homes in Frankfurt; but for all indicated possible new forms of building, new forms of living, new forms of financing housing and new forms of urban planning. New forms that were not only responsive to the new political, social and economic realities of the 1920s, but utilised to that end advances in both process/materials technologies and also scientific understandings.

With the exhibition New Human, New Housing: Architecture of the New Frankfurt 1925–1933 the Deutsches Architekturmuseum Frankfurt reflect on the project, and into the future of urban planning and the provision of of housing in the city.

As an exhibition New Human, New Housing: Architecture of the New Frankfurt 1925–1933 opens with the background to the project, including brief discussions and considerations of and on the persons Ludwig Landmann, Ernst May and Martin Elsaesser, before moving on to present not only 10 from the 30+ housing estates realised in the project's short life, but also many of the public buildings created in course of the project, including, and amongst many others, the Market Hall, Waldstadion or the Gustav-Adolf church in Niederursel. In addition New Human, New Housing explores associated aspects such as electrification, the industrial construction methods practised, the Kleingarten, allotments, associated with the estates, and the Frankfurter Küche by Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky, arguably the best known result of the Neues Frankfurt programme, and as previously discussed in these pages, a work true to Schütte-Lihotzky's position that "the role of the architect is one of organisation. The house is the considered organisation of our ways of life". A position that that can also be used to describe Neues Frankfurt, and for all the reality that an evolving society with evolving habits and evolving demands requires evolving infrastructures; that the New Human needs New Housing which allow for a new organisation of their contemporary ways of life.

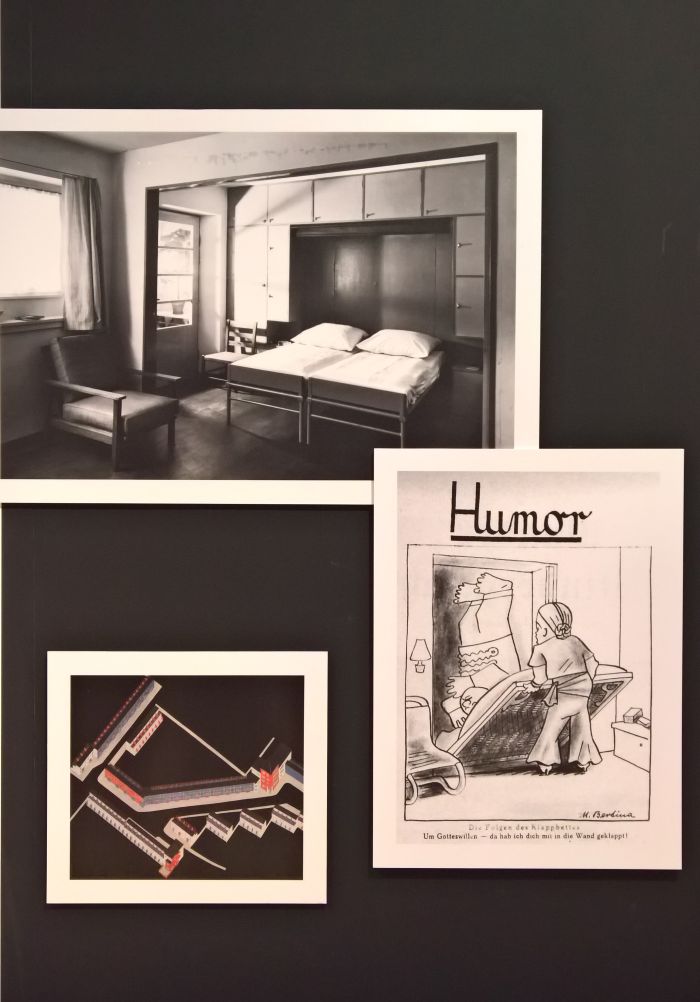

That not everyone at that period was fully enamoured by the nature of the changes proposed by May et al being reflected in a number of cartoons from the period poking fun at many of the new ideas; cartoons which when considered in context of those in Heath Robinson & K. R. G. Browne's 1936 book How to Live in a Flat indicate that doubting, laughing at, mocking modernism was every bit as international as the architecture itself.

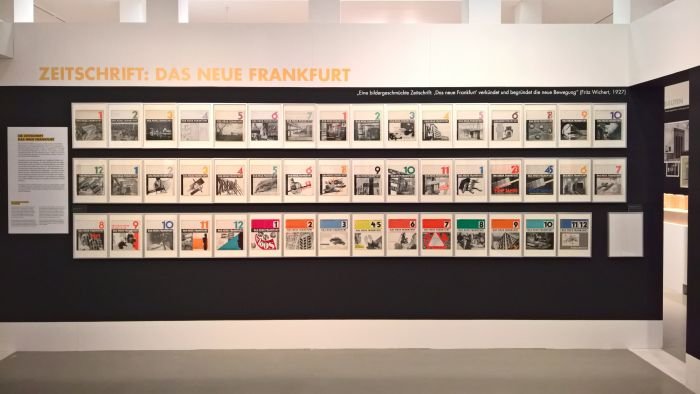

Beyond the architecture of Neues Frankfurt per se New Human, New Housing also takes brief diversions to visit themes as diverse as the 1929 Congrès internationaux d’architecture moderne, CIAM, conference in Frankfurt, the importance of Nietzsche in propagating the reformist ideas of the late 19th/early 20th century, and the Neue Frankfurt magazine that was produced to promote the project, the protagonists, their positions; and which is presented alongside the so-called Frankfurter Register, a supplement to the Neue Frankfurt magazine and which made suggestions/promotion for/of furniture, lighting, fixtures and fittings for the progressive, reformist, modernist home. Suggestions/promotion which in addition to the likes of PH lamps, Thonet chairs, Schwarzwald clocks from Junghans or Bauhaus wallpaper from Hannoversche Tapetenfabrik Gebr. Rasch & Co, are primarily of objects from manufactures based in Frankfurt and environs, including, for example, Fuld telephones, Kaiser Idell lamps, Ferdinand Kramer's cast-iron stove or the so-called Frankfurter Bed by Heerdt-Lingler and which folded into the wall, thus optimising space saving in the compact properties. And in presenting the Frankfurter Register, and thus underscoring the links between the building and product design of the period, New Human, New Housing links very nicely into Moderne am Main 1919-1933 at the Musuem Angewandte Kunst: the Musuem Angewandte Kunst have the objects, the Deutsches Architekturmuseum the buildings, and we all have a better understanding of inter-War Frankfurt, inter-War Hessen, inter-War design, inter-War architecture.

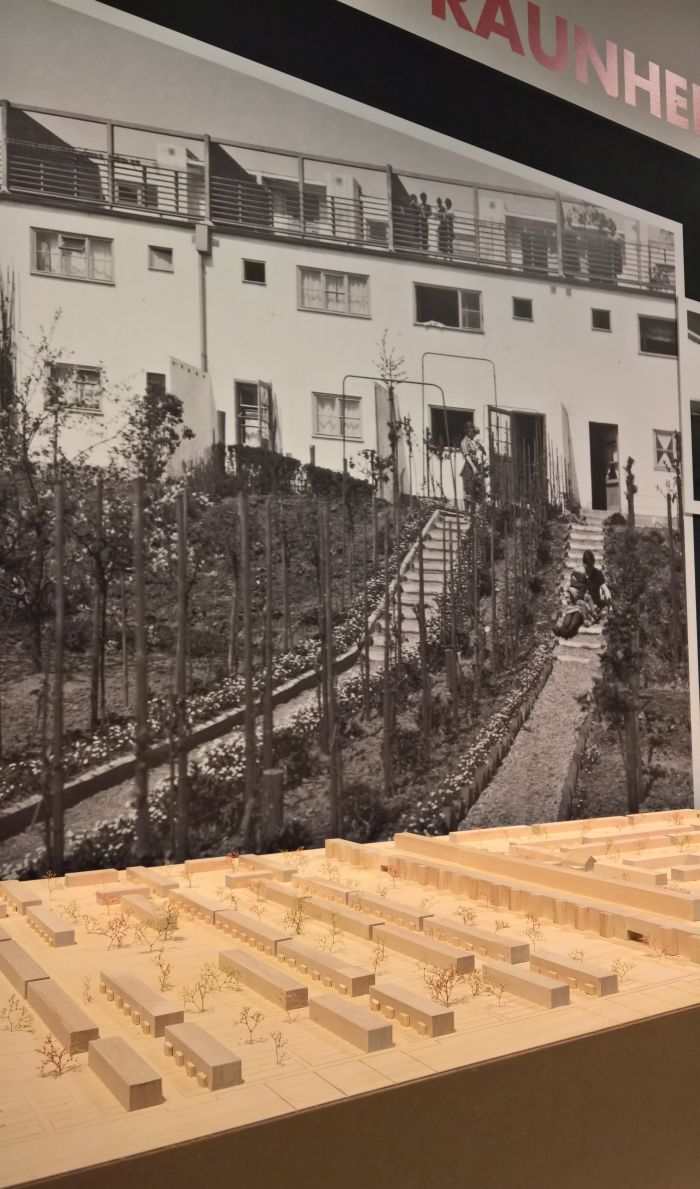

Presenting models, plans, sketches, photographs, videos, et al New Human, New Housing provides for an intelligently conceived and pleasing realised presentation which allows for an easy and accessible introduction to the subject without overpowering the visitor; is, we'd argue, more an exhibition for the, relative, newcomer to the subject rather than the, seasoned, expert, but then are the majority of us not in need of more education about inter-War society, architecture and design?

Pleasingly informative and entertaining as New Human, New Housing is, as an exhibition it still struggles somewhat under that perpetual burden of how does one present something of the scale of architecture, far less the scale of urban planning, in the confines of a museum?

With its intelligently pared down mix of models, documentation and short bilingual German/English texts New Human, New Housing makes a good argument for how such could be achieved, but, and as with Volksbedarf statt Luxusbedarf - Bernau and its Bauhaus at the Galerie Bernau, the better solution is to first view the exhibition, and then take yourself off to the various locations. Take yourself off into the architecture exhibition space that is Frankfurt. And where one can experience that which you have seen modelled, photographed and described. Or put another way, if Neues Frankfurt represents new ideas of architecture and urban planning in practice, then what better way to experience them than in vivo?

Not least because through such one can better understand and appreciate the project, for example, the scale of the buildings, the relations between the houses and the gardens, allotments and public spaces, or the scope of areas developed and range of typologies of housing realised. Yes since the war there have been changes, but the essence remains very much the same. And tangible.

For our part our attention was particularly caught by the regular provision of compact porches, something especially keenly, and intelligently, employed in the last phase of the Praunheim estate; and also by the realisation that no matter how reformist and progressive the intentions of the architect, a German will always, but always, find a way to drag it back into a previous age through an astutely swung Hammer of Kitsch.

Viewing the estates also leads you to understandings not covered by the exhibition, including, for example, that, developed as they were in the late 20's early 30s, none of the estates were designed for mass private car ownership; a fact which means there is more space for living, there being no necessity for wide streets and parking spaces, one can instead have communal garden areas. Which, yes, means today the streets are clogged with parked cars; but also poses the very obvious question, why rely on mass private car ownership? Isn't the better mobility friendly city that which doesn't clog its arteries and thoroughfares with private cars? But which instead encourages and supports mobility.

In addition, and as we oft note, viewing a city from an architecture or design perspective allows for a differentiated view, and for all allows you to visit parts of a city you never normally would; which in case of Frankfurt means quarters such as Römerstadt with its connection to the River Nidda and adjoining meadows, to the more urban Hellerhof by Mart Stam and where today new housing blocks of a completely disparate scale and character have arisen or Heimatsiedlung with its expanse of windows and public greens. And a visit which leaves, or at least should leave you, posing the question, how do the works from then hold up today?

A very good question, a very important question.....

......and one which should be answered, or at least should be approached, in the Historisches Museum Frankfurt's forthcoming exhibition Wie wohnen die Leute?, the final instalment of Frankfurt's triumvirate of Neues Frankfurt exhibitions in 2019.

A second question is posed by New Human, New Housing itself in its final chapter: what, a century or so later, can we learn from Neues Frankfurt?

The Deutsches Architekturmuseum will, more or less, provide it's answer in the forthcoming exhibition Homes for all – The New Frankfurt 2019 which will present the results of a competition organised by the museum and the Frankfurt city council for new contemporary, affordable housing.

From our part, aside from the advantages of a car free city, and our previous argument that the financial model of Neues Frankfurt deserves as much reflection as that which was created, one could, and we would, argue that some lessons can and could be found in the exhibition Die Neue Heimat (1950–1982). A Social Democratic Utopia and Its Buildings at the Architekturmuseum der TU München, in which one can follow, or at least begin to follow, Ernst May's post-War directions and thereby how his understandings of social, communal, urban architecture and planning, how that which he learned from Neues Frankfurt, developed in context of the new post-War realities, if, as noted, those lessons still need to be soberly considered. Further, arguably more practical, lessons will (hopefully) also become clear in Wie wohnen die Leute?

However in many regards the most important thing one learns is that one can and should always learn from history. Realities change, often fundamentally, but parallels invariably exist, parallels which don't necessarily allow for exactly the same solution, but which can help point in new directions, and help you understand that those new directions might be radical, might involve moving away from established wisdom; and that cities need to evolve in order to remain relevant to their residents, and that role of the architect, urban planner and designer is to interpret the needs of evolving cities, the evolving social, political, economic, technical realities, into structures, systems and processes that facilitate that. Or as Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky opined, architecture should be a “service to people”, and that it "can never be an end in itself, never be just l’art pour l’art“

Which isn't to say that the Neues Frankfurt team got everything right, but is to say they set enough theory into practice to allow future generations to make better informed decisions about their own contemporary housing.

New Human, New Housing: Architecture of the New Frankfurt 1925–1933 runs at the Deutsches Architekturmuseum, Schaumainkai 43, 60596 Frankfurt am Main until Sunday August 18th. Full details, including information on the accompanying fringe programme, can be found at www.dam-online.de