"Reinforced concrete is the best constructional material yet devised by mankind", enthused the Italian civil engineer Pier Luigi Nervi in 1956.1

A position Nervi spent a circa sixty year career arguing for, both in innumerable texts and through a canon of varied, and varyingly challenging, constructions throughout Italy, and much further afield. And in doing so Pier Luigi Nervi not only helped advance a popular acceptance of reinforced concrete as a construction material, but also helped develop an argument that in context of our built environment how we construct is, in many regards, more important than what we construct. An argument that has lost none of its contemporaneous since Pier Luigi Nervi first advanced it.......

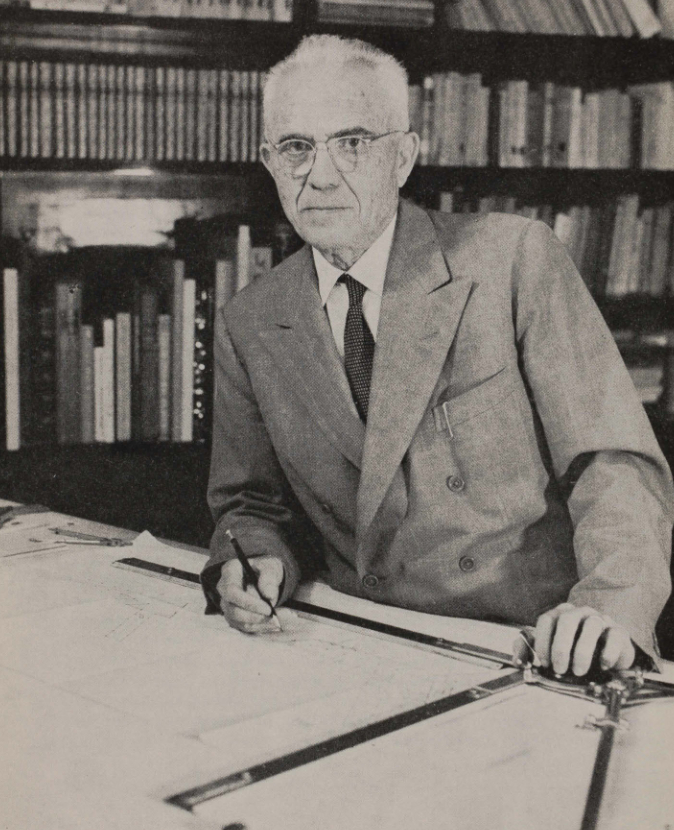

Born on June 21st 1891 in Sondrio, northern Lombardy, the young Pier Luigi Nervi was raised in Savona2, on the Ligurian coast between Genova and Nizza, before in 1909 enrolling at the Regio Scuola d'Applicazione per Ingegneri e Architetti in Bologna, where, following the compulsory two year general course in mathematical, physical and natural sciences3, he specialised in the Faulty of Engineering, and met two individuals of fundamental importance in the laying of his future path: Professor Silvio Canevazzi, the, then, director of the Scuola and an important, if primarily theoretical, proponent of reinforced concrete in late 19th/early 20th century Italy, and Professor Attilio Muggia, a former student of Canevazzi who was amongst the first practising constructors in early 20th century Italy to routinely employ reinforced concrete.4

Following his graduation in 1913 Pier Luigi Nervi took up a position with Muggia's Società Anonima per Costruzioni Cementizie, initially in the Bologna office and subsequently, and following a Great War enforced hiatus, in the company's HQ in Florence where, as one of only two civil engineers at that time5, he quickly took on responsibility for his first commercial projects, including, for example, developing the roof of the pelota pavilion for Adolofo Coppedè's redesign of Florence's teatro giardino Alhambra, and also innumerable bridge projects. Thus very much projects primarily concerned with the cold, detached, objectivity of civil engineering.

That however would soon change.

In 1923 Pier Luigi Nervi parted company with Cementizie, and with Attilio Muggia, relocating to Rome where he established Società Ing. Nervi e Nebbiosi, which while sounding like the fictional New York detective agency at the heart of a series of not very funny comedy novels, was a construction company established in cooperation with one Rodolfo Nebbiosi, as best we can ascertain, pun intended, a building contractor, and in which context Nervi developed projects such as, and amongst many others, the roof for the Teatro Politeama in Prato as Nervi e Nebbiosi's first major project; the roof for the Teatro Augusteo in Napoli, an early project which Claudio Greco notes Nervi "counted as his personal favourite"6; and a palazzina on the banks of the Tiber in Rome designed by the architect Giuseppe Capponi, an apartment block in which family Nervi lived, and that work which first brought Pier Luigi Nervi to the attention of Domus magazine7, and, and arguably more importantly, its founder and editor-in-chief Gio Ponti: even if Nervi's structural solution was hidden behind a facade of travertino. Similarly his technical solution for the free-standing spiral staircase that winds its way majestically between the ground and fourth floors, a technical solution of which Ponti makes particular, and extended, note, and a staircase, and one presumes solution, Nervi first conceived in context of his 1913 graduation project in Bologna.8

Pier Luigi Nervi's most important project in the years immediately after leaving Cementizie was, unquestionably, the Stadio Giovanni Berta in Florence, the contemporary Stadio Artemio Franchi, or simply Comunale, one of the first major projects authored by Pier Luigi Nervi rather than, as with Capponi's Roman palazzina, an architect's project to which Nervi contributed as an engineer. Or as Nervi phrases it, Comunale was "the first major work that presented me with a technical and aesthetic problem"9: the former Nervi approaching through the search for an "economically valid" structural solution, that is, "the most natural and spontaneous solution", "the method of bringing dead and live loads down to the foundations in the most direct way and with the minimum use of materials".10 The latter Nervi comprehended after "long and patient work to find an agreement between static necessities ... and the desire to obtain something which for me would have a satisfying appearance" was, essentially, given by the same "economically valid" structural solution: "the static guide gave suggestions which in themselves were esthetically expressive when translated into drawings"11 and which thus needed but little modification; that, for example, while "the variation in section of the main ribs is determined by the law governing the variation of moments", "purely aesthetic considerations inspired the slight curve of the canopy and of the haunching of the main ribs".12 Or put another way, "the most natural and spontaneous solution", combined with a well considered, judicious, minimal, formal intervention by Nervi, produced a technically and formally satisfying result. An experience, an appreciation, that was to fundamentally inform not only Nervi's approach to his work, but also his understanding of his role and function.

In addition Comunale was that project, that experience, that appreciation which, according to Claudio Greco13, led Nervi to part company with Nebbiosi and to establish in 1932 the partnership Società Ingg. Nervi e Bartoli with his cousin Giovanni Bartoli. A platform which allowed Pier Luigi Nervi the freedom to autonomously develop major projects from the planning to the construction.

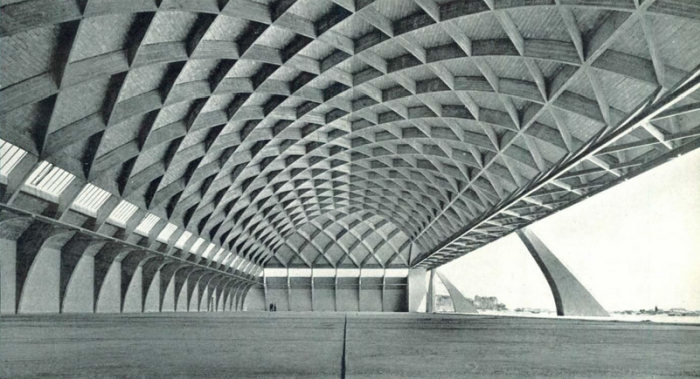

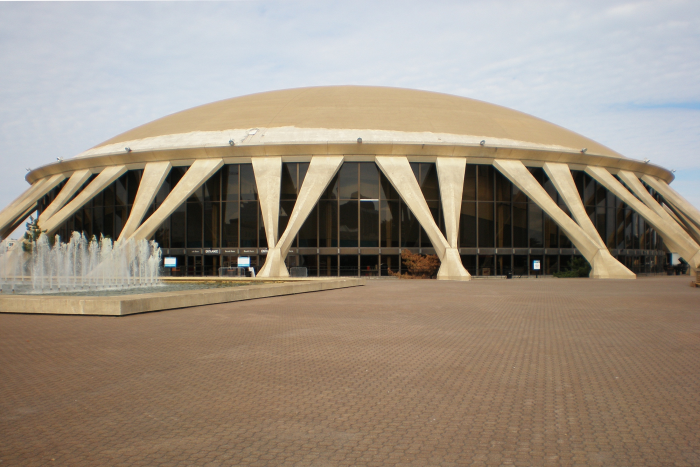

To develop projects as varied as, and amongst a great many others, two families of aircraft hangers developed in the late 1930s for the Italian army for which Nervi, as one of the very first, used scale models to undertake "a detailed study of the stresses by means of experimentation"14; the Società Burgo paper mill in Mantua with its roof suspended like a bridge; the large and small indoor sports arenas for the 1960 Olympics in Rome with their expansive vaulted domed roofs; the George Washington Bridge Bus Station in New York City for which Nervi, as one of the very first, used a computer to analyse complex static system15: or his contributions to architect led projects such as Marcel Breuer and Bernard Zehrfuss's UNESCO Campus in Paris or Gio Ponti's Pirelli Tower in Milan.16

To develop the processes and methods of constructing with reinforced concrete, something attested to by the 40+ patents he acquired17, and in particular to develop and advance novel methods of working with pre-cast reinforced concrete elements, to develop and advance novel typologies of reinforced concrete, for all Nervi's developing of ferrocement18, to develop and advance novel approaches to constructing the frameworks employed for casting reinforced concrete, for all Nervi's developing of non-wooden frameworks, thereby freeing reinforced concrete construction from the constraints of the properties of wood, constraints which only allow for constructions that could, at least formally if not statically, also be created in wood, and thereby to allow reinforced concrete to reveal, and regale in, its full potential.

To develop aesthetic positions in context of architecture and the urban environment, and that not only through the absence of decoration or ornamentation beyond that bequeathed from the construction itself, but for all through leaving his buildings standing proudly in their exposed concrete, showing their workings to all who cared to look. Allowing his buildings to be themselves. Unmasked.

To develop the argument that, in context of its structural, formal, functional, economic et al properties, possibilities and advantages "reinforced concrete is the best constructional material yet devised by mankind".

To develop into one of the more important, interesting and informative constructors of the 20th century.

Pier Luigi Nervi died in Rome on January 9th 1979 aged 87.

For all the very obvious temptation to approach Pier Luigi Nervi through the buildings he realised, and much as we'd recommend anyone unfamiliar with Pier Luigi Nervi's canon to invest time to become better acquainted with the myriad works therein, you won't be disappointed, they are in many regards of secondary importance in context of assessing and considering Pier Luigi Nervi's relevance: then, now and future.

Much more important, on the one hand, is Pier Luigi Nervi's appreciation of the fundamental importance of novel materials and novel technologies in the development of architecture, his appreciation of the lesson that throughout (hi)story it has been novel materials and novel technologies as much as evolving economic, social and/or political realities that have driven the development of architecture, and of the necessity of contemporary constructors understanding and working with the specific characteristics of novel materials (and (associated) novel technologies) to develop novel architecture. His material happened to be reinforced concrete, but regardless of what it had been he, inarguably, would have progressed in an analogous manner, for as Ada Louise Huxtable delightfully opines, Nervi possessed "a brilliant technical mind, unhampered by conventional attitudes, exploring without prejudice the potential of a still unknown material".19 Not that Pier Luigi Nervi was a proponent of revolution, his works may have been revolutionary, joyously so at times, but his approach was very much one of evolution, and reading his first Charles Eliot Norton lecture20 one can clearly see him placing reinforced concrete construction in a continuum that flows from classical antiquity over the "truly miraculous"21 progress of the Gothic builders of whom Nervi was such an ardent admirer on to the cast-iron construction of the 19th century that marks the start of rational technical/scientific construction, and ultimately to his own period. And a continuum flowing from antiquity that, we'd argue, can today be observed flowing from a Pier Luigi Nervi into the future: Nervi's works, his approach to his work, his understanding of his work helping elucidate how to 3D print a building.

Or more accurately, helping elucidate how to construct a 3D printed building.

For it is in construction that one unquestionably finds Pier Luigi Nervi, in that "oldest and most important of human activities", one which on account of "its varied aspects, of its persistence in time, and of the scientific, technological, esthetic, and social factors which influence it ... may well be considered the most typical expression of the creativity of a people and the most significant element in the development of its civilization".22 Yet construction which for centuries had and has been hidden behind facades, concealed by detail and decoration. Pier Luigi Nervi contributed greatly, fundamentally, to liberating construction, to freeing construction, and in doing so, in showing his workings and thereby highlighting the relationships between the means and methods of construction and the finished work, Nervi helped and helps us all to better appreciate the relevance of efficiency in the development of our built environment. A multifaceted efficiency whose pursuit and pursuance was at the heart of Nervi's approach, as was a desire to optimise the efficiency; an optimisation of the financial efficiency, the material efficiency, the procedural efficiency, the practical efficiency, the service efficiency, the environmental efficiency, et al, an optimisation of building and buildings of as unignorable urgency in Nervi's 20th century as it is in our 21st. And an efficiency and optimisation which Nervi convincingly argues is related not only to how a construction is physically realised, to the physical process of construction, although that is very important, but also, primarily, to how a project is developed, by the development of an economically valid, solution, for, as Nervi opines, "the strictest economy of execution will never compensate for a poor plan or a mistaken structural solution".23 And, if we follow Nervi, which we don't have to, but let's, it's fun, that necessary efficiency in construction is indelibly related with the development of a structural solution that, in many regards, develops naturally from the physical constraints associated with it's required dimensions and functionality in context of the material: is given through adopting "schemes which best correspond to the function of transferring weights and stresses to the supports and to the foundations by the simplest and most natural method".24

Not that an efficiency of construction, an economic validity, necessarily means a lack of a pleasing formal expression, necessarily means a building devoid of an engaging, interesting, communicative character, necessarily means a cold, geometric, building of the type the inter-War Functional Modernists are regularly accused of advancing; rather, while Pier Luigi Nervi readily accepts that, depending on the skill or otherwise of the individual architect, a, as he terms it, "correct work"25, can be aesthetically inexpressive, he is firmly of the opinion that an efficient construction is a pre-requisite for enabling a pleasing formal expression, for enabling an engaging, interesting, communicative character, and for all arguing that in architecture where "functional, statical, and economical needs are intimately mixed, truthfulness is an indispensable condition of good esthetic results".26 A "truthfulness" that for Pier Luigi Nervi is indelibly linked with efficiency, that "the outward appearance of a good building cannot, and must not, be anything but the visible expression of an efficient structural or construction reality"27. And thus for Pier Luigi Nervi it is and was essential that architecture, in contrast to the accepted convention of recent generations, was planned from the inside not the outside, that rather than designing a building and then considering how to construct it, one started with the construction, started with the structural solution, that the "form must be the necessary result, and not the initial basis, of the structure".28 That, if one so will, for Pier Luigi Nervi form follows function in the sense that the function of a construction is not to collapse. While always allowing for individual artistic freedoms within the technical and material confines.

A shifting of focus from the formal expression to the construction that saw Pier Luigi Nervi directly, if arguably unintentionally, challenge the accepted justification for the existence of architects.

In centuries past architects were also civil engineers: the man, and it invariably was a man in centuries past, responsible for the form was also responsible for the stability, whereby the form had primacy and the laws underscoring the stability were in any case unknown, intuition and experience being all the architects of yore had to work with. Then, and as so oft in human (hi)story, in the middle of the 19th century increasing reliance on science and technology led to increasing specialisation, increasing separation of responsibilities, and increasingly saw the architect become responsible for the form and the civil engineer for the stability, an interplay, a dialogue, between architect and engineer, between art and technology, Nervi argues without which "an architectural design remains incomplete, disharmonic and inexpressive".29 A position that tends to be reinforced, pun again intended, by a cursory survey of the (hi)story of architecture since the middle of the 19th century, by reflections on the importance to that (hi)story of the dialogues between, and amongst a great many others, the engineer Dankmar Adler and the architect Louis H Sullivan in late 19th century Chicago; between the engineer Karl Bernhard and the architect Peter Behrens in early 20th century Berlin; between the engineer Iannis Xenakis and the architect Le Corbusier in post-War France; between the engineer Ove Arup and the architect Peter Womersley in post-War Scotland.

However, for Pier Luigi Nervi this necessary dialogue could either be a cooperation between two or "in the consciousness of only one person"30, and Pier Luigi Nervi, and summarising more than is perhaps prudent, or indeed accurate, was one of the first builders to not only return to intuition and experience in the development of a construction plan, or perhaps more accurately, one of the first builders to consider the results of mathematical calculations and structural theory in context of, as an extension of, subservient to, intuition and experience in the development of a construction plan, and that, not least because he both understood that in terms of new materials traditional analytical methods were bound to lead to discrepancies between practice and theory, discrepancies which, for Nervi, could be best approached through an intuitive understanding of the material based on experience rather than an unquestioning reliance on the math, and understood that the complexity of the theoretical calculations involved in his constructions made coming to a single, definitive, reliable, answer all but impossible, there would always be discrepancies between practice and theory, discrepancies which, for Nervi, could be best approached through an intuitive understanding of the material based on experience rather than an unquestioning reliance on the math. And Nervi was also, ¿therefore?, ¿as a consequence of?, one of the first builders to reconcile the over generations dissociated form-giving and stability-giving responsibilities, albeit, we'll argue, as one of the first to place the primacy on the stability, one of the first to put the technical above the formal, to put engineering above art, in the development process, and thereby enable, force, a re-framing of the question, what is the role and function of the architect in contemporary society? Considerations and questions which, as discussed from The Architecture Machine. The Role of Computers in Architecture at the Architekturmuseum der TU München, become very acute in a (near) future of ever more advanced and autonomous computer technology.

Advanced autonomous computer technology that will also increasingly question the function and role of civil engineers in construction processes. Advanced autonomous computer technology that will, ¿inevitably? see the dialogue between art and technology undertaken not "in the consciousness of only one person" but in the computations of only one algorithm. Advanced autonomous computer technology that will, ¿inevitably?, see the "rapport between building technology and architectural aesthetics"31 become ever more inextricable, see the "synthesis of technology and art"32 in context of architecture Pier Luigi Nervi demanded, strove for and embodied, become ever tighter.

What need will we have for civil engineers and architects in our coming autonomous technological future?

???

A Pier Luigi Nervi helps us all understand that the question isn't new, that the role and function of civil engineers and architects in construction processes and in the societies construction arises from and assists, has been in continual flux since the professions arose, a continual evolution inextricably linked with novel materials and novel technologies, novel materials and novel technologies in context of which the question is framed in our age; and also helps us all better appreciate that for global society it is important that architecture and civil engineering not only seek to fully grasp the possibilities and opportunities offered by the novel materials and novel technologies of our age, to evolve as professions with those materials and technologies, but that in doing so they don't, ignore the path that they, we all, have taken, don't, in their necessary exploration and exploitation of the novel, lose sight of Pier Luigi Nervi's convincing demonstration that the novel is often, ¿always?, most meaningful as an evolution and development of the established in and for a new context and reality.

Happy Birthday Pier Luigi Nervi!!

1Pier Luigi Nervi, Translated by Giuseppina and Mario Salvadori, Structures, F. W. Dodge Corporation, New York, 1956 page 29

2See Claudio Greco, Pier Luigi Nervi. Von den ersten Patenten bis zur Ausstellungshalle in Turin 1917-1948, Quart Verlag, Luzern, 2008, page 21 Other sources claim that on account of father's position with the Italian State Post the young Nervi was raised in several locations. We've been unable to verify that, which is almost certainly because we're looking in the wrong places......

3ibid

4For more on Nervi's time at the Scuola in Bologna and the influence, importance, of Attilio Muggia see ibid page 21ff

5ibid page 39

6ibid page 72

7Gio Ponti, Palazzina al Lungotevere Arnaldo da Brescia in Roma, Domus 37, January 1931 page 15-34

8see Claudio Greco, Pier Luigi Nervi. Von den ersten Patenten bis zur Ausstellungshalle in Turin 1917-1948, Quart Verlag, Luzern, 2008, page 22 FN 10

9Pier Luigi Nervi, Translated by Robert Einaudi, Aesthetics and Technology in Building, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1965 page 23

10ibid page 24

11ibid

12Pier Luigi Nervi, Concrete and Structural Form, The Structural Engineer, Vol. XXXIV, No. 5 May 1956 page 156

13Claudio Greco, Pier Luigi Nervi. Von den ersten Patenten bis zur Ausstellungshalle in Turin 1917-1948, Quart Verlag, Luzern, 2008, page 149

14Pier Luigi Nervi, Concrete and Structural Form, The Structural Engineer, Vol. XXXIV, No. 5 May 1956 page 155-172

15Pier Luigi Nervi, Translated by Robert Einaudi, Aesthetics and Technology in Building, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1965 page 35

16Pier Luigi Nervi's oeuvre is one of commercial and public buildings, of factories, exhibtion halls, banks, aircraft hangers, stadia, bridges, etc.... not that he wasn't interested in residential housing, in, for example, his final 1962 Charles Eliot Norton lecture he talks in despairing tones of how "almost all the efforts of innumerable architects have succeded only in aggravating the vulgarity or, in the best cases, the inexpressivity of these [residential] buildings", of a "banality of the fenestration" and a "substantial mediocrity". (See in Pier Luigi Nervi, Translated by Robert Einaudi, Aesthetics and Technology in Building, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1965 page 183-184.) But as far as we can ascertain he didn't build residential houses, didn't seek to contribute to a development he obviously felt necessary. If that was because of a lack of opportunity, because no one asked him, or because he understood housing as a different domain from that which he specialised in, a specific functionality of typology that he felt too removed from construction, we no know. But we're sure others do.......

17For a list of Pier Luigi Nervi's patents see Claudio Greco, Pier Luigi Nervi. Von den ersten Patenten bis zur Ausstellungshalle in Turin 1917-1948, Quart Verlag, Luzern, 2008, page 283-284

18Although "ferrocement" - cement reinforced with iron - had been known and employed since the middle of the 19th century, in 1943 Nervi was awarded a patent for the "Perfection in the construction of slabs, discs and other reinforced concrete structures", a perfection in which "several layers of metal wire mats are employed which are evenly distributed over the entire thickness of the component", and which through, in essence, increasing the metal content, and form of that metal, in comparison to traditional ferrocement formation increased the stability and flexibility of the reinforced components. With very practical advantages Nervi was very adpet at exploiting. See Patent Nr. 406296 Pier Luigi Nervi, Rome, 15th April 1943. Reproduced in Claudio Greco, Pier Luigi Nervi. Von den ersten Patenten bis zur Ausstellungshalle in Turin 1917-1948, Quart Verlag, Luzern, 2008, page 287

19Ada Louise Huxtable, Pier Luigi Nervi, George Braziller Inc, New Yorl, 1960 page 19 The phrase "still unknown" is particularly pleasing for while reinforced concrete was known before Nervi, he was one of the first to allow it to fully express itself.

20see From the Past to the Present in Pier Luigi Nervi, Translated by Robert Einaudi, Aesthetics and Technology in Building, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1965 page 1-21 The corresponding lecture was held on April 12th 1962 in the Lowell Lecture Hall at Harvard University, see https://www.thecrimson.com/article/1962/4/13/nervi-ties-technique-to-aesthetics-urges/ (accessed 21.06.2022) The four lectures were subsequently published as Aesthetics and Technology in Building.

21Pier Luigi Nervi, Translated by Robert Einaudi, Aesthetics and Technology in Building, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1965 page 5

22Pier Luigi Nervi, Translated by Giuseppina and Mario Salvadori, Structures, F. W. Dodge Corporation, New York, 1956 page 1-2

23ibid page 7

24Pier Luigi Nervi, Translated by Robert Einaudi, Aesthetics and Technology in Building, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1965 page 190

25Pier Luigi Nervi, Translated by Giuseppina and Mario Salvadori, Structures, F. W. Dodge Corporation, New York, 1956 page 27

26ibid

27Pier Luigi Nervi, Concrete and Structural Form, The Structural Engineer, Vol. XXXIV, No. 5 May 1956 page 155

28ibid

29Pier Luigi Nervi, Translated by Robert Einaudi, Aesthetics and Technology in Building, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1965 page 102

30ibid

31ibid page 1

32ibid preface