The Tube. An Architecture for Conceivable Times at the Werkbundarchiv – Museum der Dinge, Berlin

“If we want to survive, if we want to reach the next level”, postulated the German architect Günther L. Eckert in 1980, “we simply have to risk the impossible. It is too easy to invest only in common logic and to dismiss everything that does not have these specific characteristics, everything that encroaches into the incorruptible dimensions of creative self-consent”.1

Günther L. Eckert’s “impossible”, his distancing from “common logic”, his encroaching “into the incorruptible dimensions of creative self-consent”, was the so-called Kontinuum, Continuum, a 250 metre diameter tube which formed a complete, unbroken, circle around the globe, constituted a Kontinuum around the globe, and in which all humanity was to live.

With the exhibition The Tube. An Architecture for Conceivable Times, the Werkbundarchiv – Museum der Dinge, Berlin, introduce Eckert’s Kontinuum and thereby allow space for reflections on not only architecture and the built environments we create for ourselves, and the whys and wherefores of those environments, but also on the possibilities for the future of both human societies and the natural environment on which we all depend.

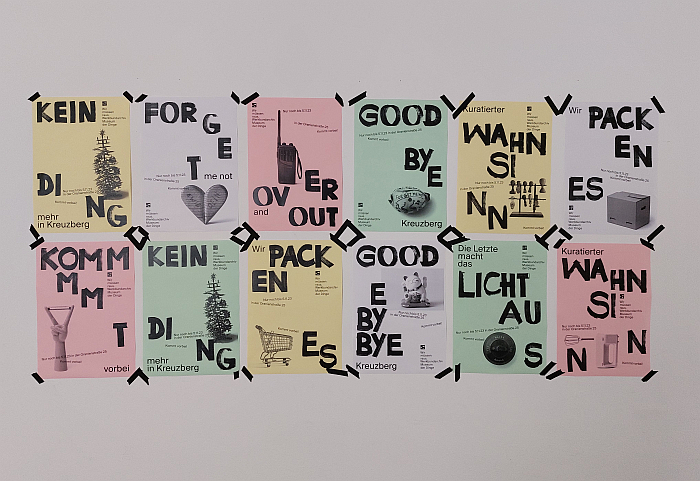

And an exhibition on a Kontinuum that is also the last Werkbundarchiv – Museum der Dinge exhibition in their long-time home in Berlin-Kreuzberg, marks the end of their continuance in Berlin-Kreuzberg, before their imminent, involuntary, investor enforced relocation…….

Born in 1927 in Weiden, Germany, Günther Ludwig Eckert studied architecture at the Akademie der Bildenden Kunst, Munich, before establishing his own office in the Bavarian capital in 1954, from where, alongside realising numerous architecture projects, including a great many student residential blocks, and also contributing a high-rise apartment block and a Mensa to the 1972 Munich Olympic Village, he also developed a self-contained modular plastic bathroom unit and a prefabricated, modular construction system.

And in the late 1970s began developing his Kontinuum, his “conversion (in the sense of a transformation for the attainment of more favourable conditions), which through technology, makes possible the better preconditions for life and removes the worldwide inequality; or even more greatly desired: forces the third great evolutionary leap on a broad basis”. The first two “great evolutionary leap[s]” being, according to Eckert, the earliest humans beginning to walk upright on two legs and the development of language. And a third evolutionary leap necessary because, according to Eckert, the “semi-random evolution” the human species was undergoing “at some point will (inevitably) exhaust itself”, will “reach a point where it can no longer articulate itself (similar to the fate of Neanderthals). Therefore, it would be desirable that an evolutionary process, by chance of an urgent necessity, would generate a more open human aptitude”. The Kontinuum was Eckert’s context to develop the necessary evolutionary “pressure” for that “evolutionary process”, and therefore induce “that third critical evolution, which will hardly be an anatomical evolution, but primarily an ethical/cognitive one”. An evolution which will allow the human species to “evolve into that sustainable basis … where many and nuanced commonalities facilitate mutual understanding and allow the necessary insight, insight into our environment and insight into ourselves, the compulsion to think and feel our way to the causes with gapless accuracy”, and a Kontinuum as a “rebellion of head and soul against the terrible experiences of an egoistic world”, a “Kontinuum as a construction for a meaningful destiny”, a Kontinuum as “a means for the senses [that] can be a method which achieves the better result for the totality”. “For what kind of future would it be if it did not become effective for mankind as a whole?”

Or put another way, Günther L. Eckert’s Utopia.

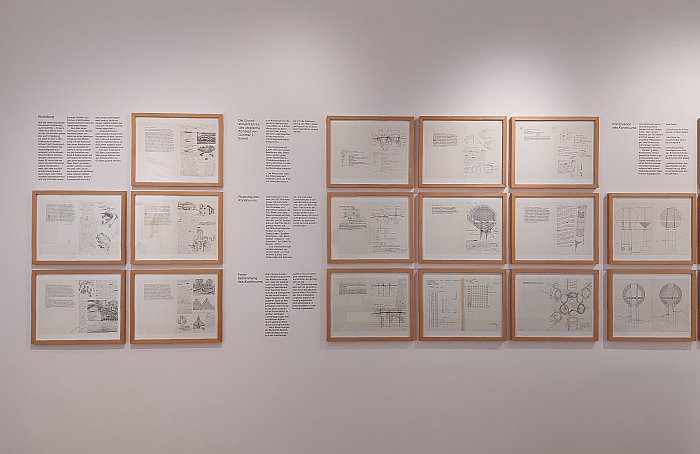

Pages from Günther L. Eckert’s text describing his Kontinuum, and why his Kontinuum, as seen at The Tube. An Architecture for Conceivable Times, Werkbundarchiv – Museum der Dinge, Berlin

A Utopia one gets the impression Günther L. Eckert very much appreciated it was, at one point, for example, he regrets that “we do not seriously develop more and much more expansively the utopian”, and elsewhere defining the earliest Neanderthals’ decision to leave their caves and construct their own homes as “certainly very utopian”, which is an interesting perspective from which to view that stage on the path to contemporary humans and human societies. In addition he makes reference in the introductory chapters of the text in which he presents his Kontinuum to numerous, for want of a better phrase, utopian urban planning projects, primarily one notes from the 1960s, which may give an indication of how the earliest thoughts on the Kontinuum arose, including, and amongst others, Paul Maymont’s 1960 Vertical Cities with their layering of modular units either upward into the sky, or downwards into the Earth; Hal Moggridge’s 1968 Sea City with its concrete and glass islands; or, and staying at sea, William Katavolos’ 1960 Organics which proposed, essentially, growing cities from oil based synthetics which then float on the sea, and which sounds a bit like living on our contemporary marine garbage patches. A solution which, we’re fairly certain, Katavolos would not approve of. Albeit Utopias Eckert is critical of for a number of reasons: Maymont’s because its content is “old-fashioned”; Moggridge’s because it is “no more than the conventional reclamation of land for construction”; Katavolos because he ignores “the principles of social order”.

Utopian urban planning projects which also populate the opening chapter of The Tube. An Architecture for Conceivable Times; an opening chapter which takes you on a brief tour through the (hi)story of Utopias starting from Thomas More’s 1516 Utopia, that work that arguably gave the concept its name and many of its enduring principles and perspectives, and moving on over the likes of, for example, Richard Buckminster Fuller’s City of the Future, Kisho Kurokawa’s Nakagin Capsule Tower, Tokyo, or Masdar City in Abu Dhabi by Forster & Partners, a Utopia currently under construction. Which is an interesting and thought provoking phrase. And also including several projects which, as with Eckert’s Kontinuum, are based on a continuous line: Arturo Soria y Mata’s 1882 Linear City, Edgar Chambless’ 1910 Roadtown, Superstudio’s 1969 Continuous Monument or The Line in Saudi Arabia, the latter a project still in development which has more than a few similarities with Eckert’s late 1970s Kontinuum, albeit a project proposed in a very different context and from very different motivations. If one that poses similar questions. Both of itself and human society.

A Kontinuum presented in the Werkbundarchiv – Museum der Dinge as a 250 metre diameter tube which…. no, not really… although that would be fun… a Kontinuum presented in the Werkbundarchiv – Museum der Dinge as selected pages from Günther L. Eckert’s manuscript, a selection of pages that allow for an introduction to topics such, for example, the form and construction of the Kontinuum, the materials of the Kontinuum, the path the Kontinuum was expected to take round the globe or details of life within the Kontinuum including descriptions of the six types of accommodation modules that would be available, such as, for example, the Pneumatic in which one is transported via “Pneumas with moving air”, a nod not only to the philosophy of Greek Antiquity but the predictions of a Marcel Breuer; the Thermodynamic in which spaces are defined by “coloured fog zones” in conjunction with, for example, music or smells, and which has interesting similarities to the sort of interiors a Verner Panton envisaged; or the Acrylic, a synthetic plastic space that can be continually reshaped and reformed with the aid of, essentially, a clothes iron, and a concept which not only fits in with the limitless possibilities of plastics of the period, and the wondrous democratic future synthetic plastics would bring, but also sounds like a transformable, responsive housing concept well worth pursuing. And thus a presentation which offers an introduction to Günther L. Eckert’s positions and visions. And an introduction to Günther L. Eckert’s Kontinuum.

A Kontinuum juxtaposed in The Tube not only with the aforementioned examples of other proposed, and realised, utopian urban planning projects but also by a vitrine presentation of a selection of academic and literary explorations of and position on Utopias, including, for example, various works on Atlantis, an investigation of August Hermann Francke’s Schulstadt, School City, in Halle, Richard Fairfield’s The Modern Utopian: Alternative Communities of the ’60s and ’70s with its analyses of post-War US counter culture Utopias, Karel Čapek’s R.U.R. a Utopia that goes badly wrong for humanity. Very badly wrong. Or William Morris’s 1890 News from Nowhere, a Utopia that for all it very clearly greatly appealed to Morris, and for all the time we have for Morris and his opinions and positions, sounds absolutely awful. Or at least large sections of it do. News from Nowhere You Would Ever, Ever Want to Live, being its title round our way.

And thus a selection of actual reflections on actual attempts at building Utopias, and literary imaginations on Utopias, which remind us all that, and as noted from Wohnen at the Klassik Stiftung Weimar, more specifically in context of Martin Maleschka’s installation Wohnmaschine 4.0, Utopia isn’t always automatically Utopia. It’s much more complicated than that. And also reminding that Utopia and Dystopia aren’t that far removed from one another. And are readily interchangeable. See also synthetic plastics. And R.U.R. And The Line.

Reminders Günther L. Eckert’s Kontinuum also stimulates.

We’re admittedly unsure in how far Günther L. Eckert actually genuinely believed placing all humanity in a 250 metre diameter tube circumferencing the earth at an altitude of 350 metres above sea level was a good idea, and it isn’t a subject that is approached in The Tube; however, in many regards it’s also not that important.

Because, very clearly, very obviously, instantly so, placing all of humanity in a 250 metre diameter tube circumferencing the earth at an altitude of 350 metres above sea level, is a truly ridiculous idea, bananas can’t quit begin to properly describe it, and quite frankly if that’s where we as a species are heading then better to end the experiment humanity here and now; however, much as, for example, Fritz Haller’s various and varied space cities or Richard Buckminster Fuller’s plan to place a transparent dome over Manhattan as if it were cheese platter, or Archigram’s 1964 Walking City, a city which walks, or runs away depending on your viewpoint, and which we last met in context of the exhibition Die Stadt. Between Skyline and Latrine at the smac – Staatliches Museum für Archäologie Chemnitz, with its various and varied reflections on city’s as both real and invented, tangible and imagined, thinking about such extreme solutions and defining and visualising such extreme solutions as actual practicable feasible projects, is also an interesting, informative, and important, task in context of questioning contemporary life on earth, and of seeking alternative ways forward “effective for mankind as a whole”; of finding paths to the problems rather than to the symptoms of the problems of contemporary society and thereby finding meaningful, future-resistant, solutions. And reminding us all that while the solutions to our problems can be extreme, there are invariably also much simpler solutions. Or are once one understands what needs to be done.

Or put another way, the solutions to the problems of society are rarely to be found in architecture; but architecture can be a meaningful method of approaching those solutions, a meaningful tool for approaching those solutions. If one poses relevant, carefully formulated, questions.

A position Günther L. Eckert very much represents with his Kontinuum, quite aside from, and amongst other examples, noting that “our relationships to ourselves and our environment have become much more complicated, so we will also have to come to more complicated insights in order to come back to an understandable development”, more generally states that, “the basic question about the Kontinuum will not be: is this very technical structure producible? … It is producible”, something the presentation in the Werkbundarchiv – Museum der Dinge, and Eckert’s own detailed calculations, tend to confirm, much as with Archigram’s Walking City, Buckminster Fuller’s dome or Haller’s space cities, Eckert’s Kontinuum is “producible”; rather for Eckert “the question will be whether we are able to deal with the unconstraint in the Kontinuum, to deal with it without regimentation, without manipulation, without dictation, thus: totally self-responsible? Have we already reached the end of our possibilities of self-responsibility?”, while life in the Kontinuum will be possible, the question of “whether we can behave in it will not just be a matter of good will. It will require a radical cognitive reorientation.” ¿But will that happen? ¿Will we be able to comprehend that? ¿And act on that comprehension? ¿And what is necessary for us to be able to “behave” on earth, outside the Kontinuum, in the here and now?

The Kontinuum is technically feasible, but the environments humans inhabit aren’t just technical, they are also social. ¿Is the Kontinuum socially feasible? ¿And if not why not? ¿And is that the correct question?

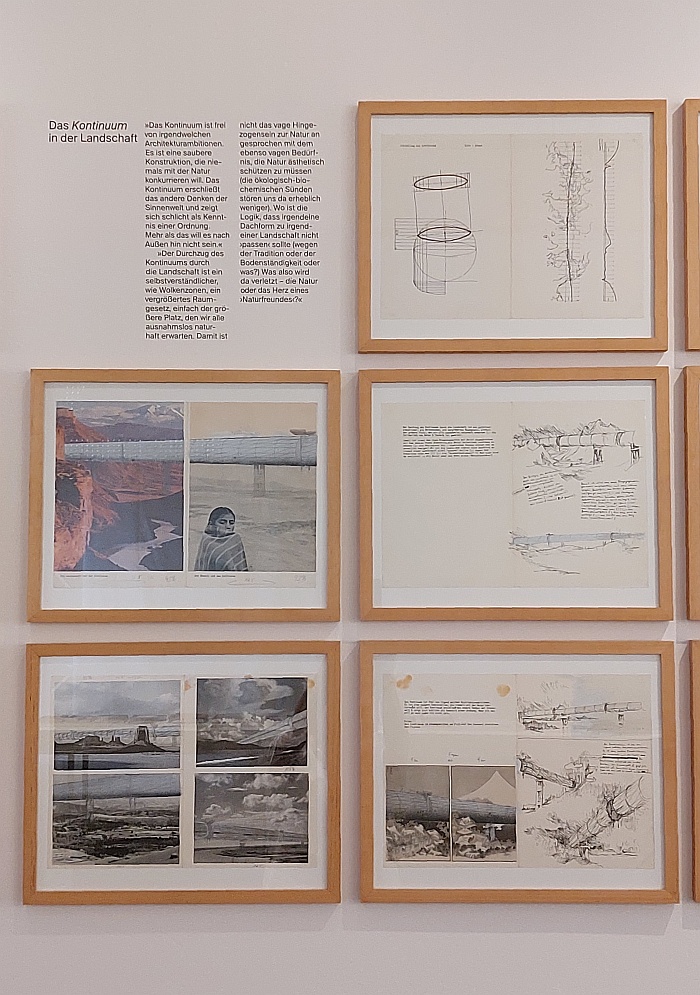

Photomontages of the Kontinuum passing through the global landscape, The Tube. An Architecture for Conceivable Times, Werkbundarchiv – Museum der Dinge, Berlin

For all that Günther L. Eckert’s text is primarily concerned with the physical and technical details of the construction, with proving “it is producible”, it also offers insights into the questioning of contemporary global society that led him to consider housing all humans in a 250 metre diameter tube circumferencing the earth at an altitude of 350 metres above sea level, led him to divert from the “common logic” that says don’t, whatever you do, house all humans in a 250 metre diameter tube circumferencing the earth at an altitude of 350 metres above sea level.

A questioning of contemporary global society that is, it’s fair to say, highly polemic, in his text he rails against an awful lot of things, pretty much everything to be honest, and as such it must be approached with a lot of caution, particularly in the 2020s, one must always remember it’s not a truth, it’s an opinion, an opinion from the 1970s; however, if approached with the necessary distance and critical challenging, Eckert makes a few interesting and informative points and poses several still very relevant questions, including, for example, and amongst others, questioning where consumerism will take us, that question the Club of Rome had so graphically formulated in 1972, and a questioning Eckert frames in context of, amongst other statements, denouncing consumer production at an “unrestrained wildness far beyond our needs”, and “selfish economic interests with their double morality”, which sees us “continue to exploit the Earth without restraint”, and thus one of the sources of the environmental damage Eckert sees human society inflicting on the planet, damage through humans the Kontinuum should also protect Earth from. ¿Where would we be today had it been built? And also questioning the militarisation of a period where, for Eckert, “we stand, abysmally deficient with the bomb ready to go off”, a period of “merciless images of humanity (humanity at the fuse of the nuclear overkill)” a period of “regulation by bomb”: “we can’t remain a species that periodically and with increasing sophistication decimates itself through war and then recovers”, he implores. ’twas, lest we forget, a period lived in the shadow of the very tangible nuclear tensions of the Cold War. But could also be tomorrow.

And, we’d argue, a questioning of consumerism, ecology, geopolitics, power, egotism, amongst other topics, that fuse together in the observation that, “we have been given knowledge and can use it to bring about our own demise”. A reality, and a predilection for living precariously on account of our free decisions, that we continue to demonstrate. And apparently delight in. Or what do Alexa and Siri think?

A selection of academic and literary explorations of Utopia, as seen at The Tube. An Architecture for Conceivable Times, Werkbundarchiv – Museum der Dinge, Berlin

But for all Günther L. Eckert rails against and questions architecture and architects: rails against and questions an architecture “afraid of future realisations, because it hides itself so helplessly behind old and fashionable architecture”, against the “career architecture (the unrestrained “self-promotion” of the architectural artist)”, against “architecture as the aesthetic jealousy, and man remains outside”, against “fashionable pictures” in high-gloss magazines, against “the deadly course of the architectural milieu (the milieu trend in postmodernism)”. If he knew where Postmodernism would go in the 1980s you imagine he would have railed even more.

And an architecture he compares unfavourably with Bauen, building/construction, that “history of human needs born from desire from well-being”, a Bauen he very much approves of, and in which context he demands, “a reorientation away from the efficacy of architecture and its conservative beauty ideology and its illusory interpretations towards the communicative, intrinsic characteristic of an inseparable relationship to the building (building as the natural form of meaning, not of formal aesthetic expression; the gibberish of a visual language where it does not even matter any more whether its about the speculative profit hunger of unscrupulous property speculators or about the aesthetic pleasure of an affectionate architect’s vanity). Both are self-serving, believing only in themselves and completely lacking in a relationship to human beings, on the contrary: they downright provoke the human being, as motif, as a staffage, as a delightful movement, as a splash of colour.”

Really not that keen on architecture and architects; or perhaps more accurately, not at all happy with where architects had brought construction through architecture, for Günther L. Eckert, “architecture should be justified more deeply and not only as a question of style or a question of housing procurement or as another satisfaction of needs”. Nor, one can summarise, only a question of ego, vanity or profit.

Thoughts which lead you out of the Kontinuum, out of the Werkbundarchiv – Museum der Dinge’s temporary exhibition space and into the sprawling complex at Oranienstraße 25 the Werkbundarchiv – Museum der Dinge have called home for the past 15 years. And which they assumed would also form a type of unbroken Kontinuum, until property developers bought the building and terminated all leases.

We no know what the new owners of the sprawling complex at Oranienstraße 25 have planned, but it’s pretty safe to assume it won’t include a cultural institution that allows for the presentation of subjects all too regularly and quickly skipped over by larger institutions nor which houses a collection of objects and archive material which can contribute to helping advance understandings of the path European society has taken thus far, of the routes European society have taken and thereby enabling us to better avoid the pitfalls and traps of the past. Nor will it, we assume, offer space for the mix of commercial, cultural and social concerns who called Oranienstraße 25 home and who have now been strewn across the city.

But what it will be is something inserted roughly, forcibly, into a hole it itself has hewn in an existing community, a community that over the years has developed and evolved, a process of communal, social development and evolution through exchange and interaction and experience which, in many regards, can be considered as a basis for the “ethical/cognitive” development and evolution Günther L. Eckert understood as necessary if the human species was to survive. An expression of “the principles of social order” he accuses a Katavolos of ignoring, and which is something architects, and all other Utopians, invariably leave to one side. And something property developers rarely, if ever, care about. And which is, in many regards, the challenge set by Eckert, is, an argument can be constructed, that which he seeks to force in his Kontinuum. And that which happens without a Kontinuum, but which a Kontinuum helps one to focus on, and to appreciate as more important than developing and evolving ever greater physical power or ever greater financial power or ever greater egos.2

And which is one of the reasons why the building renewal projects of the likes of Lacaton & Vassal, Druot and Hutin are so interesting and important, allowing as they do, empowering one could argue, a building, its internal life and its external relationships to remain largely unaffected by refurbishment and regeneration, doesn’t uproot and replace, but allows for a continuation in more favourable contexts, structures and materials. Allows a social Kontinuum.

Or put another way, sustainability in architecture and urban planing isn’t just an ecological question, isn’t alone one of building norms and energy certification and green roofs, it’s also an economic and a social question. The Kontinuum is technically feasible, but the environments humans inhabit aren’t just technical, they are also social. ¿Are contemporary cities socially feasible? ¿And if not why not? ¿And is that the correct question?

Which isn’t an argument against urban development, far from it, but is an argument against an urban development that doesn’t occur in conjunction with the local community, is an argument against an urban development from outwith for poorly publicly defined, or understood, but invariably purely financial, reasons, ¿why must everyone leave Oranienstraße 25? ¿where is the necessity?, is an argument against an urban planning that understands buildings and open spaces in financial terms and architectural terms and not in social, cultural, environmental, emotional terms. Or is the only true Kontinuum capital? And if it is, what does that mean for the future evolution of humans, individually and collectively? Or as Günther L. Eckert asks, rhetorically, “What does man gain in the profit of the profiteers and the power struggles of the powerful? (Probably the short end of the stick)”.

A question we’ll leave here, not least because we’re fairly certain it will also be approached in the forthcoming exhibition Profitopolis, the planned inaugural exhibition in the Wekbundarchiv – Museum der Dinge’s new home at Leipziger Straße 54, Berlin-Mitte.3

Not an exhibit, but certainly informative: packing crates ready to be moved out of the Werkbundarchiv – Museum der Dinge

A bijou showcase with an expansive vista, and, yes, a very text heavy presentation, but then there is sadly no space for the recreation of parts of the Kontinuum, fun as that unquestionably would be, but if any museums with very, very large exhibition halls are planning a ‘Utopia’ exhibition it may be worth considering, The Tube can do no more than make you aware of Günther L. Eckert, his view of the world in 1970, and his Kontinuum and seek to stimulate you to undertake more research and for all to undertake more critical thinking on architecture, urban planning, society and Utopia on your own. A task it performs very pleasingly and satisfyingly, and that not least through the associated re-issue of Eckert’s text in a bilingual German/English publication.

And thereby allows space for reflections on the role of Utopias not as actual destinations, not as a Masdar City, but as spaces for theoretical reflection on the societies we actually want; for reflections on an inconceivable future such as Eckert’s conceivable Kontinuum that demands a questioning of the architecture and urban planning we need for the conceivable times of the exhibition title, those times that we live in and those which will come in the immediate future and in time will lead to the inconceivable distant future we normally plan for but can in no sense predict. A demand to consider the possibility of extending the foresight and perception of architecture and urban planning through a shortening of the architectural and urban planning gaze; a demand in many regards also discussed by Studio Högl Borowski’s project 1 M² at Vienna Design Week 2023. And in a Lucius Burkhardt‘s many arguements against the Gesamtplan, the long-term master plan, of urban planning.

A Utopian space (¿in a coming Dystopian space?) in which to reflect on Eckert’s arguments on “how badly do we formulate the things that tear our breast” and that “we cannot hope to solve our problems within the means of conventional thinking”, while also being very aware that just because something is feasible, producible, doesn’t mean it is desirable or helpful. Thus a Utopian space the planners of The Line really should visit. And whoever it is at Amazon whose convinced we need delivery drones.

But for all a Utopian space, a ridiculous, bananas, feasible, producible Utopian space, in which to begin to approach much better appreciations of Günther L. Eckert’s late 1970s opinion that, “if we want to survive, if we want to reach the next level we simply have to risk the impossible”, and cease our “disqualification of the conceivably possible”.

Whereby “impossible” and “conceivably possible” needn’t be a 250 metre diameter tube circumferencing the earth at an altitude of 350 metres above sea level; but a 250 metre diameter tube circumferencing the earth at an altitude of 350 metres above sea level can help us formulate and define such terms. And thereby approach them.

The Tube. An Architecture for Conceivable Times is scheduled to run at the Werkbundarchiv – Museum der Dinge, Oranienstraße 25, 10999 Berlin until Sunday November 5th

Then it’s lights out … until the re-opening in Spring 2024 at Leipziger Straße 54, 10117 Berlin.

Further details, including on the re-issue of Günther L. Eckert’s text, can be found at www.museumderdinge.org

And all the best to the Werkbundarchiv – Museum der Dinge with the move. We’ll see you in Mitte in the spring. ✊

Arguably our favourite exhibit in the Werkbundarchiv – Museum der Dinge, and no, not just because its been randomly fixed at the top of a wall…….

1. and all other quotes unless stated from Werkbundarchiv – Museum der Dinge & Michael Fehr [Eds.], Günther L. Eckert, Die Röhre. Eine Architektur für denkbare Zeiten, 2023 While we generally use Michael Fehr’s translations of Eckert’s original German text, we do occasionally use our own

2. Yes, there is the possibility that the new residents of Oranienstraße 25 will form a connection with the community and over time evolve to develop as part of that community much as has happened over the decades past, we’re nor ruling that out; in how far the occurs depends to the degree to which the new residents of Oranienstraße 25 understand themselves as owing or inhabiting the space. How much interest they have in the world outside their expensive four walls.

3. In addition, on account of the enforced relocation the Werkbundarchiv – Museum der Dinge will be closed for six months which is a long time for a museum to be closed. And an even longer time for an archive. And an enforced closer which means that simultaneously the Werkbundarchiv and Bauhaus Archiv will be closed, two of the more important sources for information on the early 20th century in Germany. And home of some important sources for more nuanced reflection on Utopias of the past, Dystopias of the past and thus to the more nuanced reflections on the way forward that Günther L. Eckert admonishes is the only hope for the survival of humanity and the Earth.

Tagged with: Berlin, Günther L. Eckert, Kontinuum, The Tube. An Architecture for Conceivable Times, Utopia, Werkbundarchiv – Museum der Dinge