In September 1951 the East German newspaper Neue Zeit informed its readers that, "whomever travels to Fürstenberg sees the beginnings of the new city, a city planned according to the "Principles of Urban Development".1

Whomever travels to Fürstenberg today arrives in Eisenhüttenstadt, the planned city that arose from those "beginnings"; and a city which, arguably, more than any other, stands proxy for the rise and fall of East Germany.

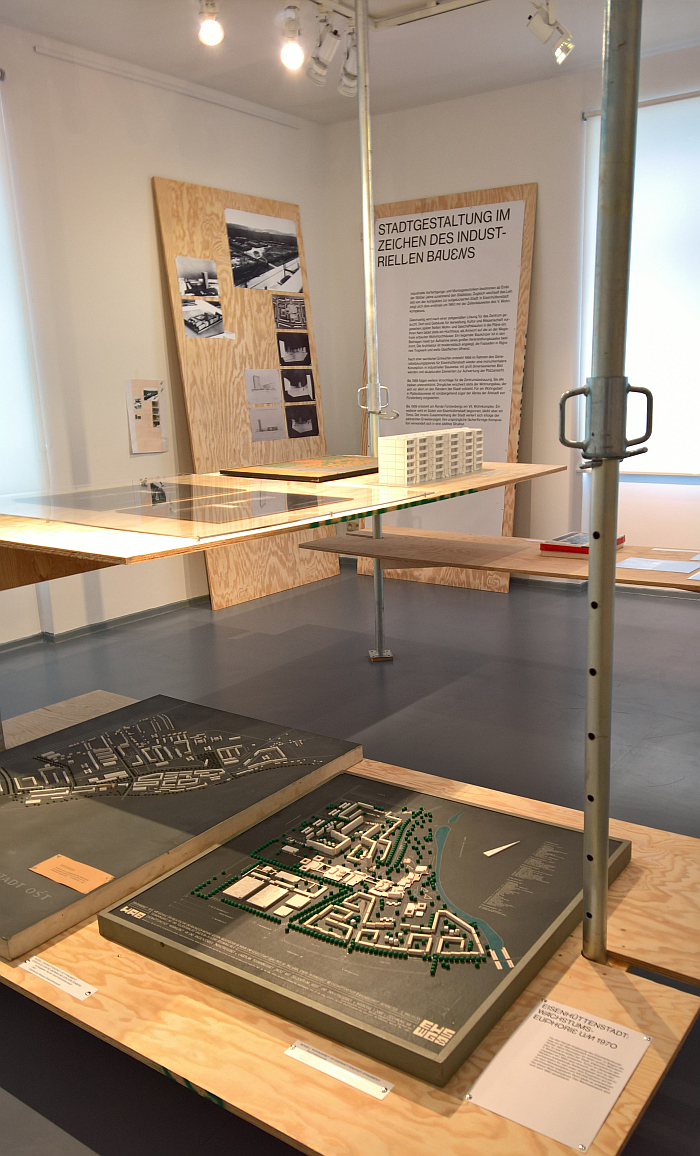

With the exhibition Endless Beginning. The Transformation of the Socialist City, the Museum Utopie und Alltag explore not only the past, present and future of Eisenhüttenstadt, but also employs Eisenhüttenstadt as a conduit for more general reflections on urban planning and the ongoing, inevitable, intrinsic, transformation(s) of our cities. Socialist or otherwise......

Tracing its (hi)story back to the 13th century, the village of Fürstenberg spent the longer part of its (hi)story untroubled by wider society, contenting itself sitting quietly and unobtrusively on the banks of the River Oder, minding its own business and watching time pass it by, much as the Oder did. Until that is, the construction of the Oder-Spree Canal in the latter half of the 19th century saw Fürstenberg become the ""shunting yard" of the eastern waterway network", the "East Gate of the waterway network between Oder, Elbe and Rhein"2, and thereby become an important hub in the increasing industrialisation of both the local region and the wider Deutsches Reich in the late 19th/early 20th century. With all the disruption to its otherwise quiet existence such a level of late 19th/early 20th century transport infrastructure invariably brought with it.

If a disruption that was but a foretaste of what was to come.

In October 1949 East Germany was formally established and in July 1950 the newly installed government published the draft of their inaugural Five Year Plan, a Plan which included the stipulation, diktat, to increase the metallurgical production of the fledgling nation by some 253%, an economic and political objective which required, amongst other initiatives, the construction of the "Eisenhütten-Kombinat Ost"3: a new steelworks with the capacity to produce some 550,000 tons of raw steel and 150,000 tons of sheet steel per annum; a new steelworks which would be "not only the most modern plant in the DDR, but in all of Europe", at least according to the, then, East German Industry Minister Fritz Selbmann4; a new steelworks to be sited, ideally, in a sparsely populated area near an established transport network, ideally near an established "shunting yard", ideally near the East German/Polish border, and which would thus allow not only the finished steel to be transported into East Germany, but also allow the required coke to be imported from Poland with minimum fuss. And a new steelworks which "will employ 12,000 workers. With family members an influx of 30,000 people is expected, for whom spacious housing developments with cultural and sports facilities are planned in the beautiful forest and lake rich area."5.

An area which was notably much less forest rich once the steelworks was operational; and "spacious housing developments with cultural and sports facilities" whose development and (hi)story form the core of Endless Beginning.

Taking the visitor on a largely chronological tour through the architectural and urban planning (hi)story of what was initially known as Wohnstsadt Fürstenberg(Oder), subsequently Stalinstadt and ultimately in 1961, and following the formal amalgamation with, devouring of, Fürstenberg, Eisenhüttenstadt a.k.a. Hütte6, Endless Beginning follows the trials and tribulations of Hütte as it rose with its steelworks, fell with East Germany and subsequently sought/seeks to reinvent itself in the realities of post-unification, post-industrial, eastern Germany.

A tour undertaken in the company of models, photographs, plans, postcards et al supported and extended by concise, informative, if German only, texts.

A tour which helps elucidate the level of planning inherent in Hütte during its East German existence, including helping elucidate how Hütte was built up sector by sector; that whereas, for example, the numbers of the arrondissements of Paris or Bezirke of Vienna have no particular relevance7, the Wohnkomplexe - Housing Complexes - around which Hütte was conceived and realised, are numbered chronologically, numbered in the order they were added, in the order they were planned, in the order they were needed.

A tour through the population dynamics of Hütte, how a city conceived for some 30,000 became home to over 50,000, before the end of East Germany initiated an ongoing slide in numbers, which means that today it is home to some 24,000, and thus approximately the number it is was planned to house. If not housing them as it had planned, the post-unification developments not following the pre-unification schema.

A tour through the numerous East German era ruins scattered throughout Hütte; ruins not for lack of ideas or lack of willing on the part of the citizens and authorities of Hütte, but on account of what Martin Maleschka tactfully refers to as the "lack of engagement of a private entrepreneur"8, and ruins which, particularly in context of the former Hotel Lunik in downtown Hütte, help focus attention on the fundamental differences between urban planning in a socialist state and urban planning in a capitalist state.

A tour which very pleasingly takes regular diversions to the planned, socialist, cities in Schwedt and Nowa Huta, diversions which help expand the narrative, introducing as they go new elements to the discourse and thereby not only allowing the Socialist City of the exhibition title to be considered more widely but for all allowing Eisenhüttenstadt to be approached in differentiated contexts.

A tour which is as much through the (hi)story of urban planing and architecture in East Germany as it is through the (hi)story of Hütte, taking you as it does from the early 1950s Formalism Debate with its demands for neoclassic, national romantic, formal expressions, and on to and over the myriad technical, ideological and aesthetic developments of state sponsored urban planning and architecture in East Germany. Including aspects such as Kunst am Bau and industrial construction which were and are very prevalent and relevant in Hütte. And which are both worthy of a trip to Hütte in their own right.

A tour which takes you to...... no, we'll come that later.

A tour which helps makes clear that for all that Hütte is and was an artificial creation, a city born and raised in the forests above Fürstenberg out of political policy and economic necessity, rather than arising of its own free will from the ebb and flow of society and populations, Hütte was and is very much a living, breathing, natural, metropolis. A city that its residents associate with, are occasionally proud to be associated with. Is a city with idiosyncrasies. Is a city that is and was much, much, more than just the sum of its Wohnkomplexe, its cultural facilities, its sports facilities, its planing, etc...

And a tour that insightful and entertaining as it is, is but the prelude to a much more informative and entertaining tour.......

A universal problem of architecture/urban planning exhibitions is the challenge of mediating something that, by definition, exists at a very large scale, on a museum scale. And for all achieving that without alienating the visitor through endless models, plans, draughts and reams of academese, reams of the impenetrable technical jargon of which architects are so very, very proud.

The simplest, and best, answer is to make the subject of the exhibition the main exhibit. Not every exhibition can. Endless Beginning can: the scale models of the exhibition existing as they do in 1:1 on the other side of the museum's windows.

And so having viewed the exhibition, having received a introduction to Hütte, what could be more natural, or rewarding, than to continue your tour on the other side of those windows, to continue your tour through the streets of Hütte, through the (hi)story of Hütte, through the Wohnkomplexe of Hütte. And for all through the aforementioned "Principles of Urban Development".

Here is, sadly, neither the time nor place for a fulsome discussion on East Germany's 16 Principles of Urban Development9, that day will however come; for now we will limit ourselves to noting that they were first published in July 1950, became incorporated into East German law in September 1950 via the so-called Aufbaugesetz10, and, arguably, are nowhere so elegantly and comprehensibly illustrated than in Hütte. Not least through the preponderance of greenery.

Which, no, isn't the first thing, or indeed colour, that springs to mind when the subject at hand is a city planned in a socialist state to house workers employed at a pre-pollution awareness era steelworks. But it is very much there. And, as one quickly appreciates, is a central component of Hütte: physically and ideologically.

"Turning the city into a garden is an impossibility" proclaims Principle 12, which, yes, does sound like a mocking critique on the Garden City movement; however, it continues, "it goes without saying, sufficient greening must be provided", which, yes, does sound like a continuation of the principles of inter-War Modernist town planning, who were greatly informed by the Garden City movement. To this end the housing blocks in Hütte are built around sprawling, at times outrageously so, inner-courtyards with varying degrees and organisation of grass, plants, trees, nature, and which not only mean every resident has direct access to a managed green space, but also means every apartment has at least one window onto greenery. And also means that you can largely navigate your way round Hütte through the courtyards, without having to concern oneself all too much with cars and roads. A separation of people and cars for the benefit of both, demanded in Principle 8. And Principle 10.

And also sprawling, at times outrageously so, inner-courtyards in which it is impossible not to imagine how many apartments you could build in them. In Berlin, London, New York, or anywhere else, they would be full of apartment blocks, collectively blocking the light and air from each other.

However, not only does the logic and charm of the green spaces engender in you a strong desire to preserve them, nor only do you begin to understand them as Hütte, but, and as you've learned in Endless Beginning, contemporary Hütte doesn't need the extra apartments. But what does contemporary Hütte need?

A question which bring us back into the Museum Alltag und Utopia, and the part of the Endless Beginning tour we skipped over earlier.

For all that Endless Beginning is about the architectural and urban planning (hi)story of Hütte, it is also very much about the future of Hütte. Is not only about the original beginning, but the contemporary and (possible) future beginnings.

Contemporary and (possible) future beginnings presented, discussed and explored in Endless Beginning's latter chapters, via reflections on themes such as, and amongst others, the manner in which Hütte is actively, managedly, shrinking towards its centre, the consequences of the new edge of town retail park, or the construction of detached family houses on the sites where once the Plattenbau high-rises towered; discussions which, if one will, bring the narrative full circle, bring the narrative back to the 1950s question(s) of how one develops an urban conurbation. Because we do develop urban conurbations.

Or as Principle 3 informs us all, "Cities 'in themselves' do not arise and do not exist".

Rather, and for all that we all like to romantically dream our urban spaces develop organically, are intrinsically of and in themselves, our cities are all planned. At least physically. Just rarely as thoroughly and consequently, and from scratch, as Hütte in the days of East Germany. Or with such urgency and acuteness in the years immediately following East Germany.

Which is what makes Hütte such an interesting and informative subject.

In its strictly planned and controlled East German manifestations Hütte can be read, understood, challenged, as if it were a theoretical model, but which was a real city with all the real data, real experiences, real lives, such produces.

While in its post-unification manifestations Hütte allows for critical reflections on the urban reinvention in eastern Germany necessitated by the demise of the East Germany on which the likes of Hütte depended for their existence; and by extrapolation on the response to the upheavals all cities, socialist or otherwise, must pass through. How does one best deal with the loss of industry, residents, status.....

And just as importantly, arguably more so, Hütte allows for critical reflections on our dealings with the legacies of East German architecture and urban planning: in its clear and concise representation of the 16 Principles of Urban Development Hütte demands, as in many regards the exhibition Anything Goes? at the Berlinische Galerie also did, a more differentiated and open approach to the varied legacies of East German architecture and urban planning. As noted, opined, from German Design 1949 - 1989 at the Vitra Design Museum, post-unification all that was eastern German tended to be considered vanquished by the western German, that while that which was once East sank in the toxic swamp of Ostalgie, that which was once West became valid and definitive. That is slowly changing. Reconsideration is demanded. And while the 16 Principles of Urban Development, and Hütte, have without question their weaknesses and much to criticise, they also have much to offer going forward. Or put another way, could, possibly, the positions, understandings, relationships inherent in their formulation, and the scars from their experiences, help contribute to the "beginnings of the new city", to the beginnings of new principles of urban development?

Answering that question involves first of all approaching East German urban planning and architecture in a distanced, objective and adult manner. Endless Beginning is an open invitation to do just that.

Making intelligent use of the challenging, if authentic 1950s, space in the Museum Utopie und Alltag's Eisenhüttenstadt home, Endless Beginning explores Hütte - and Schwedt and Nowa Huta - very much from an urban planning perspective, the Transformation of the title being the physical ones; which doesn't mean that the social, cultural, economic, political et al realities of Hütte then, now and coming, are ignored, they're not, but are very much left to the visitor to add to the discussion, or study themselves at a later date. And while all would welcome greater reflections on the social, cultural, economic, political et al transformations of Hütte, not only would such blow the confines of the challenging, if authentic 1950s, space in the Museum Utopie und Alltag's Eisenhüttenstadt home, but the primacy of the past, present and future transformations of the physical fabric of the city does allow Endless Beginning to remain firmly focussed on the important question(s) of how one develops an urban conurbation which run through its narrative. Yes, develop physically, but as we all know, while one can never completely isolate the various inputs, they all play individually in the orchestra of human co-existence.

If we did have one real complaint it would be the monolingual German presentation. As ever, we accept such a complaint can be considered unfair; however, and as so oft, our counter argument is the universality of the subject matter, that Endless Beginning is very much an exhibition for Germanophones and non-Germanonphones. And an exhibition for Hüttees and non-Hüttees.

An exhibition which allows for an engaging introduction to both the architectural (hi)story of East Germany and to the processes, problems and products of the post-unification transformation of eastern Germany; and that without the stereotyping, patronising and romanticising one so often encounters.

An exhibition, for all in conjunction with a long post-exhibition walk, which allows not only for an engaging introduction to Hütte, but for all allows one to better approach the relevance, the importance and the wherefores of Hütte, of Hütte as it was conceived to be and what it became, both theoretically and practically.

And an exhibition which in being such, allows for reflections on that most pertinent question posed by the exhibition Die Stadt. Between Skyline and Latrine at the smac – Staatliches Museum für Archäologie Chemnitz: Wem gehört die Stadt? To whom does the city belong?

Reflections one automatically undertakes as one tours the planned Wohnkomplexe, the East German era ruins, the post-unification additions, the post-unification removals, or the, for us, very poetically undeveloped Zentraler Platz; reflections which in their very specific Eisenhüttenstadt context allow for differentiated reflections on them in their wider, universal, context: reflections on the tension between the city as a simultaneously individual and collective entity, on the city as an inextricable component of the society in which it exists, on the city as a space which normalises behaviour while inciting to rebellion, on the city as transient and permanent, on the city as finite, on the city as infinite, on the city as an ongoing work in progress. On the city as an endless beginning.

Endless Beginning. The Transformation of the Socialist City is scheduled to run at the Museum Utopie und Alltag, Erich-Weinert-Allee 3, 15890 Eisenhüttenstadt until Sunday May 29th

Full details can be found at www.utopieundalltag.de

And as ever in these times, if you are planning visiting any exhibition please familiarise yourself in advance with the current ticketing, entry, safety, hygiene, cloakroom, etc rules and systems. And during your visit please stay safe, stay responsible, and above all, stay curious……

1Nicht nur Wohnblöcke, auch ganze Städte, Neue Zeit, Nr 207, September 7th 1951, Page 3

2Ein neues Wirtschaftszentrum blüht auf, Neue Zeit, Nr. 208 September 7th 1950, page 4

3Das Gesetz über den Fünfjahrplan, Berliner Zeitung, Nr. 255 November 2nd 1951 (possibl page 3, unnumbered in our copy)

4Eisenhüttenkombinat bei Fürtsenberg, Berliner Zeiting, Nr. 192 August 19th 1950, page 1

5ibid

6Eisenhüttenstadt translates literally as Ironworks City, which yes does sound as if it should be in mid-West USA...... Hütte is foundry/smelter/mill/etc.

7Yes some do, but the vast majority don't

8Martin Maleschka, Architekturführer Eisenhüttenstadt, DOM publishers, Berlin, 2021.....We assume it is Martin Maleschka, the author isn't named. Apologies of it isn't.....

9https://www.bpb.de/geschichte/deutsche-geschichte/wiederaufbau-der-staedte/64346/die-16-grundsaetze-des-staedtebaus (accessed 17.09.2021

10Formal title is the ever glorious, "Gesetz über den Aufbau der Städte in der Deutschen Demokratischen Republik und der Hauptstadt Deutschlands, Berlin (Aufbaugesetz)" and in which stands "§ 7 Für die Planung und den Aufbau der Städte sind die vom Ministerrat der Deutschen Demokratischen Republik am 27. Juli 1950 beschlossenen „Grundsätze des Städtebaues“ zugrunde zu legen."