In the final decades of the 19th century the lands of the, then, German Empire, established themselves amongst the leading protagonists in the developments of contemporary applied arts as they moved towards that which we today term design. A leading position which, in certain regards, became a European dominance in the course of the 1900s, 1910s and 1920s through the contributions made to the evolving practices, processes, expressions and understandings of the period by institutions such as, and amongst many others, the Deutsche Werkstätten Hellerau, the Deutsche Werkbund, the Frankfurt city building authorities and, and perhaps most famously, the Bauhauses.

Then, as so oft in 1920s Europe, came the 1930s, the War and subsequently the establishment within (part of) the lands of the, former, German Empire two new nations: West Germany and East Germany.

And what became of the design understandings and approaches that had developed and evolved in that region over the previous half century?

That, to misquote Hamlet, is one of the questions the Vitra Design Museum pursue in German Design 1949–1989. Two Countries, One History.

It was, in retrospect, perhaps indicative of how the coming (hi)story of Europe would develop that the Second World War ended twice on the European continent: on May 7th 1945 in Reims, France, where Germany surrendered in the American military headquarters, and on May 9th 1945 in Berlin-Karlshorst where Germany surrendered in the Soviet military headquarters. The double surrender, and as with so much of the coming decades, being a thoroughly unnecessary act, and much more an embodiment of prevailing geopolitical tensions amongst the "Allies". For all tensions between America and the Soviet Union; tensions which led in May 1949 to the founding of the Federal Republic of Germany, BRD, West Germany, and in October 1949 to the founding of the German Democratic Republic, DDR, East Germany.

And which is where German Design 1949–1989. Two Countries, One History begins ... conceptually. As an exhibition German Design 1949–1989. Two Countries, One History opens post-1990 with a prologue that is also an epilogue, and a chapter to which we'll return......

.......and start with a journey through German Design's main narrative as its unfolds in the course of three chronologically flowing chapters; starting in 1949-1960, and thus years of not just a new start after the Nazi dictatorship and the War, but of two new starts in two new contexts as the two new nations sought to establish both a national identity and to define their relationships not only with a new neighbour with whom they shared a long, and in recent times unpleasant, (hi)story, but also within the post-War political landscapes and economic markets.

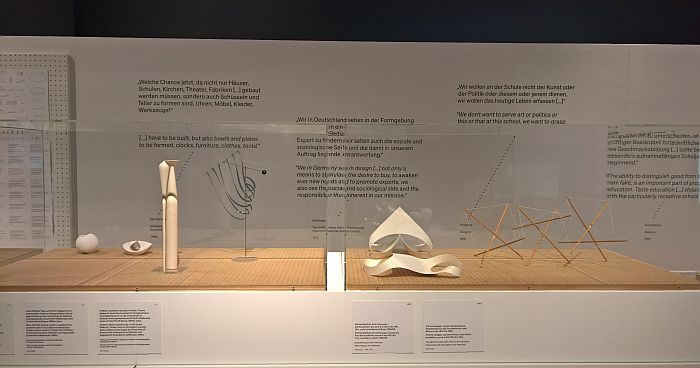

A process with which German Design's first chapter opens, including making brief mention of the Formalism Debate in early 1950s East Germany, a "debate" which, and simplifying more than is prudent, saw the East German authorities denounce the principles and practices which had underscored inter-War Functionalist Modernism, denounce the most recent design understandings and positions of the region, and demand more ornament heavy and national romantic orientated formal expressions in architecture and design, and a "debate" which although brief echoes throughout the (hi)story of post-War East German architecture and design. A silent echo in context of the great many architects and designers the fledgling East Germany lost on account the Formalism Debate including, and amongst many others, Herbert Hirche, Marianne Brandt, Wilhelm Wagenfeld, and Mart Stam, the latter who, as previously discussed, had travelled from Holland to help with the development of East Germany, before being denounced along with his positions and understandings of and to design.

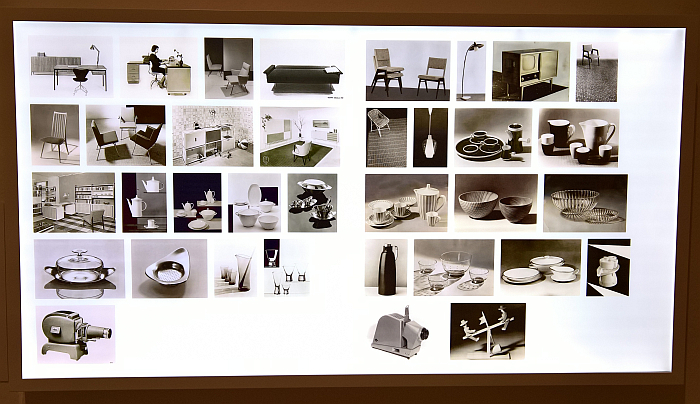

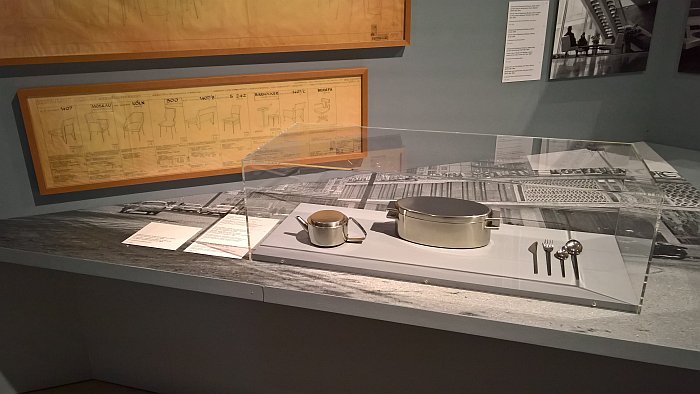

Having briefly delineated the political and economic contexts of the immediate post-War years in the new two Germanys... .....two Germanies? .....two Germanys? .....two Germanys, German Design moves sprightly on to an exploration of the development of design in the two Germanys in the 1950s, for all the design of household objects of all genres, an exploration undertaken in context of subjects such as design education, the development of formal expressions or design mediation, the latter helping elucidate how through exhibitions, publications and institutions such as the Deutsche Werkbund in West Germany and the Institute für Angewandte Kunst in East Germany acceptance was sought, encouraged, forced, at (semi-)official levels for the formal expressions being developed by industry and design schools. A (semi-)official sought/encouraged/forced acceptance of a gute Form which, in both the west and the east, was widely, although not exclusively, understood as a continuation of the reduced, rationalised, ornament free forms of inter-War Functionalist Modernism.

Or at least was in East Germany once the ebbing of the Formalism Debate allowed such forms to be officially tolerated.

The ending of German Design's opening chapter in 1960 is no random event, much more is related to the commencement in August 1961 of the construction of the Berlin Wall; an object which not only came to define both the two Germanys and post-War Europe, but an act which underscored the rising geopolitical tensions of the period, of the intensification of the Cold War; tensions which provide the background to the chapter 1961–1972.

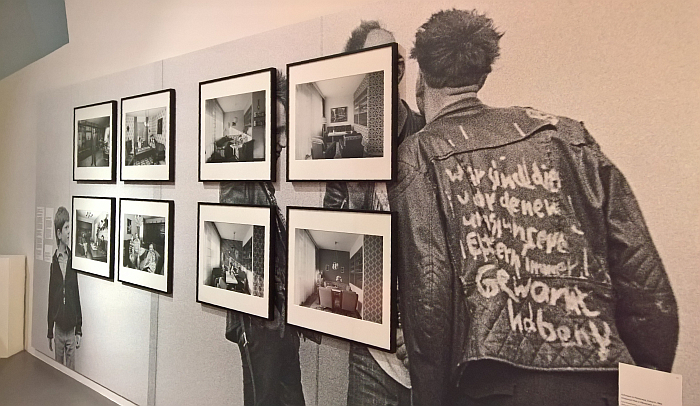

A chapter presented in a space which most pleasingly is itself divided in to East and West by a wall, an implied wall, an implied wall physically signified by photos; and a space in which the Vitra Design Museum have genuinely written OST in black letters on a yellow background. Which will mean nothing to the greater many of you, but which is going to delight a lot of people in Dresden when the exhibition opens in the city's Kunstgewerbemuseum in October, representing as it does a cry of belief amongst a section of the Dresden populace of their primacy in contemporary eastern Germany, and which, we predict, will result in a flood of bengalos and balaclava photos should it be repeated for the presentation in the city's Kunsthalle im Lipsiusbau.... but we digress....

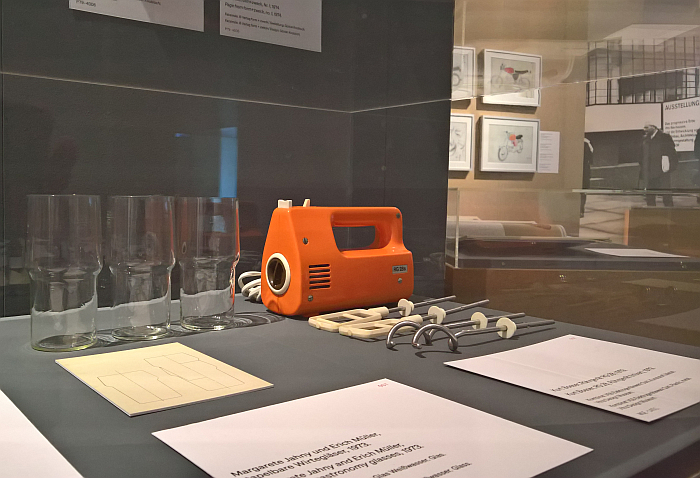

A divided space that discusses divided subjects such as, and amongst others, the rise of mass, serial, production in East Germany for everything from crockery to housing, or the development of graphic and corporate design in West Germany, including examples of the corporate identity developed by Otl Aicher and his team for the 1972 Munich Olympics, that event which has such a complicated place in West German (hi)story. And a divided space which also features the unified concept of System Design; an understanding which had its origins, as with so much presented thus far in German Design, in the inter-War decades, and which became firmly established as a design concept in the 1960s. And which is exemplified in German Design, is used in German Design as conduit for discussion, via Dieter Rams' 1960 606 shelving system from Germany (West), and by Rudolf Horn's 1966/67 Montagemöbel Deutschen Werkstätten, MDW, from Germany (East).

The latter famously being described, derided, at its launch by the, then, de-facto East German Prime Minister Walter Ulbricht, as "das sind ja nur Bretter”, that’s just planks. Which it was. And is. And which is and was the whole point. And helps underscore that while the Formalism Debate may have ebbed, remnants of it remained in the higher echelons of East Germany's ruling elite Genossen.

German Design formally reaches its conclusion with the years 1973–1989, a period which opens with the political and social aftermath of 1968 and also the political and economic shock of the oil crisis, before moving over a global economic downturn, the rise of neoliberalism in the lands of the "West", the growth of popular, mass, dissatisfaction in the lands of the "East"; evolving political, social, economic, et al landscapes, which, and as previously discussed from 1989 – Culture and Politics at the National Museum Stockholm, culminated in that most notable of years with its many notable moments, including the practical if not yet formal, end, after four decades, of the two Germanys. And a period discussed in German Design via subjects such as, and amongst others, an increasing understanding of the necessity for more sustainability in design approaches, or perhaps more accurately, the beginnings of an increasing move towards the beginnings of understandings of the necessity for more sustainability in design approaches; by the rise of computers, something reflected on in the west via a 1989 Apple Macintosh SE by Esslinger Design, an early forerunner of the contemporary apple identity, and in the east by the Robotron 1715 from the ever gloriously monickered VEB Robotron Büromaschinenwerk "Ernst Thälmann" in Sömmerda, and a work which can also be seen on a photo from the 1987 parade to celebrate Berlin's 750th anniversary being pulled through East Berlin on trolleys. Proof, were it needed, that it was East Germans who invented mobile computing....... sorry.......

.........and a period also discussed via an increasing rejection by designers of the prevailing industrial and economic systems, an increasing refusal to cooperate with, to conform within, the prevailing industrial and economic systems. A rejection and refusal which, as oft noted in these dispatches, formulated itself in West Germany in what became known as Neues deutsches Design, a barely definable disparate collective of approaches and positions, if which through a unified questioning of the values of design, the relevance of the design profession, the relevance of industrial production, of design's relationship to society, stands as a definitive moment in the (hi)story of design in West Germany; and a moment represented in German Design by, and amongst other works, Consumer's Rest by Stiletto Studios with its implicit rejection of not just consumerism but of a lazy, formalistic, representation of Bauhaus. Which, yes, does sound a bit like Luigi Colani.

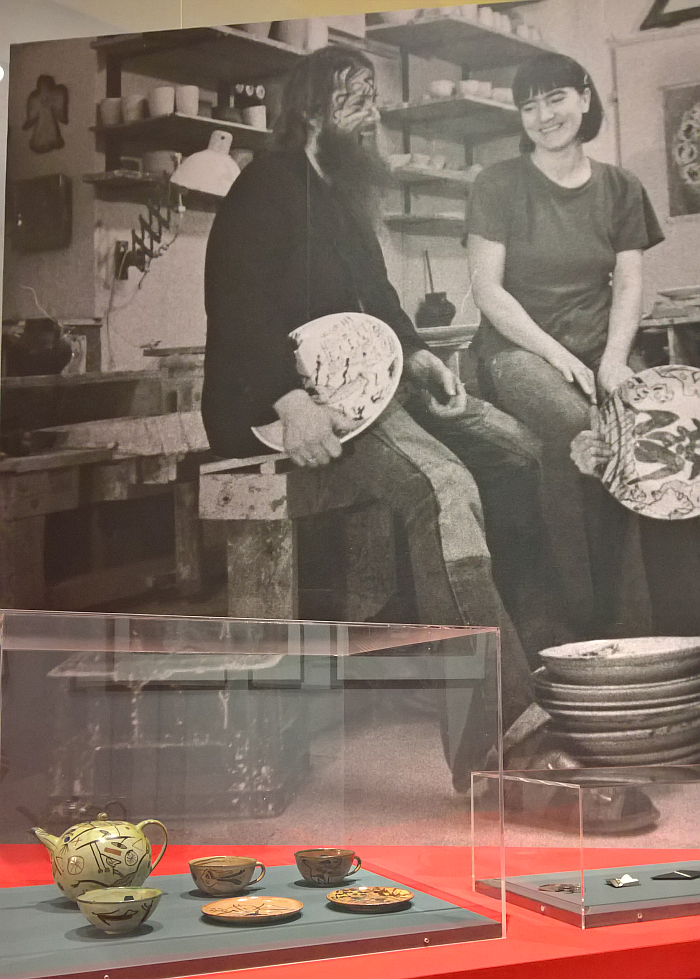

And a rejection and refusal of prevailing realities by designers in East Germany which, as German Design argues, was based primarily in an opposition to the mass production of cheap export goods which the ebbing of the Formalism Debate had allowed, and on which the East German authorities relied for income, but which had only little interest in design. And even less interest in designers. And a rejection of contemporary industrial production in 1980s East Germany which is embodied in German Design by a tea service by Wilfriede Maaß and Karla Woisnitza realised in Maaß's ceramics workshop in Berlin-Prenzlauer Berg and decorated with, what we're calling, idiosyncratic patterns; and which for all is symbolic of a move in 1980s East Germany from industrial production to craft production as a future orientated design strategy. Which, yes, does sound a bit like William Morris. And also, if one so will, stands as a reversion of Walter Gropius's "Art and technology, a new unity" to his original "Art and craft, a new unity". And that just after the East German leadership had (finally) formally acknowledged Bauhaus and its contribution to the development of design understandings. Thereby allowing East German designers to formally question both those contributions and the prevailing Bauhaus reception; and that alongside, in unity with, their colleagues in West Germany. If still in two independent nations.

A late 1980s reality which, as we all now know, would soon change. Would become, as Gropius would no doubt have phrased it, "East and West, a new unity"

The final scene in German Design is the scene that led to end of the two Germanys, the fall of the Berlin Wall; an ending which, for us, tends towards recollections of those many, many, songs where the band are obviously unsure how to end, and so just fade out with a repetitive instrumental. Or just stop. And hope no-one notices. But everyone always does. And asks themselves ????

Not that the ending detracts from what has come before it, it doesn't; it just feels a bit forced, a bit disjointed, is highly puzzling, curious, as a moment in the presentation. And for all poses the question if there wouldn't have been a better way to lead out of the (hi)story of four decades of design in the two Germanys.......

......and which brings us back to the prologue that is also an epilogue.

Or more accurately, brings us to the path which leads to the prologue that is also an epilogue.

As an exhibition German Design can, ideally should, be approached and viewed from a number of perspectives.

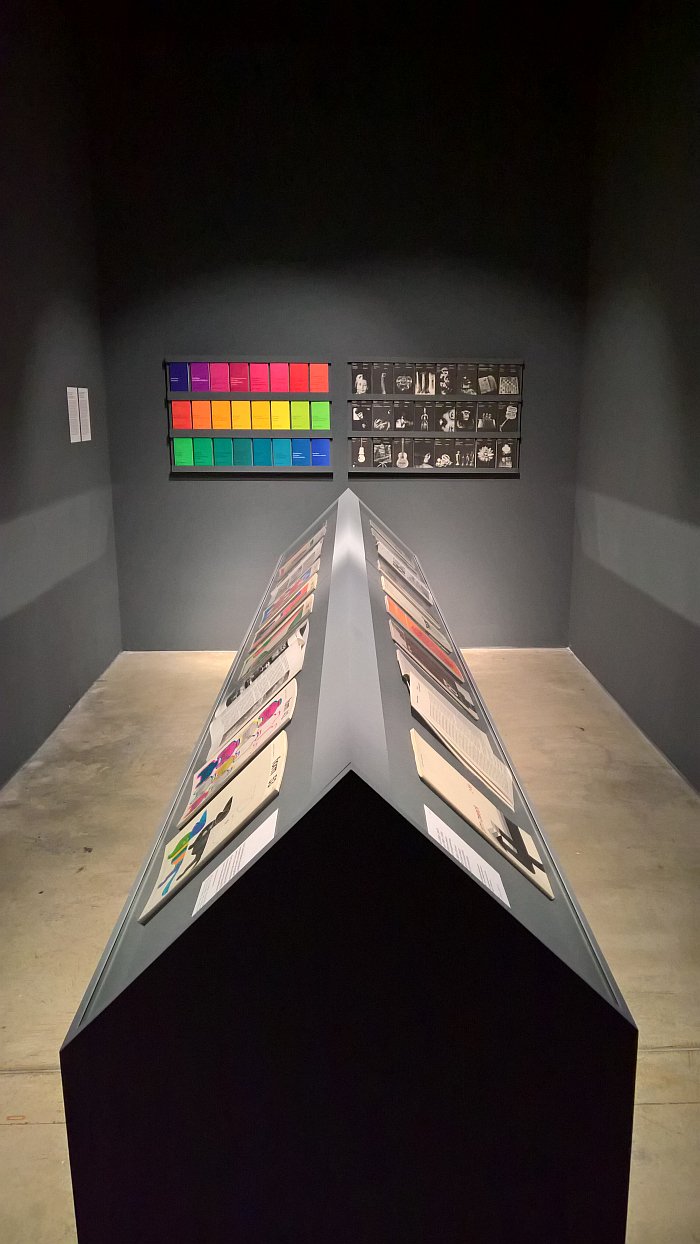

On one level it is a straight comparison of the developments in East Germany and West Germany, an opportunity to reflect on similarities and differences, and that not just in terms of a comparison of specific objects/genres, but also, for example, comparisons of the design education in the two Germanys, comparisons of the responses to questions of resource scarcity, comparisons of materials and production process, comparisons on the mediation of design, or comparisons on the nature of the design discourse in the two Germanys: the latter being neatly, and very pleasingly, enabled by a presentation of editions of the principle West German design magazine form and the principle East German design magazine form+zweck [form + function/purpose] which allows one to read - in German, obviously - how design was described, reported and presented in the two Germanys.

Then there is the comparison of the continuation within the two Germanys of the understandings, approaches and expressions they had inherited from pre-War generations; or perhaps better put, a comparison of how the understandings inherited from pre-War generations evolved and developed post-War in the two Germanys.

A comparison which leads into a second approach to viewing German Design: the developments in West Germany and East Germany as components of wider, international, developments in design and design understandings. Simplifying dangerously, the move depicted in German Design from a relatively strict adherence to inter-War understandings in the 1950s and 60s over an increased environmental focus in the 1970s and on to protest and Postmodernism in the 1980s, wasn't a progression that only occurred in the BRD and DDR, but was international, if always in a national context and always with a distinct regional dialect. But how does the manifestation of that progression differ in the two Germanys, individually and collectively, from that elsewhere, how does the relationship to the inter-War understandings and approaches change in the two Germanys over the four decades, individually and collectively? And why?

Reflections which lead into a third approach to viewing German Design, for us, in many regards, the most important approach, that of design as not being about objects but about objects, about our tools of daily life, as expressions of responses to prevailing realities; and an approach to viewing German Design which takes you away from the two Germanys and into wider considerations on design. Or perhaps more accurately, is an approach to viewing German Design which allows the development of design in the two Germanys to be used as a conduit to considerations on design in wider contexts; as a conduit to an understanding of design not as something one can post on Instagram but as a component of ongoing social, cultural, economic, technical, political et al processes, and that both as an individual response and position on the part of the respective designer, but also a response that can be, often is, guided and influenced, both directly and indirectly, by the state. That culture and politics are inalienably and inextricably linked.

While on a more basic level German Design can, and without question will, be approached by all former East and West Germans, from a fourth perspective: the "Oh! we had one of them!", "Oh! remember that!", "Granny! Look! It's your coffee pot!", which is inherent in any design exhibition featuring mass market design that is still in living memory, any exhibition which features cultural artefacts that are both found in museum collections and still in daily use. And of which there are a great many in German Design. And which looking forward could be one of the more interesting components of the exhibition, one of the more interesting comparisons: the comparison of its reception in Weil am Rhein in deepest, darkest West Germany with its subsequent reception in Dresden in deepest, darkest East Germany; the comparison of its reception in the former West and its reception in the former East. A comparison which in many regards the Trabant P 601 in front of the Vitra Design Museum stands as a harbinger: an exotic rarity on the streets of Weil am Rhein, an object which is almost a synonym for East Germany amongst many West Germans, an object which in many regards is symbolic of the distance that existed between East and West; and which is part of the daily cityscape in Dresden, an object which is almost a synonym for East Germany amongst many East Germans, an object which in many regards is symbolic of the complexities of Ostalgie, that nostalgia for all things Ost. And which poses the question, will the Trabant P 601 stand in front of the Kunsthalle im Lipsiusbau in Dresden, or will there be a Opel Manta in its place......?

And considerations on the reception of the exhibition amongst individuals of varying backgrounds which will make any future presentation of German Design outwith Germany's contemporary borders particularly interesting; a presentation before a public for whom the many objects on show have no cultural or practical relevance, a situation akin to viewing an exhibition of design from the 19th century or earlier, and thus a presentation where the viewers must work their way into the exhibition's subjects and themes without any experience or understandings won through the works on show. Or perhaps better put, must work their way into the exhibition's subjects and themes with their existing understandings of design in West Germany and of design in East Germany.

And which, finally, brings us to the prologue that is also an epilogue.

The years immediately following German unification were, we don't feel it's overly exaggerated to claim, years of ongoing, ceaseless, Ossie/Wessie conflicts as the four decades of two Germanys, four decades of the indoctrinated understandings of the other Germany, of the prejudices and jingoism which had been drip-fed to both populaces over the decades and thus four decades of mistrust - as we oft note fake news ain't new, alone the means of its dissemination are - hindered a smooth social and cultural fusion.

Those conflicts have, thankfully, (largely) faded in recent years and thereby allowed for more sober and differentiated reflections on the four decades of two Germanys, reflections without the finger-pointing and insults that once accompanied, defined, such. Indeed one could argue that only now with the benefit of a generation and bit hindsight are more sober and differentiated reflections possible.

Reflections the Vitra Design Museum undertake, contribute to, from a perspective that post-unification East German design is all to often presented as, discussed as, and thus understood as, both in the lands of the former West Germany but also, and on account of the former West Germany's position in international structures, globally, as something secondary to the more dominant West; that West German design and West German lifestyles are accepted as valid, authentic, meaningful, while the design and lifestyles of East Germany are considered spurious, insignificant, at best cheap copies of western models, and all enforced by and subservient to political doctrine. The Trabant, for example, is a joke, the VW Golf an ideal.

The time, so one could paraphrase German Design, has come for a little more objectivity.

Consequently, and in our reading of German Design, the Vitra Design Museum understand German Design not only as a review of design in West Germany and of design in East Germany in the years 1949 to 1989, but also as a platform to rectify the prevailing popular view of and understandings of design in the former East Germany, a vehicle by which to move towards that which we referred to from the exhibition Shaping everyday life! Bauhaus modernism in the GDR, as an "understanding of design in the DDR which transcends the lazy, the superficial, the cliched", and to do such via not only more sober and differentiated considerations on the development of design in East Germany, but through undertaking those considerations parallel to more sober and differentiated considerations on the development of design in West Germany, and thereby allowing more sober and differentiated, more objective, reflections on not only the similarities/differences of and between design in the two Germanys, but also the similarities/differences of and between the contexts within which design developed. And thereby allowing a move towards more probable understandings of design in West Germany and of design in East Germany.

And which also allows an alternative perspective on the decision to park a Trabant P 601 in front of the Vitra Design Museum: makes it a statement of intent. And thus that it may indeed be as appropriate in Dresden as in Weil am Rhein.....time will tell......

An intent, and understanding of itself and its function, that German Design flags up in its prologue, and which in doing so allows one to enter the exhibition's narrative with a heightened awareness that those opinions you had on the relative merits of design from the former East and the former West upon arriving on the Vitra Campus may have been were skewed, may have been were informed by decades of poorly substantiated generalising and unreflective repetition, and thereby enabling you to enter the exhibition more openly, more open mindedly, than arguably would otherwise have been the case. And while German Design, for our tastes, flags up the problems of the prevailing understandings of design in East Germany a little to uncritically, in its keenness to acknowledge a bias in the West German/global reception of East German design, in its keenness to see that amends are made, that the field is levelled, it becomes, for us, a little too eager to please East Germans, forgets/ignores that East Germans are very much part of the equation, which we suspect will become all to evident in Dresden, and certainly German Design's definition of Ostalgie which makes it sound like Hygge and not the root of many, many evils it is, has caused us untold sleepless night since visiting the exhibition, and which is a subject we will, must, must, must, return to... but, again, we digress.... and while German Design, for our tastes, flags up the problems of the prevailing understandings of design in East Germany a little to uncritically, it is an action we very much approve of; understandings of the (hi)story of design in East Germany, as with understandings of the (hi)story of design in West Germany, are very much in need of a reload and that starts with reassessing the path we've taken to our contemporary understandings.

And which for all makes the prologue a good place to both start and finish your tour through German Design, makes it a prologue that is also an epilogue: start in the space as a prologue, tour through the four decades and return to the space as an epilogue in the company of the impressions and reflections acquired during your tour, and compare the impression(s) the arguments and positions presented in the space made on you as a prologue and make on you as an epilogue. Is there a difference?

In addition the prologue poses a question which is the wrong question, but when reformulated as the correct question, we'd argue, can't be answered until it is posed in an epilogue.......

A well paced, coherent and engaging exhibition which discusses it themes and subjects via a wide variety of design genres supported by concise bilingual German/English texts aided and abetted by condensed timelines of the decades under consideration, one of the more pleasing aspects of German Design is the variety of themes and subjects it introduces and thereby the breadth of the discussion it allows, nay demands. If a breadth coupled to the unavoidable limitations of time and space which mean that German Design can but skim briskly over post-War design in the two Germanys, something tacitly confirmed by the brevity of its discussions on, for example, the Formalism Debate or on Neues deutsches Design, and also the treatment of many of its subjects and themes as but snapshots of a specific period rather than ongoing discussions throughout the four decades, as an exhibition is has no opportunity to dive to any great depth; however, all exhibitions have to decide if they go in breath or depth and in context of German Design breadth is correct, being as it is a decision which allows German Design to help you achieve a more advantageous position from which to establish an overview of the wider landscape of 20th century design in Germany. While all the time confirming you are receiving but an overview; its brisk narrative presenting as it flows a myriad moments which imply that there is a lot more to learn, while the manner in which it does so motivates, nay demands, you continue your own studies later, and as Oscar Wilde teaches us, the answers are all out there, just rarely in popular design books, one must read a little deeper and keep your eyes open for smaller, more, specialised exhibitions. German Design is, can only be, but the start of a journey. And is an entertaining and engaging place to start.

As pleasing as the breadth of the exhibition is the way German Design doesn't let its narrative get distracted by designers and/or manufacturers; that while a great many of the names you would expect to find in any discussion on design in West Germany and East Germany are present, in addition to a great many who may/will be new, who are rediscovering their place on design's helix, they are all present as examples not as themselves, and in doing so allows the narrative to remain resolutely focussed on the development of design in the two Germanys and for all on the frameworks, contexts, constraints and discourses within which design developed in the two Germanys. And which in doing so helps reinforce that design in the two Germanys, as with design anywhere, isn't the objects but what they embody. That your focus shouldn't be the object in front of you, but what that object represents, its place in the narrative, its relevance to and for the narrative.

A state of affairs which allows German Design to help one approach not only better, more durable, more resilient, understandings of the development of design in East Germany and of the development of design in West Germany, but also to use those developments as a means to approaching better, more durable, more resilient, understandings of the development of East Germany and West Germany: exactly because design is a response to prevailing realities it is also an excellent medium via which to understand the societies in which it arose; the cultural artefacts of 1950s West Germany or 1960s East Germany are no different from the cultural artefacts of the Roman Empire or Xia dynasty. Are just cultural artefacts that you might still use on a daily basis. And thus much as the exhibition is German design in the years 1949–1989 it is also very much the two Germanys in the years 1949–1989; is as much an exhibition about approaching better understandings of the (hi)stories of the contemporary Germany as it is about approaching better understandings of the design (hi)stories of the contemporary Germany.

Which brings us to the aforementioned question posed in the prologue that, we'd argue, is the wrong question, but when reformulated as the correct question can't be answered until it is posed in an epilogue........: Two countries, One History?1 A question whose answer is "yes", it's the unquestion-marked sub-title of the exhibition; however, the more pertinent question, the question that should be asked is, Two Histories, One Country? Which yes, we do mean in a social, cultural context. Where is Germany in 2021?

But also where is design in Germany in 2021? No nation is ever definable by a unified, single, design understanding, even the design in the Germany of the 1930s and early 1940s had variations in its expressions, but where is design in Germany in 2021?

And which we'd argue is how one should leave German Design, or rather when one should leave German Design: in 2021 not in November 1989. That one should leave German Design not only with reflections and considerations on the four decades of design and design developments in the two Germanys as presented and discussed in the course of the exhibition, but one should also leave German Design pondering the question where, after three decades of unification, design in the contemporary Germany finds itself both domestically in terms of not only its approaches, positions, formal expression, understandings etc, but in terms of its relevance, its standing, its value, its values, and also where it finds itself in an international comparison: what became of the leading early 20th century position in design the German Empire/Republic enjoyed? What have the experiences of the period 1949–1989 in West Germany and East Germany contributed to design in Germany in the period 1990–2020? What have the experiences of the period 1949–1989 cost design in Germany in the period 1990–2020? What have the understandings of the value of East German design in the period 1990–2020 cost design in Germany in the period 1990–2020? What have the understandings of the value of West German design in the period 1990–2020 cost design in Germany in the period 1990–2020?

Or put another way, much as German Design asks what became in the years 1949–1989 of the design understandings and approaches that had developed and evolved in that region over the previous half century before 1949, as an exhibition it also demands consideration on what have become of the design understandings and approaches that developed and evolved in the region over the near half century between 1949 and 1989 in the three decades since.....

German Design 1949–1989. Two Countries, One History is scheduled to run at the Vitra Design Museum, Charles-Eames-Str. 2, 79576 Weil am Rhein until Sunday September 5th. After which it will, as noted, move on the Kunstgewerbemuseum Dresden.

Full details can be found at www.design-museum.de/german-design-1949-1989

And as ever in these times, if you are planning visiting any exhibition please familiarise yourself in advance with the current ticketing, entry, safety, hygiene, cloakroom, etc rules and systems. And during your visit please stay safe, stay responsible, and above all, stay curious……

For all who can’t make it to Weil am Rhein, or indeed who can but who wish to experience more than the exhibition itself, the Vitra Design Museum have a digital fringe programme. Full details can be found at www.design-museum.de/german-design-1949-1989-digital

1Update 09.11.2021 - Having viewed German Design 1949–1989. Two Countries, One History in Dresden, we now understand the title - the history referred to is that between 1949-1989, not, as we assumed pre-1949..... And in terms of design one can, must, question in how far 1949-1989 is and was one history..... we'd however still argue the more pertinent question in terms of histories and countries is Two Histories, One Country?