smow Blog Design Calendar: April 14th 1874 – Happy Birthday Margarete Junge!

“The work of the Dresden artist Margarete Junge is largely shrouded in darkness” noted the art historian Gert Claußnitzer in his introduction to the 1981 exhibition “Margarete Junge. Fashion sketches and flower studies”1

And while Margarete Junge’s 2D works may have been allowed to shine, if only briefly, in the early 1980s, her 3D works remained stubbornly shrouded: only in recent years being afforded the opportunity, if only partially, to radiate as they once did.

Thankfully. For the works, and the biography, of Margarete Junge are as interesting and important as they are illuminating……

Works by Margarete Junge, as seen at Against Invisibility – Women Designers at the Deutsche Werkstätten Hellerau 1898 to 1938, Kunstgewerbemuseum Dresden 03.11.2018—01.03.2019

Born on April 14th 1874 in Lubań to the watch dealer and manufacturer Johann Bernhard Junge and his wife Octavie, the early biography of Octavie Henriette Margaretha Junge has (largely) remained “shrouded in darkness”: save that (a) shortly after her birth family Junge moved to Dresden,2 and (b) an anecdote that as a young child she realised a particularly accurate and detailed drawing of her mother’s sewing machine.3 As with all such childhood anecdotes a potentially apocryphal recounting, but one which in context of what she later achieved, could also be true; and if true provides an interesting insight into both the development of the young Margarete Junge* and the environment in which she was raised.

The biography of Margarete Junge first becomes much more tangible around 1892 when she began attending classes at Dresden’s Trades’ Draughting School, an institute run by the local Frauen-Erwerbs-Verein and existing very much in context of the increased demand for, and provision of, art and craft education amongst women at that period; and can be firmly anchored in October 1896 when, aged 22, she enrolled in the Künstlerinnnen-Verein Munich’s Women’s Academy,4 at that time one of the principle centres for female artistic education in the future Germany, and where she remained until 1898 before, one presumes, returning to Dresden. What is certain is that after leaving Munich she slips from view. Until 1901 when, and in cooperation with Gertrud Kleinhempel, Margarete Junge was successful in (at least) two competitions, two competitions and two prizes which not only provide a clue** as to how Margarete Junge occupied herself after leaving Munich, but also underscores the close connection between Junge and Kleinhempel: the biographies of the two sharing a common path that begins at the Dresden Trades’ Draughting School and Women’s Academy Munich and which… is a subject for another day.

In May 1901 Junge and Kleinhempel were awarded first prize in a competition organised by the Verein für Dekorative Kunst und Kunstgewerbe Stuttgart in conjunction with the upholsterer Theodor Braun, seeking a design for an upholstered Salon suite comprising a sofa, armchair and side chair, and which was, arguably, more about the material than the furniture, although did, naturally, involve giving form to their furniture; amongst which their armless, highback, sofa strikes us as particularly bold.5 The following month the pair were awarded second prize in a competition to design “a living room that should also serve as a dining room” organised by the Dresdner Werkstätten für Handwerkskunst a.k.a. Deutsche Werkstätten Hellerau, a competition which was very much about furniture and furnishings. And a second prize which saw Margarete Junge invited to join the Dresdner Werkstätten für Handwerkskunst, and thereby the opportunity to earn a living from furniture design. An opportunity Margarete Junge understood to take. And which thanks to the new thinking propagated by the Werkstätten means that however deeply Margarete Junge’s work may have become “shrouded in darkness”, it was, as The Smiths would have it, a light that never went out.

As previously noted in these dispatches: established in 1898 by Karl Schmidt the Dresdner Werkstätten für Handwerkskunst was very much a reform orientated institution, one established with the aim of producing affordable furniture in the evolving reduced, restrained, sachlich, understanding of the period. Aside from formal, ornamental, material and constructional innovations, the Werkstätten also went new, reformed, ways in its relationship with its creatives: not only paying them via a, then novel, licence fee system very similar to that in place in our contemporary furniture industry, but was also one of the first furniture manufacturers to name the individual designers in their catalogues rather than listing works as anonymous in-house creations. And thereby not only underscoring, and for all acknowledging, the creativity of the designer involved and their contribution to the company portfolio, but also allowing the likes of a Margarete Junge a visibility many designers of that period, male and female, are denied now. And were denied then.

Amongst those who noticed Margarete Junge then was Henry van de Velde who in 1902 penned a long text on the Dresdner Werkstätten für Handwerkskunst,6 giving a large part of it over to Margarete Junge and Gertrud Kleinhempel, if with an ever so slightly condescending tone, a tone, arguably, typical of the period, but no less condescending, patronising, for the fact: we are, for example, certain that he would never imply the sketches of a male designer “represent the rooms of their childhood”, that they remind one of “pages from a child’s picture album” and “awaken thoughts of dolls-houses”. He wouldn’t. However he does very neatly, and satisfyingly, employ that tardy analogy as a conceit by which to fulsomely, uncondescendingly, honestly, praise the work of Junge and Kleinhempel. If admittedly he does do his very best to spoil it with passages such as “simplicity, which in the hands of the simple women tends to become a little coarse, expresses itself in the works of Miss Kleinhempel and Miss Junge, sometimes with grandeur, always with dignity”.

That van de Velde was genuinely impressed by what he saw, by that dignified simplicity, tending to be underscored by the fact he commissioned works by Margarete Junge and Gertrud Kleinhempel for 12 of the ca. 30 patients’ bedrooms, and also for the male and female guest reception rooms, of his 1905 sanatorium in Trzebiechów7; albeit not works from the Dresdner Werkstätten für Handwerkskunst but from the Werkstätten für Deutschen Hausrat Theophil Müller.

Established in Dresden in 1902, and in many regards an off-shoot of the Dresdner Werkstätten für Handwerkskunst, the Werkstätten für Deutschen Hausrat, similarly sought to produce affordable, reduced furniture, similarly sought assistance in its aims from Kleinhempel and Junge, similarly named the designers in its catalogues, and similarly concentrated on room ensembles, rather than individual objects per se; and which in concentrating on such allows for a much better insight into Margarete Junge’s understanding of furniture and interior design, allowing us as it does to understand her furniture works in the context in which they were created, in context of other objects in a shared space and the wider relation of the space to the user, which is an important factor in considering early 20th century furniture, in furniture works realised before the age of more conceptual/abstracted design approaches.

And room ensembles which were also the predominant display context of the Art/Applied Art exhibitions that proliferated in the decades of the late 19th/early 20th century, and which helped the light of a Margarete Junge to shine that bit brighter. To shine that bit further. Amongst the first exhibitions at which Margarete Junge was represented one finds important international events such as the 1901 Art Exhibition in Dresden, in many regards her public premiere and where alongside furniture, including a bookcase for a home library designed by Otto Gussmann, she also presented jewellery for the goldsmith Arthur Berger8; the 1902 Prima Esposizione Internazionale d’Arte Decorativa Moderna in Turin, where in addition to furniture and silverware she presented a pendant lamp for K & M Seifert & Co9, a lamp which, if it is the one we believe it is, carries itself with a restraint and florid simplicity many of its contemporaries would have been well advised to follow10; the 1904 World Expo in St Louis, where Junge and Kleinhempel alone represented the Werkstätten für Deutschen Hausrat11; and the 1906 German Applied Arts Exhibition in Dresden12, an exhibition which not only in its focus on applied rather than fine arts helps underscore a tangible shift that was occurring at that period, but which, in effect, confirmed Margarete Junge’s shift from the new face at the 1901 Dresden exhibition to an established designer. A shift underscored by the scale of the room ensembles with which she was entrusted in 1906, as opposed to the elements of rooms she was entrusted with in 1901: specifically a bedroom, largely in maple, and a Gartenzimmer, essentially a conservatory, realised in what the catalogue, and all reports, refer to as “Osagon-Pine”, which could be a wood variety that briefly existed in early 20th century Sachsen, and then vanished without trace. Or could be a misspelling of Oregon pine. And a room whose furnishings, in addition to a not uninteresting looking semi-circular writing table/desk, also included a harmonium for J. T. Müller, and thus both a reminder of the importance, omnipresence, of musical instruments in the well appointed home of the period, and also another string to Margarete Junge’s bow, reed to her harmonium?, certainly an addition to her orchestra of design genres that included lighting, textiles, jewellery, toys, silverware, furniture, rugs, clocks and which following the 1906 exhibition was to become enriched by one more: education.

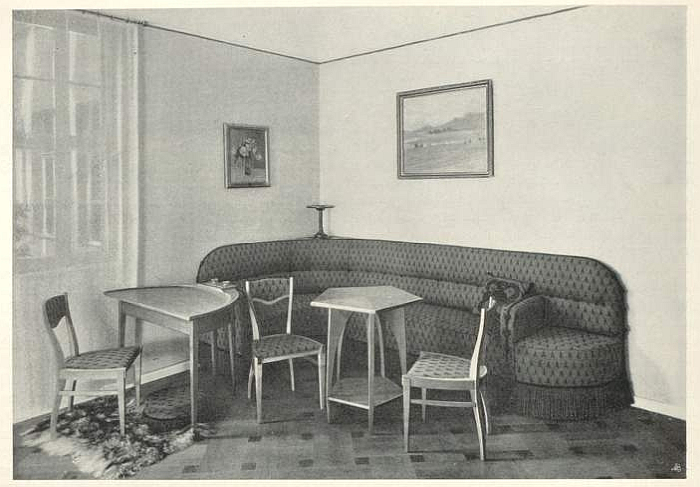

Empfangszimmer (Modell 428) by Margarete Junge for Werkstätten für Deutschen Hausrat Theophil Müller ca. 1905 (Photo © GRASSI Museum für Angewandte Kunst / Christoph Sandig)

In 1907 Dresden’s Kunstgewerbeschule opened a new Schülerinnenabteilung, Female Department, to whose teaching staff Margarete Junge was appointed in June 1907 as lecturer “for designing and executing female artistic handicrafts and clothing, as well as draughting of architectural applied arts”13. And while the inclusion of the term “female artistic handicrafts” does neatly underscore that female freedoms at that time were very much controlled by the prevailing benevolent patriarchy, one must also note that Junge was (a) the only member of the Schülerinnenabteilung staff who taught the execution of projects, which, yes, on the one hand was sewing and embroidery, but on the other was also woodwork, toys, for example, being considered a female artistic handicraft,14 and (b) was the only member of the entire 1907 Dresden teaching staff specifically charged with teaching “draughting of architectural applied arts”.

And while it is unclear what “architectural applied arts” meant in 1907, in 1913, when it was a specialisation of its own, it was the “draughting and designing of objects intended for embellishing buildings”, specifically defining the creation of designs for, and amongst other trades, ornamental metalsmiths, ceramic stove factories and cabinetmakers,15 and as such does allow for the faintest of faint possibilities that Margarete Junge was allowed to teach furniture design. Or at least small items thereof. Sadly records are rare, and one accessible source that could have provided a clue, a 1908 review in the magazine Kunstgewerbeblatt of works by female students at the Kunstgewerbeschule,16 sadly, and utterly inexplicably given its subject matter, couldn’t find space for examples of works by Margarete Junge’s students. Only those of her Schülerinnenabteilung colleagues Max Frey and Erich Kleinhempel, brother of Gertrud. A promise to print examples of Junge’s students works in a later edition, sadly not being kept.

And even if she had been allowed to teach more than female artistic handicrafts, then only briefly: by 1913 Margarete Junge was no longer responsible for “architectural applied arts”, was only responsible for “designing female artistic handicrafts and clothing”. A change which should be understood in context of general developments at the school rather than in any reflection on her work; particularly against the facts that in 1915 gender segregation at the Kunstgewerbeschule ended – one notes some four year before Bauhaus introduced such – and for all that at some point between 1913 and 1925, the exact date being lost in the mists of time and ruins of War, Margarete Junge was raised to the position of Professor, as one of, if not the, first female Professor in an Applied Arts School in Prussia. And a position she held until her enforced retirement at the behest of the NSDAP in 1934; formally “as a consequence of cost-cutting measures”, if suspicions exist that the real reason could be found in her understandings of the world17, for all her understanding of a world of gender equality. One of the many, many things the NSDAP weren’t keen on.

Post-War Margarete Junge kept a small atelier in Dresden-Hellerau, largely spending her time realising, not exclusively, but also, fashion sketches and flower studies, and slowly slipped from popular view. Margarete Junge died in Dresden on April 19th 1966, aged 92.

Gartenzimmer by Margarete Junge for Werkstätten für Deutschen Hausrat Theophil Müller, as presented at the III Deutsche Kunstgewerbeausstellung Dresden 1906 (Photo © Münchener DigitalisierungsZentrum/Bayerischen Staatsbibliothek (BSB))

Margarete Junge wasn’t the only female furniture designer active at the turn of the 19th/20th century, aside from, and staying in a Prussian context, the aforementioned Gertrud Kleinhempel one has the the likes of, and amongst others, Fia Wille who together with her husband Rudolf ran an interior design business in Berlin, for whom she designed furniture, and who was a member of the short-lived, but influential, Werkring collective18; Lilly Reich, who in 1911 was commissioned to furnish 32 rooms in a Jugendheim in Berlin,19 her first step in a still far too poorly understood furniture design career; or Marie Kirschner who was responsible for numerous turn of the century private and public interiors, for numerous articles of, critically well received, furniture and who in her position within the Vereins der Künstlerinnen und Kunstfreundinnen Berlin helped advance the cause of female applied artists, including staging a major showcase of female creatives at the 1904 St Louis exhibition20; however, we’d argue, Margarete Junge does occupy a very special position.***

On the one hand she was a professional furniture and lighting designer, creating works for company catalogues and portfolios, works which it was hoped would attract the attention of, as yet unknown, future, customers; which is a very different undertaking, a very different approach to design, than that of the interior designer tailoring solutions to the preferences and idiosyncrasies of a client, and thus places Margarete Junge very much closer to our contemporary furniture designers than to many of her own contemporaries. And that at a time when furniture design was essentially the preserve of architects: and, one notes, a relatively small group of architects, throughout the first decades of the 20th century one meets the same names over and over and over again. And a circle she established herself in, and with a degree of success; her furniture designs not only being widely exhibited but attracting both interest and customers over a prolonged period.

And on the other hand she was a professional design teacher who taught for 27 years at the Kunstgewerbeschule Dresden, a great many of them as the only female member of staff, and that at a time when despite evolving attitudes, and Great War enforced demographic changes, females weren’t universally accepted in what had been traditional male domains. And also at a time when creative education was undergoing a fundamental transformation, away from more academic traditions to freer expressions, and for all a time when applied arts education was moving from creations for craft to creations for industry, including in the, perceived, female disciplines such as ceramics, toys or textiles.

Thoughts which lead us back into the shadows: for while we may have examples of Margarete Junge’s works and numerous references to Margarete Junge as a designer and teacher, we have but precious few examples of how Margarete Junge viewed, understood, related to the period in which she was actively contributing to design and design education. Or put another way, while we have many of her works**** and most of her biography, her voice is missing.

We know, for example, that in 1907/08 Margarete Junge was one of the first female members of the newly founded Deutsche Werkbund, and that in context of the 1914 Werkbund Exhibition in Cologne was responsible, alongside the weaver and author Oskar Haebler, for the curation of the Textiles section of the Sächsiches Haus21: but did she visit the Werkbund exhibition? What did she make of the from Anna Muthesius and Else Oppler-Legband organised Haus der Frau? What did she make of Else Oppler-Legband’s comment that the Raumkunst, Interiors, section, which took up a good third of the Haus der Frau was, “the most difficult to organise, since interior design is probably the youngest area in which women work independently”?22 Where did she position herself in the Standardisation Debate: on the side of Hermann Muthesius and his demands for standardised forms or with van de Velde and his insistence on the freedom of formal expression?

Beyond the question of standardisation what was her position to the many other fundamental design questions of the day such as ornamentation, machine production, historical archetypes? For Margarete Junge did form follow function? What was her wider position to and influence within the Werkbund? What was her relationship with and thoughts on Peter Behrens, Richard Riemerschmid, Bruno Paul et al? Or Henry van de Velde? How did she respond to his thoughts on her?

Similarly her relationship to and thoughts on Bauhaus, Burg Giebichenstein Halle and the wider developments of artistic and design education in the first third of the 20th century? The evolving methodology and practice of creative education? Such couldn’t have just passed her by. The Kunstgewerbeschule report for the years 1926 to 1930, for example, lists those industrial partners for/with whom the school realised projects, including several which, theoretically, fell into Margarete Junge’s domain,23 but was she active in acquiring them? Did she approve of such cooperations? How much influence did she have on the Kuntsgewerbeschule’s workshops?

Margarete Junge designed and taught design in a period of rapid development of design and design education, yet we currently have little more than a few anecdotes to help place her in that period, to help properly place her on design’s helix. And properly placing her is important not only to better understanding Margarete Junge, but to help us better understand the developments of the period, to developing the more probable understandings of the (hi)story of design we need. It is to be hoped that her voice is hidden in the depths of the archives, in snippets oft skipped over because researchers were on another trail, and because Margarete Junge was “shrouded in darkness”. It is to be hoped…… not least because as one of the first professional female furniture designers and one of the first professional female design educators, Margarete Junge helped illuminate many a path in the early decades of the 20th century, many a path that otherwise could have looked to dark and foreboding to follow, and, we are certain, Margarete Junge could help illuminate many a contemporary and future path. If her light is allowed to fully radiate……

Happy Birthday Margarete Junge!

* As far as we can ascertain she herself long used “Margaretha”, and in the catalogue for the 1906 Dresden exhibition she is also “Margaretha”. Otherwise everyone else used “Margarete”, except the Kunstgewerbeschule who until ca. 1913 went a middle way with “Margarethe”, before dropping the “h” Why the different forms? We no know…but it is, as discussed in the exhibition Against Invisibility, a reason for later invisibility. We use “Margarete” simply because it is the most commonly used form.

** Margarete Junge and Gertrud Kleinhempel, arguably, first became acquainted at the Trades’ Draughting School, and the two were, at least briefly, flatmates in Munich.24 The address given in conjunction with the 1901 Stuttgart competition is that of Gertrud’s mother and her brother, Fritz, in Blasewitz, which is presumably where Gertrud was based. Gertrud, along with her brother Erich, was active with the Dresdner Werkstätten für Handwerkskunst from ca 1899, and so it is not inconceivable that on returning from Munich in 1898 Margarete Junge began cooperating with the Kleinhempels. And the Dresdner Werkstätten für Handwerkskunst. But currently that is no more than a possibility. If a plausible one. Not uninteresting is also the fact that parallel to the Dresdner Werkstätten für Handwerkskunst competition the Dresden carpentry firm Robert Hoffmann also ran a competition, theirs for a Salon. Erich Kleinhempel coming second. And so despite having previously worked with Erich, Gertrud Kleinhempel chose to cooperate with Margarete Junge on the Dresdner Werkstätten für Handwerkskunst’s competition rather than with Erich on the Robert Hoffmann one.

*** The same applies, unquestionably, for Getrud Kleinhempel, who, aside from her work as a designer, took up a teaching post at the Handwerker- und Kunstgewerbeschule Bielefeld in 1907, and was appointed Professor in 1921. Junge and Kleinhempel are, we would argue, very much of equal importance and relevance. However our focus here is clearly Margarete Junge.

**** That we haven’t discussed Margarete Junge’s works in more detail here is solely on account of the current realities: our planned visits to various libraries, archives and museums had to be postponed, and thus so has the discussion. Otherwise it would have been incomplete. However, and in contrast to the unkept 1908 promise of the Kunstgewerbeblatt to publish examples of Junge’s students works at a later date, we will bring it at a later date. Hopefully with more images……

1. Margarete Junge. Modebilder und Blumenstudien, Galerie Kunst der Zeit, Dresden, 1981

2. Johann Bernhard Junge first appears in the Dresden Adressbuch in 1895

3. Natalia Kardinar, Margarete Junge – Künstlerin und Lehrerin, Dresdener Kunstblätter, No. 4, 2003, pages 223 – 226

4. Yvette Deseyve, Ein “ausserordentlich schmiegsam” Talent, in Margarete Junge. Künstlerin und Lehrerin im Aufbruch in die Moderene, Marion Welsch and Jürgen Vietig (Eds.), Sandstein Verlag, Dresden, 2016

5. Verein für Dekorative Kunst und Kunstgewerbe Stuttgart, Mitteilungen Nr 3, 1901, pages 82-88 https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/mvdkk1901/0089/image (accessed 13.04.2020)

6. Henry van de Velde, Werkstätten für Handwerks-kunst, Innendekoration. Mein Heim. Mein Stolz, Vol. 13, Nr. 6, Juni, 1902, page 153ff https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/innendekoration1902/0160/image (accessed 13.04.2020)

7. Antje Neumann and Brigitte Reuter (Eds.), Henry van de Velde in Polen | w Polsce, Deutsches Kulturforum östliches Europa e.V. Potsdam 2007

8. Offizieller Katalog der Internationalen Kunstausstellung Dresden 1901, pages 127, 135

9. see e.g. Johannes Kleinpaul, Das neuzeitliche Kunstgewerbe in Sachsen, Kunstgewerbeblatt Vol 13 Nr, 9 1902, page 165ff

10. Kunst und Handwerk, Vol. 53 Nr. 6, 1902-1903, page 165. We’re not 100% certain that is the lamp that was presented in Turin, but firmly belive it to be

11. Amtlicher Katalog der Ausstellung des Deutschen Reichs / Weltausstellung in St. Louis 1904 page 459

12. Offizieller Katalog, Dritte Deutsche Kunst-Gewerbe-Ausstellung, Dresden, 1906, pages 78, 79, 166 See also e.g. 1906 Erich Haenel, Die dritte Deutsche Kunstgewerbe-Ausstellung Dresden 1906, Dekorative Kunst Vol. 14 Nr 9, 1906 page 481ff; Paul Schumann, Die dritte Deutsche Kunstgewerbeausstellung Dresden 1906, Kunstgewerbeblatt Vol. 17 Nr 11 1905-1906, page 165ff; Ernst Zimmermann, Neugestaltete Klaviere auf der Dresdner Kunstgewerbe-Austellung, Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration, Vol 18 Nr 7, 1906, pages 782 – 785; Ernst Schur, Die Raumkunst in Dresden 1906, Die Rheinlande Vol 12, Nr 8 1906, page 56ff; Gmelin, L., Die Dresdener auf der III. Deutschen Kunstgewerbeaustellung, Kunst und Handwerk, Vol. 57 Nr.2, 1906, page 52ff

13. Bericht über die Königlich-Sächsische Kunstgewerbeschule und das Kunstgewerbemuseum zu Dresden, 1907, page 19

14. Cordula Bischoff, Die erste Frauenklasse der Königlichen-Sächsichen Kunstgewerbeschule Dresden, in Margarete Junge. Künstlerin und Lehrerin im Aufbruch in die Moderene, Marion Welsch and Jürgen Vietig (Eds.), Sandstein Verlag, Dresden, 2016

15. Berichte über die Königlich Sächsische Kunstgewerbeschule und das Kunstgewerbemuseum zu Dresden auf die Schuljahre 1911-1912, 1912-13, page 6

16. Arbeiten der Schülerinnen-Abteilung der köngigl. Kunstgewerbeschule Dresden, Kunstgewerbeblatt Vol, 19, Nr. 11, 1908, page 201ff

17. Marion Welsch, Der Gleichklang unserer Seelen tut uns wohl, in Margarete Junge. Künstlerin und Lehrerin im Aufbruch in die Moderene, Marion Welsch and Jürgen Vietig (Eds.), Sandstein Verlag, Dresden, 2016

18. Corinna Isabel Bauer, Bauhaus- und Tessenow-Schülerinnen. Genderaspekte im Spannungsverhältnis von Tradition und Moderne, PhD Thesis, Universtät Kassel, 2003 https://kobra.uni-kassel.de/handle/123456789/2010090234467 (accessed 13.04.2020)

19. Matilda McQuaid, Lilly Reich: designer and architect, Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1996

20. Amtlicher Katalog der Ausstellung des Deutschen Reichs / Weltausstellung in St. Louis 1904: Full list of the Berlin group presentation page 443 – 445, while page 459 notes Kirschner’s Damensalon.

21. Deutsche Werkbund Ausstellung Cöln 1914, Offizieller Katalog, Reprint Köln. Kunstverein, 1984, page 156/157, 166/167. Judging from the catalogue, Margarete Junge was in all probability only responsible for the handmade textiles….

22. Else Oppler-Legband, Das Haus der Frau auf der Werkbundausstellung, Illustrirte Zeitung, Werkbund Nummer, Band 142, Nr 3699, 21.05.1914, page 18

23. Bericht der Staatl. Akademie für Kunstgewerbe Dresden 1926/1930 Among other companies one finds, for example, Textilefabrik Hartenstein in Plauen, Louis Bahner Strumpffrabrik Oberlungwitz and, Wilhelm Vogel Textilewerke Chemnitz.

24. Yvette Deseyve, Ein “ausserordentlich schmiegsam” Talent, in Margarete Junge. Künstlerin und Lehrerin im Aufbruch in die Moderene, Marion Welsch and Jürgen Vietig (Eds.), Sandstein Verlag, Dresden, 2016

Tagged with: Design Calendar, Deutsche Werkstätten Hellerau, Dresden, Margarete Junge, Werkstätten für Deutschen Hausrat Theophil Müller, Werkstätten für Handwerkskunst