Rudolf Horn – Wohnen als offenes System @ the Kunstgewerbemuseum Dresden

In 1968 the East German designer Rudolf Horn opined that “the changed tenor of industrial production in the socialist society, in relation to its task of satisfying cultural needs on a mass scale, raises the question of how despite mass production the consumer can realise an individual [domestic] environment, and in addition forces us to consider the problem of how the cultured personality can creatively contribute to the design of their immediate surroundings.”1

How indeed….?

It was, however, a largely rhetorical question, because, and as the exhibition Rudolf Horn – Wohnen als offenes System at the Kunstgewerbemuseum Dresden explains, in 1967 Rudolf Horn had already formulated an answer, or perhaps more accurately put, in 1967 formulated a framework via which to allow each and everyone of us to approach our own answer…..

Born in Waldheim, Sachsen, on June 24th 1929, Rudolf Horn’s career began as a teenage apprentice carpenter and aircraft constructor during the last years the War, before post-War he moved into those spheres where he’d not only make a name for himself, but living rooms for many an East German: interior architecture and furniture, specifically, interior architecture studies in Mittweida and a tenure with VEB Möbelwerke Heidenau. In 1952 Rudolf Horn took up a position within the East German Ministry for Light Industry before in 1958 being appointed Head of the Office for Development, Trade Fairs and Advertising in the Furniture Industry; parallel to his office jobs Horn studied at Dresden Engineering College and the Hochschule für industrielle Formgestaltung Halle, the contemporary Burg Giebichenstein Halle, graduating in 1965 as a Diplom-Formgestalter, [Designer] before in 1966 joining the institute’s staff as Director of the newly established Furniture and Interior Design Department, and where he remained until his retirement in 1996.

Shortly after taking up his post in Halle Rudolf Horn was approached by the Deutsche Werkstätten Hellerau to discuss the possible development of a potential project. A possible, potential that became the so-called Montagemöbel Deutsche Werkstätten, MDW, a variable furniture system, if you will a possible, potential furniture system, that went on to become not only one of the biggest selling furniture lines in the DDR, nor only a furniture system which outlived the DDR, nor only a furniture system which challenged, and contributed to changing, existing ideas on furniture and interiors, but for all a system which is very much one of the path Rudolf Horn took from apprentice aircraft constructor to Diplom-Formgestalter.

And a system which was, in many regards, to guide his future path.

All he had to do was find that path.

Montagemöbel Deutsche Werkstätten, MDW, by Rudolf Horn for Deutsche Werkstätten Hellerau, as seen at Rudolf Horn – Wohnen als offenes System, the Kunstgewerbemuseum Dresden

In 1953 the magazine Holz und Wohnraum – Wood and Living Space – published a summary by Rudolf Horn, at that time a 23 year old newbie in the Ministry for Light Industry’s Wood and Cultural Goods Department, of the exhibtion Neue Möbel unseren Werktätigen – New Furniture for Our Workers – which had travelled through East Germany not only presenting proposals for contemporary interiors, but gathering opinions from visitors on those proposals. And not only the title of the exhibition indicates it was a DDR exhibition, also Rudolf Horn’s text is very much of early 1950s East Germany, not only making plentiful reference to the central position of the worker in society, the need to ensure the workers requirements are fulfilled in their entirety, and use of the rhetoric of the national Kulturerbe, cultural heritage, but also noting that the responses to the exhibition demonstrated that East Germans rejected the “pernicious influences of formalism, which is an integral part of American cosmopolitanism”2. A rejection one imagines most East Germans were thoroughly unaware they were undertaking, and a rejection phrased, as is the whole text with its talk of the negative reception afforded the “Zierlichkeit“, delicateness, of much of the work and a tangible “demand for solid furniture”, in the highly programmatic language of the Formalism Debate of the early 1950s, that period, as previously discussed, when in an attempt to establish a sense of national identity in the fledgling German socialist republic, and for all a national identity distinct from that (those?) prevalent in West Germany, East Germany followed Stalin’s lead and declared the contemporary, for all the influence of the inter-War Modernists, the enemy of the worker, the enemy of the Werktätigen.

And thus not exactly fertile ground from which the functionalist understanding of design that so underscores not only the MDW system but Rudolf Horn’s oeuvre, could ever hope to grow.

A state of affairs which poses two very obvious questions, ??? as regards the text, and how were the seeds of functionalism sown and cultivated?

“I was still very young, I was still searching for my way” Rudolf Horn replies in answer to the first, “and all around me were these theses, the workers are the masters of the country, and must be made to feel as such. It wasn’t a position that I followed with a proud, wide, breast, but was all around at that time.”

The latter question has a number of answers, or perhaps better put the answer to the latter question has a number of components, the first being found in the April 1953 edition of Holz und Wohnraum in which Horn’s text appeared: an obituary for Josef Wissarionowitsch Stalin whose death in March 1953 ended the Formalism Debate, and thus the opening of new possibilities for young creatives, possibilities that until the arrival of Nikita Khrushchev as Soviet President and the softening of Moscow’s position to, well, pretty much everything, would have been unthinkable.

A second component, arguably, being found within the 1953 text itself. It could be we’re creating realities here that never were, are over-romanticising to the point of falsehood, have finally lost the plot, we appreciate that, as should you dear reader; however, in his text Horn lists four, what he refers to as, “conclusions of fundamental importance”, which can be summarised (interpreted with the benefit of 66 years hindsight?) as that the displayed furniture didn’t correctly respond to the needs of the Werktätigen and that more exchange between user and designer needs to occur; the attempt to enforce a cultural heritage through furniture was often overdone, was too deeply rooted in the past, and thus rejected; furniture designers need to understand the spirit of the times; and the inadequacies of the contemporary East German furniture industry to meet the challenges of the period. Yes, arguably very friendly conclusions which helped the responsible Ministers forge their future policies; but also understandings of furniture, the furniture industry and the role of the furniture designer at the interface between consumer and industry which form central pillars in Horn’s work. Or put another way, the text opens with the statements that “the working people of our republic know very well what furniture they want” and that “that they know whether a living room or a bedroom meets their needs, their demands, or not”, while in his final sentence Horn notes that the exhibition has the potential “to overcome the existing weaknesses in order to accelerate the development of a true, realistic home decor”3 It certainly appears to have had that potential in context of Rudolf Horn.

A potential aided and abetted by a third component, that which Horn refers to as the “Lebenslehre“, “life’s lessons” which he learned from those Professors under whom he studied, including a number of late period Bauhäusler such as Selman Selmanagić, Friedrich Engemann or Walter Funkat, Lebenslehre, and Professors, which as he explains he was exposed to during his time in the DDR bureaucracy, where he not only developed “an overall economic perspective, one not only learned from the point of view of industry, but from the point of view of the wider national economy” but also was exposed to the denunciations of works by his teachers as “Barracks Lockers” and “Margarine Crates”, a situation that led to what he refers to as “a long process of deliberation” with himself, the concept of a national cultural heritage, economics, the furniture industry, the ideas of his teachers and the contemporary society, and deliberations which led him to side with his teachers and their “Barracks Lockers” and “Margarine Crates”, and thus to find the way he’d been searching for in 1953. And the path to MDW.

A product which, very appropriately, added to the vocabulary of invective directed towards contemporary furniture when the DDR’s then First Secretary Walter Ulbricht dismissed the system as “nur Bretter.” Just planks. Yup. But in fairness one shouldn’t expect a DDR politician to understand the complexities and demands of the social, cultural and economic realities of the DDR.

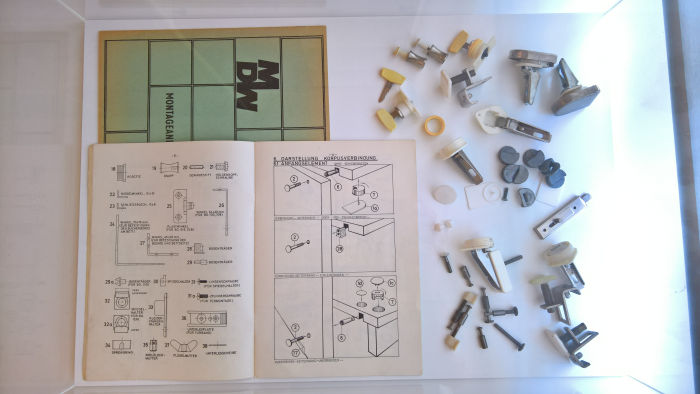

MDW components and assembly plan, as seen at Rudolf Horn – Wohnen als offenes System, the Kunstgewerbemuseum Dresden

Prior to MDW Rudolf Horn had developed several modular furniture systems, including the so-called Leipzig IV programme, the new, the innovative, decisive on MDW was that the final user decided the layout, it wasn’t simply cupboard, drawer, shelving, desk et al modules that one could place on or next to one another, but components which could be freely assembled to form cupboards, drawers, shelves, desks et al, a system that one could individually configure, which, yes, sounds patently obvious, there being today a myriad furniture systems where you configure the layout yourself, and as with MDW alter it as and when required or needed. There weren’t in 1967. In 1967 furniture, not just in East Germany but globally, was generally monosyllabic, static objects with static functions.

However in 1967 increasing security, prosperity and population meant that individuals and society were becoming increasingly active, variable, and articulate, an evolution that by necessity required furniture that was equally active, variable and articulate. And not only were consumers evolving, but industry: new production technologies, new materials and new economic realities were forcing questions to be asked about how objects are produced, the means of production were changing, not means of production in the Marxist sense, but in the practical sense. And evolving means of production which had to concur with the evolving demands of an evolving population.

And thus we arrive at the conundrum of achieving individuality in mass production. A conundrum which takes us back to the inter-War years and the conundrum of individuality in standardisation. As ever, questions rarely change, the possible answers continually do.

For Rudolf Horn the answer in the late 1960s was to make in his words, the user the finalist, industry supplies the basic elements, the user decides what to do with them. And if at a later date they want to do something else with them, they can. It’s their furniture, their home, their life. No-on elses.

And thus rather than offer a large selection of fixed objects, a concept which as Horn argues is uneconomic, doesn’t conform to the contemporary social realities and can’t lead to a genuine individual expression, the furniture industry should offer, as Horn wrote in 1981, “weniger Typen mit mehr Varianten“4, “less types with more variants.” Less is more.

Not the only connection to Mies van de Rohe, either in Rudolf Horn’s biography, or in Wohnen als offenes System ⇓ ⇓ ⇓. Or indeed the only connection to Bauhaus, MDW often being quoted as an example of a continuation of Bauhaus thinking, whereby its important to understand that Rudolf Horn is very much a designer of the Hannes Meyer Bauhaus: one, for example, can’t imagine Rudolf Horn in an Itten’s Vorkurse, paying much attention to Moholy-Nagy, and certainly there is, we feel, little point in buying Rudolf Horn tickets for Schlemmer’s Triadisches Ballett for Christmas. Rudolf Horn is much more a designer aware of design as a responsibility rather than an art, of design as a social responsibility, an economic responsibility, MDW is as much a system for industry and it is for the user, a system devised with an awareness of the realities of the contemporary industry, industry’s needs and understanding that the designer is as much a partner of industry as of the end customer; and also an environmental responsibility, the latter being an integral part of the MDW concept, an understanding that variability and adaptability lead to durability and longevity, not least as an alternative to the consumption of static, monosyllabic objects presented in ever new guises, or as Horn once railed, a furniture industry that constantly gives “essentially the same objects the appearance of being new, different and original” and all that under the mantra, “Long live the show, the historical quotation, the banality, the transitory””5, and leading inevitably to “objects bound to the modes of fashionable trends whose moral wastage and replacement is calculated” and which ultimately leads to “forms of consumption which contradict the socialist values, because they consciously destroy material and work effort”.6 And today he still rails with just as much passion against unnecessary waste, if with a little less reference to socialist values and more to contemporary logic. And hard fact.

Examples of existant MDW systems, as seen at Rudolf Horn – Wohnen als offenes System, the Kunstgewerbemuseum Dresden

In addition to the Bauhaus connection, the most regular connection made in context of the MDW system is IKEA, in East Germany it is colloquially known as DDR IKEA. Which although it in many ways is, it also isn’t, or certainly not Billy which everyone means, and thus rather than DDR IKEA, DDR Billy, which would make it Willi, or post-Wende Mitteldeutscher Willi…..sorry ….. we digress… back to the subject at hand….. Not only was Billy released in 1978 and thus a good decade after Willi MDW, but to refer to it as DDR IKEA is also to fail to understand a fundamental difference: whereas Billy was developed as a bookshelf, and has largely remained as such, MDW is/was a complete system that could be used in any room of the house and which from the very beginning encompassed all manner of components, and thus whereas altering Billy to meet your individual needs involves participating in the popular pastime of Hacking IKEA, MDW was designed to be adapted. It is in many regards open source furniture. If not open design, although there is an argument to be made for that transition.

Or put another way.

Rudolf Horn’s decisions were made on the realities of the late 1960s, and our decisions must be made on the realities of the late 2010s: Rudolf Horn had new woodworking machinery, an expanding, increasingly wealthy, self-confident and educated population, we have have multiaxis CNC machines, 3D printers, cornucopias of new materials, demographic changes specific to our increasingly global society, the internet and all manner of digital technologies. Is therefore a freely available, online, furniture system which allows anyone anywhere to create an interior to their needs, and then adapt it to their new needs when they move somewhere else, including adding to it via pieces from the same system and thus in the same dimensions, not a perfectly contemporary solution? And would it not also take the “user as finalist” model a significant step further as the user can also freely select the material? Mitteldeutscher Willi has proved his worth in eastern Germany, let him go global. Yes, it would destroy the current shelving and storage furniture industry, but would mean a lot more work for local carpenters, or those furniture stores clever enough to install some saws, mills, planes, 3D printers and hire a carpenter or two.

And is that not in addition an elegant manner by which to both respond to the fact the DDR regime failed to fully commit to Horn’s idea, never implemented MDW in its entirety, failed to grasp the inherent concept and how that concept was taking root outwith the confines of the DDR, and then inexplicably messed about with the fundamentals of the system, but for all respond to that very contemporary question, namely “how the cultured personality can creatively contribute to the design of their immediate surroundings.”

Interiors from the Variable Wohnen apartments in Rostock, as seen at Rudolf Horn – Wohnen als offenes System, the Kunstgewerbemuseum Dresden

A bijou showcase Wohnen als offenes System not only introduces and explains the MDW system, it’s background, concept and how it was used, is used, as part of the exhibition individuals have submitted photos and texts explaining how their systems are still employed, and lest we forget production ended in 1991, meaning even the newest system is over 25 years old, but also as an exhibition explores on the one hand how Rudolf Horn transposed his understanding of open systems, less is more and the user as finalist into other materials, something very elegantly demonstrated by the modular polyurethane system PUR produced by VEB Holz Naumburg; on the other hand explores how Rudolf Horn transposed his understanding of open systems into architecture, for all the Variable Wohnen project which saw the creation of 54 variable apartments in Rostock, but also saw show homes in Dresden and Leipzig, and which employ the same user as finalist theory and apply it to the complete living space, allow users to decide on the position of the walls and not just those things placed on/next to them; and on the rare, and therefore particularly satisfying, third hand, underscores how Rudolf Horn’s understanding of open systems stood directly juxtaposed to the closed system in which his work was realised, or put another way, and as we noted from the exhibition Shaping everyday life! in Eisenhüttenstadt, “objects in the DDR, unlike political or economic policies, being transparent, democratic and conceived to last.”

The various furniture and architecture systems being supported in the exhibition by examples of other DDR homeware that was used in the numerous MDW publicity photos, DDR magazine articles on Horn, and an example of Horn’s Conferstar chair for Röhl Potsdam, a work which, as previously discussed, represents Horn’s adaptation of Mies van der Rohe and Sergius Ruegenberg’s famous, and according to Horn, “beautiful, but so uncomfortable”, Barcelona Chair, and which can also be considered as an expression of Mies’s position that “…each material has its specific characteristics which we must understand if we want to use it. This is no less true of steel and concrete. We must remember that everything depends on how we use a material, not on the material itself”6

Something demonstrated in many regards not only in Horn’s reworking of the Barcelona Chair to the Conferstar Chair, but in his reworking of modules that can be placed on or next to one another into a freely configurable system.

Conferstar chair by Rudolf Horn for Röhl Potsdam, as seen at Rudolf Horn – Wohnen als offenes System, the Kunstgewerbemuseum Dresden

Initially conceived as a simple showcase of the MDW system, Wohnen als offenes System is a jauntily paced exhibition, one that takes the visitor fluidly, comprehensibly and entertainingly through not only the story of MDW but how the process that led to MDW continued throughout the 1970, 1980s, 1990s to both the numerous others staging posts on Rudolf Horn’s career and also an evolution in understandings of furnishings, the relation between consumer and producer and indeed the role of the consumer in the furniture industry. And that that role needn’t, shouldn’t, be passive.

And also an exhibition which implies there is a much, much more fulsome Rudolf Horn exhibition out there, waiting to be invited in, one that not only explores in more depth Rudolf Horn’s positions to and understandings of design, the various projects not included in Wohnen als offenes System, his time at Burg Halle and influence of his design positions of coming generations, but which also reflects in more detail on his architectural work, not just in context of his furniture design work but for all in context of the Deutsche Bauakademie and Wilfried Stahllknecht’s Plattenbau developments, but also in context of the work of a Fritz Haller or the West German Neue Heimat housing association; of the relevance of Horn’s time in East German bureaucracy in the 1950s and 1960s, positions which, much like Edward J Wormley’s war time tenure in the Office of Price Administration, gave him an insight into how industry works that most designers don’t have, and how that shaped his understanding of furniture; of MDW in context of the history of the Deutsche Werkstätten Hellerau, for all in context of programmes such as Richard Riemerschmid’s Maschinenmöbel, Bruno Paul’s Wachsende Wohnung, or Franz Ehrlich’s 602, a programme which in many regards MDW replaced. And three programmes which the intelligent exhibition design means one can experience, and reflect upon, in the Deutsche Werkstätten Schaudepot upon leaving Wohnen als offenes System.

Until that exhibition comes, Rudolf Horn – Wohnen als offenes System offers not only sufficient material to help one both better understand the man, his work and his positions, and to encourage you to do more research yourself, but for all helps one understand that it is possible to mass produce individuality, if one mass produces variability and trusts the consumer a little.

Rudolf Horn – Wohnen als offenes System runs at the Kunstgewerbemuseum, Schloss Pillnitz, August-Böckstiegel-Straße 2, 01326 Dresden until the 2019 season ends on Sunday November 3rd.

In addition the exhibitions table talks — Tischgespräche and Add to the Cake: Transforming the Roles of Female Practitioners can also be viewed until November 3rd.

Full details, including information on the accompanying fringe programme can be found at https://kunstgewerbemuseum.skd.museum

1. Rudolf Horn, Industriell gefertigte Montagemöbel, Deutsche Architektur, XVII Jahrgang, March 1968

2. Rudolf Horn, Was lehrt die Wanderausstellung “Neue Möbel unseren Werktätigen” die Architekten?, Holz und Wohnraum I Jahrgang, No.3, 1953

4. Rudolf Horn, Der Nutzer als Finalist, Form+Zweck 13. Jahrgang No.6 1981

5. Quoted by Rudolf Horn, original referenced as Heinz Hirdina, Nachwort zu Claude Schnaidt, Umweltbürger und Umweltmacher, Fundus-Bücher 83/84

6. Rudolf Horn, Serie, Vielfalt und Bedarf, Form+Zweck 18. Jahrgang No.6 1986

7. Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, inauguration address, 20.11.1938 quote in Carsten Krohn, Mies van der Rohe – The Built Work, Birkhäuser Verlag, 2014

- PUR by Rudolf Horn for VEB Holz Naumburg, as seen at Rudolf Horn – Wohnen als offenes System, the Kunstgewerbemuseum Dresden

- Coffee service “Diamant” by Astrid Löffler-Lucke for VEB Porzellanwerk Freiberg, as seen at Rudolf Horn – Wohnen als offenes System, the Kunstgewerbemuseum Dresden

- Sketches by Rudolf Horn, as seen at Rudolf Horn – Wohnen als offenes System, the Kunstgewerbemuseum Dresden

- A wardrobe from Richard Riemerschmid’s Maschinenmöbel programme for Deutsche Werkstätten Hellerau

- Kontrast lamp by Lutz Rudolph for VEB Leuchtenbau Lengenfeld, as seen at Rudolf Horn – Wohnen als offenes System, the Kunstgewerbemuseum Dresden

- The interior of an experimental show flat in Dresden, as seen at Rudolf Horn – Wohnen als offenes System, the Kunstgewerbemuseum Dresden

- MDW by Rudolf Horn and a desk from the 602 programme by Franz Ehrlich, both for Deutsche Werkstätten Hellerau, as seen at Rudolf Horn – Wohnen als offenes System, the Kunstgewerbemuseum Dresden

- MDW assembly amnuals, as seen at Rudolf Horn – Wohnen als offenes System, the Kunstgewerbemuseum Dresden

- Rudolf Horn – Wohnen als offenes System, the Kunstgewerbemuseum Dresden

Tagged with: Deutsche Werkstätten Hellerau, Dresden, Hellerau, Kunstgewerbemuseum Dresden, MDW, Montagemöbel Deutsche Werkstätten, Rudolf Horn, Schloss Pillnitz, Wohnen als offenes System