"Trunk-hasped, cart-heavy, painted an ignorant brown. And pew-strait, bin-deep, standing four-square as an ark"1

Reading Seamus Heaney's musings on his Settle Bed one could be forgiven for considering it a thoroughly unremarkable object. Ignorant even.

That would however be to misunderstand the nature, spirit, essence, of poetic construction. And the nature, spirit, essence of the Settle Bed.

As discussed ad infinitum, ad nauseam in these dispatches, the settle was a near ubiquitous object of furniture in, largely, though not exclusively, rural, homes of Britain and Ireland from the middle ages until the 20th century. Essentially a wooden settee, a goodly number of settles feature an exaggerated high back which allowed them, when placed with their front to the fire and their back to the outside door, to both act as a form of room divider and to help keep sitters warm of a cold evening in the draughty cottages of yore. Settles with shorter backs are however not uncommon and would generally have stood against a wall, the backrest allowing for a, degree, of protection from the damp and cold of the wall. Aside from providing a place to sit, the settle was, thanks in no small measure to its simple construction principle, an extremely adaptable, versatile, object that could, and did, serve a number of additional functionalities; as previously discussed many versions offering storage space. And, possibly, in some higher backed versions, space for the curing of bacon.

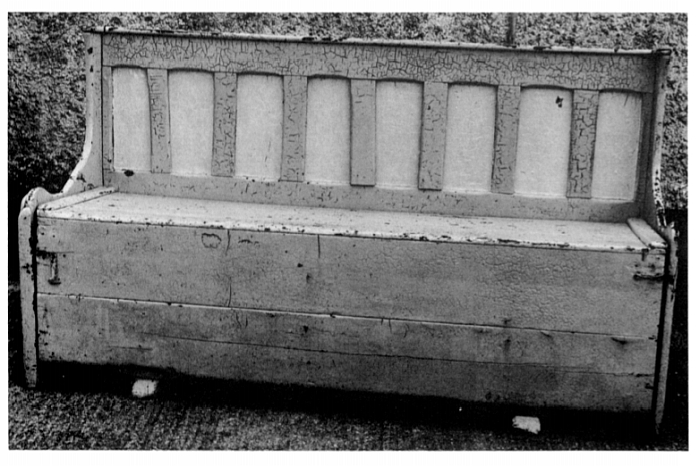

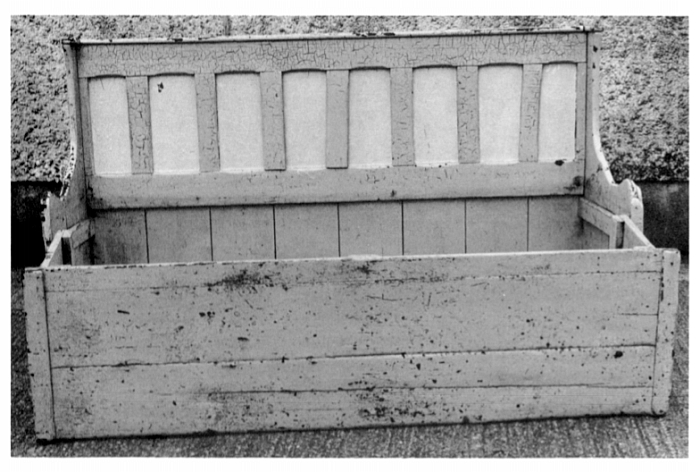

The Settle Bed, as the name neatly implies, was a settle that was also a bed. An early, the first?, sofa bed. And that with an audacious simplicity: by day a standard settle, come evening the seating part could be simply tilted forward, unfolded as it were, to form a rectangular box, within which was the bedding. And which come morning could be quickly folded back up to a bench.

Which is clearly genius.

And which, yes, makes it a little bit like a coffin, or as Heaney notes,

"If I lie in it, I am cribbed in seasoned deal Dry as the unkindled boards of a funeral ship. My measure has been taken, my ear shuttered up."

But mainly it's genius.

And from where came this genius?

Oh but we knew!

However, and as with so many, all?, vernacular objects, no-one saw fit to record the origins and early history of the Settle Bed, far less the name of that first carpenter who, realising the seat box was underutilised space, asked themself, what if......? And so our considerations on the origins of the Settle Bed, invariably, become lost in the mists of time. If alighting regularly upon the island of Ireland.

According to Claudia Kinmonth2 the earliest recorded Irish Settle Bed can be found in the 1640 inventory of John Skiddy Snr. and John Skiddy Jr., father and son merchants based in Waterford and scions of a larger Cork dynasty3; Kinmonth also recording a further half dozen references in the course of the seventeenth century including eight at Dublin Castle in 1684. Throughout the 18th and 19th century the number of references to, and thus one presumes, prevalence of, the Settle Bed in Ireland increases, not only in number but in scope: whereas all the seventeenth century references are associated with wealthier households, by the 19th century the Settle Bed's distribution is more universal, more democratic, and it is found across class and privilege.

An increasing scope of distribution which Kinmonth, through a combination of direct references and documentary evidence, backed-up with indirect association, argues can be understood as meaning that the Settle Bed, possibly, originated as a servants bed, and that it (may have) spread to poorer sections of Irish society when those servants returned to their home communities and commissioned a local carpenter to make them one. Or indeed the local carpenters who, having made examples for the big houses, took the initiative and built one for themselves, their families and neighbours. And thus, arguably a move up from the long time rural Irish practice "of sleeping 'in stradogue' (from the Irish srâideog ('a floor bed')), whereby the whole family (and perhaps the visitor) slept one next to the other on the floor, all covered with a single large blanket or mat."4

And which as an argument isn't implausible, and there is indeed something very appealing about the thought of a cabinet maker primarily employed to create high value objects suggesting to a landowner the Settle Bed as a cheap and amenable bedding solution for the staff. And for all one that during the day takes up no space, requires no separate room, and thus reduces both the cost of the servant and their footprint on the estate. An essentially functionalist solution.

Would however implode the understanding of the vernacular as something arising from the unconscious, subliminal, communal will of the anonymous masses. Which we're loathed to do. But happy to do where the evidence demands. Yet that evidence we haven't seen.5 Just a very convincing argument in that direction. In addition, one must always remember that there are only very few, no, records of the inventories of early 17th century Irish peasant homes, and that it isn't inconceivable that such inventories would reveal Settle Beds, which then found their way to the big houses as a cheap and amenable bedding solution for the staff, one which those staff were familiar with, which any local carpenter could produce. And which, and as with its (possible) use in the traditional single room cottages of rural Ireland, took up no space during the day and required no separate room.

What is however clear is that by the 19th century the Settle Bed was a firmly established feature of the rural Irish household; reading between the lines it appears that neigh on every family was in possession of one, and where it served a number of functions; beside regularly being used by family members, it was often kept as a spare bed for travellers looking for shelter for the night, and also often found use as a bed for young children, not only could they not fall out, but its closed form (ideally) stops them wandering about should they wake in the night.

The use of the Settle Bed in Ireland was however not only physical, but also metaphysical, metaphorical. In, for example, George Fitzmaurice's 1908 play The Pie Dish one Margaret, on thinking her aged father is about to die, has her sons place him in the Settle Bed so that the priest can perform the Last Rites. He is, as it were, thus "cribbed in seasoned deal." Upon seeing this Margaret's sister Johanna bemoans the mistreatment of her father, that a Settle Bed is no becoming, respectful, place for a dying old man, for a dying father, that her sister is behaving uncharitably, and, and one senses the real reason for her horror, "there's a great shame on you to be having him there and the people coming in to you"6: the Settle Bed being something historic, archaic, to be embarrassed about in contemporary society. An historic understanding of a different kind being found at the end of the 20th century in Brian Friel's 1982 play The Communication Cord where the Settle Bed serves as a component of a heavily romanticised image of an Ireland past, the sort of inauthentic, reconstructed, image that all too often serves as the basis for an overly romanticised sense of national identity, or as Dr Donovan describes it, an image that is "somehow central to my psyche".7 And indeed Heaney's musing on his Settle Bed also have something of the romantic, if a much more grounded romantic, the Settle Bed in question being one he inherited from a family member8 and whose incorporated memories were personal, and thus allows him to reflect on the,

"Long talks at gables by moonlight, boots on the hearth, The small hours chimed sweetly away so next thing it was The cock on the ridge-tiles."

And thus with all their chatting failing to use the settle as a bed.

And a personal, if highly poeticised, memory, Heaney' still constructing, that invariably adds to the pool of collective romanticised memories of the Settle Bed and thus collective romanticised memories of rural Ireland of yore, a romanticised rural Ireland that is central to so many psyches. Yet a personal memory that is also, for all its poetic license, a very nice example of how furniture becomes part of our lives and thus part of our biographies. Even something as unassuming as a Settle Bed. It's not the furniture you own, but how you use it.

And thus given the very important place the Settle Bed enjoys in the physical and cultural fabric of Ireland, and certainly more so than in any other nation state or society we can identity, is the Settle Bed an Irish development?

Claudia Kinmonth is convinced that it is. And she is not alone.

And while we are in no sense in any position to even begin to consider the possibility of contradicting that view, and happily concede that the widespread physical and symbolic use would appear to support it; on the one hand, there doesn't appear to be an Irish Gaelic term for "Settle Bed", which surely there would be if it was of ancient Irish origin. And on the other Claudia Kinmonth supports her argument to a degree on the claim that the Settle Bed "does not occur in the history of furniture from Scotland, Wales or France" while claiming its existence in England is limited to a single object recorded in a single inventory from 1641.9

Which are claims worthy of more reflection..........

The aforementioned 1641 English Settle Bed belonged to the courtier and art collector Thomas Howard, Earl of Arundel and Surrey, or more specifically was located in Countess Arundel's home, Tart Hall on the edge of St. James's Park in London,10 and not only does its location within Tart Hall and the nature of the furniture around it tend to imply it wasn't a servant's bed, but it is and was far from the only reference to a Settle Bed in 17th century England.

In, for example, George Etherege's 1676 comedy The Man of Mode the unnamed shoemaker tells the rake Dorimant that "there's never a man i' the town that lives more like a gentleman with his wife than I do", noting amongst other examples of his propriety, "and because 'tis vulgar to lie and soak together, we have each of us our several settle-bed".11 Thereby implying that the Settle Bed was an established object in late 17th century London, an object theatre-goers would be familiar with; and something tending to be supported by Sasha Handley who notes that a Henry Mosse of West Ham and a Richard Holmwood of Richmond were both in possession of Settle Beds in 1688.12 Handley opines that, based on the further inventories of the two gentlemen, both beds were designed to accommodate "guests on an ad hoc basis", which, if true, on the one hand reminds us of the use in Ireland as occasional bed for travellers and on the other would make them a different beast from those implied by Etherege's shoemaker. But that of course may be part of the joke, the shoemaker erroneously, ignorantly, believing it normal for London gentlemen to sleep in Settle Beds. And which brings us back to the, possible, origin as servants bedding in Ireland.

And that they weren't just a common piece of furniture in 17th century London can be gleaned for example, by Eric Mercer's (unreferenced) comments that early seventeenth century inventories from northern England "sometimes mention a "long settlebed" or a "long settle bedstead"",13 while one Thomas Spencer from the Vale of Glamorgan, Wales, was, upon his death in 1682, recorded as being in possession of a Settle Bed.14 And 19 cheeses. Which seems extravagant. Although sadly no note is made of how large, or small, they were. 19 cheeses? Ridiculous! But we digress..... The more important point is that such and similar examples not only provide evidence that in 17th century England and Wales, as in 17th century Ireland, the name Settle Bed was established, that the term was contemporary, isn't, as so often with furniture, an invention of later generations, but also provides evidence, when however limited, that the Settle Bed was known and was used in 17th century England and Wales.

Alone amongst the peoples of Britain and Ireland do we struggle to find the Settle Bed in Scotland.15

Do however have more luck in New England.

Martha Finch, for example, notes that Myles Standish, the English Army officer commissioned with protecting those Europeans who landed in America on the Mayflower in 1620, possessed, upon his death in 1656 in Duxbury, Massachusetts, five bedsteads, including one Settle Bed.16 In addition, in 1655 one Major Peter Walker had a Settle Bed in his house in Northampton County, Virginia,17 while on his death in 1674 in Westmoreland, Pennsylvania, Captain John Lee was recorded as being in possession of a Settle Bed.18

As far as is recorded, certainly as far as we understand, the Mayflower passengers brought no furniture with them, and so, logically, had furniture made upon arrival. And although we don't know when or why Myles Standish et al had their Settle Beds made, their existence would tend to underscore the importance of the Settle Bed in daily life; one would, presumably, only invest in commissioning that which was needed and used. And in the mid-17th century the Settle Bed clearly was. And was.

While the existence of the Settle Bed in mid-17th century New England raises the question, if those individuals emigrating from England to America in the early-17th century brought the Settle Bed with them, is it not conceivable those who emigrated from England to Ireland in the early-17th century would have done the same?

And if immigration brought the Settle Bed to Ireland, what role Irish migration in its dissemination?

In 1985 the Canadian Postal Service issued three new stamps in their Heritage/Patrimoine series, the 39¢ stamp featuring a Settle-bed, a Banc-lit. And through doing so places the Settle Bed, as observed in Ireland, as a component of a (perceived) national identity, as an object integrated into the cultural fabric of the nation. Yet, and again as with Ireland, there is very little record of its Canadian origins. John Mannion19 opines that it may have been brought to Canada by 19th century Irish settlers; whereby, as with the first European immigrants to the contemporary USA, its unlikely that they would have brought actual furniture them, and much more that they would have brought not only the skills to make them but the understanding of the relevance and practicality of the Settle Bed in daily life. Plus, as Mannion opines, "as in Ireland the restricted floor space in the small loghouses of Peterborough and Miramichi necessitated the continuance of the settlebed."

And while we'd certainly support such a theory, it would appear to be only part of a wider picture. That the Canadian Settle Bed could be considered as international in its composition as the contemporary Canada. That far from symbolising an abstract Heritage/Patrimoine the Settle-bed/Banc-lit, could, represent something much more tangible.

The European colonisation of the contemporary Canada began in the early 17th century, the English establishing themselves on Newfoundland from 1610 while the French established a colony at Quebec in 1608; and in context of the later Donald Blake Webster, in his review of early French-Canadian furniture in the Royal Ontario Museum, opines that "French-derived Quebec furniture before the mid 19th century followed French fashions and styles", there being according to Webster no furniture designs of that period, "that do not have a stylistic counterpart in France", albeit the Quebec objects often exist as an expression adapted to the local conditions and realities.20 And thus, the early 19th century Settle Beds in the Royal Ontario Museum collection must have, and contrary to Claudia Kinmonth's claim, had a French antecedent, or...........?

"The settle-bed was a particularly Quebec form, the banc lit, derived from the French banc-coffre", opines Webster.21 Much to our confusion

For although a theory which is satisfyingly logical, and could also explain the wider origins of the Settle Bed as a refinement of the settle's storage function, would tend to imply that the Quebec Banc-lit developed independently of the English/Irish/Welsh Settle Bed. And that some two hundred years, and 5,000 kilometres, later.

????

However, there are a couple of alternative routes to the Banc-lit.

The French, largely Breton, Lit-clos, a box bed, room-in-room construction, often featured a long, low, wooden box along the front and thus during the day, with the doors closed, functioned, essentially, as a settle. The Banc-lit is realised by "simply" placing the larger box inside the smaller box. Which is more a philosophical challenge than a technical one.22

Much more tantalising however is Eric Mercer's noting of a 1507 inventory of the Duke of Bourbon's estate that lists eight benches, "dont il y en a ung qui est fait pour servir de couchette", "of which there is one that is made to serve as a bunk."23 As Mercer notes, how that was achieved isn't recorded, but what if, what if, et qu'est-ce qui se passerait si .........?

The Settle Bed a 16th century French invention? Really? Is that possible? Or are we getting unnecessarily excited? Do we need to calm down?

Yet regardless of how the Banc-lit arose its, apparent, independent, coexistence alongside the Irish Settle Beds in early 19th century Canada tending to imply that the Canadian Settle Bed is of cosmopolitan origin, an object closely associated with human migration and colonisation.

An implication enhanced by an early 19th century québécois Settle Bed The Canadian Museum of History possess with a stick back, a thoroughly charming object if one of only limited use as a settle; and a stick back which raises the question of its provenance, it being arguably much more of an English/US persuasion than French or Irish......Or?

And is also a very interesting example of form not following function. The function hasn't evolved, the form has.

And would continue to do so.

The Settle Bed isn't just one of the earliest expressions of a sofa bed, but one of the earliest expressions of that which Sigfried Giedion so deliciously describes as "the domain of convertible beds that may assume the shape of other furniture by day or may disappear into the wall and even into the ceiling."24 And that as Clive Edwards notes one the one hand from "a very real need for space-saving, and a concern with hiding this necessity" amongst poorer sections of society and an on the other as an idle "fascination with adjustable and secret furniture" amongst those wealthier individuals who had "no particular space-saving requirements."25

The former being neatly represented by the various alcove-esque bed solutions that have been employed across cultures and history, including those found in the traditional, so-called, Black Houses of the Scottish Isles but also the wall-mounted, folding, double beds that were installed in the Praunheim housing estate realised as part of the mid-1920s Neues Frankfurt project, apartments where space was, almost by definition of the Die Wohnung für das Existenzminimum – The Dwelling for the Living Income Earner - ethos which underscored Neues Frankfurt, in very short supply.

The latter being neatly represented by the endeavours of 19th century Patent furniture inventors, Giedion saving for posterity, and amongst other works, Charles Hess's 1866 "Improved Piano, Couch, and Bureau", a work of outrageous, out of control, fantasy, and which aside from being a piano, couch and bureau, also included a concealed bed, no honest; and also by objects such as a late-18th century Commode Bed assigned to Georg Haupt and to be found in the Royal Palace, Stockholm,26 a work featuring in addition to an elaborately ornate exterior appropriate for a Royal Palace, a very cleverly resolved bed frame extension technique which saw the bed pulled out from within, and thus a variation on the 18th century Bureau Bedstead where the bed folded out from within a object pretending to be a bureau, or as Oliver Goldsmith described the genre in 1770,

"The chest contrived a double debt to pay, A bed by night, a chest of drawers by day"27

Yet regardless of how technically ingenious and/or decorative such objects may be, they are passive objects, objects which when not in use as a bed stand in the room inactive, mute; the Settle Bed is/was anything but, as both a settle and a bed it contributed actively, articulately, to the space. Similarly the contemporary sofa bed. Yet whereas the sofa bed (near) always involves accepting a degree of compromise - a sofa bed is rarely as comfortable as either a sofa sofa or a bed bed - the Settle Bed is compromise free.28

In addition the sofa bed is, as are the numerous mimicking, concealed variations, reliant on technical solutions in varying degrees of complexity, and the associated constructions, materials and inherent weaknesses. The Settle Bed was a carpenter's solution that does nothing more than cut a cube across the diagonal so that it can open to reveal its true character.

Which is, as noted, genius.

Yet despite this much noted genius, and the very obvious importance and relevance of the Settle Bed to previous generations and previous societies, and thus to the development of both furniture and society, today it is lost.

Lost not just in the sense that they don't physically exist today, and that despite their inarguable appeal, relevance, contemporaneousness for contemporary society with its restricted domestic spaces and need for responsive, proactive, furniture solutions, or as Heaney says of his Settle Bed, "In the long ago, yet willable forward."

But also lost in the sense that its memory exists more in romance than in what the (hi)story of that simplest of furniture objects can teach us about furniture, the (hi)story of furniture, the development and evolution of furniture, functionalism and furniture, furniture as cultural good, the relationship(s) between furniture and the individual, furniture and society.

And also what the Settle Bed teaches us about the importance of the vernacular in the (hi)story of furniture, that the (hi)story of furniture isn't just one of architects and designers stamping their names on objects and culture, nor about the furniture of castles, cathedrals, palaces et al, but is also one of objects of every day use developed anonymously for no greater reward than to meet the particular, collective, demands and needs of individuals regardless of wealth, education, training, et al. And of objects regularly achieving that with a logic and honesty that not only saw them become established in their own time, but subsequently allowed them to develop alongside society.

To remain true to themselves, yet to continually evolve.

Or, and to return to Seamus Heaney, his Settle Bed and the power of the carefully constructed poetic metaphor in the hands of one who understands such,

"Then learn from that harmless barrage that whatever is given, Can always be reimagined, however four-square, Plank-thick, hull-stupid and out of its time It happens to be."

1and all further Seamus Heaney quotes, Seamus Heaney, The Settle Bed, in Seing Things, Faber & Faber, London, 1991

2Claudia Kinmonth, Irish country furniture. 1700-1950, Yale University Press, New Haven, 1993

3Julian C. Walton, The household effects of a Waterford merchant family in 1640, Journal of the Cork Historical and Archaeological Society, Vol. 83, No. 238, 1978

4Barry O'Reilly, Hearth and home: the vernacular house in Ireland from c. 1800, Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy: Archaeology, Culture, History, Literature, Vol. 111C, Special Issue: Domestic life in Ireland, 2011

5The nature of the times mean that there are a couple of texts that could/would be important, but that we were unable to reference, or at least not without an undue wait. But that others quote from them, we assume there is nothing in them that would fundamentally change our opinion, if something that may cause us to reflect deeper. In particular we think of Alan Gailey, Kitchen Furniture, Ulster Folklife Vol 12 1966 and Fionnuala Carragher, Settle Beds in the Ulster Folk and Transport Museum, Ulster Folklife, Vol 31 1985. We are still on their trail, and should after reading them this post requiring updating, we will do so.

6George Fitzmaurice, The Pie-Dish: A play in one act, Leopold Classic Library

7Quoted in Margo Regan O'Flaherty, Dancing at Lughnasa: the carnivalesque in Brian Friel's plays, MA Thesis, Department of Drama, University of Alberta, 1993

8For more on Seamus Heaney's Settle Bed see Bernie McGill, The Settle Bed. The story behind the poem https://www.rlf.org.uk/showcase/the-settle-bed/ (accessed 28.08.2020)

9Claudia Kinmonth, Irish country furniture. 1700-1950, Yale University Press, New Haven, 1993

10Lionel Cust, Notes on the Collections Formed by Thomas Howard, Earl of Arundel and Surrey, K.G.-II, The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs, Vol 20, No 104 November 1911

11George Etherege, The Man of Mode or, Sir Fopling Flutter, 1676

12Sasha Handley, Sociable Sleeping in Early Modern England, 1660–1760, History, Vol 98, No. 1 January 2013

13Eric Mercer, Furniture 700-1700, Weidenfeld, Nicolson, London, 1969

14Moelwyn I. Williams, Agriculture and Society in Glamorgan, 1660-1760, PhD Thesis, University of Leicester, 1967

15But we've not given up looking. Obvs. But in these days such takes a little longer

16Martha Lawrence Finch, Corporality and Orthodoxy in Early New England: Plymouth Colony, 1620-1692, PhD Thesis, Religious Studies, University of California, Santa Barbara, 2000

17John C. Coombs, Building "The Machine": The development of slavery and slave society in early colonial Virginia", PhD Thesis, The College of William and Mary in Virginia, 2003

18ibid

19John Joseph Mannion, Irish Imprints on the landscape of eastern Canada in the nineteenth century: A study of cultural transfer and adaptation, PhD Thesis, University of Toronto, School of Graduate Studies, 1971

20Donald Blake Webster, Rococo to rustique; early French-Canadian furniture in the Royal Ontario Museum, Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto, 2000

21ibid

22We find it very hard to refer to the Lit-clos without referring to Ronan and Erwan Bouroullec's 2000 Lit clos realised for and with Kreo Gallery, Paris. A contemporary re-imagination by two Breton of a concept closely related to Brittany. To paraphrase Heaney "In the long ago, yet willable forward."

23Eric Mercer, Furniture 700-1700, Weidenfeld, Nicolson, London, 1969

24Sigfried Giedion, Mechanization takes command. A contribution to an anonymous history, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, 2013

25Clive Edwards, Press Bedsteads, Furniture History, Vol 26, 1990

26see ibid for photos

27Oliver Goldsmith, The Deserted Village, 1770 https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44292/the-deserted-village (accessed 28.08.2020)

28Compromise free in the sense that the width of the sleeping box is the sum of seat height and seat depth. If we consider regular dining chairs then we're talking +/- 45 and +/- 52 which gives you a width of between 90 and 100 cms which is single mattress territory and thus fine for a single adult or two small children. If however you want a bed box that two adults can comfortably use, it gets trickier, then your looking at wanting something of at least 160 cms, which means an awkward sitting height and/or an impractical depth requiring of back cushions. Or you integrate an extension mechanism, which yes takes us into the realm of technical complexity, but could also be understood as an evolution.....