Design of the Third Reich @ Design Museum Den Bosch, ‘s-Hertogenbosch

Whereas the 1920s may have been Roaring, Golden, Années folles, a decade which could be certain that The Great War, that war to end all wars, had brought lasting peace to Europe, and where the utopian visions of the International Modernists, coupled to political and social emancipation and technological progress, made everything possible, and meant we could all gaily Charleston away our nights and days; the 1920s was also the decade that ushered Europe into one of the darkest periods in its history.

With the exhibition Design of the Third Reich the Design Museum Den Bosch explores the role of artists, architects and designers, in helping that darkness settle over 1930s Europe……..

That les Années folles ceded to la plus grande folie has numerous, complicated, inter-twined, reasons, and claiming one reason, or any one component of those myriad reasons, as decisive, is in itself a folly; however, there can be no disagreement that Germany was an important component of the whole. And similarly there can be no disagreement that approaching a better understanding of how Europe moved from gaily Charlestoning away its nights and days to the horrors of war and holocaust involves understanding developments in Germany. Not just in Germany, but certainly in Germany.

As an exhibition Design of the Third Reich* explores just such developments as expressed by and through the objects, imagery and language employed by the Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei, NSDAP, in the years following the appointment of their leader Adolf Hitler as Reichskanzler in January 1933.

Not that 1933 is the beginning of the story, far from it, if accepting that exactly where the story begins is, and as with all deliberations on history, freely debatable; the timeline which opens Design of the Third Reich begins with the cessation of The Great War in 1918 and Hitler joining the, then, DAP in 1919. And goes on to make clear how important the 1920s were for what would come, including the adoption, misappropriation, of the traditional Swastika as the NSDAP’s emblem in 1920, the first Nürnberg Rally in 1927, the design in 1929 by Walter Heck of the SS Rune symbol, and Hitler’s 1924 imprisonment following the failed November 1923 Bavarian coup d’etat: an important moment not only because it signalled clearer than most anything previous the nature of the NSDAP’s intentions under Hitler’s leadership, but also because in prison Hitler wrote Mein Kampf, a work published in 1925, the same year Hitler re-established the NSDAP, and a work which was to become a key building block in the NSDAP’s ultimate rise to power and Hitler’s appointment as Reichskanzler.

That the NSDAP were able to rise to power has numerous, complicated, inter-twined, reasons, as an exhibition Design of the Third Reich largely sidesteps the wider social, economic, political discussions and landscapes of the 1920s and 1930s and concentrates instead on how the NSDAP themselves actively created an environment in which their ideology could thrive, explores, if you will, how the NSDAP cultivated the social and cultural soil of 1930s Germany to allow their ideology to take root and grow. And how architecture and design proved useful, practical, tools in that most poisonous of gardens.

Following a more or less chronological progression Design of the Third Reich opens with a discussion on how the NSDAP attempted to (en)force a unified understanding of a perceived Germanic national identity, a unified understanding of a perceived Germanic Volk, a clearly definable, pure, race which (allegedly) could be traced back through history, and also, and importantly, stressed the superiority of that Volk, and, importantly importantly, that the continued superiority of the Germanic Volk was dependent on maintaining racial purity, and thus a chapter which technically begins pre-1933, but which the curators discuss in its post-1933 expressions, i.e. those expressions realised and disseminated once the NSDAP were in power. Subsequent chapters expand the discourse to discuss how in the years between 1933 and 1939 the NSDAP developed their romanticised/fictitious/noxious narrative of a glorious, superior, Germanic Volk tradition, both on the domestic and international stages, before ending with the aggression, war and mass murder, that unpalatable, sickening harvest of all that had been sown and cultivated since 1918.

And, yes, we did skip through the exhibition layout very quickly, because the progression of the 1930s in Germany is widely known, at least superficially; what Design of the Third Reich does is add an extra depth to that progression, and following the exhibition to those depths and following the arguments made, requires, in effect, ignoring the progression and focussing much more on understanding both the subtle and less subtle means the NSDAP employed in pursuit of their abhorrent goals, and the assistance they had from creatives of all hues in that pursuit.

For all the presence of those less subtle, those more direct, means by which the NSDAP pursued their goals can make Design of the Third Reich at times uncomfortable to view, it is an exhibition, unsurprisingly, not only with a lot of NSDAP imagery, wherever one looks your eyes meet a Swastika, Rune and/or a Hitler portrait, but also with a lot of vile propaganda pushing the NSDAP’s objectionable racial, dehumanising, manifesto; where that led is represented by numerous objects explaining how the non-Aryan were denounced, defamed and discriminated, including a letter from December 1938 proposing five alternative designs for the badge Jews were to be obliged to wear, and asking SS-Gruppenführer Heydrich, then Head of the Sicherheitspolizei, for a decision on which of the five should be employed. And a letter written with all the emotionless disinterest of someone asking their line manager for a decision on which logo should be used for a social media campaign.

The constant, and contextually varied, repetition of Nazi imagery meanwhile helps one approach a better understanding of the way the NSDAP employed the, for want of a better phrase, corporate identity, of the Swastika and Runes to create a sense of State, Empire, even if we’d argue there does appear to be a bit of confusion as to whether the Swastika should stand vertically or be slightly tilted, both representations can be found throughout Design of the Third Reich, but also the extent of the personality cult that was established around the person of Hitler. That such a cult existed is one of those things most of us know about 1930s Germany, the charismatic Führer; Design of the Third Reich allows for an insight into the sheer scale of the industry that was developed to advance the Hitler cult and for all the sheer number of ways Hitler could be brought into your daily life, not just through posters and newspapers but, and much like any 1930s celebrity or film star, Hitler could be consumed though postcards, cigarette cards, booklets, in addition to a whole raft of hagiographic magazines published by the photographer Heinrich Hoffmann and which followed Hitler to, and presented carefully staged-managed photos of Hitler, in Poland, in Austria, on the Western Front, and which in a 1932/33 edition introduced Germany to Hitler wie ihn keiner kennt – Hitler as no-one knows him – and so not as a murderous racist but rather as a chap who likes nothing more than lying around in fields with his dog. A normal chap just like everyone else. And which unquestionably can only have assisted in normalising the image of that particularly abnormal chap.

Lighting and fittings for the Haus der Deutschen Kunst Munich by Atelier Troost, as seen at Design of the Third Reich, Design Museum Den Bosch

Beyond print media a further important medial conduit for the NSDAP was unquestionably radio. Still relatively new in the 1930s as a mass media, and therefore, arguably, all the more powerful on account of its novelty and associated fascination; but a media which in contrast to the self-dissemination of print requires hardware, a receiver, in order to be effective. Design of the Third Reich features two radio devices developed in 1930s Germany and which in their own ways were important for the NSDAP: the so called Arbeitsfrontempfänger DAF 1011 developed by the NSDAP’s (nominal) trades union organisation DAF as an object to ensure every workplace had a radio for keeping employees updated on the latest propaganda, and which thus made the workplace a “front” in their campaign, and the arguably more virulent, Volksempfänger VE 301.

Developed by industrial designer Walter Maria Kersting and, according to Design Museum Den Bosch, his students at the Kölner Werkschule, the VE 301 was not only an affordable, contemporary and readily aesthetically accessible object, but was for all on account of its affordability, mass reproducibility and contemporaneousness widely disseminated amongst 1930s Germans, and thus a device which allowed the NSDAP to bring their twisted world view, pernicious propaganda and fake news directly into neigh on every home in Germany.

Just imagine, a cheap, aesthetically pleasing, contemporary formed electronic device via which you can continuously spread, unchallenged, your falsehoods to individuals as they sit in their own homes of an evening……

……especially when that home, and indeed, workplace are designed as expressions of your ideology.

Chair 104, and Arbeitsfrontempfänger DAF 1011, as seen at Design of the Third Reich, Design Museum Den Bosch

In 1933 the NSDAP established the organisation Schönheit der Arbeit, [Beauty of Labour] with the aim of improving not only physical working environments but also the efficiency of German industry, administration and commerce, and which aside from producing brochures, films and books on contemporary work practices, workplace ergonomics or office design, also promoted and encouraged standardisation of office spaces and office furniture, something blatantly, shamelessly, taken on from the efficiency through standardisation of which the Modernists were so fond. Similarly Design of the Third Reich presents cutlery and crockery commissioned by Schönheit der Arbeit for works canteens; cutlery and crockery showing a tendency towards a rational, functional, typological design that would have appeared familiar to inter-War Functionalist Modernists, and which helps underscore the all-pervasive reach of the NSDAP.

A reach that also extended into the homes of 1930s Germany. Unless we missed them Design of the Third Reich doesn’t present any of the NSDAP’s Christmas tree decorations, does however feature, and amongst other stratagems, a series of magazines explaining to both lays and craftspeople what gute Form is, and objects of home accessories and furnishing which, one presumes, correspond to such, including an armchair simply identified as an “Armchair in NS-Landhausstil” and an object which raises the ever thorny question of can one appreciate something by someone or something totally abhorrent? Can one separate the creator from the work, or are the two one of the same? Can one disassociate the content and message of a work from the appreciation of a work? What is our position on an early 1930s armchair which is without question one of the most engaging, logical, satisfying, appealing, and contemporary, 1930s armchairs we’ve ever seen. But one designed, produced and distributed in service of the NSDAP and the furthering of their wicked, despicable völkische ideology. Can one like it? We can. We do. To paraphrase George Orwell’s opinion of Salvador Dalí, consider it “a good chair from disgusting human beings.”1

Disgusting human beings who didn’t stop at furthering their wicked, despicable völkische ideology through chairs, but who also turned increasingly to aggression and mass murder.

“Armchair in NS-Landhausstil” ca 1933/34, as seen at Design of the Third Reich, Design Museum Den Bosch

In his 1960 film A Problem of Design: How to Kill People, George Nelson, perhaps more eloquently than any one-else, elucidates how since one man first throw a rock at a second, designers have been employed in helping us both kill each other and defend ourselves from the attacks of others, as one strand progresses, so the other, on and on and on and on….. in an endless, pointless, helix of optimisation and technological perfection. Thus it should come as no surprise that the NSDAP made use of designers to help them in their war effort, and among the objects presented in Design of the Third Reich are machine guns as objects of attack, camouflage and steel helmets as objects of defence, and the Wehrmacht-Einheitskanister, the so-called Jerrycan, developed by Vinzenz Grünvogel in 1937, as an object of pure banality; yet as the exhibition explains, a banal object which thanks to its choice of materials and considered, user-focussed, functional, ergonomic, design, was of central importance to the war effort. And a design taken on, copied, by the Americans in 1940, and which became of central importance to the war effort.

In many regards equally banal are the architectural plans presented at the end of the exhibition; or they would be banal, were they not architectural plans for the crematoria and gas chambers at Auschwitz, plans which show that the responsible architects were very much aware of what they were designing, but which exist as thoroughly emotionless disinterested objects, much like a letter asking a line manager for a decision on which logo should be used for a social media campaign. And which thus all the better underscore that architecture and design aren’t passive, that architecture and design, or perhaps better put, architects and designers, are active, that, as we noted, from Objects of Desire. Surrealism and Design 1924 – Today at the Vitra Design Museum, for us, design is the only creative expression that can directly change the world, and that makes it powerful, and dangerous. And demands that we understand design not only as a force for good, but also understand design as a force for evil.

Then, and now.

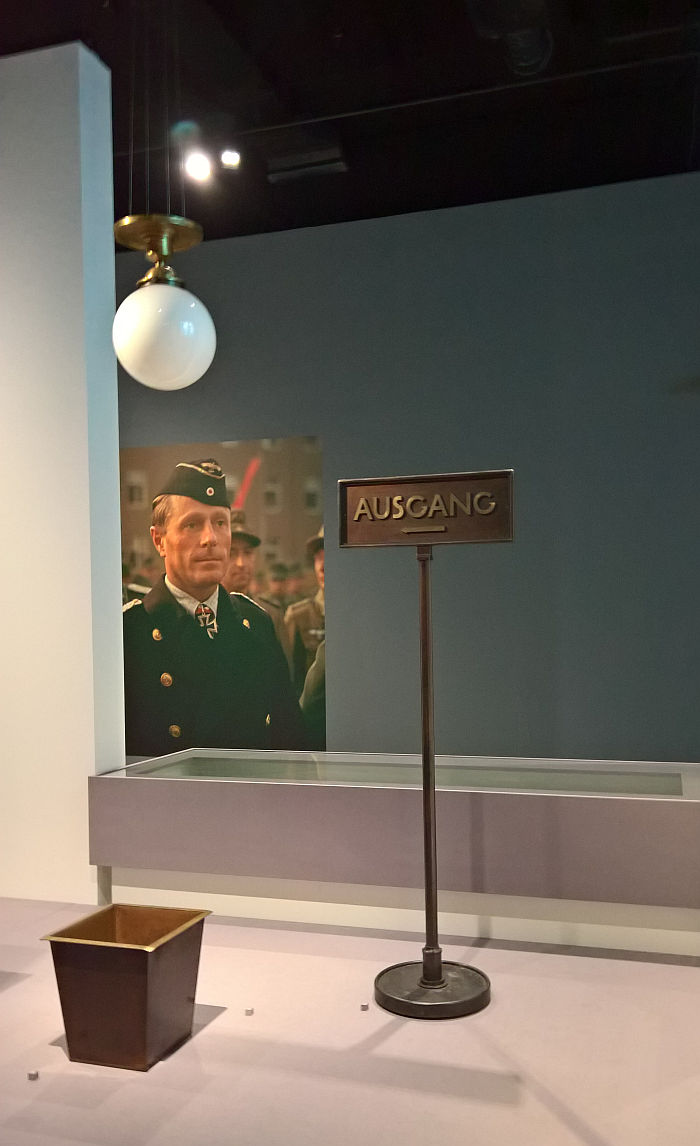

Plans for Ostpreußen, and Luftwaffe officers met their commander in chief, as seen at Design of the Third Reich, Design Museum Den Bosch

On the smow blog office wall hangs a quote from the Polish philosopher and essayist Adam Michnik, a phrase that has been informing and guiding us for more years now than we care to remember, “thinking about history is simply part of reflections about the present and the future”.2 Viewing Design of the Third Reich brings Michnik’s words into very sharp focus. Or perhaps better put foci.

Design of the Third Reich brings into focus the inarguable understanding that many contemporary politicians, publicists and institutions regularly, customarily, employ language and imagery very much aligned to that employed by the NSDAP. Here is neither the time nor place for a deeper discussion, we wish it were, but it isn’t and can’t be, regrettably; however it suffices to say that Design of the Third Reich ably demonstrates that as a society we haven’t learned. We really, really, haven’t.

Design of the Third Reich brings into focus the way design wasn’t only employed directly for propaganda or war and mass murder, but also more indirectly for the reinforcement and normalisation of the NSDAP’s ideology. Whereby the latter is arguably the most interesting foci of Design of the Third Reich, tending as it does to underscore that exactly because design is intimately related with social, cultural, political, economic, technological et al evolutions, that makes it highly vulnerable to abuse and misuse, to a twisting of associations and thus misappropriation for malevolent means, that, and as we learned from Friedrich von Borries. Politics of Design. Design of Politics at Die Neue Sammlung Munich, Design Fetishises, Design Manipulates, Design Forms, Design Disciplines, et al, and that often without the express consent or intention of the designer, through a misuse, a misrepresentation, but which nonetheless less, exactly because?, means that, as Victor Papanek once put it, “There are professions more harmful than industrial design, but only a very few of them”. Design of the Third Reich adds graphic designers to that claim, while at the same time underscoring the responsibility of us consumers to learn to better read and decode that which we consume, that which surrounds us and with which we surround ourselves.

Design of the Third Reich brings into focus the design of the NSDAP in context of the period rather than purely in context of the NSDAP. For all through the wide variety of objects from across genres and time, Design of the Third Reich neatly elucidates that the aesthetic of Hitler’s Germany wasn’t a unified one, far less one that relied purely on the völkische and historic, it wasn’t all tradition, folklore and the monumental, but was one that was very much influenced by the age: standardisation, the industrial production with the new, synthetic, material Bakelite for the Volksempfänger, or the curves and flows of the Volkswagen a.k.a Beetle, as well as the aforementioned cutlery, crockery, Jerrycan, armchair in NS-Landhausstil, or the unquestionable modern form language and expression of a couple of the Jewish star proposals, standing, amongst other exhibits, indicative that contemporary understandings were every bit as prevalent and important as the more historic, folkloric, expressions. Similarly while many of the posters at the start of exhibition are typeset in the Gothic, Fraktur, one normally associates with the NSDAP, as the exhibition progress so does the prevalence of posters displaying comparatively, contemporary, reduced, rational fonts; or put another way, it wasn’t all out with the new and in with the old.

A table by Hermann Burte and the statues Siegerin & Zehnkämpfer by Arno Breker, as seen at Design of the Third Reich, Design Museum Den Bosch

A state of affairs that on the one hand tends to imply that we all need to develop more realistic and probable understandings of the aesthetics, the design, of 1930s Germany, and for all understand that the aesthetics, the design, of 1930s Germany didn’t exist in its own fascist bubble, but arose and existed in context of wider developments of the 1920s and 1930s, albeit with goodly doses of the folkloric, the mythical, the improbable, and that we all need to better question the nature and realities of those relationships and connections.

And on the other hand, tends to imply we all need to consider the, apparently contradictory, question, of in how far the rise of modernist, avant-garde inclined movements contributed to the rise of the NSDAP, in how far the rise in support for the NSDAP in the 1920s was a reaction to institutions such as Bauhaus, in how far a fear of a changing world, a fear of the Utopian visions, social emancipation and technological progress promoted and propagated by the various 1920s avant-garde movements was seized, and abused and misused, by the NSDAP to establish a power base. Including through a dishonest, duplicitous, use of the work of those modernist, avant-garde inclined movements and the associated architects and designers.

Such isn’t new thinking, we’re not breaking into uncharted territory here, such subjects are regularly discussed by academics and theoreticians, are established fields of research, the papers and books are out there, but for us they are discussions that need to be undertaken amongst a wider public and in public forums.

And that not only to allow us to approach a better understanding what happened in 1920s and 1930s Europe, to better understand how European society became so derailed from the humane, from the decent, the respectful, the democratic, the rational, the emotional, the normal, but also as “part of reflections about the present and the future”

Not least in a present and future becoming ever more digitalised, virtual and guided by artificial intelligence, and in which the political language, imagery and personality cult of the NSDAP is, as we learn from Design of the Third Reich, ever present.

We live in dangerous times.

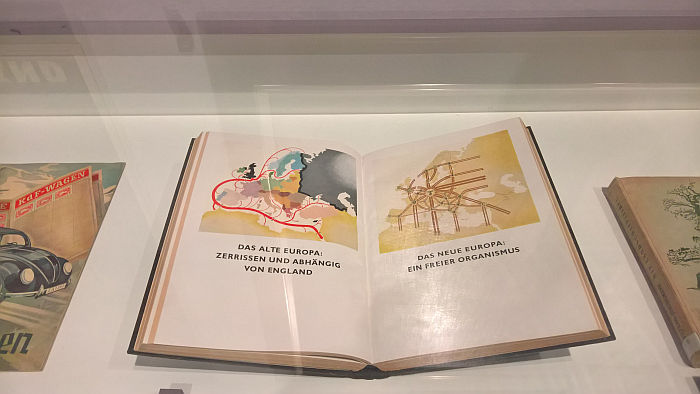

Two pages from the magazine “Raumforschung und Raumordnung”, which read “Old Europe: torn and dependent on England” “New Europe: A free organism” Yes we did swap the words Europe and England, and were amused and terrified in equal measure…..

Ahead of the opening of Design of the Third Reich there was, we think it is fair say, a little controversy, a little concern that it could end up glorifying the NSDAP, concerns given a little more piquancy when one understands that the Design Museum Den Bosch stands directly across a very narrow street from the site of the city’s former Synagogue, a site marked by a plaque commemorating the 293 Jewish citizens of Den Bosch murdered by the Nazis.

And while we’d never underestimate the potential of the malicious to twist the exhibition to their own vile ends, certainly not having viewed Design of the Third Reich, and fully accept that there will be visitors who delight in all that they see, we’d always argue education is important and an exhibition such as Design of the Third Reich can educate.

Can educate contemporary politicians, publicists and institutions as to just how close they sometimes come, do come, to a 1:1 regurgitation of NSDAP imagery and language, and that that cannot be a basis for contemporary discussion and discourse. Our political language must evolve.

Can educate us public to be better aware that that which we consume, that which surrounds us and with which we surround ourselves, may normalise our actions, our perceptions, our relationships to the world around us, our fellow human beings, in ways that may be socially detrimental. That we need to consume more consciously, not just ecologically consciously, but politically and socially.

Can educate designers and architects that their work rarely exists independent of wider political, social, cultural realities and they must be aware of those, and also wary of any attempts to misappropriate their work, their ideas, their positions, for they, more than anyone else are cultivating through their work our social and cultural soil and thereby have a direct influence on that which we harvest. For harvest we will.

But to educate, objects such as those on show in Den Bosch have to be shown. Design of the Third Reich is in no way the first exhibition discussing many of the issues contained within it; however, in its breadth and scope it not only allows for a better appreciation of how art, architecture and design aided and abetted the NSDAP but also makes a strong case for more exhibitions tackling individual components therein. And for all for a discussion on the NSDAP and 1920s and 1930s Germany based on more objects from the period than are normally, publicly, exhibited.

Many of the objects on display in Design of the Third Reich are on loan from German museums, where they are never, or at best rarely, put on show; for us as an exhibition Design of the Third Reich argues we must be braver in addressing the period, we must trust the wider public more, trust that through engagement with history in all its complexities comes understanding of history in all its complexities, and through that understanding, we learn. A museum provides a secure environment for just such engagement. And so while we don’t suspect for a minute any German museum will stage Design of the Third Reich, there are several (design) museums in Germany who should consider it as an opportunity to reflect more openly, and for all in appropriate depth, on questions of design, designers, architects, the NSDAP, the developments of the 1920s and 1930s, and the contemporary relevance of such considerations.

And now is an opportune moment, the broad scope of exhibitions staged in context of the Bauhaus Weimar centenary celebrations have, we’d argue, helped expand the discussion on Bauhaus, have undertaking a little myth busting, and thus means we can collectively move on to develop more realistic, more probable, understandings of the role of early 20th century architects and designers in shaping our world. Including developing a better understanding that design can be an agent of both good and evil.

And that is important because while the fact that les Années folles ceded to la plus grande folie has numerous, complicated, inter-twined, reasons, and claiming one reason, or any one component of those myriad reasons, as decisive, is in itself a folly; there can be no disagreement that understanding the contribution design, and designers, played in helping disseminate, reinforce, normalise, the imagery and language of the NSDAP is important in helping ensuring that future generations can gaily Charleston away their nights and days without fear that war, mass murder and darkness are approaching……..

Design of the Third Reich runs at Design Museum Den Bosch, De Mortel 4, 5200 AA ‘s-Hertogenbosch, until Sunday January 12th

Full details, including information on the accompanying fringe programme, can be found at https://designmuseum.nl

PS. By way of an antidote to all that is on show in Den Bosch we’ve spent a lot of time reminding ourselves that there were those who not only rejected that which the NSDAP propagated, but who fought back, including those who used the objects, language and imagery of the NSDAP in that resistance. Arguably as best represented by the greatest clown this planet has ever known, a clown who established his reputation in silence, but when he spoke, demonstrated he was no clown. We were very tempted to steal his phrase “goose-stepping us into misery and bloodshed”, but we didn’t. Where Chaplin speaks of the radio and the aeroplane, add “the internet and social media.” Rarely was a 80 year old film so contemporary. And if you’ve not watched The Great Dictator, please do….because “You the people have the power……….”

* In the interests of clarity, we’ve deliberately avoided the phrase” Third Reich”, apart from in context of the exhibition title. For us it is an NSDAP term, one not we’re comfortable using, feeling as we do that it tends to imply that the term was somehow “correct”. When it was every bit as twisted as the misappropriation of the Swastika. Similarly we’ve avoided the term “Nazi Germany”, we don’t like the way that tends to separate “Nazi Germany” from “Germany”, as if it was something different, when it was unquestionably, undeniably, a central part of 20th century “Germany”.

** Yes we did consider playing on “Den Bosch” & “The Boche” Space sadly meant we didn’t. But the intention was there.

1. Original quote is that Dalí is “a good draughtsman and a disgusting human being”, George Orwell, Benefit of Clergy: Some Notes on Salvador Dalí, 1944, in George Orwell Essays, Penguin Books 2000

2. Adam Michnik, The Dispute over Organic Work, 1975, reproduced in Letters from Prison And Other Essays, University of California Press, 1987

Tagged with: 's-Hertogenbosch, Den Bosch, Design Museum Den Bosch, Design of the Third Reich