Looking back from the safety of 2019 it can be all too easy to assume that Bauhaus was a popularly received and much celebrated institution.

❌

From its very earliest days, even before the first students had arrived in Weimar, the institution met with tenacious criticism and steadfast resistance; and arguably nowhere more so than in Weimar.

With the exhibition Mathilde von Freytag-Loringhoven. Painter, Author, Animal Psychologist and Bauhaus Critic the Stadtmuseum Weimar introduce one of the institution's most tenacious and steadfast opponents; and in doing so allows not only for considerations on some of Bauhaus's lesser discussed (hi)story, but also for reflections on the political, social and cultural realities of 1920's Germany......

Born in Copenhagen on October 30th 1860 as the fourth of six children to the diplomat Karl Gottlob von Freytag-Loringhoven and his wife Mathilde Luise Kalkmann, and as a scion of one of Westfalen's oldest noble houses, Mathilde von Freytag-Loringhoven spent the majority of her childhood in (the then) Danzig, before, in wake of her father's 1879 retirement, the family moved to Weimar, and where, aside from regular, oft prolonged, travels throughout Europe, Mathilde von Freytag-Loringhoven remained until her death in 1941. And thus an association with Weimar that covers a period of extreme, and fundamental, changes in not only the city's position and fortune, but also those of the wider "German" state.

The story of Mathilde von Freytag-Loringhoven. Painter, Author, Animal Psychologist and Bauhaus Critic begins however in Danzig, or at least the chapter Mathilde von Freytag-Loringhoven - Painter does, and where the young Mathilde von Freytag-Loringhoven undertook art lessons with Wilhelm August Stryowsk, a teacher at the city's art college and co-founder of the contemporary Nationalmuseum Danizig. And awakening a passion for painting which continued in Weimar through instruction with the likes of Leopold Graf von Kalckreuth, Max Thedy and Karl Buchholz: all artists associated with Weimar's Großherzoglich-Sächsische Kunstschule, and where in 1880 Mathilde von Freytag-Loringhoven's paintings were first exhibited. The first of numerous exhibitions, both in Weimar and across Europe, in which her works featured during the course of the late 19th/early 20th centuries.

And in 2019. By far the largest focus of the Stadtmuseum's exhibition is paintings by Mathilde von Freytag-Loringhoven, for all her works depicting the forests and countryside of Thüringen, works very much in the so-called Weimarer Malerschule tradition, a form of open air landscape painting heavily influenced by the French Barbizon school and which was developed and propagated at the Großherzoglich-Sächsische Kunstschule. And a Realistic understanding of art also demonstrated in the many etchings and water colours by Mathilde von Freytag-Loringhoven on display. If a Realism with a regular breath and mist of the Romantic.

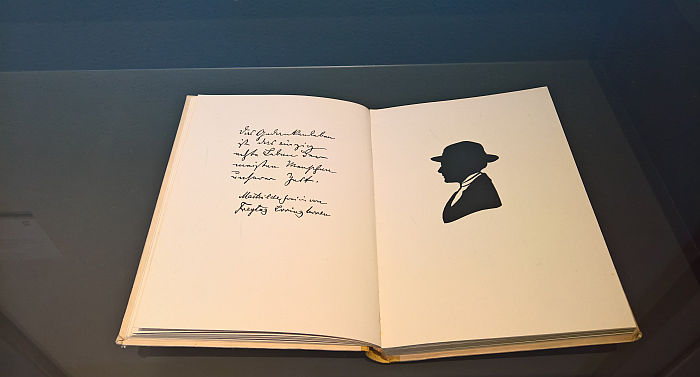

Mathilde von Freytag-Loringhoven - Author is the story of Mathilde von Freytag-Loringhoven as a playwright and novelist: the former with barely notable success, the latter through the publication of two novels under the pseudonym Hildegard Thildner, Virgine in 1896 and Rudolf Valdier in 1908; whereby interesting is both that although choosing a pseudonym she didn't choose a male one, but remained confidently, defiantly?, a female author in a very male world, and for all the subject matter of Virgine. We admittedly haven't read it, the only copy we know of is in a vitrine in Weimar Stadtmuseum; however, according to the exhibition curators Virgine is an educated, cultured, artistic female who although taking responsibility for her own fate is destined to remain an unfulfilled, unmarried, gentlewoman, and very aware of, but not defeated by, the fact: and thus, arguably, a biographic central female character. Mathilde von Freytag-Loringhoven - Author is also the story of Mathilde von Freytag-Loringhoven - Bibliophile who together with her sister Maria possessed an extensive library, including much in the French that was very much en vogue amongst the 19th century nobility, and of Mathilde von Freytag-Loringhoven - Actress, including note of her participation in a 1929 amateur dramatics society production of Shakespeare's A Midsummer Night's Dream, in which she played Bottom. And thus, and as with most all females associated with Bauhaus Weimar, Mathilde von Freytag-Loringhoven was also fated to be a weaver.

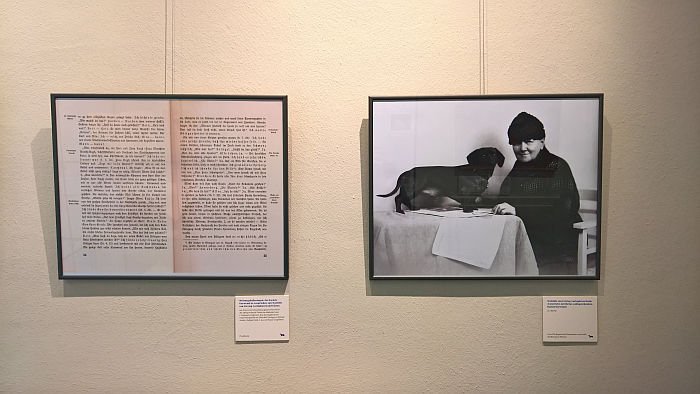

Mathilde von Freytag-Loringhoven - Animal Psychologist is, in many regards, the story of not one, but two, talking dogs..... no .....stop..... Isolde and Kurwenal are subjects for another day, really need to be considered alone. Really, really do. Even if their Wagnerian names provide a further clue as to Mathilde von Freytag-Loringhoven's cultural predilections; however, although a part of the exhibition that is central to the Mathilde von Freytag-Loringhoven biography, arguably that part of the Mathilde von Freytag-Loringhoven biography that is most popularly known, is that part which has the least connections with Mathilde von Freytag-Loringhoven - Bauhaus Critic

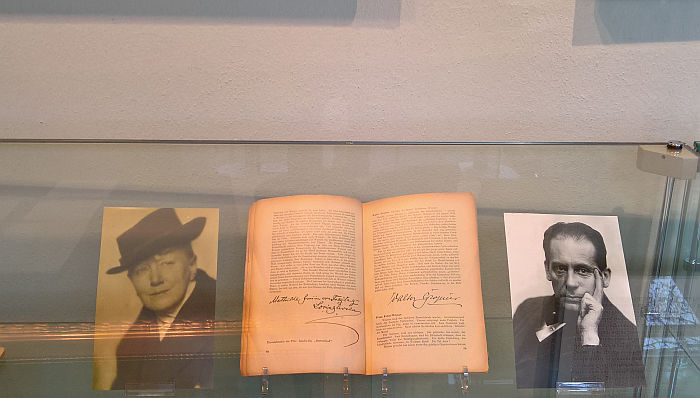

Not that Mathilde von Freytag-Loringhoven. Painter, Author, Animal Psychologist and Bauhaus Critic is an exhibition about Mathilde von Freytag-Loringhoven's criticism of Bauhaus. It isn't. Within the exhibition itself her criticism of Bauhaus is only fleeting touched upon, the discussion on her criticism of Bauhaus being one largely undertaken in the exhibition catalogue1; the exhibition itself is much more about approaching an understanding of where that criticism came from and which in doing so allows one to better approach a better understanding of the Weimar in which Bauhaus opened, or as Walter Gropius wrote to his colleague Adolf Behne on May 22nd 1919, and thus less than two months after his appointment as Bauhaus Director, "Here a wasps' nest has already awoken from its slumber and begins its pricking and stinging against me. There will be a hard fight ahead....."2, before noting in October 1919 to art critic and journalist Max Osborn, "My Bauhaus is slowly hatching from its egg, but the difficulties arising from the fossilised state of the Weimar public are of grotesque proportions", such fossils being for all "Eigentlich längst verstorbene Künstler oder solche, die es nie waren", "To all intents and purposes long-dead artists, or those who never were"3

And while not exclusively a reference to, the then 59 year old, Mathilde von Freytag-Loringhoven. She was unquestionably included in Gropius's fossilarium.

Understanding why involves firstly undertaking a deeper palaeontological study of Weimar.

As the residence city of the Sachsen-Weimar line of the Wettiner royal dynasty, Weimar established itself as an important, monarchical, political and military centre in the middle of the 16th century, and in the course of the 18th century achieved an ever increasing cultural relevance, not least through the presence in the city of the likes of Schiller, Herder, Wieland and for all Goethe; a cultural tradition continued in the 19th century with not only the founding in 1860 of the aforementioned Großherzoglich-Sächsische Kunstschule but the the appointment in 1843 of Franz Liszt as Conductor of the Weimar Hofkapelle, and who, lest we forget, during his Weimar years played a major role in establishing the reputation of Richard Wagner. Before in the early 20th century the focus turned once more to the monarchical, political and military: the Great War of 1914 to 1918, the defeat of Germany and thus its decline, collapse, as an international power, the abdication of Kaiser Wilhelm II and the declaration of the Republic in 1918, with the consequences that had for the House of Sachsen-Weimar and their followers, and the subsequent founding of the new parliamentary democracy in 1919. In Weimar.

Founded. 1919. In Weimar. Ring any bells?

Or put another way, socially, economically and politically Weimar in 1919 was no longer the Weimar Mathilde von Freytag-Loringhoven had moved to in 1879 and had understood, as a privileged member of the petite noblesse, throughout her entire adult life.

And Bauhaus, and the wider Modernist currents, with their challenges to existing understandings of creative expression, were now threatening Weimar's cultural tradition.

Not on Mathilde von Freytag-Loringhoven's watch!

Long as the exhibition title is, it should really be longer, should, in order to more comprehensively explain the relevance of Mathilde von Freytag-Loringhoven to the (hi)story of the period be titled Mathilde von Freytag-Loringhoven. Painter, Author, Animal Psychologist, Journalist, Politician, Neighbour and Bauhaus Critic.

Mathilde von Freytag-Loringhoven - Journalist being the story of how in 1913 she became the culture correspondent for the Weimar based newspaper Allgemeinen Thüringischen Landeszeiting Deutschland, as the exibition notes, a rare example of an early 20th century female journalist and even rarer example of an early 20th century female culture correspondent, and a position which gave her a platform from which to criticise not only Bauhaus and Modernist, Constructivist, Expressionist art in general, but the wider changes in Weimarian cultural life of the period: 1918 seeing the appointment of Wilhelm Köhler as Director of the Weimar Art Collection and 1919 of Ernst Hardt as intendant of the Weimarer Hoftheater, the contemporary Deutsche Nationaltheater, both men of an openly Modernist leaning, and both proactive supporters of Gropius and his Bauhaus. If Goethe, Schiller, Wiedland and Herder represented the Viergestirn of Weimarer Klassik, Gropius, Köhler and Hardt can be seen as a Dreigestirn of Weimarer Moderne. And Mathilde von Freytag-Loringhoven was keen to protect the tradition of the quartet from the intentions of the trio.

Mathilde von Freytag-Loringhoven - Politician is the story of how in 1919, the first year in which not only female's were allowed to vote in Germany but to stand as candidates, Mathilde von Freytag-Loringhoven was elected to Weimar City Council, and thus not only saw her become one of the first female politicians in Germany, but allowed her a, more or less, direct say in the state's official relationships with Bauhaus. Yes, the Thüringen Parliament in Erfurt was formally responsible for Bauhaus, but Weimar City Council not without its means and influence. Not least in terms of shaping public opinion in Weimar. Something a well-known, long established Weimar social and cultural figure such as a Mathilde von Freytag-Loringhoven was well placed to do. Particularly as she was also a local newspaper's culture correspondent.

Mathilde von Freytag-Loringhoven - Neighbour. Since 1882 the Freytag-Loringhoven family home had stood in Weimar's Marienstrasse and, as fate would deliciously, if somewhat mischievously, have it, directly next door to firstly the Großherzoglich-Sächsische Kunstschule, subsequently Henry van de Velde's Kunstgewerbeschule to whom the family lost, at the behest of Weimar City Council, half their garden, and an institution with whom Mathilde von Freytag-Loringhoven had a, at best, fractious relationship, not least on account of the missing garden half, and from 1919: Bauhaus. From her vantage point with its unobstructed view of the Bauhaus campus, Mathilde von Freytag-Loringhoven could observe the daily comings, goings and carryings on at the school; comings, goings and carryings on that, one presumes, weren't in a fashion keeping with those of the salons and receptions of late 19th century, pre-War, pre-Republic Weimar. Or at least not so openly. And a close proximity to the institution, its staff, pupils and their Avant-garde, Expressionist, Constructivist, Dadaistic, Esoteric ways that, one imagines and presumes, only served to harden her opposition to the institute.

If Mathilde von Freytag-Loringhoven. Painter, Author, Animal Psychologist helps explain why Mathilde von Freytag-Loringhoven was a critic of Bauhaus, explains her deep rooting in the Weimar of yore; Mathilde von Freytag-Loringhoven. Journalist, Politician, Neighbour helps explain how Mathilde von Freytag-Loringhoven became one of the leading figures in the pricking, stinging, difficulties and fights Bauhaus endured. Pricking, stinging, difficulties and fights which quickly developed into the so-called Bauhausstreit, Bauhaus Dispute.

Beginning, in essence, with the confirmation that the former Großherzoglich-Sächsische Kunstschule, since 1910 the Staatliche Hochschule für bildende Kunst, and the Kunsetgwerbeschule would merge to form a new institute under Gropius's leadership, the Bauhausstreit escalated through 1919 and 1920 via ever more bitter and ferocious attacks from the ever deeper entrenched antagonists, including amongst the various factions within Bauhaus, for all between the more traditionally inclined artists and their more abstract, futuristic colleagues, and which (more or less) ended in April 1921 with the (re-)establishment of the Staatliche Hochschule für bildende Kunst: a move which meant that from April 1921 onwards Walter Gropius was no longer responsible for art education in Weimar. And thus just two years after Weimar's art and applied arts schools had merged, they separated. Kunst und Handwerk eine neue Einheit - Art and Craft a new Unity - as Gropius formulated the start of Bauhaus in 1919, was in 1921 no more.

And a separation that one can understand as a defeat for Walter Gropius et al and a victory for Mathilde von Freytag-Loringhoven et al. If largely symbolic ones. Bauhaus still employed and attracted artists, Feininger, Klee, Kandinsky to name but three, but focussed, as one imagines they would have in any case, more on applied applications rather than pure art. Or as the new battle cry rang out in 1923, Art and Technology a new Unity. The likes of Mathilde von Freytag-Loringhoven had their beloved art school back, their Realism, Naturalism and landscapes, and thus could claim a connection back to the traditions of the institutions, and thus of the Weimar, of yore.

And thereby a separation which underscores that although in many regards a dispute about forms of artistic expression and the direction of art in the new age, the Bauhausstreit was also about preserving the cultural tradition of Weimar in that new age: with the abdication of the House Sachsen-Weimar all its palaces, parks and institutions passed to the State, a not particularly rich State. For the likes of a Mathilde von Freytag-Loringhoven it was clear that every pfennig spent on Bauhaus was one not spent on preserving Weimar's cultural tradition and, as noted above, that was one of the few things 19th century Weimar still had in 1919.

Thus Mathilde von Freytag-Loringhoven's criticism of the artistic practices and directions at Bauhaus, when, arguably, a genuine and heart felt belief in an art which depicts things that are real, tangible, experienceable, that which she had learned at the Großherzoglich-Sächsische Kunstschule, rather than the abstract, fantasy world of modern, expressionist art, can also be understood as a calculated means to an end: criticise the works the school produces, question the value and relevance of the school, and you can pressure the State to stop funding it. And certainly the 1921 separation did severely cut Gropius's budget, the available money having to be split between two institutions. And that at a time of extreme inflation and general economic instability.

Not that Mathilde von Freytag-Loringhoven's criticism of Bauhaus and Modernist art was however limited to the arenas of art theory and art history, it also took on more sinister forms.

In a 1914 article Mathilde von Freytag-Loringhoven demanded that artists in Germany "cleanse" their art of "all exaggerated French and English admiration and all sought-after Japonism"4 Yes, a war time article and one where the reference to France and England is clearly against the enemy, whereas the "sought-after Japonism" can be considered more as an attack on her personal enemy, and garden thief, van de Velde and his Art Nouveau in general, but is also one of several texts from Mathilde von Freytag-Loringhoven which refer to a (perceived) national Germanic tradition, a subject which post-War became ever more important to defend.

In a speech before Weimar Community Council on December 19th 1919 Mathilde von Freytag-Loringhoven noted that in context of Bauhaus, "... the German students, some of whom are model students, and pragmatic, sensible, capable young artists are, through the behaviour of the foreign students and the preference afforded them by the school management, being morally put to the wall", these foreign students being "primarily Austrians or Hungarians, even, they say, a Russian", before adding that "it is said, that studios are awarded to non-German citizens in which to live and sleep, for free, and in some cases they also receive free food, so I have heard"5 So I have heard. It is said. They say. Preference afforded. For free. As we've oft noted, the language of the divisive has remained unchanged for many a generation. And still works just as effortlessly.

Whereby one must also note that around the same there were troubles afoot at Bauhaus regarding contemporary artistic currents, troubles which reached a head a week before Mathilde von Freytag-Loringhoven's speech when the student Hans Gross was excluded from the school for a speech in which he criticised the lack of a Germanic identity in the school and contemporary art in general; an expulsion which saw in January 1920 further students leave in solidarity and because "since the beginning of the semester the Bauhaus management has tolerated, not to say supported, the international currents within Bauhaus" and that "we cannot accept that our German character is not only undermined by the international trend but should completely recede into the background"6 And thus although, again, essentially a dispute between exponents of classic and modernist artistic expressions, between those adherents of the Staatliche Hochschule für bildende Kunst and those of Bauhaus, was an argument led by questions of race, nationality, national identity.

And while there were, one imagines, hopes, opponents of Bauhaus in Weimar whose criticism was kept to the subjective and artistic, there were a great many who moved it on to the populistic, be that in terms of playing the nationalism, race card, bemoaning the amount of money being spent on the school while the poor citizens of Weimar with their acute post-War needs stood there empty handed, or the (perceived) political leanings of the school and its protagonists, or as Adolf Pochwadt, a close associate of the former Staatliche Hochschule für bildende Kunst wrote in 1919, "Bolshevism has moved into this art."7 And as Design of the Third Reich at the Design Museum Den Bosch neatly underscored, the three principle targets of NSDAP propaganda were Jews, Bolsheviks and Jewish Bolsheviks, perceived or real. And thus in such a statement, and also in the discussions and pronunciations about (a perceived) Germanic art and international students that occurred in and around Bauhaus Weimar, including the numerous utterings of Mathilde von Freytag-Loringhoven, one better understands how in the course of the 1920s the NSDAP exploited the post-War sentiments of the likes of a Mathilde von Freytag-Loringhoven, the reaction of the likes of a Mathilde von Freytag-Loringhoven to the defeat of Germany in the Great War, to the ending of the monarchy, to the social changes in Germany and a dislike, distrust, of new forms of cultural expressions as exemplified by those being developed and propagated at Bauhaus, to their own, abhorrent, advantage.

Which is important in our deeply troubled times, where populism, nationalism, divisive language and a dislike, distrust of new forms of cultural expression are not only rife but inter-mixed in simplistic arguments and memes.

Mathilde von Freytag-Loringhoven wasn't the only critic and opponent of Bauhaus, or indeed the harshest, and indeed Dr Jens Riederer asks in the exhibition catalogue if her weight in the discussion isn't often over emphasised8. Possibly. But it was there, she was a regular and all-pervasive critic of the institution, its staff and pupils, something neatly underscored by Bauhäusler Lou Scheper's 1924 map of Weimar with the text "Brodelei unsauberen Geistes M. Fr. Fr. Lo.....", "Simmering, seething unhealthy spirit of M. Fr. Fr. Lo....." next to the Freytag-Loringhoven home at Marienstrasse 18, a work from the same year in which Mathilde von Freytag-Loringhoven asked "Why was Weimar forced to burden itself with this experiment?"9 - as Volker Wahl elegantly describes Bauhausbeschimpfungen - Bauhaus Insulting - was very much a two way street10, insults being both aimed at and launched from Bauhaus, and an art both sides were highly proficient in, and which both sides engaged in throughout the school's time in Weimar.

And regardless of the place of Mathilde von Freytag-Loringhoven in the wider reality of the period, she is one of the more interesting Bauhaus critics and opponents not only because of the way her biography serves as an accessible conduit for illustrating and understanding the origins and courses of many of the arguments and discussions of the period, but also the relevance of her official positions in the development of the arguments and discussions of the period; and also the inescapable suspicion that in many regards she should have been in favour of Bauhaus, not just because of her own independent, Boheme informed, lifestyle, or her life long committent to allowing women access to higher education, but also in terms of the Weimarer Malerschule, or as Hendrik Ziegler opines, "If one were to attempt to capture the essence of the Weimarer Malerschule in one word, it would be: reduction."11 Bauhaus and cohorts simply reduced further, extended a process that, arguably, began with the move away from academic art. And arguably the path from some of Mathilde von Freytag-Loringhoven's trees, standing as they do isolated from the forest and incomplete in structure, to an expressionist visualisation of a forest, isn't all that long and winding. Arguably only needs to be followed without the breath and mist of the Romantic. In addition we were highly amused by a pair of 1911 watercolours of a ship's cowls, and which allow a line to be drawn from Mathilde von Freytag-Loringhoven over Le Corbsuier to Ionna Vautrin. Which we guess just confirms strange(r) things really do happen at sea.

As an exhibition Mathilde von Freytag-Loringhoven. Painter, Author, Animal Psychologist and Bauhaus Critic helps elucidate such connections and (possible) contradictions and in doing so not only allows for a succinct introduction to the life, work and times of Mathilde von Freytag-Loringhoven but also a succinct introduction to the parallel, antagonistic, highly toxic, worlds that were Bauhaus and Weimar, to the very real conflicts and tensions between the two and the contribution of the manner of much Bauhausbeschimpfungen to a hardening of political attitudes in Thüringen; even if we did and do miss a greater presentation of examples of Mathilde von Freytag-Loringhoven's Bauhaus criticisms, the discussion in the catalogue is fulsome, that in the exhibition a little too sparse.

But hopefully the Stadtmuseum Weimar will find space for a permanent display of some of Mathilde von Freytag-Loringhoven's, and her contemporaries, criticisms: the Stadtmuseum Weimar standing, much as Marienstrasse 18 to Bauhaus, directly next door to the new Bauhaus Museum Weimar. And there is something mischievously delicious in having the criticism and simmering, seething kitchen of a Mathilde von Freytag-Loringhoven existing directly next door to the assumption that Bauhaus was always a popularly received and much celebrated institution in Weimar.

Much as there is something mischievously delicious about the fact that the Freytag-Loringhoven's former family home, that front line in the Bauhausstreit and the simmering, seething kitchen of Mathilde von Freytag-Loringhoven, is now ...... a Bauhaus Uni Weimar student bar and cafe. Honestly, you couldn't make it up! And just imagine how things could have turned out if Mathilde von Freytag-Loringhoven had invited the Bauhäusler in for the occasional coffee or beer. Or put another way, in her memoirs Erika Watzdorf notes of pre-Republic Weimar, "There was always something going on at the Freytags', music, theatre, lectures, entertainment of all kinds..."12 which sounds like the sort of place your average Bauhäusler would have enjoyed, and thus had the Freytag-Loringhoven's continued that salon tradition post-Republic and got to know a few of the Bauhäusler, the Stadtmuseum Weimar could, possibly, now be hosting Mathilde von Freytag-Loringhoven. Painter, Author, Animal Psychologist and Bauhaus Defender.....

Mathilde von Freytag-Loringhoven. Painter, Author, Animal Psychologist and Bauhaus Critic runs at the Stadtmuseum Weimar, Karl-Liebknecht-Str. 5-9, 99423 Weimar until Sunday January 12th

1Antje Neumann-Golle & Jens Riederer, Mathilde von Freytag-Loringhoven (1860–1941). Malerin – Schriftstellerin – Tierpsychologin und Kritikerin des Bauhauses, Stadtmuseum Weimar 2019

2Quoted in Volker Wahl (Ed), Das Staatliche Bauhaus in Weimar. Dokumente zur Geschichte des Instituts 1919–1926, Document Nr 219, Böhlau Verlag, 2009

3ibid

4Quoted in Jens Riederer, "Die Freiin als Fraunrechtler, Feuilletonisten und "Feindin" des Bauhauses", in Antje Neumann-Golle & Jens Riederer, Mathilde von Freytag-Loringhoven (1860–1941). Malerin – Schriftstellerin – Tierpsychologin und Kritikerin des Bauhauses, Stadtmuseum Weimar 2019

5Quoted in Volker Wahl (Ed), Das Staatliche Bauhaus in Weimar. Dokumente zur Geschichte des Instituts 1919–1926, Document Nr 226, Böhlau Verlag, 2009

6Quoted in Volker Wahl (Ed), Das Staatliche Bauhaus in Weimar. Dokumente zur Geschichte des Instituts 1919–1926, Document Nr 247, Böhlau Verlag, 2009

7Quoted in Volker Wahl, "Die Kontroverse um die moderne Kunst in Weimar 1919. Der Beginn des "Bauhausstreits" in Hellmut Th. Seemann und Thorsten Valk (Eds.) Klassik und Avantgarde : das Bauhaus in Weimar 1919 - 1925 Wallstein-Verlag, Göttingen, 2009

8Quoted in Jens Riederer, "Die Freiin als Fraunrechtler, Feuilletonisten und "Feindin" des Bauhauses", in Antje Neumann-Golle & Jens Riederer, Mathilde von Freytag-Loringhoven (1860–1941). Malerin – Schriftstellerin – Tierpsychologin und Kritikerin des Bauhauses, Stadtmuseum Weimar 2019

9Quoted in Volker Wahl (Ed), Das Staatliche Bauhaus in Weimar. Dokumente zur Geschichte des Instituts 1919–1926, Document Nr 361, Böhlau Verlag, 2009

10Volker Wahl, Zum Ende des Staatlichen Bauhauses in Weimar vor 90 Jahren "Bauhausbeschimpfungen" – die andere Seite des Weimarer Bauhauses, Weimar-Jena: Die große Stadt, Jahrgang 9, Heft 2, 2016

11Hendrik Ziegler, Die Kunst der Weimarer Malerschule: von der Pleinairmalerei zum Impressionismus, Böhlau Verlag, 2001

12Erika von Watzdorf-Bachoff, Im Wandel und in der Verwandlung der Zeit: Ein Leben von 1878 bis (1963),Reinhard R Doerries (Ed), Franz Steiner Verlag Stuttgart, 1997

Full details can be found at http://stadtmuseum.weimar.de (German only)