In all corners of the globe one finds objects of furniture which developed in response to local conditions, traditions and practices; vernacular objects without a formal author and which although, on account of?, arising from a very specific place and time can, invariably, both teach us a lot about the essentials of furniture and help explain furniture's relationships with wider realities.

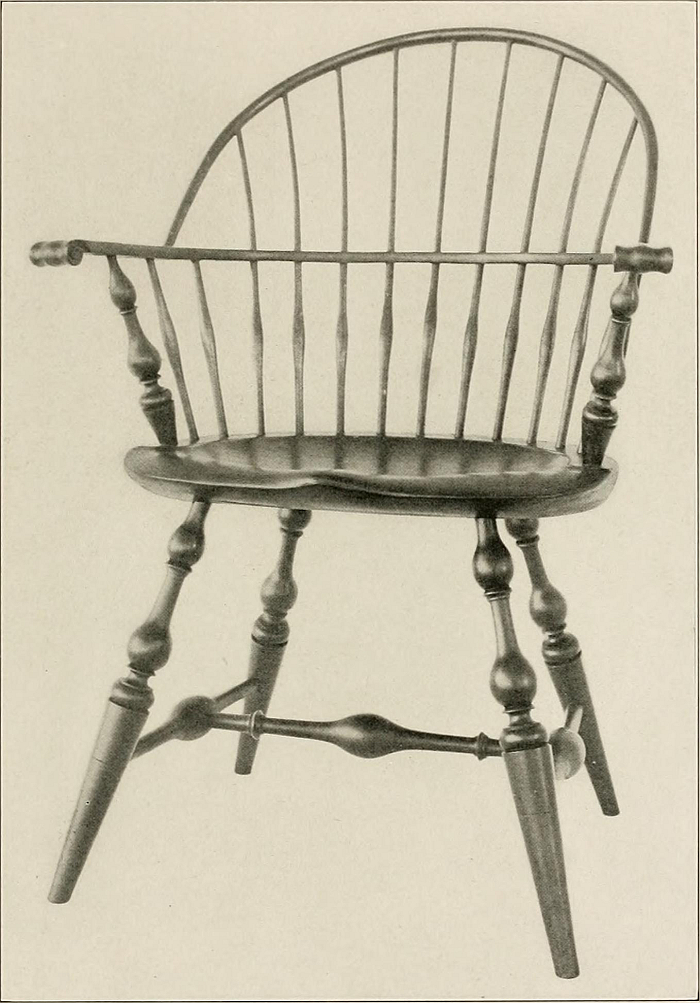

And objects we want to celebrate, starting with arguably, one of the best known examples of vernacular furniture: the Windsor chair.

In his 1917 book The Windsor Chair, Wallace Nutting noted, “The writer has sought to gather in this handbook all that is known of the Windsor, but it is astonishing how little that all is.”1

A century later these writers don't have a great deal more to go on. Or at least only very little conclusive; for despite being one of the very few vernacular furniture objects to have achieved a global fame and popularity, not only do the origins of the Windsor chair2 remain opaque, but also the questions of how it came to enjoy a global fame and popularity remain ones answered more by conjecture than fact.

Every believed move towards an answer simply opening ever more questions. But isn't that the case with so much in life.

Yet, and as with life, we can but try our best, with no guarantees of getting it right.....

Popular convention has it that the first Windsor chairs were, in all probability, made in the 17th century by English wheelwrights; the argument, generally, flowing that in centuries past regulations in England strictly defined which work particular groups of crafts and tradesfolk could undertake, and specifically in terms of woodwork who could make use of which joint types; and many of the standard furniture joints were the exclusive preserve of joiners and cabinetmakers. There being nothing however to stop a wheelwright from making use of a wheelwright’s joints to construct objects other than wheels. And so, by way of generating a little extra income and/or furnishing their own homes/workshops, they did. Initially, so the popular understanding, producing stools; however, as over the course of the 17th century stools with backs, so-called "chairs", became increasingly popular wheelwrights added a spindle back to their stools and thus created a lower cost version of the new-fangled "chairs" which the joiners and cabinetmakers were producing.

And a presumption which, although loaded with unanswered questions,3 tends to be underscored not only by the unmistakable physical similarity of a Windsor chair with a wheel,4 but the production process is/was very similar: whereas the spindles would have been turned from dry wood, the rest of the structure would have been from unseasoned, green wood, the shrinkage of which over time through loss of moisture ensuring the firmness of the joints, and thus a standard wheelwright construction method.

Which all may or may not be true. Is however very plausible.

How such a humble object achieved such a global fame, and why "Windsor",5 are matters of much more conjecture.

And although attempting to forge something more concrete from the pool of conjecture is a highly entertaining and invigorating exercise, one where weeks fly past as if hours as you try to unite the disparate strands, is one we'll ignore at this juncture; too high is the risk that we'll get bogged down in reflections on the Restoration, English garden design, the 18th century London furniture market, Colonialism, cultural appropriation, and the like, and suffice ourselves with the observation that the Windsor chair first becomes clearly visible in England at around 1720.

And at exactly the same time the Windsor chair first becomes clearly visible in America.

Which doesn't make a great deal of sense. Or indeed any sense. Yes, one can understand in the fact that in the early 18th century America was still a British colony a possible means of transfer, but one would expect a lag, a transmission period, that the Windsor chair would become popular in England ... and then the USA; but no, the Windsor chair becomes an established object on both sides of the Atlantic in circa 1720.6

Which, for us, tends to indicate that Windsor chairs were more widely distributed and used in the late 17th century England than history has recorded. But we no know.

What we do know is that regardless of how the Windsor chair arrived in America, it quickly felt at home, and by the middle of the 18th century Philadelphia had established itself as an important centre of American Windsor chair production, and from where by the late 18th century Windsor chairs were regularly shipped south to cities such as Charleston, Savannah and on to the Caribbean, and also north to cities such as New York or Boston, where in the early 19th century they came up with the idea of adding rockers to the end of the legs to create the famed "Boston Rocker".

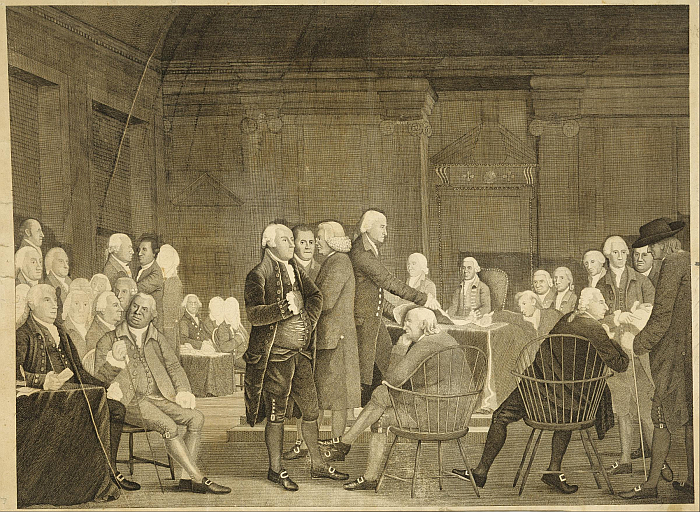

The degree to which the Windsor chair established itself in America can perhaps best be understood by the Windsor chair Thomas Jefferson had in his study at Monticello, Virginia, specifically a revolving Windsor chair, arguably the first ever revolving office chair, and an object which Jefferson had bought in Philadelphia and in which he, allegedly, draughted the Declaration of Independence. Which if true brings a whole new meaning to "the American Revolution". While in Robert Edge Pine's 1780s painting Congress Voting Independence which depicts, not Congress Voting Independence, but the Second Continental Congress's deliberations on the Declaration of Independence, Benjamin Franklin and Charles Carroll are seen sat front centre in Windsor chairs; and in Jean Leon Gerome Ferris's 1776 Writing the Declaration of Independence, while Franklin is this time seated on a more conventional wooden chair, Jefferson's hat can be seen on a Windsor. Albeit not a revolving one. And while the interiors of both Jefferson's Philadelphia apartment and Pennsylvania State House no longer remain intact as they were in the late 18th century, in context of the later history does record that on October 18th 1775 the Pennsylvania State ordered "one Dozen and a half of Windsor Chairs ... for the Use of the House"8. And which all helps very neatly illustrate how, just a few decades after arriving from England, the Windsor chair had become so closely associated with America, had become such a normalised component of American life, had become part of the (hi)story of America's independence and its path to self expression, that one could assume it to be American.

And would soon became so closely associated with Scandinavia, that one could assume it to be Scandinavian.

Popular convention is agreed that it was one Henriette Killander, the lady of Hook House near Jönköping in southern Sweden, who in circa 1850 had the first Windsor chairs produced in Sweden; chairs based on her sketch of a Windsor she had seen, possibly, in America, or possibly, in England.9 But definitely made for her by local carpenter Daniel Ljungquist; and works which obviously caught the attention and imagination of guests to Hook House because Ljungquist was soon busy making such chairs for Killander's acquaintances and neighbours. And not just Ljungquist, demand meaning other local carpenters also took up production of Windsor chairs based on Killander's sketch, and leading in 1863 to the foundation of Sweden's first industrial furniture factory, Hagafors Stolfabrik, near Jönköping in southern Sweden. A factory founded to produce Windsor chairs. And from where the Windsor disseminated throughout Scandinavia........?

Or perhaps better put.

???

For just as much of the story of the spread and establishment of the Windsor chair in England and America is uncertain, so much of its (hi)story in Scandinavia. A (hi)story made especially difficult by the existence of the so-called Budalsstolen, a chair produced around Budal, near Trondheim, Norway, the oldest example of which dates to 1807, and a chair which bears an uncanny resemblance to the Windsor, so much so that one must assume it was based on a Windsor. But by what means did the concept of the Windsor chair reach such a remote location as Budal in the late 1700s/early 1800s? And by what means did the Windsor chair reach Denmark? And did it get there before the 1940's?10

Yet regardless of the exact mode of arrival of the Windsor in Scandinavia, and the mechanisms of the dissemination throughout Scandinavia, the Windsor unquestionably felt every bit as at home in Scandinavia as in England and America, and since the 1940s, through works by the likes of, and amongst many, many others, Børge Mogensen, Carl Malmsten or Ilmari Tapiovaara, the Windsor has not only become synonymous with furniture design in Scandinavia, but the Scandinavian Windsor has almost become the definitive Windsor.

If not always in forms that the wheelwrights of 17th century England would understand as a Windsor.

But then the process of formal reinvention, the voyages of formal discovery, and when one considers, for example, Jefferson's office Windsor or the Boston Rocker, the voyages of functional discovery, that the Windsor chair has undertaken over time and geography, are in many regards inherent in an object that arose free of context, other than as a sitting object that could be produced by local craftsfolk from local materials to meet local needs; that which defines the Windsor is, on account its scantness, strict, but open to free interpretation. In many regards the first wheelwrights of the Thames Valley, assuming it was them, created less a chair as a framework for chair design. Even if they didn't, couldn't, appreciate that fact.

And this free adaptability and variability without impinging on the essence of the object, the, inherent, open invitation to continually consider it anew without losing touch of the original, is arguably part of the reason for not only the enduring popularity of the Windsor, but why it established itself so firmly, first in England, then globally.11

But only part.

Other reasons can be found in those two essentials of any furniture object: form and function.

While it is relatively easy to make aesthetic arguments in favour of the Windsor chair, we'd argue those are contemporary arguments, arguments based on contemporary appreciations of reduced, formally light objects, of objects whose simplicity of materials and construction are as much metaphoric as physical. No one was thinking about such in 1720. Really, they weren't. Such is a contemporary affliction. If still very valid

Or put another way, in the later decades of the 19th century, the Windsor chair enjoyed a revival in England, thanks in no small part to perceived associations of simple cottage life in contrast to the developing industrialisation of the period, and subsequently, in the middle of the 20th century, the Windsor in its formal and material reduction found itself fitting in very nicely with the formal demands of the inter-War Modernists, or more accurately those Modernists who remained with wood rather than switching to metal, one thinks, for example, of works such as Josef Frank and Oskar Wlach's 1930s Viennese Windsors, or post-War the rational, formal reduction undertaken in Scandinavia. While it can be no coincidence that the only existing design included in the UK's Second World War Utility Furniture Scheme was a Windsor chair from 1877, nor is it we'd argue a coincidence that that same chair is still produced today as the only surviving example of Utility Furniture. And thus for a century and half the Windsor chair has stood, in one way or another, as a textbook example of a furniture ideal, of a design ideal, of "good taste"; and thus for a century a half the Windsor chair has been a near ubiquitous furniture object. Whereby one must never lose sight of the fact that such is largely contemporary understandings being read, found, in the Windsor chair rather than new understandings being derived from the Windsor chair. The Windsor chair can teach us a lot, but we prefer to use it to confirm that which we want to say, to provide a legitimacy for our arguments. Which doesn't mean a well formed Windsor isn't pleasing on the eye and calming on the mind, it very much is; is however to understand that our aesthetic understandings aren't innate, but taught. Yes, should be learned. But are invariably taught.

And while the aesthetic charms of the Windsor may not have been the reason for its adoption in the 18th century, associations similar to the 19th century cottage life associations alluded to above, may have been.

As may have its functional charms.

One of the more popular strands of the (hi)story of the Windsor chair that we refused to discuss earlier is that it, possibly, first found a widespread use and popularity in the gardens that developed in the country estates of England in the late 17th/early 18th centuries, those heavily landscaped gardens which sought to reflect a naturalness, an idealized naturalness; and faux-natural spaces in which a Windsor chair passed not just formally, but metaphorically, underscoring through its material, simplicity and humbleness that naturalness of the space, certifying an authenticity. Much as a century and a bit later it would stand proxy for the idealized humble simplicity of the country cottage. And thus, if one so will a semantic functionality. While, at a more practical level, thanks to the nature of their materials and construction, Windsors were weatherproof, light to transport and thus could be freely moved about the garden as required, while being (relatively) cheap could be bought in large numbers without impacting overly on the household budget.

A relatively low cost, combined to a relative ease of production, which no doubt also helped the Windsor make the transition from the gardens of the nobility and landed gentry to the homes of the middle orders, not least those members of the London middle order keen to stay abreast of contemporary upper order fashions. And a relative low cost and ease of production which are arguably not irrelevant when one considers, for example, the need to refurnish London following the Great Fire of 1666 or the need of the many, poor, early 18th century British settlers in the United States for affordable furniture; as an object which could be quickly supplied in the large numbers the Windsor chair, one presumes, would have been a relatively easy choice.

Then there is the fact that for all its simplicity the Windsor chair features, and as best we can ascertain, always has featured,12 a shaped seat, a saddle-esque form rising to a ridge front-middle; and a facet of the Windsor chair that, for us, is far too little researched, for shaped wooden seats weren't that common in late 17th/early 18th century England, yet have the advantage of being more comfortable than unshaped, i.e. flat, wooden seats and are cheaper, and more convenient, than upholstered seats. And also cheaper and more convenient than the woven wickerwork seats that achieved a popularity in England in the 17th century. And thus there is a very satisfying logic in understanding the uptake of the Windsor as being partly on account of its seat, its seating comfort.13

And a seat which was formed by the unfortunately titled "bottomer", a craft which helps explain another important facet of the Windsor chair, and one which, arguably, has contributed to its enduring popularity: it was produced through the assembly of prefabricated components supplied from a range of craftsfolk.14 Specifically, while the bottomers crafted the seats, so-called bodgers turned the spindles and legs, benchmen created the central splats found in may English models, benders formed the bentwood components, and framers brought the whole thing together before finishers and varnishers smoothed it all off and, when required, varnished them.15

And thus the Windsor was perfectly predisposed for industrial production. Or more accurately, the Windsor was perfectly predisposed to follow developments from craft production of furniture to industrial production of furniture.

And that around a century and a half before Michael Thonet's bentwood process enabled mass, serial, furniture production. Indeed one could argue that with his bentwood process Michael Thonet broke the joiners' and cabinetmakers' monopoly on furniture production and thereby allowed for a democratisation and repositioning of furniture forming and production every bit as elegantly as the wheelwrights of 17th century England once had.16

Assuming it was them......

But regardless of who it was, reflections on the Windsor chair, reflections not just on it as physical object but on its many (hi)stories, reflections on the whats, whys and wherefores, reflections which rarely end in answers but invariably lead on to more questions, such reflections allow for the development of differentiated and much more probable understandings of what furniture is, allows for an extension of our understandings of the inter-twinning of the (hi)story of furniture and the (hi)story of wider society and thereby not only enhance our understanding of the Windsor chair but enhance our understanding of what we can all learn from the study of furniture as the cultural good it is.

Reflections we implore you to undertake.

1Wallace Nutting, A Windsor Handbook, Wallace Nutting Incoporated, saugus, Massachusetts, 1917

2While there is no official definition of a Windsor chair, we as with in most things, will go with John Gloag: "chairs and seats of stick construction with turned spindles socketed into solid wooden seats to form back and legs" [ John Gloag, A complete dictionary of furniture (Revised and expanded by Clive Edwards), Overlook Press, Woodstock, New York, 1991]

3Not least the question of arms, i.e. did the very first have arms or not? Armchairs were still relatively rare in the late 17th century but most all early 18th century Windsor chairs have arms.....

4A key feature of any Windsor chair, and to expand on the definition, is the use of bentwood, which isn't a normal component of "joiners' chairs". The combination of turned and bentwood not only giving the Windsor its characteristic appearance, but tending to confirm a genesis outwith conventional furniture practice.

5It is important to note that the term "Windsor" has been used since the early 18th century, that, as Robert Parrot notes, the “Windsor chair is probably unique in being the only item of English period furniture named after a place, with the name known to have been in use for nearly 300 years and not a later term invented by the antiques trade.” [Robert Parrott, Observations on the Earliest Known Windsor Chairs, Regional Furniture. The Journal of the Regional Furniture Society, Volume 19, 2005, page 1ff] The "Windsor" in Windsor chair is almost certainly a reference to the English town, Windsor, but in which context, and why, is a subject of continuing debate.

6The earliest recorded reference to a Windsor chair is in 1708, in the will of a certain John Jones of..... Philadelphia. [see, eg., Esther Singleton, The furniture of our forefathers, Doubleday, Page & Company, Garden City, New York, 1913] Everyone assumes that Jones was English and had brought the chair with him from England. But no one knows. One of the first mentions in England is in the March 1723 inventory of the contents of Chevening House, Kent, which noted the possession of "60 Windsor Chairs painted Green...." Painting green was popular in the 18th century, and alongside "Windsor" such chairs were, often referred to as "Forrest chairs". Which may also give clues about their origin. Or may just have been a fashion thing. [Robert F. Parrott, Forrest chairs, the first portable garden seats, and the probable origin of the Windsor chair, Regional Furniture. The Journal of the Regional Furniture Society, Volume 24 2010, pp. 1ff

7The first recorded Windsor chair in Jamaica is from 1735, and thus, more or less parallel to its appearance in England and America. And thereby tending to underscore the important role British colonialism played in the early dissemination of the Windsor chair, see, John Cross, The Transference of Skills and Styles from the American to Jamaican Furniture Trade During the Eighteenth Century, The Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts, Winter 2004 Volume 30, Nr. 2, page 49ff And for more information on the distribution of Windsor chair from Philadelphia see Harold E. Gillingham, The Philadelphia Windsor Chair and its journeyings, Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, vol. 55, Nr. 4, 1931 page 301ff

8see Nancy A. Goyne, Francis Trumble of Philadelphia: Windsor Chair and Cabinetmaker, Winterthur Portfolio, Vol. 1 ,1964, page 236, 237 & FN 58

9Henriette Killander's model is interesting in that it is of a fan back type with no armrests, which although not unknown, arguably wasn't the most common type. Has however become a popular Scandinavian understanding. see Josefina Hägg, Livet på en pinne - ett designarbete med pinnstolen som utgångspunkt, Examensarbete i Möbeldesign, Carl Malmsten Furniture Studies, Stockholm, page 12. Accessible via media.hagaforsstolfabrik.se/2019/08/tqde10_josefinah%C3%A4gg_Examensrapport.pdf (accessed 15.07.2020)

10We may have missed something here, and certainly the current limited access to libraries doesn't aid and abet such research, but tracing the path of the Windsor to Denmark is all but impossible. Certainly before 1940. Unless we are just missing something very obvious, which is possible. But if we're not, there seems to be a lot of research needed on the history of the Windsor in Denmark. And Finland.

11The variability of the Windsor can also be found and appreciated in the myriad regional expressions of the Windsor that arose in England, local adaptations and variations that allow those initiated in the ways to pinpoint the location of any given Windsor's production with an accuracy that would make GPS blush.....

12Or at least, always once the Windsor became established. We imagine the very, very first models didn't have formed seats. Also the 1807 Budalsstolen has a unformed flat seat, see https://www.adressa.no/nyheter/okonomi/2015/10/23/Budalen-f%C3%A5r-ikke-retten-til-Budalstolen-11711171.ece (accessed 15.07.2020) Whereby it's interesting to note that whereas the Windsor chair Henriette Killander had made for her by Daniel Ljungquist had a ridged, saddle-esque, seat, today one encounters more regularly Scandinavian Windsor chairs with more concave seats, a development which may or may not be attributable to Carl Malmsten......

13Not that we believe that in 18th century people would sit down and say "my, what a comfortable chair", furniture as something that can and should be comfortable is relatively new; however then as now people would prefer to sit on something that doesn't hurt....

14The Windsor wasn't unique in being realised through such a process, such process were common at that time and were largely predetermined and unavoidable on account of the very strict separation of the jobs different crafts and trades could perform.

15Which doesn't stand in contradiction of the theory that the first were made by wheelwrights, but rather is indicative of how as production increased the process evolved and became more organised, formalised. And eventually industrialised.....

16It's worth noting here that Michael Thonet's wood bending technique was also a wheelwright's technique, something he acknowledged in his 1856 Privilege application, claiming the "newness" was its use for furniture. [see Jiří Uhlíř, Vom Wiener Stuhl zum Architektenmöbel: Jacob & Josef Kohn, Thonet und Mundus; Bugholzmöbel vom Secessionismus bis zur Zwischenkriegsmoderne, Böhlau Verlag, Vienna, 2009] If Michael Thonet knew that the Windsor chair makers had been there a century and a bit earlier is unknown....