"So revolutionary his ideas", opined the Austrian state broadcaster ORF in 1969 of architect Hans Hollein, "when he enunciates them they sound like the cosy, cordial habitiere of ages past. His 'schauen se' and 'eeeeeh' conjure up Fiaker, the chatter and gossip on Graben, the Riesenrad, memories of alt-Wien".1

With Hollein Calling. Architectural Dialogues the Architekturzentrum Wien invite one to explore in more detail the vocabulary and articulation of Hans Hollein.......

Born in Vienna on March 30th 1934 Hans Hollein studied architecture at the city's Akademie der bildenden Künste, graduating in 1956, and subsequently spending the greater part of the late 1950s outwith Austria, including acquiring a Master of Architecture at the University of California's newly established College of Environmental Design in Berkeley, before returning to Vienna where in 1964 he received his professional architect's license. Not that a great deal of that which Hans Hollein did had all that much to do with the profession of architecture as understood in 1964 Vienna. Far less in alt-Wien.

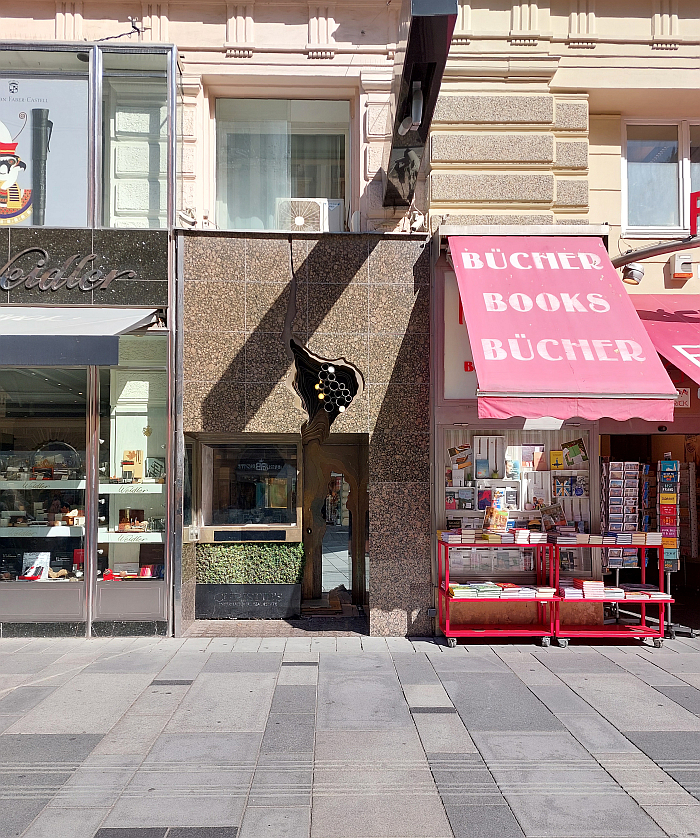

An approach to, an understanding of, architecture that Hollein first publicly expressed through realised projects such as, for example, his shop on Vienna's Kohlmarkt for the Retti candle company, his first commission in Vienna, his first physical contribution to the Vienna cityscape, and a shop which aside from its incorporation of both aspects of the developing concept of retail psychology that made it as much a model of a novel retail concept as a candle shop, and its vast and varied use of aluminium that made it as much a vision of the (promised) coming technological society as a candle shop, and, and as noted from On Display. Designing the shop experience at Design Museum Brussels a space incorporating a sense of borderlessness representative of the hope of the immediate post-War years, also incorporated aspects of Otto Wagner's 1902 Die Zeit office and Adolf Loos' ca. 1913 Kniže & Co menswear store, both works that remind that for all its cosy, cordiality Vienna has a long (hi)story of 'revolutionary' architects and architecture. In addition Hollein designed the entire corporate identity of the store down to the wrapping paper and bags, an indication of his understanding of architecture as more than just the development of a physical space.

And an approach to, an understanding of, architecture also expressed through studies, through (primarily) theoretical projects, such as, and amongst many others, his 1966 proposal for an extension of Vienna University: a television. And thus a proposal indicative of the place electronic media was increasingly taking in society and also of an understanding of the space occupied by humans as being intangible as well as tangible, and also, arguably, certainly in retrospect, a clear prediction of the internet, and online distance learning, and also a reminder of an intrinsic humour in much of Hollein's work. Or his 1965 Minimal Environment, essentially a telephone box in which humans live wearing a space suit, which for all it is, yes, highly improbable and impractical, does encapsulate a lot of Hollein's, then, positions on architecture, on the relationships between constructed space and wider technological and social developments, and for all the need in the contemporary age to move beyond established understandings of architecture; or his 1969 Mobile Office project, an inflatable plastic bubble in which one could sit and work, and which, as previously noted, is a project not only very much of its time, but very, very much of ours.

Late 1960s projects which helped Hans Hollein establish himself amongst the more questioning, challenging, radical, revolutionary, contemporary architecture, architectural theory, positions of the period, and which led to him realising an increasing number of high profile, international, projects, including, and amongst others, the 1977/78 Glassware and Ceramics Museum in Teheran, Iran, a reminder of that period in the 1960s and 70s when Iran, much as Qatar and Saudi Arabia today, increasingly spent its oil revenue on commissioning big name international architects to develop landmark projects, for all cultural and urban planning projects; a housing block on (West) Berlin's Rauchstrasse, his contribution, as noted from Anything Goes? Berlin Architecture in the 1980s at the Berlinische Galerie, Berlin, to the 1984/87 International Building Exhibition, IBA, and which stands today, certainly externally, we know it not internally, as a pale imitation of that which Hollein created; Vulcania - European Park of Volcanism, in Saint-Ours-Les-Roches, France, one of Europe's more individual science centres/theme parks, a, primarily, subterranean structure crowned by an implied volcano cone; or, and returning to Vienna, and for all to alt-Wien, the so-called Haas Haus a work sited diagonally opposite from the city's Stephansdom, and which with its prominent curved glass facade at first appears a glaring, almost deliberately so, contrast to, assault on, Stephansdom, indeed the general location around Stephansplatz, but which embodies a great many of Hollein's positions on considerately combining the new with the existing in urban spaces. That essential, age-old, unending task every generation faces afresh. And, we'd argue, is the roof of Stephansdom any less prominent and vociferous and Bling than Haas Haus's facade?

Alongside his architectural work, or perhaps more accurately, alongside that which conventional language understands as architectural work, for Hollein everything is architecture, everyone architects, Hans Hollein was also active as a writer and educator: in context of the former not only publishing numerous texts but also serving for several years as a member of the editorial team of the Austrian architecture magazine Bau; in context of the latter serving tenures in a variety of positions at institutions such as, for example, the Staatlichen Kunstakademie Düsseldorf, Washington University's School of Architecture or the Universität für angewandte Kunst, Vienna, where at different periods he was responsible for teaching in both the architecture and industrial design schools. An industrial design he also practised, including developing in 1966 the so-called Roto-Desk for Herman Miller, essentially a round desk that revolved, lazy susan-esque, allowing you to spatially organise various projects on the desk and bring them individually to you when needed, if a desk concept which, as far as we can ascertain, never entered mass production. And was also a prolific developer of and designer of exhibitions, over the years creating shows such, for example, MAN transFORMS, the inaugural exhibition of the Cooper-Hewit Smithsonian Design Museum, New York; Traum und Wirklichkeit 1870 - 1930 for the Wiener Künstlerhaus, an exhibition that explored the creative path Vienna had taken before Hollein, and which, potentially, we never saw it, helped place Hollein on that path; or in 1968 developing the so-called Austriennale by way of Austria's contribution to the XIV Triennale di Milano, a presentation which placed at its centre a critical discourse on contemporary mass, consumer society and from which as visitors exited they received a pair of mass-produced plastic glasses coloured à la the Austrian flag, but of which the legs couldn't be folded flat thus leaving one with a problem when they weren't being worn. Which yes does sound like a metaphor. And possibly an analogy.

A wide a varied a career which in addition to many other awards, accolades and honours saw Hollein receive in 1985 the Pritzker Prize, the only Austrian to have been admitted to that sacred architects' Olympia.

Hans Hollein died in his native Vienna on April 24th 2014, aged 80.

As an exhibition Hollein Calling. Architectural Dialogues opens, or at least for us the best place via which to enter Hollein Calling, is with the dozen keywords the curators consider central to approaching the work and legacy of Hans Hollein and which are displayed around the periphery of the exhibition space; keywords such as, for example, Materiality, and its discussion on Hans Hollein's use of material, and for all his juxtaposing of materials to create tension in his works; Art, and for all the manner in which both Hollein's understanding of himself as an artist as much as an architect, and also his friendships with the likes of Joseph Beuys or Claes Oldenburg, influenced his architecture; or References, that central element of architecture and design in the immediate post-War decades, and which the curators argue Hollein undertook less brazenly than many of his contemporaries, rather adopting an approach that saw him "subtly transform and defamiliarize"2 that which was being referenced.

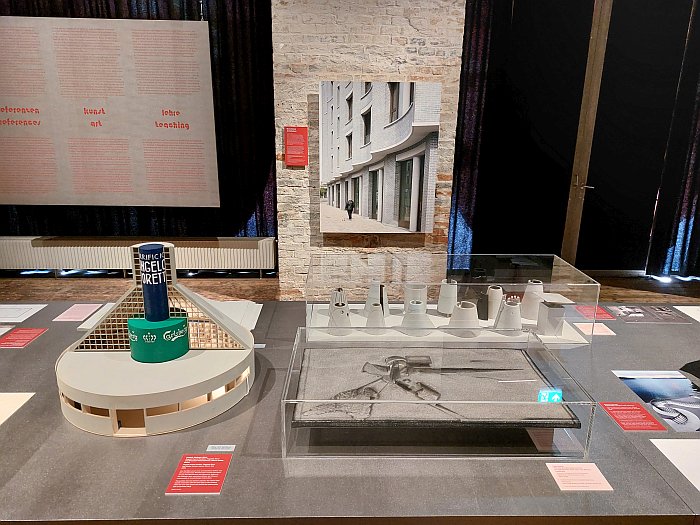

An argument, a thesis on Hollein's work, and eleven other insights of, and discussions on, Hans Hollein and his work, one can then reflect on and scrutinize and further develop in Hollein Calling's presentation of 15 projects from across his career and areas of praxis; each of the 15 set juxtaposed to projects by contemporary architects/practices in which the curators have identified parallels and intersections in terms of realisation, approach and/or underlying position with the Hollein projects.

Thus, for example, Hollein's Städtisches Museum Abteiberg, an art museum in downtown Mönchengladbach whose exterior, its setting on the hill, its interaction with the locality, is as much a component of its being as is its interior, an interior based around a series of square spaces diagonally linked thereby disallowing a straight movement through the space, is juxtaposed in Hollein Calling with Berlin based pratice Kuehn Malvezzi's PHI Contemporary arts centre in Montreal and Brussels based OFFICE Kersten Geers David Van Severen's Campus RTS in Lausanne; or Hollein's Volksschule Köhlergasse in north-west Vienna, a composition of a variety of structures that implies more a town than a school and where in response to the spatial challenges of the site sections of the roof are employed as public spaces is set beside Antwerp based Bovenbouw Architectuur's Community Centre in Edegem, Belgium, and the Smithfield Market project in Birmingham by David Kohn Architects, London; or Hollein's Media Lines project for the 1972 Munich Olympics, a project which saw a series coloured modular metal pipes run through the Olympic complex, a project that was on the one hand an artistic intervention in the space and on the other the functional means for transporting water, cables, ventilation etc across the site while also providing support for loudspeakers, lighting etc, a project which may very well have influenced Günther L. Eckert in the development of his Kontinuum, lest we forget Eckert also contributed architectural projects to the Munich Olympic site, but which in the Architekturenzentrum Wien is presented alongside, amongst other projects, the Student City Campus in Tirana by Milan based baukuh.

Albeit a presentation which through its relative brevity, its almost-but-not-quite silence, on those projects by the collocutors, those projects juxtaposed with Hollein's, forces you to seek to stimulate the dialogue of the title, forces you to try to bring Hollein and the contemporary architects/practices in dialogue with one another. Which, no, isn't cruel, or cheeky, or lazy, but rather through forcing you to do the work enables one to approach a more durable appreciation than would be the case if you simply read something, forces a deeper discourse on your part with both the Hollein projects and that with which they are juxtaposed, demands greater care in your analysis and also, potentially, hopefully, leads you to pose questions of either Hollein's work or the juxtaposed projects that you may not have had you been spoon fed, and thereby to arrive at insights that would otherwise have been inaccessible. And also underscores that Hollein Calling isn't the sort of exhibition that one strolls through in half an hour and leaves with a new favourite work, but rather is an admonishment, an invitation, to engage more with Hans Hollein, an invitation to start a deeper conversation with Hans Hollein. An invitation which is, arguably, exactly what any architecture exhibition should be, and which if they are can help one reframe the old problem of presenting architecture at the museum scale: don't bother presenting it but rather initiate a dialogue in such a manner that you actively encourage the viewer to continue it themselves later. Something Hollein Calling does very neatly and satisfyingly.

And an invitation which if accepted the exhibtion catalogue with its extended interviews with the 15 collocutors is an excellent place to start, not least because, as one discovers, the dialogue isn't always as strong as could be implied simply through viewing the exhibition: Pier Paolo Tamburelli from baukuh, for example, making clear that for him there is no real dialogue between Student City Campus and Media Lines, other than both are public spaces.

Not that such in any way detracts from Hollein Calling, in any way invalidates Hollein Calling, it doesn't; for as an exhibition Hollein Calling isn't about establishing the directness of the dialogue, isn't about establishing Hans Hollein as the defining author of contemporary architecture, that voice of which contemporary architecture is an echo, for he's not. Much more Hollein Calling is about offering an alternative perspective on the work and positions of Hans Hollein, about providing an alternative context and framework in which to consider him, about viewing his work simultaneously with contemporary projects in which parallels and intersections can be identified, and then seeing where that dialogue takes you.

One shouldn't engage in dialogue to confirm your position as correct, despite what contemporary convention, and social media, may indicate; rather one should engage in dialogue to test your position, and if necessary to help you move towards a new position. Just ask Socrates.

An open, accessible, and clearly comprehensible bilingual German/English presentation which via photos, plans, models et al also very neatly discusses the development of the Hollein projects, that dialogue Hollein had with himself, and with his team, and clients, during the development of the projects, for all that it is about stimulating dialogue Hollein Calling is also a very satisfying, a very welcome, and entertaining introduction to Hans Hollein, an architect, a creative, whose importance and relevance today isn't reflected in his quasi-annonymity in contemporary popular discussions on post-War architecture and design, a creative who, as we opined in context of his high visibility in Everything at Once: Postmodernity, 1967–1992 at the Bundeskunsthalle, Bonn, is all too often overlooked by the popular collective memory. But a creative who, hopefully with the ever increasing distance to the more 'revolutionary' days of his career, we can all now begin to engage with on a more subjective, open, unprejudiced manner, for as Hollein Calling allows one to appreciate for all his revolutionary spirit Hans Hollein's was almost always an accessible, polite, expression of that revolution; or put another way, Hollein was a revolutionary with whom one could and can enjoy a Wiener Melange. Or perhaps a Kaffee verkehrt is more appropriate.

And after having viewed Hollein Calling, having shared a metaphoric Kaffee verkehrt, and having instigated a dialogue, with Hans Hollein, you can take yourself out into alt-, and jung-, Wien, with spirits and perspectives refreshed, and view those Hollein works that can still be found around the city; can go outside and continue your dialogue with Hans Hollein on the streets of Vienna. Can skip from the Architekturzentrum's home in the MuseumsQuartier down past the Hofburg, past Loos's eyebrow-less house and into Kohlmarkt with the former Retti store3 with which Hollein's career as a built architect began, and also the early 1980s Schullin II jewellery store, before turning into Graben where amongst the chatter and gossip of tourists and locals stands the Schullin I jewellery store from 1972-74 with its 'cracked' facade exposing brass pipes for the air-conditioning system, a 'cracked' facade reminiscent of a geological fault opening, exposing as it does the inner layers of the earth, a 'cracked' facade that is very deliberate, very Hollein, and, as one learns in Hollein Calling, very methodically designed for function and decoration. And a Schullin I jewellery store which stands, or which at least stood when we were there, empty. Looking very sorry for itself. The fake plastic hedge attached to its facade not really helping. Although it may have amused Hans Hollein. And an empty unloved key work in Hollein's oeuvre which helps underscore the contemporary reception of his work by those tourists and locals who wander past it everyday. Were it a Fiaker or the Riesenrad or a Habsburg residence, everyone would taking photos of it. But its not, its an early 1970s work by Hans Hollein. And for all Hollein may have conjured up alt-Wien when he spoke, his architectural vocalisations still haven't necessarily found their place in the Wienerisch dictionary.

Thoughts you can carry with you from Schullin I to the corner of Graben and Stephansplatz as you view Haas Haus in context of its surroundings, aware as you now are of the changes that have been made to the exterior which have altered the context and thereby changed that dialogue Hans Hollein so carefully, cautiously, sought to develop between Haas Haus and its surroundings. Try changing something on Stephansdom and you'll soon have popular protest against you, try to change something on a late 1980s work by Hans Hollein and most people don't notice.

Much as they don't notice the single palm tree a few doors down from Haas Haus, next to the entrance to Stephansplatz underground station, a solitary symbolised palm tree which indicates the building once housed the city centre branch of the Österreichisches Verkehrsbüro, the Austrian Travel Agency, one of Hollein's more overblown, as in out-of-control, works; and which today is a private travel agents, which, if your cheeky enough, you can enter, and where, in the back of the shop, stands an original grove of metal palm trees as planted by Hans Hollein. Thoroughly untroubled by the mass of tourists gazing up at Stephansdom.

And as you linger on the edge of Hollein's Viennese oasis, trying to imagine the space in its long since lost full effect, you know perfectly well that if the metal palm trees had been associated with a Habsburg, had been a component of alt-Wien, the building would have a plaque on it, and four Austrian flags, announcing its importance. But not late 1970s metal palm trees. Or glass facaded monoliths. Or small jewellers with a 'cracked' facade. They get ignored, changed, occasionally knocked down.

And that, arguably, for no better reason than we don't understand them, don't understand what they are telling us. And so ignore them, consider them unimportant. That long-standing human condition of not recognising the importance of breaking down barriers to communication, of not appreciating that just because you don't understand something doesn't make it wrong; of the human species being collectively blind to what you can learn if you talk with those you don't understand rather than simply dismissing them and denigrating their position and assuming you know better. Which, yes, does sound like a metaphor.

Exhibitions such as Hollein Calling should help change that. Certainly in terms of Hans Hollein. If not necessarily in context of society's larger malaise. And that not least through the manner in which it explores, elucidates and introduces Hans Hollein, the manner in which it opens perspectives on Hollein beyond those in which he is normally to be found, enables new perspectives on Hans Hollein through altering the approach to his works, his positions and their expressions: that all important changing of perspective that is central to any meaningful dialogue. Again, just as Socrates.

And thereby Hollein Calling can not only help us all to better approach a Hans Hollein, but also allow us all to approach better appreciations that for all the cosy, cordiality of alt Wein, it was also once an unfamiliar language, was once something far removed from the accepted and conventional, was something revolutionary, that only slowly over time became vernacular. A vernacular that always has, and always will, always must, evolve. That while one can conjure up the past, one should never remain in it.

Hollein Calling. Architectural Dialogues is scheduled to run at the Architekturzentrum Wien, Museumsplatz 1 im MQ, 1070 Vienna until Monday February 12th.

In addition a catalogue featuring interviews with the 15 collocutors and the 12 keywords is available.

Full details, including information on the accompanying fringe programme, can be found at www.azw.at

1Das österreichische Portrait: Hans-Hollein, ORF, 07.12.1969 On show in Hollein Calling, but also available on Vimeo via Architectural Theory Quote ab ca 01:10 "schauen se" and "eeeeeh" are spoken by Hollein, we may very well have misspelt them. Apologies

2Curator's statement in exhibition and in the exhibition catalogue

3We're going to be honest, we didn't see the former Retti store. Apparently it is still there, has just finished a refurbishment. But we didn't see it. How we missed it we don't know, its facade is aluminium. There may however have been a neighbouring building being renovated that may have confused us. We'll be back in Vienna soon and will look again.......