The so-called Bielefeld Conspiracy asserts that the German city of Bielefeld doesn't exist.

Have you ever been to Bielefeld?, it asks.

Do you know anyone who has ever been to Bielefeld?

Do you know anyone from Bielefeld?

If your answer to all three questions is no........ how do you know Bielefeld exists?

A similar conspiracy could be built around Gertrud Kleinhempel, one of Germany's first professional furniture designers and who for the greater part of her career was active in Bielefeld.

Or was, assuming Bielefeld exists. And assuming Gertrud Kleinhempel exists.

For have you ever seen any work by Gertrud Kleinhempel, do you know anyone who has seen any work by Gertrud Kleinhempel, have you ever seen Gertrud Kleinhempel on the helix of furniture design?

If your answer to all three questions is no........

(The popular narrative has it that) Gertrud Johanna Kleinhempel was born in the village of Schönefeld, a suburb of the contemporary Leipzig, on December 25th 1875 as the youngest of eight children to Amalie and Friedrich Kleinhempel.1

Following the death of Friedrich in 1883 family Kleinhempel moved to Dresden where the young Gertrud attended first the Volksschule and subsequently the Trades’ Draughting School, an institute run by the local Frauen-Erwerbs-Verein and where in 1894 she qualified as an embroiderer and art teacher, before in October 1895 moving to Munich, at that time one of Europe's leading creative and artistic metropoli2, and where she continued her studies, focussing on applied art draughting at the so-called Damen-Akademie, Women’s Academy, an institute run by the Künstlerinnen-Verein München, and at that time one of Europe's leading educational institutes for female creatives.

Gertrud Kleinhempel's enrolment at the Damen-Akademie had been facilitated through a bursary from the publisher3 of the Leipziger Illustrirte Zeitung, and Kleinhempel further financed her studies through both private art tutoring in Munich and Augsburg4, and through illustrations for the magazine Jugend: the publication which gave the highly decorative new Stil of the period its name; a publication to whom Kleinhempel contributed with a varying (ir)regularity between 1897 and 19125, her illustrations reflecting not only the ornamentally florid of Jugend-Stil, but also an increasing rationalisation of that florid over time; and a publication which in the late-19th and early 20th-centuries also featured art works by Richard Riemerschmid, Bruno Paul and Bernhard Pankok, a trio who in the late-19th and early 20th-centuries were amongst the leading figures in the move by artists in the German Reich away from 2D art to 3D applied art, for all from art to furniture, not least through their associations with the 1898 established Vereinigte Werkstätten für Kunst im Handwerk München.

And a move from 2D to 3D, from art to furniture, that Gertrud Kleinhempel made, more or less, simultaneously.

If in Dresden rather than Munich.

Exactly when Gertrud Kleinhempel returned to Dresden is lost in the mists of time; however, that she contributed three illustrations for the Festzeitung6 for a costume ball organised by the Künstlerinnen-Verein in February 1899 to celebrate the opening of their new meeting rooms and atelier space, tends one to the assumption that she was still in Munich in February 1899.

What is much clearer is that in September 1899 "Gertrud Kleinhempel - Dresden" received an Honorary Mention in a wallpaper competition organised by the magazine Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration7, and that in November 1899 Gertrud Kleinhempel made her public debut as a furniture designer, and that in Dresden and in cooperation with a manufacturer with whom she would become closely associated: the Dresdner Werkstätten für Handwerkskunst a.k.a. the Deutsche Werkstätten Hellerau

As oft noted in these dispatches, the Deutsche Werkstätten Hellerau was established in Dresden in October 1898 by Karl Schmidt with the aim, as Schmidt phrased it, "to produce affordable, simple but artistically formed everyday objects"8, and thus very much in keeping not only with evolving understandings of the necessity of a move away from the heavily ornate of previous generations to more rational formal expressions, but also with an understanding of the necessity of supplying well made, high quality, furniture at affordable prices for a mass public. The latter in many regards juxtaposed the Dresden Werkstätten with the Munich Werkstätten who may have been about formal reduction, but were still very much about exclusive works for wealthy clients. At least initially.

The Deutsche Werkstätten Hellerau made their public debut, when albeit in a limited manner, in April 1899 at the Deutsche Kunstausstellung in Dresden, essentially a fine art exhibition but which, and as was becoming customary at that time, also featured applied and decorative arts; and subsequently, and in a much more expansive fashion, in many regards their real debut, in November 1899 at the Volksthümliche Ausstellung für Haus und Herd, Exhibition of Folk Art for Hearth and Home, also in Dresden; an event which although did by all accounts feature examples of rustic, picturesque, romanticised furniture, also had a focus on the provision of furniture and furnishings for less well off sections of urban society, as it were a contemporary folk art, and something which, as the art historian Dr Ernst Zimmermann noted, "thus far has not really existed anywhere - one has barely got beyond theoretical considerations and very isolated attempts - thus one has to first create such an art as if from thin air", and to that very purpose the exhibition's organisers, so Zimmermann, "made use of the thoroughly modern means of a competition"9; specifically a competition for furniture and furnishings for a living room, bedroom and kitchen costing no more the 750 Mark.10 A price that Zimmermann considered still too expensive for the very poorest, at best affordable for the developing middle class; but also noting that such a price was much cheaper than that for which most carpenters would have been able to supply the same objects, to the same quality: machine production was starting to arrive, and with it quality, durable, furniture was becoming more affordable, furniture was becoming more democratic.11

The Deutsche Werkstätten Hellerau were very much at the forefront of such a shift, were very much driving such a movement, and were represented in the Volksthümliche Ausstellung für Haus und Herd competition with two proposals: one from from the goldsmith, sculptor and future Director of the Kunstgewerbeschule Dresden, Karl Gross, and one from Gertrud and Erich Kleinhempel, Erich being the elder brother of Gertrud.

Exactly when Gertrud Kleinhempel draughted her first furniture designs is, as with so much, lost in the mists of time, but one presumes in Munich where she was not only studying applied art draughting but on the Künstlerinnen-Verein applied art jury12, and where she would also have been exposed to events such as the 1897 Internationalen Kunstausstellung staged in Munich's famed Glaspalast and which marked the first public presentation of furniture by those artists who would become associated with Vereinigte Werkstätten für Kunst im Handwerk München: and thus, one presumes, a tendency and development that was tangible in the air in late 19th century Munich and which, arguably, led Kleinhempel to develop her first furniture draughts.13

Alone we can be certain that the Kleinhempels' proposal didn't win the 1899 competition, that honour going to the Dresden architects Georg Heinsius von Mayenburg and Theodor Lehnert14, but does appear to have won a majority of the critical praise; Ernst Zimmermann noting that, "the most original and artistically finest furniture was exhibited by husband and wife Erich and Gertrud Kleinhempel"15, an apparently regular confusion which, apparently, occasionally left Gertrud unmentioned, she being, after all, but the wife of a husband. Which for all our sarcasm is an important point in considerations on the visibility, or not, of female creatives from generations past, wives were often just that, no more, and thus not always worthy of mention16, Zimmermann continuing that, "they are simple, solid, calm, elegant and distinctive, all properties that our furniture has largely had to do without until now, and at the same time appear very practical in that they make good use of the space", and that while ornamentation was absent, "tedium is avoided by emphasising the construction, the clear structuring, as well as by the powerful, slightly curved corner supports and posts, something typical of Rococo, and which defines the character of this furniture", and that "amongst the kitchen furniture, the yellow stained kitchen cabinet is particularly noteworthy on account of its simple yet original design."17

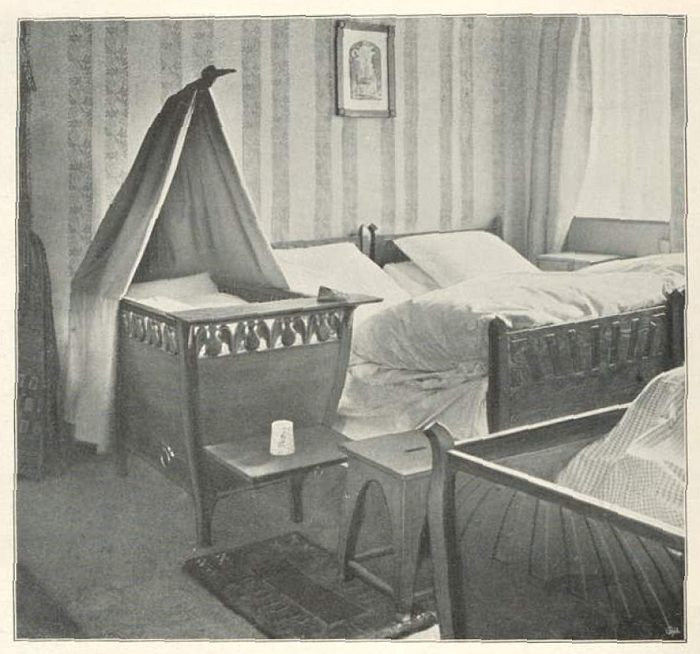

And while Carl Meissner couldn't find much love for the "uniform, glossy bright yellow stain" of the kitchen furniture, the objects themselves he considered veritable "stimuli for the eye". As he did the Kleinhempel's bedroom ensemble, a composition he is at pains to note is "mainly [Gertrud's] hand and not that of her brother", and so getting the relationship correct, and for all finding praise for the cot with its many animal motifs and the "practical perpendicular boards at the foot end", two small shelves for parents/carers to place things on while tending to the child, and which he pronounced not only "delightful" but "a piece of furniture that is formed out of its purpose".18

Similarly formed out of the purpose were, arguably, "the two pieces of furniture that are practically designed as a chest of drawers in the lower section with a desk on top"19, a two in one, space saving furniture, of the type a more cramped flat requires, and which was a fusion that was, apparently, still relatively new for the period, certainly for Paul Schumann who called them, "quirky", in a positive sense, and generally opining that "the Dresdner Werkstätten für Handwerkskunst Schmidt und Müller presented the best work in the exhibition", and that with their presentation they had, "unequivocally proven that affordability and artistically pleasing are compatible."20

And lest we forget, for it is not irrelevant, when the Volksthümliche Ausstellung für Haus und Herd opened in November 1899, Gertrud Kleinhempel was still just 23. Erich was already all of 25.

Fired by the success of the Volksthümliche Ausstellung für Haus und Herd Karl Schmidt decided to move on from presenting room ensembles in abstract contexts and present houses with furnished rooms, room ensembles in concrete contexts, an idea no doubt inspired by the, then still in development, Artists Colony Darmstadt; and an idea he sought to realise through constructing, in context of the 1901 Internationalen Kunstausstellung Dresden, a model village with a range of public, commercial and domestic buildings and for which in 1900 he prepared a plan featuring over 20 creatives and their appointed works. And at the top of the list one finds "G. Kleinhempel, Dresden: Villa, all furnishings". Elsewhere on the list one finds names such as Richard Riemerschmid, Joseph Maria Olbrich and Bernhard Pankok.21

If Karl Schmidt intended that Gertrud Kleinhempel should be responsible for the villa and the furnishings or just the furnishings isn't clear, or at least not from the documentation we have seen; however, even if just the furnishings, the fact that Karl Schmidt considered the then still only 24 year old Gertrud Kleinhempel qualified, capable, desirable, for and of such a project speaking volumes for the regard he obviously had for her talents; while the names one doesn't find on the list, those male contemporaries Kleinhempel was selected above, was preferred above, and Schmidt's list implying high ambition, being an even more voluminous statement. And thus it is all the more regrettable that the project was never realised. Especially if Kleinhempel was to be invited to design and develop the villa itself.

From a such grand plan the Deutsche Werkstätten Hellerau however found itself restricted at the 1901 exhibition to a single room installation: a combined living and dining room by Johann Emil Schaudt, a composition which had been realised after winning the manufacturer's thoroughly modern competition.

Second place in the competition being awarded to Gertrud Kleinhempel and Margarete Junge.22

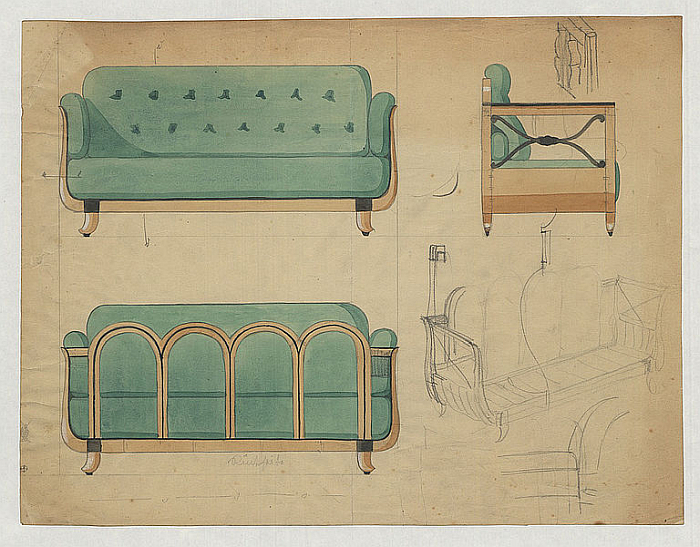

As previously noted, Gertrud Kleinhempel and the year older Margarete Junge share a common educational biography that passes over the Dresden Trades’ Draughting School and Damen-Akademie Munich, and began cooperating at some point around 1900: their first confirmed joint project being in context of a 1901 competition for an upholstered Salon suite comprising a sofa, armchair and side chair, and which was largely about the textile covers rather than the furniture, if the Junge/Kleinhempel sofa is a joyously engaging and pleasingly confusing armless scallop of a work.23 Their first public cooperation being the 1901 Deutsche Werkstätten Hellerau competition; and while they may not have won, they obviously impressed Kurt Schmidt, for parallel to the official exhibition the Deutsche Werkstätten Hellerau presented three room ensembles by Kleinhempel and Junge in the Kunstsalon Emil Richter, an institution which was an important mediator in contemporary art in Dresden at the turn of the century, who would be influential in the establishment of Die Brücke collective and thereby of Dresden's reputation as a centre for expressionist and abstract art, and thus a not irrelevant address for such a presentation; and a presentation which Ernst Zimmermann considered pleasingly "devoid of all exhibition originality, thoroughly robust products of the modern trend" and in being such very neatly reflected for Zimmermann the Werkstätten's focus on "simplicity and solidity, on an artistic impression that primarily arises from the quality of the material as well as the construction", and that amongst the numerous creatives with whom the Deutsche Werkstätten Hellerau cooperated "Fräulein Kleinhempel and Fräulein Junge, have settled assuredly in this aspect of the company".24

And settled not just in the Deutsche Werkstätten Hellerau.

Or just in Dresden.

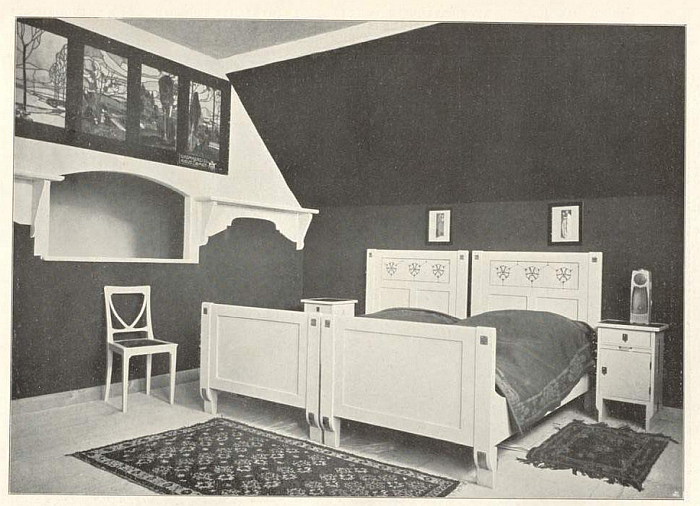

In 1902 Turin hosted the Prima Esposizione Internazionale d’Arte Decorativa Moderna, one of numerous exhibitions of the developing understandings of art and design at the turn of the century which were important in the mediation and dissemination of that which would become popularly known as Art Nouveau, or Arts Nouveau there being varying regional dialects; an event which attracted some of the leading international practitioners including, and amongst many, many, others, Peter Behrens, Victor Horta, or Charles Rennie and Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh; and an event at which the Kleinhempel siblings, in effect, squatted, the presentation of the Munich creatives. Or as Dr. Johannes Kleinpaul phrased it, in the Munich House "two attic rooms were apparently too insignificant and too small for the Munich artists. The rooms were left empty".25 The Kleinhempel siblings took them on and, in conjunction with the Deutsche Werkstätten Hellerau, furnished them: Gertrud creating a bedroom, Erich a so-called bachelor's room, and that in manner, in a simplicity and formal restraint that juxtaposed all to symbolically with the much more decorative and ornate rooms by Bruno Paul, Bernhard Pankok, et al downstairs. Erich Kleinhempel winning a silver medal for his. Gertrud apparently being left empty handed26, if with a further enhanced, and now international, reputation for developing simple, affordable, furniture designed for use not for representation.

1902 also seeing the establishment in Dresden of the Werkstätten für Deutschen Hausrat Theophil Müller, a manufacturer with a focus, as with Deutsche Werkstätten Hellerau, on the affordable, formally reduced yet functionally appropriate furniture that was, not least through the efforts of the Deutsche Werkstätten Hellerau, both increasingly in demand, and increasingly understood as necessary and relevant; and a manufacturer for whom Gertrud Kleinhempel and Margarete Junge quickly became two of the most important designers, creating, individually rather than in cooperation, numerous room ensembles, at the time a popular manner in which furniture was consumed. Again, and so oft, the why Kleinhempel and Junge, apparently, so readily switched from the Deutsche Werkstätten Hellerau to the Deutschen Hausrat Theophil Müller is lost in the mists of time, what we can be more certain of is how in context of their cooperation with Deutschen Hausrat Theophil Müller both Kleinhempel and Junge moved increasingly to ever simpler designs, ever simpler in terms of form, construction, materials and decoration27, and that Kleinhempel and Junge alone represented Deutschen Hausrat Theophil Müller at the 1904 World Expo in St Louis.28 A further international feather in their caps.

And gained further domestic feathers at the 1906 Deutsche Kunstgewerbeausstellung in Dresden, an event which not only underscored Dresden's ever greater importance as a centre for art and applied art in the early years of the 20th century, nor only the rapid development in understandings of furniture and furnishings in the five short years since the 1901 Dresden exhibition, but also tending to confirm both Margarete Junge and Gertrud Kleinhempel's prominent place in contemporary German furniture design.

Gertrud Kleinhempel presenting a dining room in elm and a "sales room for exclusive women's fashions", and thus a commercial and a domestic interior, for Deutschen Hausrat Theophil Müller, in addition to an unrecorded number and variety of carved wooden toys and other small objects for both Deutschen Hausrat Theophil Müller and C. Bühner, Empferthausen, and also a bathroom ensemble for the Meissen based ceramics manufacturer Ernst Teichert. A bathroom that also featured a woven wicker bench designed by Kleinhempel for Theodor Reimann's Fabrik für kunstegwerbeliche Korbmöbel29, a company established in Dresden-Neustadt in 1900, who fashioned themselves in the 1906 catalogue as Hoflieferant, Purveyor to the Court, and who alongside Gertrud Kleinhempel also cooperated with the likes of Richard Riemerschmid and Bruno Paul, thus tending to further underscoring that Gertrud Kleinhempel was very much a furniture designer in and off her time.30

1906 also brings us to Bielefeld.

Or would, if Bielefeld existed.

Following her return to Dresden from Munich in ca 1899, Gertrud Kleinhempel, together with her brothers Erich and Fritz, established a private arts and crafts school in the city, one of innumerable private initiatives at that time which sought to meet the growing demand for creative education and training, and for all an increasing demand amongst females: arts and crafts being one of the few "industries" open to females, albeit females who were denied access to training and education at the publicly funded schools and colleges. And an institution which although it enjoyed a degree of critical success, was, as best we can ascertain, less successful financially. Does however represent that start of both Erich and Gertrud Kleinhempel's teaching careers. Erich's taking him over the Kunstgewerbeschule Dresden to the Kunstgewerbeschule Bremen where between 1912 and 1934 he served as Director.

Gertrud's taking her to Bielefeld.

Specifically the newly established Handwerker- und Kunstgewerbeschule, an institute whose founding director was the architect Wilhelm Thiele, a graduate of the Kunstgewerbeschule Dresden, who had realised a number of cooperations with the Deutsche Werkstätten Hellerau, and who thus was, if one so will, a colleague of Kleinhempel's; and with whom Gertrud Kleinhempel signed an Einstellungsvertrag, a pre-contract contract, on December 23rd 1906 for a position teaching the "Day class for general instruction" and "Textile professions".31

And whereas through her training, private tutoring and private school operation, Gertrud Kleinhempel was well versed in "general instruction", as Claudia Gottfried pertinently flags up, until her arrival in Bielefeld Gertrud Kleinhempel had had next to no practical experience in textiles.32 While she may have formally, nominally?, undertaken embroidery studies as a teenger in Dresden, furniture and interior architecture was unquestionably Gertrud Kleinhempel's specialisation. However, in the early years of the 20th century when females taught in applied arts colleges, they taught textiles, and that, largely, primarily, because in the early years of the 20th century when females taught in applied arts colleges, they taught exclusively female students. And because textiles was one of the first applied art subjects females could study at publicly funded institutions, as they slowly opened up to female students at the turn of the centuries, textile tutors were invariably female. And equally invariably the only females on the staff.

Which poses the question, why did Gertrud Kleinhempel accept the offer? Why not stay in Dresden and design furniture?

We no know, only Gertrud Kleinhempel knows for certain; however, then, as now, for many freelance designers, as Kleinhempel was in Dresden, cooperating as she did with a range of manufactures over a range of genres, a teaching position was/is an attractive option to not only secure up the irregular and unreliable income from freelance design, but also of establishing a pension, and thereby securing your old age. And given that Kleinhempel would have known she would never be offered a furniture design teaching position, she, arguably, decided to accept the offer from Bielefeld.

Possibly also because for all that today Bielefeld is a theoretical location in north-west Germany, then it was a leading centre in the Germanic textile industry, for all the linen industry, a tradition in textile production that goes back centuries and first reached a wider fame and importance in the days of Hanseatic League. And a textile industry that for Gertrud Kleinhempel, may, have provided an impetus beyond the school; if one so will, if I must take a job teaching textiles, then at least in a major textile centre where we can meaningfully link theory and practice. And there certainly appears to have been a goodly amount of cooperation between the school and the local industry.33

And also interest from outwith, most notably from Karl Ernst Osthaus, and important motor in the dissemination of new understandings of form, function, ornamentation, materials et al in the early 20th century and who in 1909 established the so-called Deutsches Museum für Kunst in Handel und Gewerbe which organised travelling exhibitions of what were considered particularly exemplary models for contemporary production, and whose collection includes numerous works by both Kleinhempel and her students. In addition, and in a similar context, Gertrud Kleinhempel was a member of the Oberausschuss, Upper Committee, of the so-called Warenbuch published in 1915 by the Dürerbund-Werkbund-Genossenschaft, an early consummer purchase advice platform, and which awarded a quality mark to products it considered "functional, tasteful and well designed", and sought thereby "to promote the dissemination of good objects of daily use that are simple, appropriate to the material, clear in form, technically good, functional and tasteful."34

The Oberausschuss being the body responsible for final decisions when the numerous selection committees were split; an Oberausschuss on which Gertrud Kleinhempel served alongside the likes of, and amongst others, Hermann Muthesius, Josef Hoffmann or Peter Behrens, and whose members "with their names vouch for the objectiveness and moral cleanliness of the decisions".35

Although textiles and her students were Gertrud Kleinhempel's primary focus in Bielefeld, they weren't her only, and in addition to realising a number of illustration commissions, and continuing to contribute (ir)regulary to Jugend, she also realised a number of furniture commissions, including a director's office for (possibly) the Baer & Rempel sewing machine company36, an executive boardroom for the Kölner Frauenclub at the 1914 Werkbund exhibition in Cologne37 and the living and reception rooms of a villa built by her Handwerker- und Kunstgewerbeschule colleague Richard Wörnle for the textile tycoon Gustav Windel, the latter commission representing her last recorded furniture project.38

And was also kept busy by ongoing wranglings with the authorities.

On her arrival in Bielefeld Gertrud Kleinhempel was initially only given a temporary contract, as Claudia Gottfried notes no reason why was given, but one must assume her gender played a not insignificant role; and it wasn't until 1911 that Wilhelm Thiele was able to persuade the authorities to employ her on a permanent contract, a contract which commenced on April 1st 1911.39 Whereby the April Fool being that although contracted for the same hours as her male colleagues, Gertrud Kleinhempel only received around half the pay.40 A situation that remained until 1921.

The same year in which Gertrud Kleinhempel was raised to the position of Professor, the first female in a Prussian applied arts college to achieve such a position, and possibly the first female in the contemporary Germany. At some point between 1913 and 1925, most probably towards the end of that range, Margarete Junge was also appointed a Professor at the Kunstgewerbeschule Dresden. History has forgotten who was first. Not that it matters, all that matters is that it is remembered that both were. And remembered that had they been male they would both have been Professors much, much, much, earlier.

On April 1st 1938 Gertrud Kleinhempel retired from her position in Bielefeld, aged 62 and after some 31 years, half a lifetime, at the Handwerker- und Kunstgewerbeschule; the local paper noting that, "her departure from the Handwerkerschule means a painful loss for the institute, a loss which is all the greater as Kleinhempel's artistic momentum has by no means flagged".41

Her personal momentum was obviously still equally strong and took Gertrud Kleinhempel in 1939 north to Baltic See coast and the village of Althagen on the Fischland-Darß-Zingst peninsula, and where she lived out her retirement; if an all to brief retirement, Gertrud Kleinhempel passing away in Althagen on February 29th 1948, aged 72.

Since when its been relatively quiet around Gertrud Kleinhempel.

One could say, it's almost as if she didn't exist.

Bielefeld does exist.

We've been there, we know people who've been there, we know people from there. Bielefeld exists.

And Gertrud Kleinhempel?

That between 1875 and 1948 she was physically amongst us, sure. But in the (hi)story of furniture design?

Arguably not.

Which is wrong, not least because, and as with Margarete Junge, Gertrud Kleinhempel is of great importance and relevance to the development of both furniture design and design in Germany. The calls for form to follow function, and for formally reduced, practical, affordable objects of daily use, that rang through the inter-War years, and continue to be so important to understandings of design today, didn't arise in the inter-War years, but were part of a longer process of evolution and development; a process that began in the late 19th century, and a process in which Gertrud Kleinhempel was an important early protagonist. Through both the works she realised, for all the positions and understandings embodied in those works, and also her contribution to the early success of the Deutsche Werkstätten Hellerau and the Deutschen Hausrat Theophil Müller, and thus the popular dissemination of such positions and understandings, Gertrud Kleinhempel helped advance and establish new perspectives on and understandings of furniture, and thereby helped nurture the evolution and development of furniture design. An evolution and development that because it is ongoing continues to influence us today.

And so why is Gertrud Kleinhempel absent today?

Part of the reason is arguably that the greater part of her active furniture design career was before the Great War, a time before (hi)story and which in context of design, certainly furniture design, is continually overshadowed by inter-War developments. And that oblivious of the fact the inter-War developments were heavily dependent on those earlier developments, the inter-War developments didn't arise from thin air, that was the achievement of pre-Great War designers. And also, arguably, because Gertrud Kleinhempel died in a period when design history and the cultural study of furniture was one of the least important considerations in Europe; and a period of geopolitical upheaval in Germany which meant that following her death Gertrud Kleinhempel's German biography would become a split East German:West German biography. And thus almost unresearchable in its entirety until the 1990s.

By which point Gertrud Kleinhempel was as visible as Bielefeld.

And also because, and as with Margarete Junge, she left next to no known written legacy. There are essentially no known texts from Gertrud Kleinhempel, no essays, no letters, no diarys, no etcs, and so we don't know how and what she thought. We could quote verbatim our previous comments on Margarete Junge and her lack of texts, but will restrict ourselves to the observation that Gertrud Kleinhempel contributed not only to the development of design in the first half of the 20th century, but was active as a design educator in one of the more important and interesting periods in the (hi)story of design education, certainly in Germany; yet we don't know how she viewed the world around her, don't know how she understood contemporary developments, what she considered positive, what she considered negative, what she sought to promote, what she thought to restrict, how fair she considered the society in which she lived, how she was received be her male contemporaries, how she received her male contemporaries, far less why she designed as she did. As with Margarete Junge the hope is that the texts, the thoughts, are out there is some archive, but have continually been over read by researchers on other trails.

Because those thoughts, understandings and positions are important to completing our understanding of Gertrud Kleinhempel.

And which is important, not just because Gertrud Kleinhempel was one of the earliest professional furniture designers, someone designing for a manufacturer's portfolio, designing objects for the anonymous mass market, for an unknown future customer, rather than as the Gesamtkunstwerk orientated architect working in context of a specific project and client, or the self-producing carpenter of yore. But also the fact Gertrud Kleinhempel became such as a female. That she started out on a path so typical for many a late-19th century female hoping to have a career in the creative industries, but then left that path and starting forging a new path for herself, a path that itself was new, was not yet gendered.42 Before ending up on the textile path that, so it seems, history has reserved for female designers. Or how do you view the contemporary furniture industry?

And how would you view the contemporary furniture industry if Gertrud Kleinhempel existed?

That Gertrud Kleinhempel doesn't exist isn't a conspiracy, honestly its not; rather it is a symptom of a popular unquestioning acceptance of the (hi)story of furniture design, of a malady that has beset the (hi)story of furniture design. And thus, and as with all symptoms, an indication of an underlying problem, an underlying harmful condition, an admonishment on us all to question that popular (hi)story. And for all to question the popular (his)story.

And thus while the question of Bielefeld's existence is largely one of a theoretical, academic nature, the question of Gertrud Kleinhempel's existence is much more material and acute. For while (hi)story does lose sight of male designers, Erich Kleinhempel being here a most pertinent example43, the loss of one early 20th century male designer amongst many leads to but an incomplete (hi)story of the development of design; the loss of one early 20th century female designer amongst very few, fundamentally skews that (hi)story. And a skewed (hi)story is never the best basis for the future.

Correcting that (hi)story requires the unquestioned and universally acknowledged existence of Gertrud Kleinhempel on the helix of furniture design.

Happy Birthday Gertrud Kleinhempel!!

1see Gerhard Renda [Ed.] Gertrud Kleinhempel 1875 - 1948. Künstlerin zwischen Jugendstil und Moderne, Verlag für Regionalgeschichte, Bielefeld, 1998

2As ever we know metropoli isn't the plural of metropolis, passionately believe it should be and thus feel ourselves empowered to use it

3see Künstlerin und Erzieherin. Frau Professor Kleinhempel tritt in den Ruhestand, Westfällischen Neuesten Nachrichten, Bielefelder Stadtanzeiger, Mittwoch 13. April 1938, available via https://zeitpunkt.nrw/ulbms/periodical/zoom/4697101 (accessed 24.12.2020) The reference is to the "Mitinhaberin", the female co-owner, and an individual who under the current realities we have been unable to identity, but would, we feel, be important to know, as if a bursary was granted to Gertrud Kleinhempel then arguably so were other bursaries conferred.

4ibid

5see https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/jugend?navmode=fulltextsearch&action=fulltextsearch&ft_query=Kleinhempel (accessed 24.12.2020)

6see https://daten.digitale-sammlungen.de/0010/bsb00104499/images/index.html?id=00104499&groesser=&fip=193.174.98.30&no=&seite=1 Bildnr. 5, 17 & 24 (accessed 24.12.2020)

7Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration, Vol III, Nr 2 November 1899 page 92 The competition had been launched in October 1898 and the jury met on 5th September 1899. When Gertrud Kleinhempel submitted her application is unknown, other than between October 1898 and August 1899. And that she submitted it from Dresden. Erich Kleinhempel was awarded one of three third prizes.

8see Ankündigungsschreiben der Dresdener Werkstätte für Handwerkskunst Schmidt und Engelbrecht 1898, reproduced in Klaus-Peter Arnold, Von Sofakissen um Städtbau. Die Geschichte der deutschen Werkstätten und der GArtenstadt Hellerau, Verlag der Kunst, Dresden, Basel 1993, page 20

9Dr. Ernst Zimmermann, Die volksthümliche Ausstellung für Haus und Herd in Dresden, Kunst und Handwerk, Vol. 50 Nr 5 pages 145

10Paul Schumann, Volksthümliche Ausstellung für Haus und Herd in Dresden II Dekorative Kunst, illustrierte Zeitschrift für angewandte Kunst, Band 5, 1900, page 212

11At such moments we always feel a need to point out that Thonet's chairs were cheap and democratic, and before machine production. And also produced in a manner that did away with qualified carpenters. And thus how joyously Thonet fit into the (hi)story of furniture design i.e. they don't.

12Yvette Deseyve, Ein “ausserordentlich schmiegsam” Talent, in Margarete Junge. Künstlerin und Lehrerin im Aufbruch in die Moderene, Marion Welsch and Jürgen Vietig (Eds.), Sandstein Verlag, Dresden, 2016 page 16

13Erich's' early biography is every bit as sketchy as his sister's, and thus where and when he first moved from art to furniture is unclear. Clear is that Erich presented furniture for Deutsche Werkstätten Hellerau at the 1899 Dresden Kunstaustellung, the company's formal debut, see https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/dkd1899/0233 and subsequent photos and text

14Dr. Ernst Zimmermann, Die volksthümliche Ausstellung für Haus und Herd in Dresden, Kunst und Handwerk, Vol. 50 Nr 5 pages 149 available via https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/kuh1899_1900/0164 (accessed 24.12.2020)

15ibid page 151

16A further problem is that one occasionally finds works attributed to "Kleinhempel", and while the norm of the period would be to always give a forename to a female but only use the surname of a male, mistakes were often generally made in attributing: While if the female was considered supplementary by the author then the reference would, invariably, only be the the male, despite the joint nature of the project. And we'd also note that, for example, Ray Eames was barely mentioned until the release of the eponymous Lounge Chair in 1956, for a decade all Eames furniture being popularly understood as the work of Charles Eames alone. We could also mention Aino Aalto, Kajsa Strinning, Lilly Reich... you get the idea......

17Dr. Ernst Zimmermann, Die volksthümliche Ausstellung für Haus und Herd in Dresden, Kunst und Handwerk, Vol. 50 Nr 5 pages 151-152

18Carl Meissner, Deutsche Volkskunst auf der volksthümlichen Austellung für "Haus und Herd" (Dezember 1899) in Dresden, Innen-Dekoration Mein Heim Mein Stolz, Vol, XI, Februar 1900 page 32-33 Available via https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/innendekoration1900/0041 (accessed 24.12.2020)

19Paul Schumann, Volksthümliche Ausstellung für Haus und Herd in Dresden. Dekorative Kunst, illustrierte Zeitschrift für angewandte Kunst, Band 5, 1900, page 136

20ibid

21see "Vorschlag für die Beteilugung des Kustgewerbes an der Deutschen Kunstausstellung 1901 in Dresden" reproduced in Klaus-Peter Arnold, Von Sofakissen um Städtbau. Die Geschichte der deutschen Werkstätten und der Gartenstadt Hellerau, Verlag der Kunst, Dresden, Basel 1993, page 42

22see Kleine Mitteilungen, Kunstgewerbeblatt, Vol 12, page 115

23see Verein für Dekorative Kunst und Kunstgewerbe Stuttgart, Mitteilungen Nr 3, 1901, pages 82-88 https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/mvdkk1901/0089/image (accessed 24.12.2020)

24Dr. Ernst Zimmermann, Sammlungen und Ausstellungen. Dresden. Kunstchronik: Wochenschrift für Kunst und Kunstgewerbe, Vol. XIII, Nr.5, November 14th 1901 pages 77-78

25Dr. Johannes Kleinpaul, Das neuzeitliche Kunstgewerbe in Sachsen, Kunstgewerbeblatt Vol 13 Nr, 9 1902, page 168

26Kleine Nachrichten, Kunst und Handwerk, Vol 53 1902/1903 page 20 If the medal was genuinally just for Erich or only Erich was named can no longer be ascertained, see also note 13 Images of the rooms can be found at https://daten.digitale-sammlungen.de/0008/bsb00087519/images/index.html?id=00087519&groesser=&fip=193.174.98.30&no=&seite=241 and https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/kunstgewerbeblatt1903/0058 (accessed 24.12.2020)

27Not only limits of time and space preclude a fuller discussion on and reflections of Gertrud Kleinhempel's furniture at this juncture, but the current realities and the associated inaccessibility of important sources mean that even if time and space allowed, we wouldn't be able to. However 2021, all going well, offers a few opportune moments for that discussion and those reflections. Also on the furniture design of Margarete Junge. And so we will definitely return to the subject.

28Amtlicher Katalog der Ausstellung des Deutschen Reichs / Weltausstellung in St. Louis 1904 page 459

29Offizieller Katalog, Dritte Deutsche Kunst-Gewerbe-Ausstellung, Dresden, 1906. The toys etc for Deutschen Hausrat Theophil Müller and C. Bühner are listed as being by "Geschwister Kleinhempel", "the Kleinhempel siblings". Fritz, Erich and Getrud were at that time all active in and with such, and so one can safely assume that works by Gertrud were presented.

30see Gerhard Renda [Ed.] Gertrud Kleinhempel 1875 - 1948. Künstlerin zwischen Jugendstil und Moderne, Verlag für Regionalgeschichte, Bielefeld, 1998 page 16-17

31Claudia Gottfried, Gertrud Kleinhempel (1875 - 1948) Professorin und Designerin, in Ann Brünink and Helga Grubitzsch [Eds.] "Was für eine Frau!" Portraits aus Ostwestfalen-Lippe, Westfalen-Verlag, 1993 page 182

32ibid page 184

33see ibid 184-185 and erhard Renda [Ed.] Gertrud Kleinhempel 1875 - 1948. Künstlerin zwischen Jugendstil und Moderne, Verlag für Regionalgeschichte, Bielefeld, 1998 page 20 - 21

34Ferdinand Avenarius, "Ein Gewaltstreich gegen das deutsche Wirtschaftsleben", Deutscher Wille: des Kunstwart, Nr 10, 2. Februarheft 1916 pages 121-125

35ibid Ferdinand Avenarius wasn't a neutral observer but very much part of the movement the article promotes. Its inclusion here has however less to do with the validity of the position presented, but to illustrate the company in which Gertrud Kleinhempel moved and her position in developments of the early 20th century.

36Gerhard Renda [Ed.] Gertrud Kleinhempel 1875 - 1948. Künstlerin zwischen Jugendstil und Moderne, Verlag für Regionalgeschichte, Bielefeld, 1998 page 99 Photo 77. The illustrated office however isn't shown at the reference quoted, and as of now we've been unable to locate the correct reference. The quoted reference does however include numerous examples of Kleinhempel's Bielefeld era furniture. Works that are, lets says, eclectic. Some resemblant of her Dresden era work, others much less so, see Moderne Bauformen Vol XII, Januar - Juni 1913 page 360ff available via https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/moderne_bauformen1913/0512 (accessed 24.12.2020)

37Gerhard Renda [Ed.] Gertrud Kleinhempel 1875 - 1948. Künstlerin zwischen Jugendstil und Moderne, Verlag für Regionalgeschichte, Bielefeld, 1998 page 22

38see Martin Lang, Arbeiten von Rich. Wörnle und Gertr. Kleinhempel, Bielefeld, Moderne Bauformen Vol XIX 1920 page 31ff Gerhard Renda [Ed.] Gertrud Kleinhempel 1875 - 1948. Künstlerin zwischen Jugendstil und Moderne lists the furniture as being 1915. Arguably on account of the War it took until 1920 to complete the furnishing of the villa

39see Claudia Gottfried, Gertrud Kleinhempel (1875 - 1948) Professorin und Designerin, in Ann Brünink and Helga Grubitzsch [Eds.] "Was für eine Frau!" Portraits aus Ostwestfalen-Lippe, Westfalen-Verlag, 1993 page 183

40ibid. Margarete Junge found herself in the same position in Dresden, see Marion Welsch, Der Gleichklang unserer Seelen tut uns wohl, in Margarete Junge. Künstlerin und Lehrerin im Aufbruch in die Moderene, Marion Welsch and Jürgen Vietig (Eds.), Sandstein Verlag, Dresden, 2016 page 110

41Künstlerin und Erzieherin. Frau Professor Kleinhempel tritt in den Ruhestand, Westfällischen Neuesten Nachrichten, Bielefelder Stadtanzeiger, Mittwoch 13. April 1938, available via https://zeitpunkt.nrw/ulbms/periodical/zoom/4697101 (accessed 24.12.2020)

42Also important to note that the majority of the men who made the running in furniture design at the start of the 20th century were trained as artists. Although many worked as architects there were only very, very few actual trained architects amongst them. And so there can be little argument that architects became furniture designers at the turn of the centuries, rather it was artists who became furniture designers. And over time predominately, exclusively?, male artists, although initially female artists were active and successful as furniture designers. Which raises the question, why? Why did furniture design become a predominately male domain?

43Erich Kleinhempel has, arguably, vanished from (hi)story for reasons very, very similar to Gertrud, and their joint disappearance being nice reminder that while gender considerations invariably play a role in how reliably, or otherwise, (hi)story records designers, it isn't the only consideration. Fate is always sticking its oar in.