An Easter Egg…… or, A stay at home Eastertide hunt for Arne Jacobsen’s Egg……

The 3316 Easy Chair by Arne Jacobsen a.k.a. The Egg is not only one of the most universally recognised works by Jacobsen, but also one of the most popular representatives of both the lounge chair and also of post-War furniture design. Yet, and as with the Easter egg, the Jacobsen Egg is an object whose simple, inviting charms often hide the much more complex, interesting, informative, instructive, realities of its origin and provenance.

And so in a year when many an Easter egg hunt will be extraordinarily localised, we take you an international hunt for the (hi)story of an egg-straordinary chair……

The 3316 Easy Chair celebrated its public premiere not at Easter, or indeed in Denmark, but on November 7th 1958 in context of the exhibition Formes Scandinaves hosted by the Museum des Arts Décoratifs Paris; one of a myriad international showcases staged in the course of the 1950s and 60s promoting design, craft and applied arts in Scandinavia, international showcases which played an important, arguably the, role in establishing the enduring fascination with design from Scandinavia.

A key component of the Formes Scandinaves exhibition concept was entitled Milieu nordique – Nordic ambience – sound familiar? – and which saw each of the five Nordic nations present a self-initiated room installation: Sweden presenting a theatre foyer with furniture by Bruno Mathsson; Norway recreating the “vestibule of a high mountain hotel”; Iceland “the atmosphere of the museum”; Finland, and pushing national stereotypes as far as they could without breaking them, a sauna anteroom, while Denmark was represented by a presentation of “la chambre d’hôtel moderne” by Professor Arne Jacobsen, the catalogue noting that “this theme is particularly topical because M. Jacobsen is currently leading the construction of a grand hotel in Copenhagen.”1 A helpful snippet of information, and one backed up in the exhibition by a photograph of said hotel, the SAS Royal, a photograph which underscored that the SAS Royal was not only indeed “grand” but also astonishingly modern.

Arne Jacobsen enjoying a conversation with himself in his 3316 Easy Chair (photo © and courtesy Fritz Hansen)

The fact that the Danish authorities choose to give their space in Milieu nordique to the SAS Royal tends to indicate the importance of the project; or perhaps better put tends to indicate the very obvious support it had within those agencies charged with promoting Denmark and Danish design, promoting Denmark through Danish design, in the late 1950s. And that whereas late 1950s Norwegians were to be found in romanticised landscapes and Finns, invariably, in their saunas, late 1950s Denmark was (so the narrative) embracing visions of international modernity, was a land, a people, embracing new technical possibilities, new materials, new aesthetic ideals, the future; and thus the SAS Royal can, in many regards, be considered a 22 floor demonstration of the advanced, open and contemporary nature of Danish society, of late 1950s Denmark as a Milieu international, or more specifically as a Milieu transatlantique.

The comparison of the SAS Royal with Gordon Bunshaft’s Lever House, Mies van der Rohe’s Seagram Building or indeed much of the post-War New York skyscraper architecture, has been made so often we really need not repeat it here, alone we need note that the comparison was deliberate: the SAS Royal was conceived in conjunction with the expansion of the SAS airlines flight programme to North America, and, primarily, as a hotel for international, for all US, guests, something underscored by the fact the lower level annexe to the main tower was intended as an SAS check-in area, while a shuttle bus was on stand-by to ferry SAS hotel guests to their SAS flights; and thus, if you will, the SAS Royal stands, was consciously conceived as, a touch of late 1950s New York in the heart of Copenhagen.

Which obviously possess the question, if Jacobsen’s building was informed by prevailing American understandings, what of the furniture and fittings Jacobsen created for the SAS Royal?

Including his Egg.

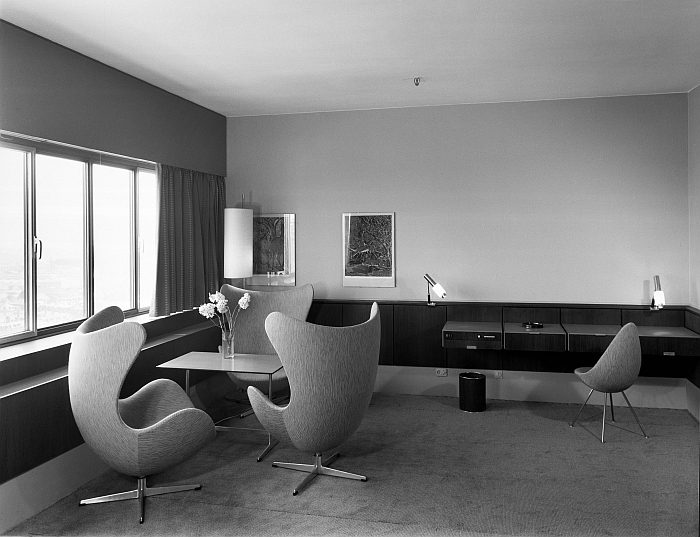

The Egg and Drop chair by Arne Jacobsen in la chambre d’hôtel moderne Copenhagen (photo © Jørgen Strüwing, courtesy Fritz Hansen)

In their fulsome Jacobsen biography, Carsten Thau and Kjeld Vindum discuss the Egg, and its sibling Swan’s, similarities with the “organic” chair designs of Charles & Ray Eames and Eero Saarinen, for all Eero Saarinen’s, noting that in the both the Egg and Swan they see conceptually combined, “the shell of “The Womb” with the pedestal base of “The Tulip.””2 We are in no position to even consider the possibility of potentially contradicting Messrs Thau and Vindum; however, we’d argue that their focus on the “organic” in the Eames and Saarinen’s work is an over analysis of the situation. Why? We’ll get to that, for now we’ll say that, for us, if the Egg has a formal antecedent then it is Jacobsen’s 1955 3107, a.k.a. Series 7, plywood chair for Fritz Hansen, a work that can be considered a flattened Egg. Or the Egg as an inflated 3107. Where we would agree with Thau and Vindum, do see a (more than) obvious conceptual nod to Eero Saarinen and Charles and Ray Eames, is in the act of placing the seat atop a slender metal leg, a construction principle found, for example, in the two year older Eames Lounge Chair*, and which in both objects creates a tension between the exuberantly voluminous seat and the barely there base, and thereby bequeaths both chairs their impression of floating and the association with comfort, ease and luxury. And that arguably more so in the Egg than the Eames thanks to its greater height and improbable four foot base as opposed to the Eames more substantial, almost industrial, five foot base.

The connection that unquestionably can be made between the Egg and works of both Saarinen and the Eames, and where one can also observe the origins of parallel paths to pronounced organic, biomorphic formal expressions, is the central role played by the application of new materials: while the Eames and Saarinen exploited the possibilities of fibreglass to create strident new forms, the Egg relied on styropore. Patented in 1950 by the German chemical conglomerate BASF, styropore’s ready formability allowed it to be used in all manner of products, most popularly for packaging, insulation and, not unamusingly, egg boxes, but not furniture, for which it was not stable, strong, enough; until in 1955 the Norwegian designer Henry W Klein developed a moulding process that allowed styropore to achieve a durability that permitted, actively encouraged, its use in furniture. A process for which Klein received a patent in 1956**, a patent he sold to Fritz Hansen, who subsequently proposed styropore to Jacobsen.

In these pages we’re always (very) quick to highlight a certain unadventurousness, an inherent conservatism, on the part of the Danish furniture industry, the Egg illustrates one of those moments when a manufacturer did take a chance, the reluctance to experiment with the new material and process being much more on the part of the designer: Thau and Vindum note that Jacobsen was initially “more frightened than convinced of the method’s potentials”,3 which we assume is just an unfortunate translation from the original Danish, although there is something endearing in the thought of an Arne Jacobsen being actually “frightened” by an expanded polystyrene. According to Fritz Hansen’s former CEO Peter Lassen, Jacobsen’s distrust, fear, of styropore appears to have been based on the fact styropore is/was, in effect, a material without any inherent properties, it does whatever you want it to, and is thus the opposite of wood where one is naturally limited by the material’s properties, you can only achieve that which it allows, and therefore you are required to work with the wood, engage in a dialogue with the wood, to achieve your required goal. Styropore has no such limitations, you are completely free. And for Jacobsen this seems not to have been such an easy, automatic, transition.

And a situation which reminds us very much of Isamu Noguchi’s comparison of his direct, hands-on, use of material for his sculptures with the indirect casting of bronze or plastic, two materials which, for Noguchi, have, “no particular character. So that those of us who are in a sense wedded to the idea of intrinsic quality residing in the material are suspicious when one starts making things in such an indirect way with materials which in themselves, are supposed to have a kind of quality of being modern.”4

Jacobsen was clearly just as wedded to a material’s intrinsic qualities as Noguchi; however, as Thau and Vindum note, he accepted the challenge, and through doing so discovered that styropore did have a natural limitation: a minimum effective load-bearing thickness. A discovery that must have lightened Jacobsen’s fear, emboldened him. And arguably contributed to his chair’s fearless, figurative Egg form.

But why the figurative Egg form?

Production of the Egg chair at Fritz Hansen in 1963. For all its modernity it is and was a largely handcrafted object (photo © and courtesy Fritz Hansen)

Arne Jacobsen liked eggs?

Certainly the 3316 Easy Chair wasn’t his first egg inspired work, in 1952 Fritz Hansen had released Jacobsen’s 3603 Dining Table, a three-legged object whose table top is formed, tapered, rounded, like an egg. No honest.

The more popular explanation relates the 3316 Easy Chair to a work of sculpture, and, and as is commonly noted in context of the Egg, it was developed via a sculpting process: Jacobsen and the Hungarian sculptor Sandor Perjesi, who at that time was employed by Jacobsen as a model maker, continually reworking a 1:1 model, adding bits, removing bits, readding bits, reremoving bits……….. but then so were all of Jacobsen’s chairs, that was how Arne Jacobsen developed furniture projects, was how all his furniture found their form. And from his earliest, 1920s, furniture works onwards one regularly finds sweeping, organic, curves; the rounded flowing chair, the swelling, arcuate armrest, wasn’t something Jacobsen moved to in the 1950s, wasn’t something informed, far less inspired, by a Saarinen or an Eames, wasn’t a translation of an American idea into Danish: was in many regards inherent in Arne Jacobsen’s understanding of furniture. Was however something he took to a new dimension with the Egg. Arguably having freed himself from his fear of styropore he realised it was a material that could enable him to develop previously unimaginable, unattainable, but possibly envisaged, forms. The Egg is, arguably, the culmination of an ongoing formal experimentation made possible by advances in material technology.

Whereby a not unimportant factor can be found in the much quoted formal tension which unquestionably exists between the quadratic rigidity of the SAS Royal and the free-flowing, biomorphic, softness of the Egg: a tension which, as with the building’s leanings to 1950s American skyscrapers, is deliberate. Is on the one hand a simple, provocative, contrast, and on the other is reflective of that more humane understanding of Modernism as, most popularly, advanced by an Alvar Aalto or a Charles and Ray Eames: many American Modernists, for example, were shocked and appalled that the Eames filled their otherwise textbook Functionalist house in Pacific Palisades with cushions, blankets and objects of folk art. But in doing so they created an inviting domestic interior independent of the clinicalness of the Modernist exterior. Separated the construction principles from the interior design principles without giving preference, priority or primacy to either.

Similarly the Egg brings that touch of comfort, emotion, humanity to an unyielding Modernist construction, without in any way diminishing or admonishing it. And while Jacobsen could, arguably, have achieved the same effect with more traditional wood and upholstery, that wouldn’t have been modern. And late 1950s Denmark was astonishingly modern.

Yeah… but why the figurative Egg form?!?!?

Aside from egg hunts, a popular pastime at Easter is egg rolling……(photo © and courtesy Fritz Hansen)

Some critics see a link to the sculpture of a Hans Arp, a Barbara Hepworth or a Constantin Brancusi, the latter bringing us back to Noguchi, the former to Aalto, while the work Figure (Archaean) by the middlemost stands in the grounds of Jacobsen’s St Catherine’s College campus in Oxford. Others see in its form Jacobsen’s fascination with nature and for all gardens: Arne Jacobsen was not only an avid gardener and designer of gardens but a passionate painter who regularly painted landscapes, gardens and flowers. And so the Egg may not be an egg, but a developing bud, a yet unfurled leave, a seed, and thus placing the 3316 Easy Chair in the abstracted florid of the prevailing Art Nouveau of Jacobsen’s childhood, an exaggerated yet reserved quote on the ubiquitous figurative allia of the early 20th century, and as a Gesamtkünstler Jacobsen was very much an architect/designer in the tradition of that period. Or possibly Arne Jacobsen liked eggs, have you seen his ovate 3603 Dining Table……?

You don’t know why its a figurative Egg do you?

No. But we are very glad it is, because it is the most deliciously logical and satisfying of forms for such an object. In many regards nothing more than a further development of the centuries old wing-backed armchair, Jacobsen’s Egg not only pleasingly rounds that most quadratic of genres, but in doing so enhances and expands the implied simultaneous openness and privacy that is key to such works.

In the SAS Royal Jacobsen’s Eggs stood in the lobby where they not only provided the inhabitant a little seclusion, allowed you to sit without being in full public view, to observe without being observed, unless you wished to be observed in which case you were well framed; but when grouped allowed the creation of a more or less private space, an informal room-within-room, the group being visible and open to one another but (more or less) shielded from the wider lobby. Certainly separate from it. And thus something an object such as, for example, the Eames Lounge Chair wouldn’t, couldn’t manage in such a space.

While in a private space, be that la chambre d’hôtel moderne or a domestic living room, the seclusion and security offered by the Egg is of a much more intimate nature, something perhaps best expressed by John Tenniel in an illustration for Lewis Carroll’s Alice through the looking glass, of Alice curled up in an armchair with her kitten***. Similarly the space and height afforded by the Egg allows one to curl up with a blanket, book, favoured beverage, possibly a kitten, but certainly secluded and shielded from the outside world. An innate, childish, understanding of safety.

And that in an object that exists for itself, free of any functional compulsions, untroubled by formal dogmas, uninterested in stylistic fads, independent of the space it is in, and with a composure and assurance that, and as with an abstract sculpture, it owes alone its formal tensions.

And an object which for all that it, along with its Swan sibling, is singular in Arne Jacobsen’s canon, is also highly representative of that canon: was created, as with almost all Jacobsen’s most enduring furniture designs, in context of an architecture project rather than as a stand alone, contextless, piece of furniture; is an object that suggests a keen observation of how individuals interact with furniture, how furniture interacts with space, and which thus helps individuals to exist in a space; was developed with Fritz Hansen, with whom Jacobsen developed untold projects and a long running relationship which underscores that the designer/manufacturer bond is every bit as important as the author/publisher, musician/record label, artist/gallery bond, in advancing creativity; is international, and for all his association with design from Denmark, Arne Jacobsen was a thoroughly international orientated architect and designer, was arguably as international in his outlook and understanding as his former employee Verner Panton; and is modern, not in the semiotic sense the Danish authorities sought to establish in Paris, but in the sense of being at the forefront of developing technologies, for all developing material technologies, that most important of motors in the development of furniture design. Once one gets over one’s initial fear. Obviously. Which we don’t mean flippantly, those who stay in their comfort zones rarely advance.

And which thus helps underscore that just as our focus shouldn’t be our Easter eggs, but why the Easter egg and what reflections on that Easter egg could possibly teach us; so our focus on the Jacobsen Egg shouldn’t be the Egg itself, but what it can teach us about Arne Jacobsen, about the (hi)story of furniture design, the role of furniture as a cultural good, a cultural mediator, semiotic tool, the necessity to avoid objectifying furniture, and the importance of embracing the new not because its new but because once you understand the new, it can allow you to renew yourself….

Happy Easter!

This year Arne Jacobsen was determined to get a photo of the Easter bunny…… (photo © Jørgen Strüwing, courtesy Fritz Hansen)

* And yes Saarinen’s similarly two year older Tulip chair family also rests on a slender base, but for reasons of readability we only refer to the Eames Lounge Chair

** We haven’t actually seen the patent, the current realities hindering such research, and so aren’t 100% certain of the technical basics of Klein’s invention. But once we have it, we will return to it. And to the, let’s say, issue that appears to have developed between Klein and Jacobsen, see e.g. https://www.vg.no/rampelys/i/ngRdOB/norske-klein-83-la-egget (accessed 09.04.2020) or https://www.dt.no/kultur/eggende-interior/s/2-2.1748-1.3201566 (accessed 09.04.2020).

*** Image is still under copyright and so we can’t post it here, however do a google image search for – John Tenniel Alice through the looking glass chair – and you’ll find it. And understand it.

1. Formes Scandinaves, Musée des arts décoratifs, Palais du Louvre, Pavillon de Marsan, 7.11.1958 – 31.1.1959, Union centrale des arts décoratifs, Paris, 1958

2. Carsten Thau and Kjeld Vindum, Arne Jacobsen, Architektens Forlag, Copenhagen, 2002

4. Isamu Noguchi in conversation with Paul Cummings for the Archives of American Art, Nov. 7 – Dec. 26 1973 https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-isamu-noguchi-11906 (accessed 09.04.2020)

Tagged with: Arne Jacobsen, copenhagen, Easter, Egg Chair, fritz hansen, SAS Royal, swan chair