The Chinese government warning pro-democracy demonstrators to end their street protests. Central Americans risking their lives, and dodging border guards and fences, to cross into America in search of the, much vaunted, American Dream. A dogmatic right wing English Conservative government showing their contempt for the people of Scotland.

Thankfully, the world has moved on since 1989......

..........1989 was however also a year of more positive political developments: the Berlin Wall fell, indeed the whole Iron Curtain was drawn; in South America the dictatorships of Augusto Pinochet in Chile and Alfredo Stroessner in Paraguay ended at the ballot box; while F.W. de Klerk's election as South African President ushered in the decisive end-phase of Apartheid, and led directly to Nelson Mandela's release from prison in February 1990, after serving 27 years for having done no more than expect his skin colour to have no bearing on his freedoms and liberties.

A year of monumental moments in not only the histories of the world, but for all the biographies, the daily lives, of millions of men, women, children and the yet unborn. And a year of monumental moments that also stand representative for, as a snapshot of, wider changes in society as the 1980s ceded to the 1990s. A snapshot enlarged and explored in the National Museum Stockholm's exhibition 1989 - Culture and Politics.

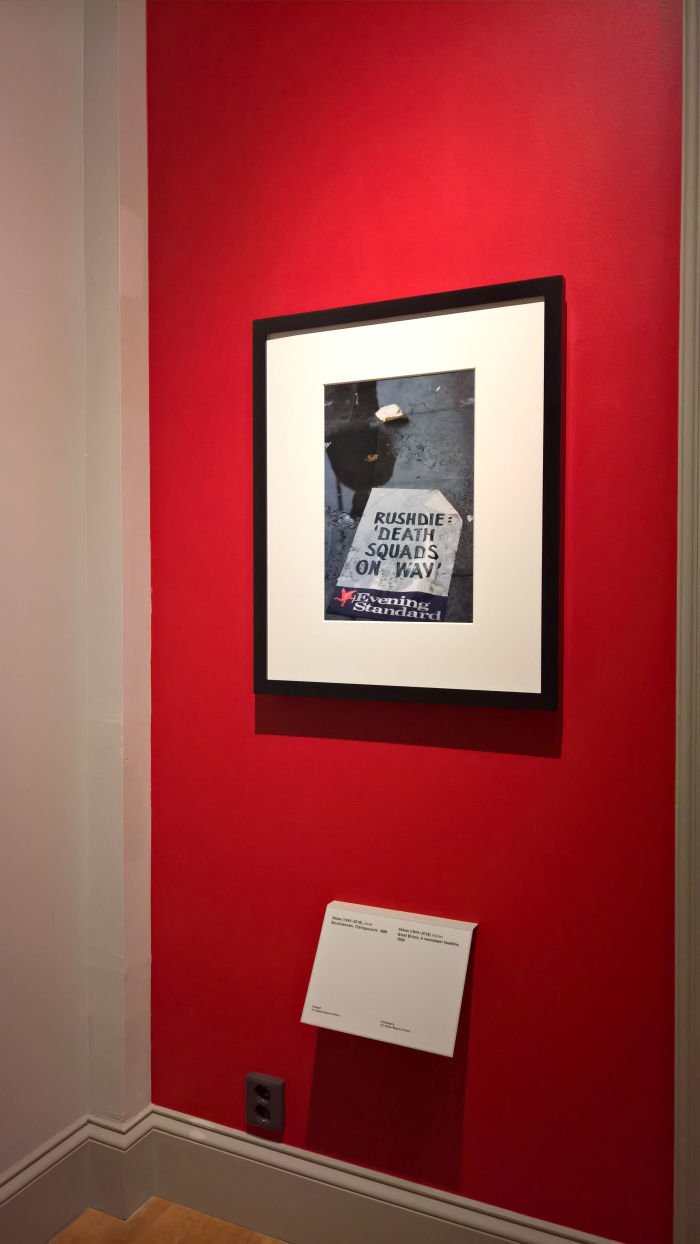

Despite the very equivocal title, the exhibition design is very much 1989 Culture. 1989 Politics. The two forming distinct components of the whole, and opening with the latter via brief introductions to some of the key international theatres of 1989: Berlin, Beijing, Prague, Bucharest, South Africa, Central America and the, then, USSR. Introductions led, as so often in politics, by posters and graphic art, but which for the larger part relies on eye-witness photography, photo-journalism: on the one hand documentary works of everyday life including Carl de Keyser's 1988/89 photos in the contemporary Russia and Uzbekistan, Boris Mikhailov's images of Ukrainians relaxing in a (more or less guaranteed) toxic salt lake, or a selection of David Goldblatt's images of his native South Africa. And on the other hand by front line photo-journalism from the protests, unrest and celebrations. Including New Years Eve 89/90 in a freshly wallless Berlin. A statement in its own right. And thus a presentation format which not only succinctly and comprehensibly helps explain (some of) the events of 1989, a picture painting as it does a thousand words, but for all which, certainly through the front line works, underscores the importance of photo-journalism to our understanding of the world, being as it was through, for example, and amongst many others, Jean-Claude Coutausse and Tomki Nĕmec's photos from Prague, Susan Meiselas' from the Mexican/USA border, or Stuart Franklin's from the protests, and for all their suppression, in Tiananmen Square, that the wider world received an impression of what was happening. Ensured that it didn't happen in isolation. Something perhaps most dramatically illustrated by Franklin's The Tank Man: standing tall, standing alone, demanding democracy from tanks with nothing more than his human flesh and bones. An act of defiance which remains without parallel. And instructive for the fact that the man himself remains anonymous. History records not his name but his act. How many politicians would act so selflessly if their name wasn't to be associated for all posterity with their deed?

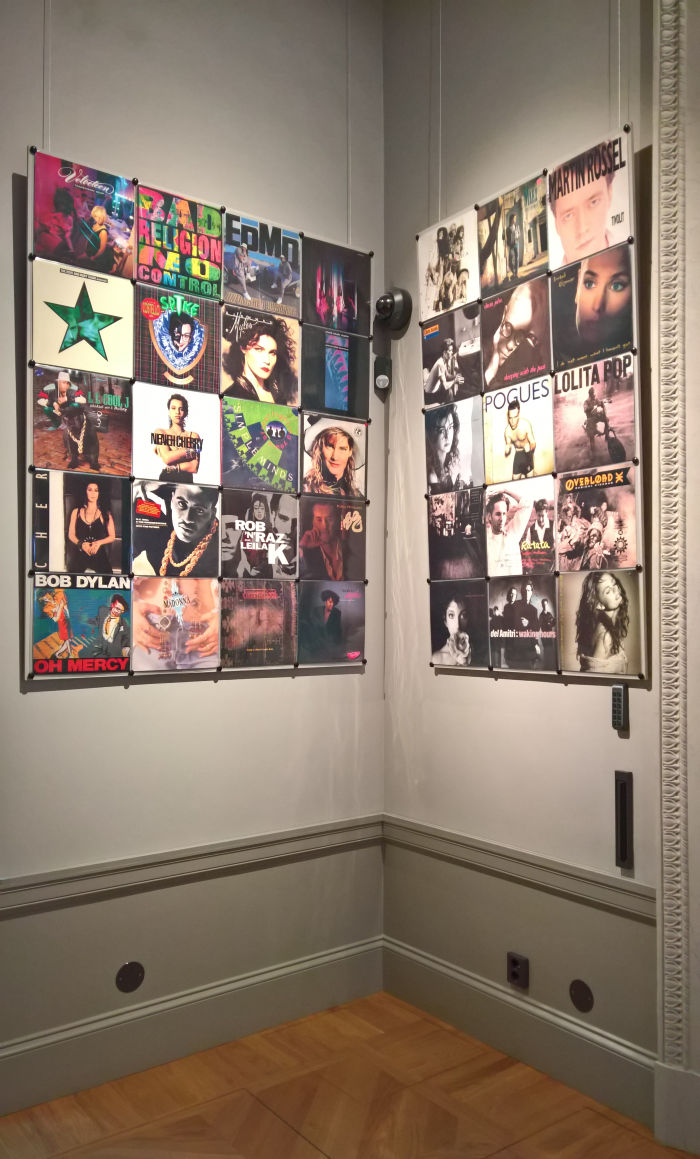

Having set the 1989 political scene the exhibition moves on to 1989 Culture, starting with music and a selection of works released in 1989, a selection presented as record sleeves and videos, a selection every bit as eclectic as one would wish to represent the confusions of the period, if a selection with one glaring omission: you cannot, simply cannot, discuss 1989, Germany, Walls, and not include The Hoff. You can't. The Scorpions and their Wind of Change may be popularly understood as the Wende Hymn, but that was 1990. And is clearly set in Moscow. In 1989 however David Hasselhoff went Looking for Freedom, and found a success in Germany unparalleled to that he enjoyed anywhere else. And which he stills enjoys today. And while yes its absence from the exhibition does save you the earworm, its presence would allow you to reflect on the lyrics, which no-one ever does. For while he went looking for freedom, he didn't find it, indeed, as he tells us, "still the search goes on". Thirty years later. We'd argue because he's looking in the wrong place. Freedom is, yes, unquestionably, physical and political, but freedom begins within, and we don't believe he's there, believe internally he's still locked in by memories, arguably incomplete, biased, deceptive, memories, and until he learns to let them go, to move on, to align his world view with world realities rather than a reflection of the world past, freedom will always remain an elusive dream. Freedom isn't something one receives, but which one takes, isn't something one looks for, but which one finds. Then there's the fact he appears to be seeking freedom in exactly that from which he's fleeing. ??? A very poor song, but as a metaphor for contemporary eastern Germany. Stunning. And one they picked themselves in 1989. And apologies if we've now given you an earworm.

From the music of 1989 the exhibition moves on to explore further culture expressions, expressions which can most easily, lazily, be sub-divided into art and design: the latter being largely about Postmodernism, about design which questions the dictum of form follows function, questions the value systems in our objects of daily use, considers objects linguistically as much as physically, but also concerns itself with late 1980s understandings of material, aesthetics and the function of furniture within a space, and as expressed by works such as Philippe Starck's W.W. Stool, Marc Newson's Embryo Chair for Cappellini or Ron Arad's Little Heavy chair. It is however not all provocative, in your face challenges to established conventions and wisdom, there is also some pared-down simplicity, inklings that the abstraction of Postmodernism was ceding to more subtle, quieter, forms of expression, including the Ply-chair and a chaise-longue from Jasper Morrison's 1989 Milan installation Some New Items for the Home, Part II. The Ply-chair, appropriately enough, having been developed and realised by Morrison in 1988 in West Berlin. Where the decade after 1989 would be anything but subtle and quiet.

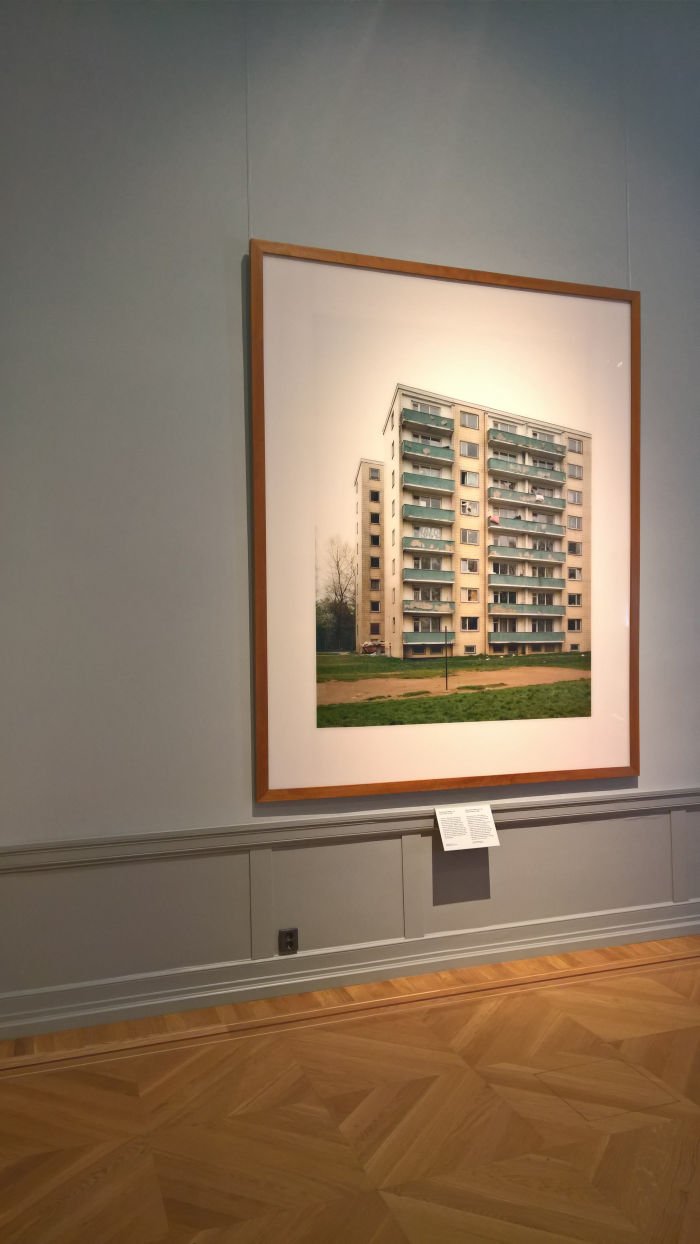

The art of 1989, and again bisecting for simplicity, is represented on the one hand by photography, including works by the likes of, and amongst many others, Alfredo Jaar, Tseng Kwong Chi or Thomas Ruff whose image of a Düsseldorf high rise block of flats reminds us that it wasn't just the east of Germany that needed renovating post-1989. And a collection of photography which despite being freer is often every bit as documentary as the photo-journalism in 1989 Politics, and which at times blur the borders between the two. In a provocative artistic sense one understands, and not the fake news stylee that is so popular today, which makes such a mockery of photo-journalism, scraping, as it mocks, at the roots of democracy.

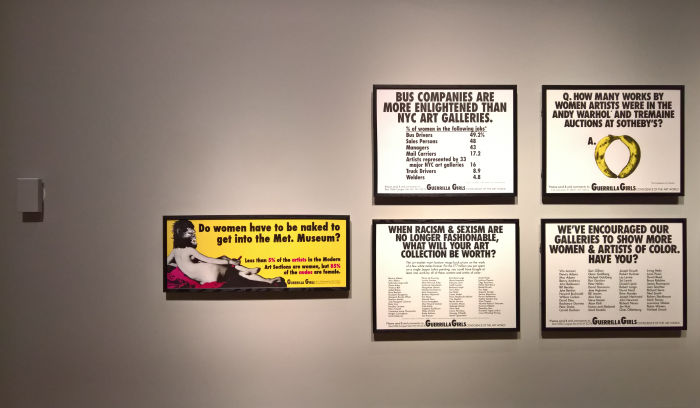

And on the other hand, non-photographic art works including Ignorance = Fear / Silence = Death by Keith Haring, an AIDS awareness piece, a work which reminds us all that 1989 was the year AIDS came to town, and thus reminds not only of the consequences it had/has, but that one should never forget medical history when exploring the continuum of human existence; and several works dealing with questions of gender equality and women's rights, including, for example, a campaign by the Guerrilla Girls collective highlighting the predominance of (white) male artists in art museum collections/exhibitions/by extrapolation in the popular understanding of art, and which much like the Kunstgewerbemuseum Dresden's 2018/2019 exhibition Against Invisibility, underscores that the popular view of not only contemporary culture but of the historic development of culture, is and are skewed by the dominance of white male creatives in those places where art and design are popularly consumed, while with her work/manifesto Untitled (Your Body is a Battleground) Barbara Kruger tells 1989 America to "Support legal abortion, birth control and women's rights". A poster that could be printed tomorrow and have lost nothing on contemporaneousness. If arguably a call that today would be more widely understood and attract a larger, broader support. But the fact it needs to be called remaining just as deplorable.

Thoughts which make very clear that although very much an exhibition about 1989, viewing 1989 - Culture and Politics is also to view the hypothetical 2049 exhibition: 2019 - Culture and Politics.

And to ask, how far have we actually moved since 1989? And how will 2019 - Culture and Politics reflect on us?

In terms of the first, Not far. Certainly politically. This isn't the time nor place for discussions on the contemporary political realities in Europe, China, Russia, South Africa, America, the Mexican/USA border, et al, and how they have developed since 1989, although we wish it were; however, what 1989 - Culture and Politics does make very clear is that while thirty years is a long time, it is also barely a generation and real, meaningful, sustainable, change, needs ever new generations to interpret the past into the future, to apply their experiences and understandings. And without that the political situation can't change. Plus one must never forget that progress is rarely a straight line journey, but rather one that involves Brexit, nationalism, Trump detours, getting lost, going the wrong way, going backwards, but these episodes rarely derail progress, simply delay it, and when one looks back from far enough in the future one invariably sees forward movement. And so looking back in 2049 on 1989 one will be in a better place to answer that question.

And how will that 2049 exhibition reflect on us?

For us the principle reflection will be in terms of how we've raised a child of 1989: The World Wide Web. The courses along which the various political events of 1989 have developed are in many, not all, but many, regards responses to inherent features, have historical components, are related to the way the myriad elements are linked and inter-related. Conceptually proposed by Tim Berners-Lee in March 1989, the World Wide Web was new. Had no history. Was in many regards the Aristotelian blank sheet. It was up to us to nurture it, cultivate it, guide it as it grew and developed. And boy did we mess up!!! One of the most powerful tools ever placed in the hands of mankind, a possibility to link distant societies in real time, to develop global communities, to freely spread information at a rate and in dimensions previously unimaginable, and to thereby empower the individual and strengthen democracy. And we use it to steal, to cheat, to fake, to abuse, to boast, to pervert, to misinform, to bully, to manipulate. It's as if upon being given the plough people had started using it to hack at one another, rather than furrow the fields and grow the crops necessary for the sustenance of mankind. Imagine where our culture and our politics could have been in 2019. Consider the opportunities 1989 gave us. Virtually and physically.

Our utter failure to properly contend with and understand the technological advances of the late 1980s and early 1990s being further underscored in the exhibition by a Philips AP 6112 mobile phone, 20 cms long and weighing in at some 500 grams, and an Atari Portfolio palmtop PC, essentially the beginning of mobile computation. The way in which we've contrived to turn these two very useful, liberating, ideas into a form of prison we carry around with us, and to which we've developed a collective Stockholm Syndrome relationship and corresponding refusal to be separated from, being a truly tragic indictment of contemporary society. And politics. Politicians have not only been found wanting in their understanding of digital technology, but wanton in their misuse of such.

Much more positive, if hopefully every bit as critical, would, should?, be 2019 - Culture and Politics' considerations on a subject that although present in 1989 - Culture and Politics is and was in 1989 nowhere nearly as central as it should have been: the environment. In the late 1980s the dangers and problems were known, for example, The Club of Rome's The Limits of Growth had been published in 1972, but the dangers and problems were generally ignored. Yes, in 1987 the Montreal Protocol banning CFC gasses was ratified, but arguably only because the hole in the ozone layer had become way toooo big to ignore, and industry had developed new gases. But as a rule environmental activists were a fringe group of harmless freaks, and invariably vegetarians to boot, late-era Hippies who hadn't realised the world had moved on: politicians, bankers and industry knew best. And so since 1989 we've pushed the environment ever harder and ever further. And now it broked. If we'd stopped putting plastics in the oceans in 1989, we wouldn't have to fish them out in 2019. And so a little late but today there is arguably no subject where popular culture is more active than the environment, no subject in which so much of the spirit of transformation, activism and resistance that is visible and audible in many of the 1989 works is reflected, no subject where popular culture is so directly influencing politics. And popular cultural activity in which Sweden, specifically Stockholm, is currently playing a central role.

Whereas Greta Thunberg's hand-painted Skolstrejk för klimatet sign will, must, feature prominently in 2019 - Culture and Politics, Sweden isn't at the heart of 1989 - Culture and Politics. Certainly not 1989 Politics: whereas the 1980s were a very important decade for Swedish politics, for all the ending in the late 1970s of a 40 year Social Democrat monopoly on government making the 1980s a decade of genuine, fundamental, political and economic upheaval and realignment in Sweden, and that against the backdrop of growing global neoliberalism, the reverberations were largely domestic.

Similarly, whereas in 1986 the aptly, prophetically?, named Europe may have formally initiated The Final Countdown for 1989, aside from singular exceptions such as Roxette, Swedish creatives rarely enjoyed a mass popular appreciation on the international stage; on the domestic stage however 1989 was every bit as rich, confrontational and progressive as that found elsewhere. Something reflected in the form of an exhibition-within-an-exhibition that runs through 1989 - Culture and Politics and which we, and we alone, are calling, 1989 - Culture and Politics and Sweden. An exhibition which includes furniture such as the Aluminium Easy Chair by Mats Theselius or Jonas Bohlin's Triptyk table, both for Källemo and thus reminders, as noted from the exhibition 1980s – A new era in furniture design at The Museum of Furniture Studies Stockholm, that the 1980s was a period of radical change in the Swedish furniture landscape, and a period that continues to influence the contemporary Swedish furniture industry; or photography by the likes of Ingrid Orfali, Lars Tunbjörk or Annica Karlsson-Rixon whose Turister [Tourists] collection not only challenges cultural and aesthetic conventions but predicts the rise of the selfie. The difference being her works are critical social reflections not self-aggrandising self-reflections. Of all generations to be given portable digital technology, why us? Why not one who would be thankful and appreciative?

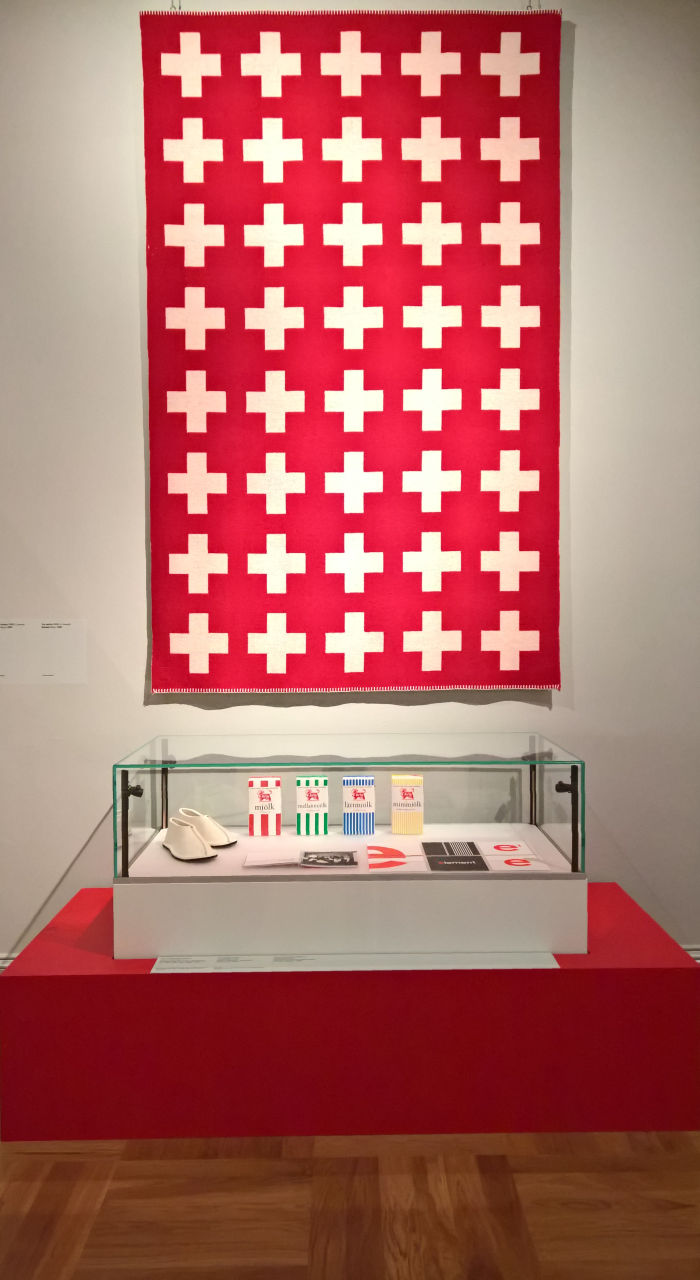

In addition one finds glass works by Ingegard Raman, clothing by Anna Holtblad, textiles by Pia Wallén, milk packaging by Tom Hedqvist and music by, and amongst many others, Jerry Williams, Thåström, Traste Lindéns Kvintett and, invariably, Roxette. And thus a presentation which, one imagines, will allow Swedes many a "remember that", "remember those days" moment, for all the reminder that in 1989 the Swedish men's table tennis team won the World Championship, who knew that!! But which also allows non-Swedes a deeper look into a period of Swedish cultural evolution than is normally afforded, and to compare and contrast not only what was happening in Sweden with what was happening elsewhere, but to reflect on the Swedish influence on creativity since 1989. And thus approach a more realistic understanding of Swedish art and design since 1989.

As an exhibition 1989 - Culture and Politics is very much wider than it is deep, the sheer scale of the subject matter enforcing such, and also limiting just how wide it can be. And it could be a lot wider. For all 1989 Culture which is very much 1989 European/American Cultural; save a couple of works, South Africa, Central America, Southern America, China, former USSR et al are absent and therefore the political/cultural interplay is very much a European/American political/cultural interplay. Which isn't a complaint. While a global perspective would have been much more welcome, it would require both space the museum simply don't have and time most viewers wouldn't be prepared to spare. And so the restriction is logical; it is however important visitors understand that in other regions of the world the helix was turning and leading to interplays with a local dialect all of their own. This isn't, can't be, the full story of 1989. Culturally or politically.

And while we're unhelpfully, unnecessarily, noting what isn't on show, arguably the biggest omission of all is the greatest gift 1989 gave global society: December 17th 1989 seeing the first, pilot, episode of The Simpsons. And since when, and after an absence of far too many thousand years, the wisdom of Homeric poetry has once again rung throughout the nations. We're not all listening, but it's there......

And The Hoff. It needs The Hoff. No honest!

A well paced exhibition which makes intelligent use of the anti-chambers and alcoves of Friedrich August Stüler's neo-renaissance building to house, and through spatial separation, highlight its numerous chapters, 1989 - Culture and Politics provides for an entertaining and informative tour through the cultural expressions of the period without getting too bogged down in the political arguments of the period, not that they are not there, they're everywhere; much more, rather than underscoring them at every station, which would be monotonous and tiresome, the exhibition makes very clear on the one hand that politics is politics, culture is culture, and on the other that despite the clear distinction that must be made between the two, politics and culture move in tandem, or perhaps better put, entwined, that evolving political landscapes feed into the cultural consciousness, whose heterogeneous evolutions then feed back into the political, which sends impulses to the cultural, to the political, to the cultural, to the political, to the cultural, on, and on, and on, and..... inalienably and inextricably linked

Or put another way, that which is displayed, both in 1989 Politics and 1989 Culture may have been realised in (+/-) 1989, but was a consequence of developments that had been brewing for sometime, the political developments influencing the cultural and vice versa as they brewed, that 1989 didn't arise spontaneously, didn't come from out of nowhere, and certainly didn't end there. 1989 continues to influence and inform contemporary culture and politics. So much so that sometimes one could be forgiven for mistaking 2019 for 1989.

1989 - Culture and Politics runs at the National Museum, Södra Blasieholmshamnen 2, 111 48 Stockholm until Sunday January 12th

And for all in or near Stockholm this autumn/winter, from October 17th the National Museum is also showing Hella Jongerius – Breathing Colour

Full details can be found at www.nationalmuseum.se