In 1977 the German designer Luigi Colani demanded a "renaissance of Art Nouveau"1

What he meant, why he meant it, and if it is something we should all fear, can be explored and considered in the exhibition Luigi Colani and Art Nouveau at the Bröhan-Museum, Berlin.......

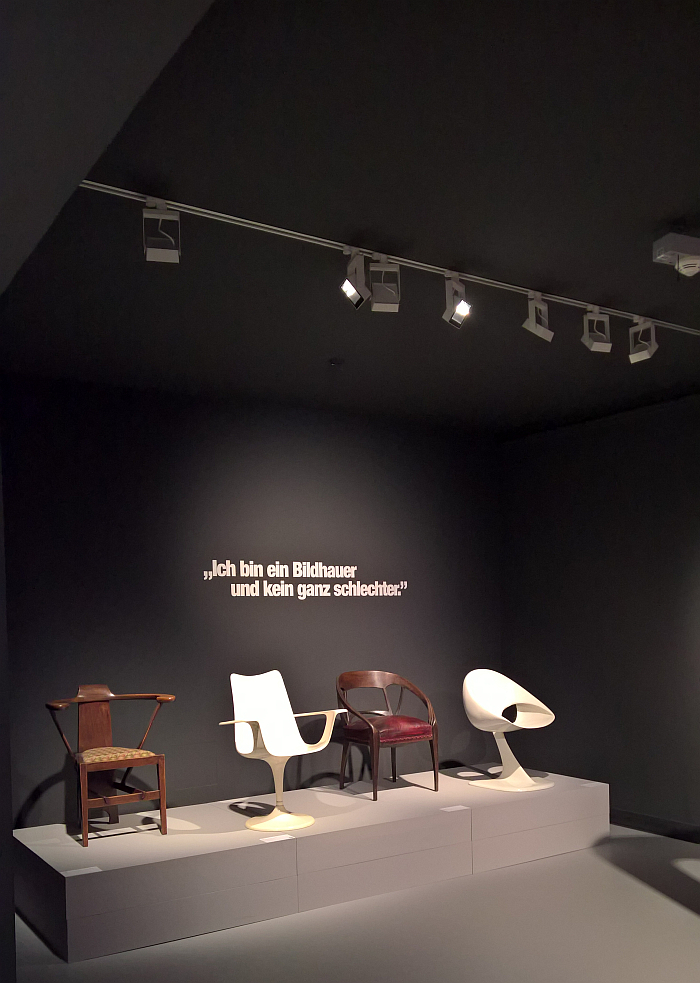

Born in Berlin on August 2nd 19282 Lutz Colani3 studied sculpture at Berlin's Hochschule für bildende Künste between 1946 and 1948, before moving to Paris where he studied aerodynamics at the Sorbonne; and the city where both Luigi Colani's Art Nouveau and the exhibition Luigi Colani and Art Nouveau begin.

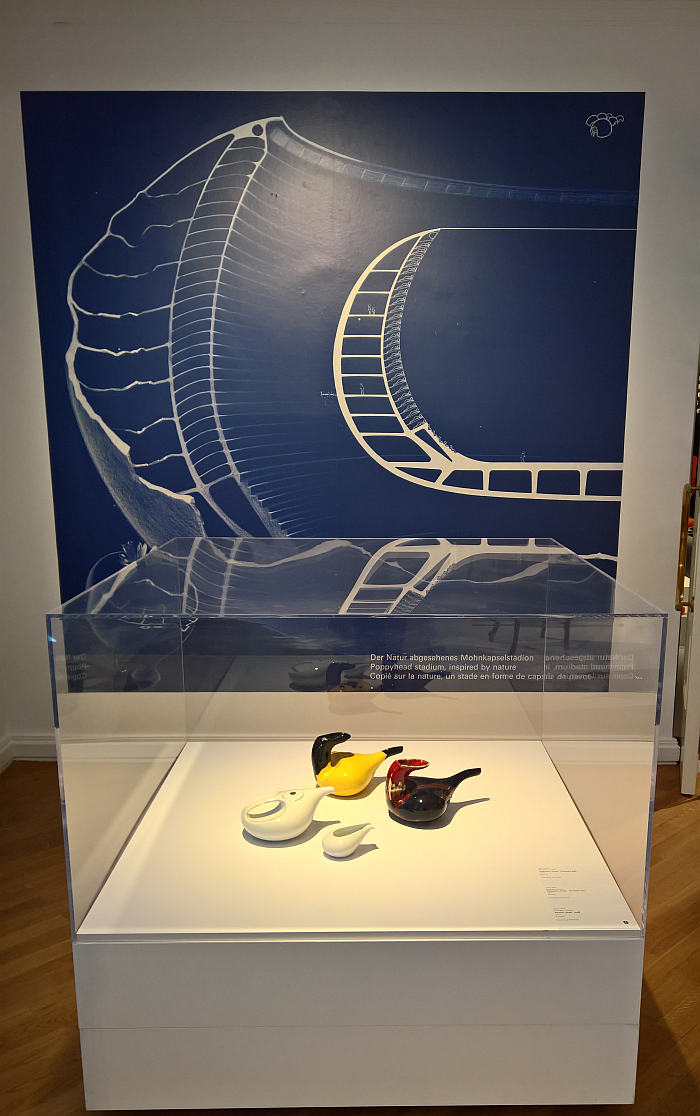

Specifically with furniture and ceramic designs by Hector Guimard alongside Guimard's metalwork and signage designs for the Paris Metro, which and whom stand representative of the highly, overly?, ornate florid of French Art Nouveau, a highly, overly?, ornate florid expression, dialect, of Art Nouveau echoed in Luigi Colani and Art Nouveau through works by, and amongst others, the Catalan furniture designer Joan Busquets i Jané or glassware from the Loetz Witwe works in Bohemia, and an expression, dialect, of Art Nouveau, which, the curators argue, was to serve as a key reference for Luigi Colani's understandings of and approaches to design.

An argument taken up, expanded and discussed in the neighbouring rooms, for all in context of associations with nature and sensuality: the former, an understanding and position not only that humans are part of the natural word and thus the objects of our daily use should, must, be so designed as to reflect the flowing curves and rounded forms of nature, but for all should, must, be designed to compliment the human form, should be designed in context of, and with reference to, the human form, human needs.

The latter as both an erotic and emotional trait, energy?, and a trait, energy?, expressed for all through the female form, or better put, through heavily idealised female forms, and a sensuality not only reflected in the meandering contours and gentle undulations regularly found in works of both French Art Nouveau and Luigi Colani, but which in their celebration of the freely expressed, naked, unashamed, human body caused minor indignation in both early 20th century Europe and post-War West Germany.

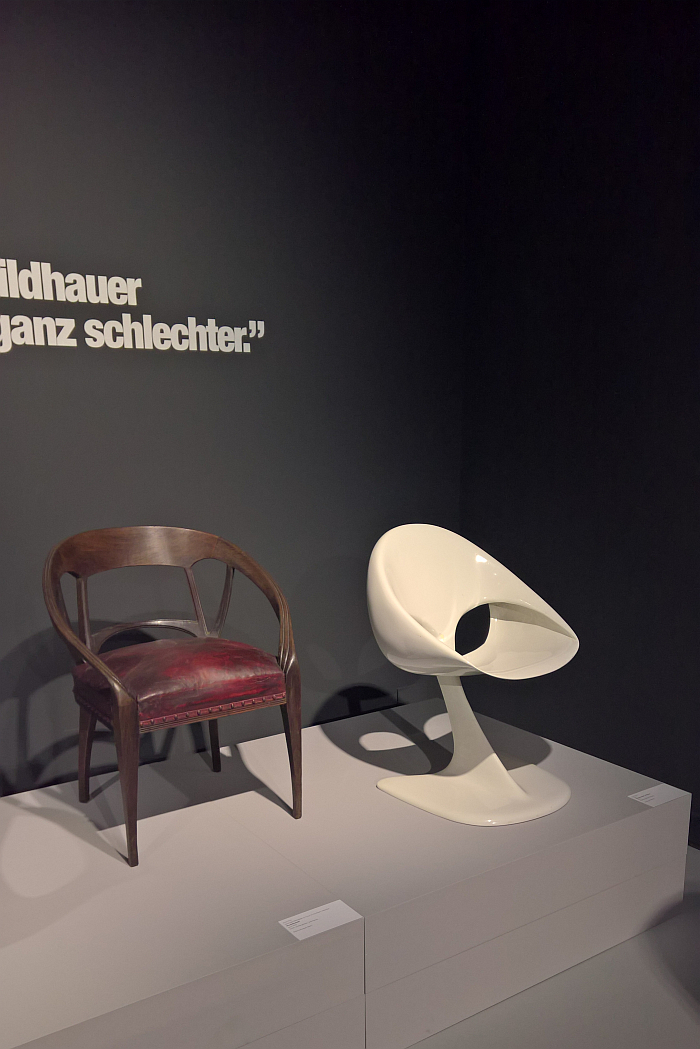

And a discussion undertaken in Luigi Colani and Art Nouveau through a presentation of works by the former and also of works by the former in dialogue with works from the early 20th century including, and amongst other conversations, a 1902 armchair by Richard Riemerschmid for the Dresdner Werkstätten für Handwerkskunst Hellerau alongside Colani's 1973 Ringnor stackable children's chair; a Bruno Paul armchair from ca. 1902 for the Vereinigte Werkstätten für Kunst im Handwerk, Munich, and Colani's 1968 Polycor chair for COR; or an upholstered lounger by Paul Iribe from 1913 opposite an upholstered lounger by Luigi Colani from 1970 realised in collaboration with the German chemical conglomerate BASF. 1970 also being the year in which Verner Panton presented his famed Visiona 2 installation in collaboration with the German chemical conglomerate Bayer, and which thus allows for a moment of contemplation on the formal, conceptual and contextual similarities and differences between a Luigi Colani and a Verner Panton, on Panton and Art Nouveau?, thoughts advanced by the volumes of cursive coloured plastic that surround you, and thoughts that keep you so busy that all of a sudden you find yourself in Margaret Lihotzky's 1927 Frankfurter Küche.

And think, Eh!?!?

But then almost instantaneously that Eh!?!? turns into a chuckle, before the delicious thought of Luigi Colani having contributed to Neues Frankfurt, that enduring symbol of inter-War Modernist Functionalist ideals, causes one to laugh out loud. Not that humouring visitors is the primary reason for the kitchen's inclusion. That can be found much more in an photo of, but sadly no actual, kitchen Colani presented in 1970 in conjunction with Poggenpohl, a one-piece moulded plastic pod in which one sits enveloped by the kitchen environment, everything you could need within easy reach. And which on the one hand very satisfyingly juxtaposes Colani's understanding of a human scale kitchen, a kitchen designed in context of, and with reference to, the human form, human needs, with Lihotzky's understanding of a human scale kitchen, for lest we forget the linear, and formally reduced, Frankfurter Küche was developed in accordance with early 20th century Functionalist ideals on standardisation, for all on the basis of Taylorist principles of optimisation, and thus, as with Colani's kitchen, designed in context of the user.

Same same, but very very different.

And on the other hand reminds of the one-piece cast concrete kitchen Lihotzky developed prior to the Frankfurter Küche in context of her work with the Viennese Siedlerbewegung, and that an early 1920s one-piece cast concrete kitchen is in many regards exactly the same as an early 1970s one-piece moulded plastic kitchen; its all evolving materials and technologies opening up new possibilities in context of prevailing social, economic, cultural, et al realities and about designers understanding design as more than the creation of objects but as a responsibility to the individual and the collective.

And then you regret the loud laugh, and your accusative Eh!?!?, because you've suddenly, and effortlessly, understood something about Luigi Colani and his place on design's helix.

And leave the kitchen happy. And contrite.

Only once again to find yourself thinking Eh!?!?, as you stand confronted by a collection of early 20th century wooden furniture by Peter Behrens, Josef Hoffmann, and other German and Austrian Art Nouveauists. But no Luigi Colani juxtaposed.

Yet this time there is no chuckle, just a second, Eh!?!?, and then you, or at least we, think.... Hoffmann.... Behrens.... Colani.... moustache.... and thus since visiting Luigi Colani and Art Nouveau we've been primarily preoccupied, obsessed, with viewing images of Art Nouveauists moustaches, and Ettore Sottsass's, and now understand Luigi Colani's moustache as also being an essentially Art Nouveau work: just image him in a high-collared frock coat with his hair tidied up a bit. Perfect! In addition Luigi Colani's Jugendstil Moustache is without question the great missing Mogwai song title. But we digress....

And you're still fully absorbed in your Eh!?!? as you wander into the next room and read Luigi Colani's opinion that "Das Bauhaus ist out. Outer geht's gar nicht mehr", "Bauhaus is out. Outer is impossible", written above a display of, predominantly, quadratic metal furniture. But pleasingly it's not "Bauhaus" furniture. Rather is a presentation of some very interesting 1930s tubular steel objects produced by Prague based SAB, accompanied by, and amongst other objects, a wire-glass commode by Gerrit T Rietveld for Merz & Co Amsterdam, a steel floor lamp by Miloslav Prokop für Napako, Prague, and a wooden chair by the ex-Bauhäusler Erich Dieckmann realised in 1928 for the Frankfurt Employment Office and which (a) is a joy, (b) reminds that just as the late 1920s wasn't just tubular steel furniture, late 1920s Frankfurt wasn't just Ernst May and Neues Frankfurt, and (c) just how important Dieckmann was. And just how forgotten he is.

But for all one is taken back to the early 20th century wooden furniture by Behrens, Hoffmann et al and from where you retrace your steps to Modernism, stopping this time a little longer at the French Art Déco works by the likes of Pierre Chareau or Jacques-Émile Ruhlmann, and in doing so approach an understanding that although much German and Austrian Art Nouveau began with a florid symbolism every bit as free-flowing and decorative as their French colleagues, and of which Behrens and Hoffmann are two excellent illustrations, it (quickly) became increasingly rational, increasingly geometric, increasingly symmetric, and that this geometric rationalisation, and simplifying irresponsibly, flowed on through to Art Déco and the inter-War Modernists, something that can, arguably, be most directly understood in terms of Bauhaus Weimar's fixation with the ○, □ and △

And which brings you back to the highly, overly?, ornate florid expression of Art Nouveau.

And for all to Luigi Colani's Art Nouveau.

That Luigi Colani was the opinion that "Das Bauhaus ist out. Outer geht's gar nicht mehr", shouldn't be understood as a criticism on or of Bauhaus, in many regards Colani was very much pro-Bauhaus, certainly Weimar Bauhaus; his criticism, his problem, was much more how that Bauhaus legacy, how the wider legacy of the inter-War Modernist Functionalist avant-garde was transposed and interpreted post-War, for all in context of West German design. Or perhaps better put, how Luigi Colani understood post-War West German design as a lazy, dishonest, and for all formulaic, continuation of pre-War understandings rather than the necessary development, or, arguably, the necessary correction.

Or as he once phrased it, how post-War West German design with its focus on, primacy afforded to, inter-War Functionalism, represented an, "ultra-conservative attitude towards design, which does not yet dare to question Bauhaus ... this ultra-conservative attitude is the fundamental problem"4

A "fundamental problem" Colani understood as being particularly prevalent, endemic, in one particular sector, "take a look at what our big furniture manufacturers are doing. What rubbish, right? Those angular boxes, this ultra-conservative basic idea that is repeated over and over again and sold for tens of thousands ..... the industry is stupid. The furniture industry is damn stupid"5

"Angular boxes" arising from an "ultra-conservative attitude towards design" and a general rejection by Colani of the quadratic, liner, geometric in product and furniture design which reminds very much of that other unapologetically moustachioed post-War designer Ettore Sottsass's (alleged) statement that "when I was young, all we ever heard about was functionalism, functionalism, functionalism. It’s not enough. Design should also be sensual and exciting",6 an understanding that objects have functionalities beyond the physical, that they are also emotionally functional, an emotional functionality that can be found at the core of Colani's understandings, or as he once phrased it, "we want to rediscover the human and break the linear, human beings have no straight lines"7

And the way to that was, for Luigi Colani, a "renaissance of Art Nouveau", and for all a renaissance of the highly, overly?, ornate florid expression and dialect of Art Nouveau.

In many regards Luigi Colani's rejection of the primacy of the geometric in design recalls memories of the so-called Typisierungsdebatte, Typing/Classifying Debate, which reached a head at the 1914 Deutsche Werkbund exhibition in Cologne, and where, and by necessity of space simplifying more than is advisable, Hermann Muthesius argued in favour of the use of unified forms in architecture, for a universal standardisation to aid and abet construction, whereas Henry van de Velde argued for the independence of the individual artist, for the primacy of the artistic process.

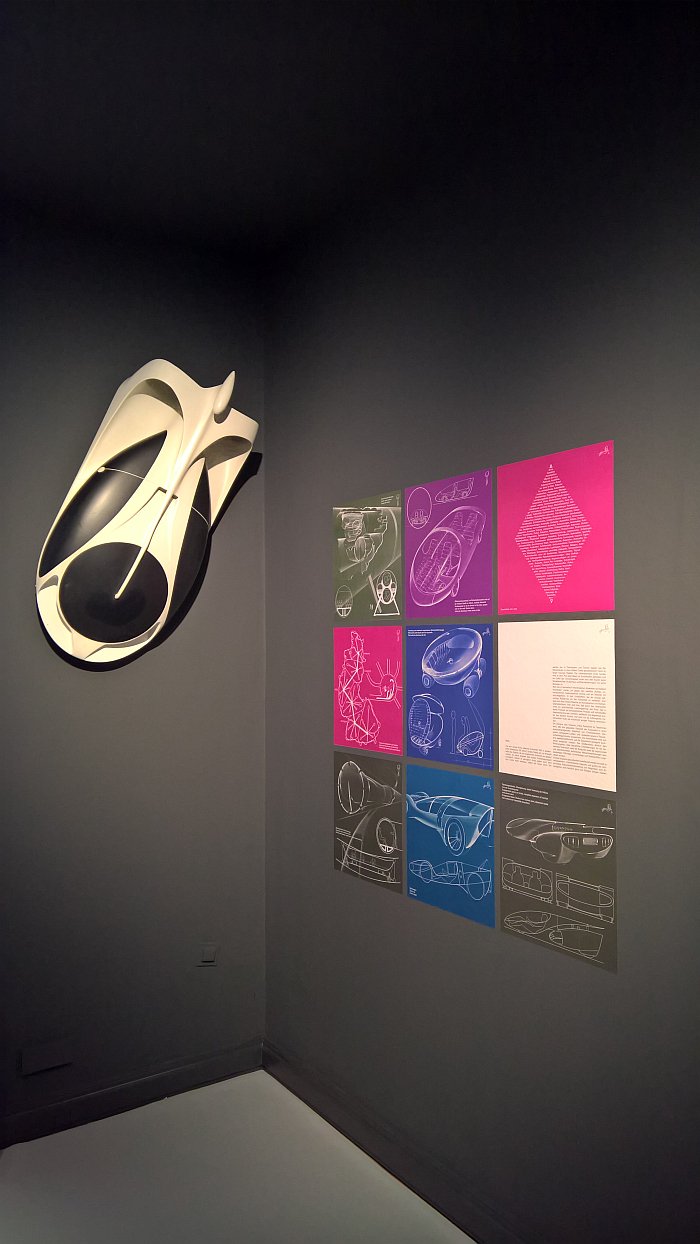

Colani's position in such a debate is, and certainly after viewing Luigi Colani and Art Nouveau, relatively easy to deduce. And much as van de Velde, that Grand Doyen of Belgian Art Nouveau whose "modern Belgian curvatures" appalled and terrified many of his Dutch contemporaries in a way that Colani's modern curvatures would appal and terrify many of his contemporaries, much as van de Velde's argument was based on his artist's understanding of the world, so Colani's; an understanding that arguably began in childhood, but more certainly developed at the Hochschule für bildende Künste, the Sorbonne and also in his brief tenure in the early 1950s with the Douglas Aircraft Company in Santa Monica, California, where he worked in the New Materials department, and thus not only an early introduction to the industrial application of new, synthetic, materials, but for all a first opportunity to practically combine the freedom of sculpture with the laws of science and the forms of nature to create functional design.

An understanding that allows one to recognise that Luigi Colani's renaissance of Art Nouveau was also an evolution of Art Nouveau; that whereas in Art Nouveau the floral was largely decorative, symbolic, instructive, with Colani the flowing lines and rounded curves are functional.

And an understanding which turns one's thoughts to the progression from the heavy ostentatious decoration of the first decades of the 19th century, its reduction and ordering by the early Art Nouveauists and its continuing reduction, rationalisation and eventual removal on the path to the decoration free geometry of Modernism. The path to Luigi Colani, we'll argue, is the same, is one undertaken with similar intentions, just Colani didn't remove the highly, overly?, ornate florid of Art Nouveau, but made us of it, rationalised it and optimised it until it achieved a functionality. While ensuring it never lost its inherent sensuous excitement and emotion.

Not that Luigi Colani was the only post-War designer to develop works with flowing forms, aside from the aforementioned Verner Panton one could name, and amongst many, many others, a Pierre Paulin, a Joe Colombo or an Eero Saarinen, while amongst those who began their careers inter-War an Alvar Aalto is a fairly unavoidable example. As indeed is an Arne Jacobsen, whose own relationship to nature and Art Nouveau we discussed and hypothesised on in context of the exhibition Arne Jacobsen - Designing Denmark.

The singular on Luigi Colani, so the exhibition narrative, is the very deliberate and considered step back he took to the highly, overly?, ornate florid of Art Nouveau and how he moved forward from there as an artist not as a designer, and which thereby brought him out at a same same, but very very different location, and a same same but very very different formal expression of functional design.

Although superficially a Luigi Colani exhibition, Luigi Colani and Art Nouveau is one whose internal dialogues and close coalescences mean it is as much about Art Nouveau as about Luigi Colani, in many regards uses Luigi Colani as a conduit by which to approach a better understanding of Art Nouveau, and uses Art Nouveau as a conduit by which to approach a better understanding of Luigi Colani. That, arguably, the title should be, Luigi Colani. And Art Nouveau.

Something particularly neatly understood in the liberal use of pages from Colani's 1971 publication, manifesto, Ylem throughout the exhibition space, both as background material to aid and abet understandings of the various themes, but also as an insight into Colani's understandings of society, of humanity, and of how humanity and society could, should?, develop and progress. The date of the publication reminding anyone who hasn't already done the math, that Colani's positions to and understandings of society, culture, humanity arose in context of the evolutions and revolutions of the 1950s and 60s, and which all became very tangible with the events of 1968 and the oil crisis of the early 1970s. And thus that Luigi Colani's design understandings arose against the background, and in context of, those evolutions and revolutions. That his design isn't about a "style" but is about a response to prevailing realities and the question(s) of where and how humanity and society could, should?, develop and progress. A response in which Colani was informed by Art Nouveau.

And that not randomly, certainly not without reason.

Art Nouveau being itself not a "style", wasn't something that spontaneously developed, but rather was understandings and approaches that arose from and in context of a period of social, cultural, political, economic, et al evolutions and revolutions, and thus that design which we classify as Art Nouveau is a response to prevailing realities and the question(s) of where and how humanity and society could, should?, develop and progress.

And although the contexts were very very different many of the themes of both the early 20th century and the late 1960/early 1970s were the same same. One thinks in particular of, for example, increasing awareness of human society's impact on the environment and nature, the early 20th century seeing the establishing of the first organic gardening and vegetarian movements, subjects brought to the fore by the 1960s Hippies. Or gender equality, the emancipation movement of the 1960s/70s being mirrored in the early 20th century, a society that although still very patriarchal was starting to move towards at least an acceptance of an understanding of parity, for all that we often make light of the Reform Dress, that ubiquitous component of any progressive Art Nouveauists oeuvre, there was reason such existed, and the early decades of the 20th century also seeing with Gertrud Kleinhempel and Margarete Junge, the first professional female furniture designers.

Yet Art Nouveau, and Luigi Colani are often reduced to, understood as, flowing lines, curves, the florid. A state of affairs which neatly highlights one of the core problems of post-War design, objectification, an understanding of "good design" as based on formal characteristics rather than that which is inherent in the work.

Or put another way. Luigi Colani's above quoted complaint about an "ultra-conservative attitude towards design, which does not yet dare to question Bauhaus", continues, "although Bauhaus itself had questioned everything". And from that questioning arose understandings and formal expressions.

One can, we'd argue, remark similarly on what Ray Eames and Charles Eames, with the tacit support of George Nelson, achieved at Herman Miller in the 1940s and 50s, of what the Italian Radicals of the 1960s and 70s achieved, the Postmodernists of the 1980s, all of whom "questioned everything", and all of whose works, as with those of the inter-War Functionalists, are all too often considered today as templates for design rather than impulses.

And which brings us back to Instagram Luigi Colani. And Art Nouveau, that in context of both one rarely looks beyond the superficial.

Luigi Colani and Art Nouveau is an invitation, an insistence, to do just that.

A bijou exhibition if one that in the reflections, considerations and discussions it encourages and enables has a vista far beyond the actual physical space, Luigi Colani and Art Nouveau, thankfully, features only very little of the automotive design for which Colani is popularly best known. A situation that much as we approve of, we appreciate others will question; but as an exhibition Luigi Colani and Art Nouveau isn't about the objects realised by Luigi Colani but about approaching a more founded appreciation of the ideas, positions, understandings that underscored that work, if one so will, is about the why not the what.

Not that the automobiles are excluded, they're not, they are there, including a bodywork from his 1960 Colani GT and a page from Ylem indicating his very obvious disgust at the private car as a form of urban transport, and which in doing so allows access to the environmental understandings that underscores much of Colani's work, of Luigi Colani's understanding of humans as part of nature rather than masters over nature. And which will also hopefully annoy all those petrol-heads who see Colani as some sort of deity.

But primarily Luigi Colani and Art Nouveau is a discussion undertaken through furniture, a logical basis given that his frustration at the "stupid ... damn stupid" West German furniture industry in many regards is and was the starting point not only for his career as a product designer rather than exclusively an automotive and aircraft designer, but his reflections on the need for a "renaissance of Art Nouveau". And a basis for discussion which allows for a few moments that can be enjoyed independently of the wider discourse and simply as objects in their own right, including, and amongst many others, an outrageous but not indelicately or objectionably so 1979 "Curry Yellow" bathroom sink unit for Villeroy & Boch, his Pool seating landscape for Rosenthal from 1970/71, or his Zocker children's stool and its adult companion, Der Colani, for Kinderlübke and Top System Burkhard Lübke respectively, works which in many regards have their origins pre-Art Nouveau, in Victorian reading chairs, and which are desperately, despairingly crying out for a contemporary re-issue. We hope someone, somewhere is listening to those plaintive appeals.

We never met Luigi Colani, but the impression he gives is very much of someone who wasn't shy in their opinion of themselves, and certainly the marketing of the brand Luigi Colani is every bit as important to the Luigi Colani story as the works; however, the cigars, the provocations, the showmanship, the ego, the question if one would want to have met him, shouldn't be allowed to detract from the works.

Works which as presented in Luigi Colani and Art Nouveau allow for reflections and considerations on not only Luigi Colani's understanding of the world and his understanding of design, or perhaps more accurately put a key, in not necessarily his solitary, singular, understanding of the world, understanding of design, nor only on Luigi Colani's place in the (hi)story of post-War German design, reflections and considerations we'll come back to in a later post, but also reflections and considerations on subjects such as, and amongst others, substantiality through form, the vast majority of Colani's works have barely aged in the decades since their creation and which leads into reflections and considerations on honesty in design, of an object arising from principles and ideals rather than mercantile motivations: reflections and considerations on ergonomics in not just furniture but in context of all our objects of daily use, and the question why so many objects have kept their form for centuries, without that form ever being questioned; reflections and considerations on the use of plastic in furniture design, and, once again, the question if our contemporary plastic problem is plastics fault or ours?; reflections and considerations on the form function relationship, on aesthetics, on functionality, the relationship between object and user, reflections and considerations on Art Nouveau.

And reflections and considerations which allow one to approach an understanding that we needn't necessarily fear a "renaissance of Art Nouveau". But do need to understand what that means.

Luigi Colani and Art Nouveau runs at the Bröhan-Museum, Schlossstraße 1a, 14059 Berlin until Sunday May 30th.

Full details, including information on the accompanying fringe programme can be found at www.broehan-museum.de/luigi-colani-and-art-nouveau

And as ever in these times, if you are planning visiting any exhibition please familiarise yourself in advance with the current ticketing, entry, safety, hygiene, cloakroom, etc rules and systems. And during your visit please stay safe, stay responsible, and above all, stay curious……..

1Luigi Colani at the opening of the exhibition Salon 1900 - Kunst und Gewerbe at Kösters, Münster April 27th 1977, quoted in Peter Dunas, Luigi Colani und die organisch-dynamische Form seit dem Jugendstil, Prestel, München, 1993

2The Luigi Colani biography, certainly his early years is at best sporadically documented, so much so that there is no biography in either Luigi Colani and Art Nouveau the exhibition nor the catalogue. Most sources simply state his date of birth as 1928, the August 2nd reference can be found in Peter Dunas, Luigi Colani und die organisch-dynamische Form seit dem Jugendstil, Prestel, München, 1993.

3The name change came in 1957, allegedly, because all successful designers were Italian..... but it also very neatly underscores the deliberate and intensive marketing of his person, that the brand Luigi Colani is as much a product as any objects he designed.

4Interview with Luigi Colani, Experiment 70. Designvisionen von Luigi Colani und Günter Beltzig, Almut Grunewald and Tobias Hoffmann [Eds.], Museum für Konkrete Kunst Ingolstadt, 2002

5ibid

6This quote is widely attributed to Ettore Sottsass, but we are unaware of its origins or the context in which it was made. We're still looking, and are confident that one day we will find it.....

7Luigi Colani quoted in Peter Dunas, Luigi Colani und die organisch-dynamische Form seit dem Jugendstil, Prestel, München, 1993