In 1935 George Nelson opined that "the history of art in Italy presents the astonishing spectacle of a series of men who knew no boundaries between the arts"; a history, a tradition, Nelson saw continued into 1930s Italy through "the cheering example of Gio Ponti, who found early in life that no one profession was sufficient to use up his energy or exhaust his interests, and added others with the nonchalance of a small boy increasing his collection of marbles".1

A borderless, inexhaustible collection of marbles explored and discussed in the new Gio Ponti monograph from TASCHEN Verlag......

Born in Milan on November 18th 1891 Giovanni "Gio" Ponti, was raised in a comfortable middle class environment, and although a keen and talented academic student, young Gio's real passion was art, a passion which stood in conflict with his parents' wishes that he pursue a professional, managerial, career, a conflict which increased as teenage Gio approached the end of his secondary education; and a conflict resolved in 1911 when Gio Ponti enrolled to study Civil Architecture at the Regio Istituto Tecnico Superiore di Milano, the contemporary Politecnico di Milano. And a decision for architecture as a professional compromise in context of an artistic passion which reminds very much of Ponti's contemporary Arne Jacobsen who similarly studied architecture rather than art in order to appease his parents, and for whom, as with Gio Ponti, art was to remain a lifelong companion, a private passion and a professional mentor and inspiration, and thus very much at the heart of their respective oeuvres.

And much as the young Arne was influenced by Germanophone currents of his youth, so the young Gio; albeit whereas Jacobsen was attracted to the Functionalist Modernism of inter-War Germany, Ponti's fascination was located in turn of the century Austria: specifically the Vienna of the Secession and the Werkstätte, the Vienna of Josef Hoffmann, Max Reinhardt, Gustav Klimt, Adolf Loos, and a Vienna of which he later noted, "I owe to those examples of modern perfection of expression my first feeling of a European homeland".2

A close association with early 20th century Vienna which reminds of that other Ponti contemporary, Le Corbusier, who, as previously discussed, spent five months in the winter 1907/1908 in Vienna, thus very much in the Vienna that so affected Ponti, and where Le Corbusier famously found absolutely nothing to excite and interest him. Apart from opera. And thereby making early 20th century Vienna the first of numerous moments where, as Gio Ponti3 helps elucidate, the oeuvres of Le Corbusier and Gio Ponti approach one another while maintaining a discrete, if clearly mutually admiring, distance.

Much as the architecture of Gio Ponti is often realised as a composition of complimenting volumes, so Gio Ponti, the central two of which are a fulsomely illustrated and commented catalogue raisonné and a biographical disquisition by designer and author Stefano Casciani; two complimenting volumes which integrate with the lightness of any Ponti work to take the reader on a chronological journey through the 50+ years of Gio Ponti's career: a journey starting with his tenure as Artistic Director of the Florentine porcelain manufacturer Richard-Ginori, moving on over Ponti's, lets say, complex relationship with Italian Fascism, and on to the post-War rebuilding and restructuring of Italy, a rebuilding and restructuring in which Ponti played key practical, directorial and symbolic roles until his death in 1979, aged 87.

A journey undertaken in the vicissitudes of the many, and for all highly varied and disparate, movements, schools and currents through which Ponti's career passed; from the waning of Stile Liberty, over Novecento, Futurismo, Razionalismo, Neoliberty, and on to Pop Art and Italian Radicalism. And although Ponti concerned himself with all, he never full subscribed to any, throughout his career remaining faithful to himself, absorbing and adopting that which he considered meaningful, be that from within Italy or outwith, but always employing it in context of his own, Pontian, understandings.

A journey undertaken in the company of the many, and for all highly varied and disparate, creatives of all genres who accompanied and informed Ponti's career, including Alberto Rosselli, who was married to Ponti's daughter Giovanna, who was Ponti's business partner in Studio Ponti Fornaroli Rosselli; and an architect, designer, partner and son-in-law who, as Stefano Casciani helps one appreciate, was both an important collaborator for Ponti, but also an antipode in terms of character and approach to and understandings of architecture and design. That while the two shared common ideals and cooperated closely, they regularly diverged, not least in questions of systematisation and modularity - Rosselli pro, Ponti contra - and thus allowing Alberto Rosselli to act in Gio Ponti as a mirror for differentiated reflections on Gio Ponti.

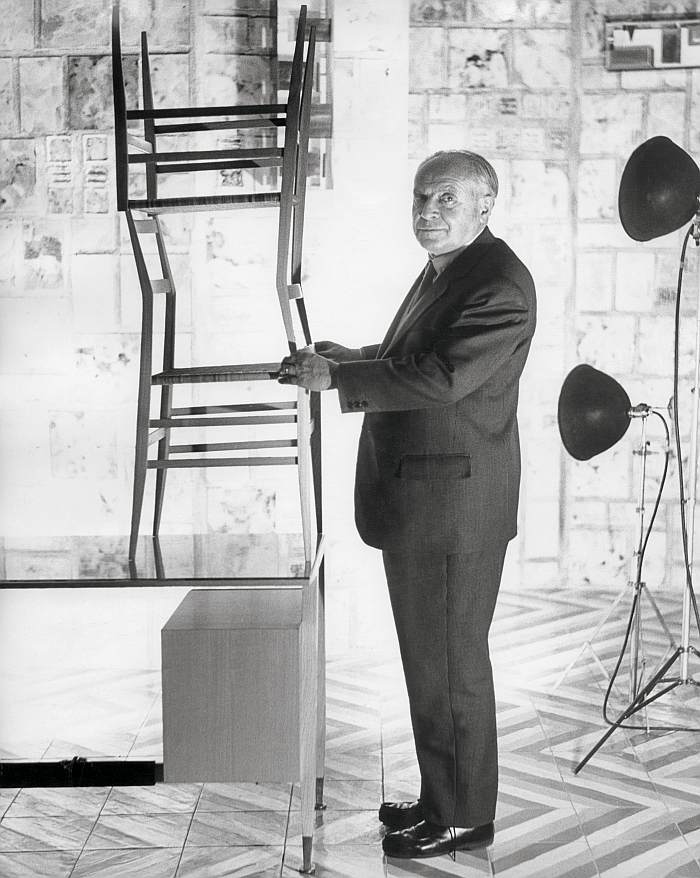

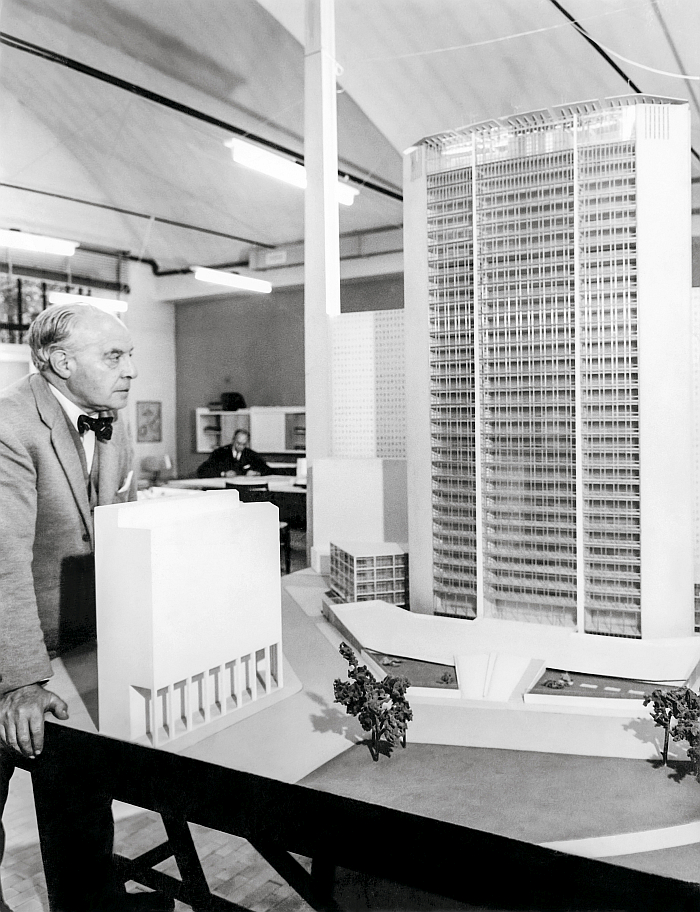

And a journey undertaken in context of the many, and for all highly varied and disparate, projects of various genres which form the sum of Ponti's career, including, and amongst many others, the magazine Domus, one of the most influential, authoritative, architecture and design magazines in Italy, which Ponti co-founded in 1928 and, save for a brief period in the early 1940s, edited, guided, defined, for the next fifty years, and an association which, as discussed in Gio Ponti, also teaches much of his appreciation of the role and importance of mass medial communication in and to architecture and design; his numerous ocean liner interiors which are as much about Gio Ponti the coordinator and impresario as Gio Ponti the interior designer, the interior artist; the Superleggera chair, that furniture design project for which Ponti is, arguably, most popularly known and which, not least through its gentle re-imaging, updating, of a centuries old Italian standard, embodies so much of Gio Ponti's design understandings; or the Pirelli Tower in Milan, that architecture project for which Ponti is, arguably, most popularly known, and a work which, according to Casciani, most faithfully encapsulates Ponti's position that "architecture is a crystal", that leitmotif of Ponti's architecture, that understanding of "the complexity, transparency, and playfulness that come together in architecture. The obvious and the secret." And which thus allows the Pirelli Tower to stand in Milan as an embodiment of Gio Ponti.

But not the only embodiment. Much as Arne Jacobsen isn't just the SAS Royal hotel, much as Le Corbusier isn't just l'Unité d’Habitation, so understanding Gio Ponti involves understanding more than just the Pirelli Tower; Gio Ponti helping that understanding develop and mature through discussions on and around architectural projects such as the Montecatini office buildings in Milan, the Faculty of Mathematics at Sapienza University, Rome, the Gran Madre di Dio Concattedrale, Taranto, or, and as one of the key works in Gio Ponti's oeuvre, Villa Planchart in Caracas, Venezuela.

Commissioned in 1953 by Anala and Armando Planchart and completed in 1957, Villa Planchart translates Ponti's vision of "a large butterfly alighted on the hilltop" on which it stands via the conceit of a shallow V-shaped roof, resemblant of butterfly wings in motion and which appears to be serenely floating above the main body. And which does float above the main body; a design concept which, in conjunction with the disjoined, independent, exterior walls helps bequeath Villa Planchart a visual lightness, reduces its visual footprint and thus helps it merge with its surroundings. And a design concept which has an uncanny similarity with Le Corbusier's Notre-Dame-du-Haut, Ronchamp: not only in the floating roof, but the way the roof curls upwards at the corners. Le Corbusier began planning Notre-Dame-du-Haut in 1950, with construction beginning in 1953, the same year Ponti began planning Villa Planchart. Which doesn't mean that Ponti took inspiration from Le Corbusier, Le Corbusier may have taken inspiration from discussions with Ponti, each may have arrived at the solution independent of the other: what it does mean is that both, either independently or through correspondence, were, simultaneously, convinced by the formal, functional and artistic arguments made by such a solution. And that despite their many differences. Differences underscored in the much more reserved realisation Ponti developed with Villa Planchart in contrast to Le Corbusier's more expressive Notre-Dame-du-Haut.4

Or at least reserved on the outside.

For as Ponti notes, as a work Villa Planchart is "not to be viewed from outside but to experience from within, penetrating it and moving through it"5, and when one does, one moves though an expressive, vivid, interior unimaginable from the quiet, reserved, exterior, an interior Ponti describes as a "game of spaces, surfaces and volumes offered in different ways to those who visit"6. And an interior to which Gio Ponti, true to his Gesamtkünsler tendencies, contributed much of the fixtures, fittings and furnishings, the latter including a coffee table realised by Giordano Chiesa, a carpenter with whom Ponti had cooperated on innumerable projects since the 1930s, and whom, as Stefano Casciani opines, was "the most sensitive interpreter of Ponti’s material dreams, eagerly following the maestro in his most difficult flights of fancy and producing objects that were working prototypes".

Such as the Villa Planchart coffee table. A coffee table featuring the tapering legs so typical, so defining, of Gio Ponti's furniture, and which we learn in Gio Ponti was a stylistic trait learned from Adolf Loos, "the foot and leg of a chair and of a piece of furniture, he used to tell me, must always be a little "too slender"", and thus an element of Ponti's work related to "those examples of modern perfection" he had understood in early 20th century Vienna; a square coffee table which features a glass plate set atop a thin metal grid, a solution which is as open and weightless as the Villa Planchart facade; a square metal coffee table whose grid is variously, and interwovenly, coloured, meaning the table appears, functions, differently depending on the perspective from which it is viewed, and which thus quotes the ever-changing perspectives Ponti realised throughout the "spaces, surfaces and volumes" of Villa Planchart, and also underscores Ponti's position that "in design as well as architecture, the viewpoint is essential and meaningful, a central starting point for every project"; a 1950s square metal coffee table which references a 1930s round burr-walnut coffee table and where not only the change in material but the more rational, less ostentatious, if every bit as reduced, formal expression underscores the evolution of Ponti's design in the intervening decades; a 1950s square metal coffee table which Ponti later employed in numerous projects as a round metal coffee table under the name Arlecchino - Harlequin - and thus evocative of the coloured geometric flashes of the grid. And a 1950s square Arlecchino working prototype available, for the first time as a square Arlecchino coffee table, in context of, and exclusively with, Gio Ponti.

Or put another way, Gio Ponti is a coffee table book that comes with its own coffee table.

And thus perhaps the start of a new genre.

It would certainly be in keeping with Gio Ponti if it was.

In a 1956 article for Architectural Record Gio Ponti explained his philosophy of architecture, noting in context of contemporary architecture that it is "obvious that the "past" and its formal tradition are no longer useful conceptually in designing this new architecture. In the context of all these new things, there is a genuine gap between the architecture of the past and our architecture. But - and here is the core of the issue - when the new architecture must be judged as a reality and a work of art, then the term "new" no longer exists, for we must evaluate it within a framework of universal and unchanging terms"7; that while the new in architecture unquestionably exists, it is, by necessity, always expressed in context of an unbroken continuum.

A position on architecture and design as moments in an ongoing continuum which reminds very much of Vittorio Gregotti's essay in the catalogue to the 1972 MoMA New York exhibition Italy: The New Domestic Landscape in which he opines that Ponti "represents both figuratively and in a sociological sense the ideal bridge with the prewar middle-class culture that found its expression in the art of 1900"8, which further reminds of Nelson's linking of Ponti with the traditions of the long history of art in Italy; an understanding of Gio Ponti as a link between the past, present and future, an understanding of Gio Ponti as a conduit via which tradition is proactively moved into the future rather than remaining a passive feature of the past, an understanding of Gio Ponti as an architect and designer who not only re-invented and re-imaged the existing, but who understood the necessity and importance of doing that, an understanding of Gio Ponti as evolution not revolution, very much enhanced by Gio Ponti.

With its focus firmly, resolutely so, on the professional Ponti biography, the personal Ponti biography being approached more through reading between the lines than reading the actual lines themselves, Stefano Casciani's text moves along at a most satisfying pace, dwelling when necessary, taking diversions when necessary, but rolling continually onwards through the works, the influences, the understandings, the relevance of Gio Ponti in a readily comprehensible and pleasingly jargon free manner; if at times the language does wander, for us, a little too far into the realms of hagiography, succumbs to the occasional outburst of hyperbole, delights as the fan rather than reflecting as the critic, which isn't a complaint, but an observation. We're not anti-enthusiasm.

And even if we were, as Gio Ponti neatly elucidates the oeuvre of Gio Ponti is of the type that is largely impervious to either critic or fandom; the fulsomely illustrated and commented catalogue raisonné allowing one to appreciate Ponti's architecture and design as possessing that unyielding composure that arises from an honesty of motivation, materials and methodology which allows it to transcend critic or fandom as effortlessly as it transcends movements, schools and currents. And also invites, admonishes, you to undertake further research on the innumerable new gems you will discover therein. And you will discover new gems.

But for all the harmonious integration of the catalogue raisonné and Stefano Casciani's disquisition allows for the development of a better, more grounded and sustainable, understanding of an architect and designer who through the borderlessness of his oeuvre, who through the inexhaustibility of his enthusiasm, who through the implicitness with which he re-imagined the existent without questioning its right to exist as it was, who through the evolution he allowed his understandings and approaches to follow, who through his understanding of the role of mass media in communicating architecture and design, who through the nonchalance with which he continually not only enhanced but diversified and updated his collection of marbles, is and was a key moment in the shaping of 20th century architecture and design.

And who, as Gio Ponti implies, can can continue to inform 21st century architecture and design, can continue to be that ideal bridge from the furthest depths of the history of art to the contemporary age. For as Gio Ponti elucidates, Gio Ponti remains a "cheering example".

Gio Ponti is published by TASCHEN Verlag, Cologne, as a multilingual - English, French, German, Italian - XL monograph.

1George Nelson, Gio Ponti, Pencil Points, May 1935, reprinted in George Nelson, Building a New Europe. Portraits of Modern Architects, Yale University Press, 2007

2and all other quotes unless stated, Salvatore Licitra et al, Gio Ponti, TASCHEN Verlag, Cologne, 2021

3We always prefer a biographic book, or exhibition, to have a sub-title that we can refer to rather than continually naming the protagonist, not least in order to aid reading. That such isn't the case here, Gio Ponti (book) is in italics, Gio Ponti (man) isn't. In addition when referring to Gio Ponti (man) we will try as often as possible to refer to only "Ponti".

4It's worth noting that in Domus 375 Ponti refers to Villa Planchart as "a "machine" or, if you will, an abstract sculpture", which is a fascinating, and not irrelevant, turn of phrase...

5Gio Ponti, A "Florentine" villa, Domus 375, February 1961

6ibid

7Gio Ponti, Out of a philosophy of architecture, Architectural Record, December 1956

8Vittorio Gregotti, Italian Design 1945-1971 in Emilio Ambasz [Ed] Italy: the new domestic landscape. Achievements and problems of Italian design, Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1972