In context of the 1923 Bauhaus exhibition in Weimar, that first wide-ranging presentation of the school, its work and its understandings of itself and the world in which it existed, the institute presented with the Haus am Horn by Georg Muche and its interior, furniture, fittings and accessories by the likes of, and amongst others, Erich Dieckmann, Alma Buscher, Otto Lindig, Benita Otte or Marcel Breuer, a synopsis of the prevailing understandings of and positions to domestic arrangements and domesticity amongst the Weimar Bauhäusler.

With their 2023 theme year Wohnen the Klassik Stiftung Weimar take us all back to a century and a bit before Haus am Horn and to understandings of and positions to domestic arrangements and domesticity in the late-18th/early-19th century Weimar of Goethe, Schiller, Wieland, Herder et al.

And also consider possible future understandings of and positions to domestic arrangements and domesticity as we all move towards 2123.......

For all that Weimar sits today quietly and unassumingly between Erfurt and Jena in the green calm of Thüringen, for a great many decades it was one of the more important centres of the lands of the contemporary Germany. A position within, then, Germanic society that arguably can be traced back to its anointing in 1552 as the capital of the Duchy of Sachsen-Weimar, a status which meant that when in the late 18th century Carl August ascended to the, then, Sachsen-Weimar-Eisenach throne, initially under the regency of his mother Herzogin Anna Amalia, Weimar had over the intervening 200 years established a political and social importance and stature that enabled Carl August, and Anna Amalia, to lure the likes of Goethe, Schiller, Wieland, Herder et al to Weimar, a moment that inarguably marks the start of the rise of Weimar's cultural importance. A cultural importance that continued throughout the 19th century with the likes of, and amongst others, the composers Franz Liszt or Richard Strauss, and if by association more than physical presence, Richard Wagner, or artists such as Arnold Böcklin or Franz von Lenbach adding to the renown and relevance of the town.

A cultural and social and political importance and relevance acquired over the centuries that, arguably, was one of the primary reasons why in 1897 Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche relocated the Nietzsche-Archiv, and her terminally ill brother Friedrich, from Naumburg to Weimar, where she hoped the association of Nietzsche with Weimar, that hallowed glow that can be bestowed on one by the (hi)story of Weimar, would help allow Friedrich and his work to remain visible, relevant and accepted after his impending death. Would infer on Friedrich Nietzsche an immortality he himself had denied God.

A managed presentation and an authoring, at times literally, of Nietzsche, of the Nietzsche legacy, of the Nietzsche celebrity, cult, by Elisabeth that included a stage setting of the interior of the sibling's Weimar villa following Friedrich's death; Elisabeth arranging Friedrich's study and his bedroom, his Death Chamber, for the benefit of those who came to pay homage. And rooms, room settings, which became firm components of understandings of Friedrich Nietzsche; Friedrich Nietzsche's living and dying spaces as part of the accepted Nietzsche narrative.

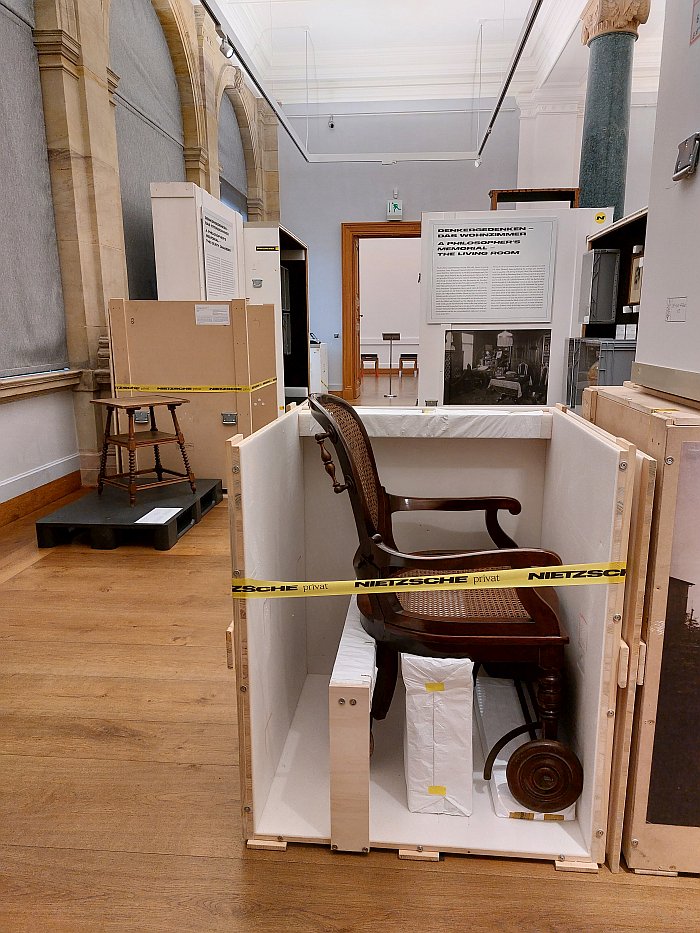

An essentially musealised staging of a Friedrich Nietzsche reality that may or may not have existed, but certainly that by 1897 Friedrich Nietzsche would have been unaware of, that is approached and discussed in the showcase Nietzsche Privat, a showcase that is our entry point for some reflections on the myriad exhibitions, installations and interventions across a dozen or so Klassik Stiftung Weimar museums and institutions, some larger scale others small, some conceptual others documentary, that compose the Wohnen - Living1 - theme year presentation.

Staged in the Neues Museum Weimar Nietzsche Privat presents unrestored furniture and objects form the Nietzsches' Weimar villa, including, for example, a lounge chair adapted to a commode which reminds that the ability to change the mode of use of a furniture object or a building over time and realities can, arguably must, be considered a component of its functionality; the finial from Friedrich's bed, all that remains of his bed, the rest, along with the majority of the props and scenery of the staged Death Chamber, having been disposed of by the DDR authorities, a reminder of Nietzsche's complex associations with the NSDAP, or perhaps more accurately given that he died in 1900, of the complexities of the Fascist veneration of Nietzsche; a wheelchair acquired for Friedrich in 1899, the year before his death, an object that is essentially a wicker backed and seated wooden framed armchair with a wheeled undercarriage and a couple of handles to aid pushing, and which despite, perhaps exactly because of, its many incongruities, and the many associations it enables, is a truly fascinating object. Or a wing back chair that Nietzsche is actually recorded as having actually used in Naumberg before he fell ill, when he was still aware of the space in which he existed and he himself chose where and how to sit and work, when his furniture was a part of his actual biography; and a wing-backed armchair whose armrests end in a clenched fist construction that reminds very much of the armrests Willy Guhl created for a late 1940s wicker shelled chair encountered in Willy Guhl. Thinking with Your Hands at the Museum für Gestaltung, Zürich, and which presented themselves as an open palm which invite you to, effectively, shake hands with the chair as you take your leave from it. Nietzsche's armrests more inviting a fist bump, which may or may not have been Nietzsche's preferred form of saying Adieu. We do hope it was.

A collection of the Nietzsches' furniture and furnishings that while they offer only little information on how the Nietzsches actually lived, actually wohnt, do allow access to differentiated perspectives on the posthumous increase of Nietzsche's fame, on the establishing of his position in European philosophy, on the biography and (hi)story that become established, accepted and repeated over time. And from there enable wider reflections on the role of furniture, and for all interior design, as mediators of information real or staged, accurate or false, directly readable or more subtle implied; that role of furniture as a mediator that, for example, an Émile Zola played so expertly with in his descriptions of the interiors of his varied and various protagonists, or which, as discussed from Living in a Box. Design and Comics at the Vitra Design Museum Schaudepot, is employed to convey information in film, tv, theatre or comics, and which today is so skilfully employed by the hospitality industry by way of conveying the flair their premises (aim to) offer (but might not), or by advertisers and estate agents to pitch their product at a particular buyer. For all in the unreflective space that is social media. Or that way we all adjust the space behind us before of a video call/conference, making sure the correct books and photos and flags are on show respective of who's going to be looking. That fact we all stage and can read the stagings of others.

Reflections on furniture as symbolic and semiotic as much as functional and formal reinforced by the very raw manner in which the objects are presented; exhibited as they are in their contemporary unrestored state, more or less as they were banished to the storerooms by the DDR authorities by way of banishing Nietzsche from (hi)story, that undoing of Elisabeth's efforts. And standing raw and unrestored in no direct relation to one another or to the space in which they stand, and thus a presentation diametrically juxtaposed to not only the care and thought with which Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche once arranged them, but to the care and thought normally afforded historic furniture in museal presentations, for all those staged, musealised, presentations of furniture in houses of historic importance and relevance, those staged, musealised, presentations of historic Wohnen that we all accept as authentic with the same ease the visitors to Friedrich Nietzsche's Death Chamber once did. Those staged, musealised, presentations we all readily accept as authentic as presented in and by the great many historic houses one can visit in Weimar.

Including Goethe's Gartenhaus, where since the early 20th century a Bock, a standing height chair, has stood in his study, where it may or many not have stood when Goethe owned the Gartenhaus.

A Bock, a Donkey, a chair "just high enough that one can sit half-standing" that, as previously noted, also appeared in the late 18th/early 19th century Journal des Luxus und der Moden - Journal of Luxury and Fashion - a clothing and interior magazine that was published in Weimar between 1786 and 1827, a publication that for us is without question one of the more interesting, fascinating, aspects of Weimar at the turn of the 18th/19th centuries, sorry Goethe, Schiller, et al; and a publication discussed in context of the Wohnen theme year in the essentially poster presentation Klassisch Konsumieren, Classical Consumption, in the Studienzentrum der Herzogin Anna Amalia Bibliothek. A presentation which although it features the May 1793 sketch of a desk with a variation of Goethe's Donkey, doesn't feature the May 1786 presentation of a chair "just high enough that one can sit half-standing", a chair, as previously postulated, potentially, possibly, designed by Goethe, and which, regardless of who authored it, and regardless if Goethe actually owned one, very much tends to imply that the standing height perch that is so contemporary today, was an invention of late 18th century Weimar. A contribution to furniture (hi)story, to relationships with furniture, those brave young things at Bauhaus Weimar seemed to have missed in their open disdain for the Weimar of yore and their striving headlong forwards; if only they'd listened a little more to the contemporaneous counsel of a P.V. Klint and thought to glance behind them as they strove into the future. And a reminder to the current brave young architecture and design students at the Bauhaus University Weimar that as P.V.'s son Kaare Klint, who very much did listen to his father's counsel, opined, in 1930 "in an aversion to everything old one loses sight of and excludes the best available help, namely to build on the experiences that have been garnered over the centuries. The problems are not so new, they have in many cases been solved before." 2

A presentation in the Studienzentrum that for all its brevity, or arguably exactly because of that brevity, is a strong admonishment to busy yourself with Journal des Luxus und der Moden, a publication that, as Klassisch Konsumieren eloquently elucidates, on the one hand was a great supporter of furniture objects which with the aid of contemporary technical invention and ingenuity could be switched between differing modes of use, not so-much Nietzsche's armchair-cum-commode and much more, for example, a so-called Study Bed presented in the April 1788 edition which could via relatively simple technology be used as a sofa or a bed, i.e. a sofa-bed; or a, if one so will, modular workstation for women presented in the January 1794 edition, which through its modularity, variability and technical cunning "alle Arbeitsbedürfnisse ihrer schönen hände befriedigt", "satisfies all the working needs of her beautiful hands", work for "beautiful hands" being understood as embroidery and sketching ... it's 1794 ¯\_(ツ)_/¯ ... Or a desk presented alongside Goethe's Donkey in the May 1786 edition which features not only a table top that can be freely tilted between flat and a 45 degree incline depending on the task at hand, but is freely height adjustable between that of a normal desk and the "height of the tallest person". Which is 'big' claim. 🙌 An early, ¿the original?, sit-to-standing height desk that can be observed, from a great distance, in the flesh in Goethe's study in his town house on Frauenplan. Where Goethe may or may not have used it. Possibly with the Donkey now staged in the Gartenhaus. Or possibly not.

And on the other hand busying yourself with Journal des Luxus und der Moden teaches us that those oh-so contemporary practices of confusing fashion for fact by way of encouraging consumption, of a generalising of discussions towards a monotony of opinion, of t*****, and of placing a value on the interiors of influencers, in context of furniture and interiors, was very much a thing in the late 18th century. A very proficiently practised thing.

The very first edition in 1786 of, then, Journal der Moden, Luxus arrived in Weimar in 1787, discussing, for example, the furniture of England with that breathless reverence and wonder that is reserved today for the furniture of Scandinavia; the August 1787 edition discussing "Zimmer-Tapezierung, im style eine bürgerlichen Ameunblemnets", "Wallpapering, in the style of a middle class ameublement" which opines "the fact that even in ordinary middle-class houses we now wallpaper our rooms is a piece of our modern luxury; but certainly a very forgivable one", which reminds very much of the Bauhaus wallpapers, those pieces of "modern luxury" that stood so incongruously juxtaposed with the 2nd Bauhaus Director Hannes Meyer's famous demand of Volksbedarf statt Luxusbedarf — The needs of people not the needs of luxury — but which as an important source of income for the school in the late 1920s was presumably "a very forgivable" contradiction. And a 1787 text on wallpaper which, before it goes on to do that contemporary thing of explaining different types of and approaches to a stylish wallpapering, the options available for the contemporary aware middle class homeowner, opines that in comparison to the expense and ostentation of a palace or stately home in context of the middle class town house wallpaper, "must be simple and inexpensive; good taste is its main characteristic and tidiness is its reward". Which takes us all back to a Verner Panton's questioning of "Why do people with so-called 'good taste' agree so much about what is good?","Isn’t 'good taste' often just boring?".3 Which, yes, you're right, does very remind of Instagram.

While the public presentation in Weimar in the autumn of 1804 of the trousseau of Maria Pawlowna, daughter of the Tsar of Russia, and new wife of Carl Friedrich, eldest son and successor of Herzog Carl August, a marriage that underscores the importance of Weimar at that period, one rarely married for love, or against paternal wishes, in 1804....... a trousseau that required some 79 wagons to transport it from St. Petersburg to Weimar is praised almost as richly and opulently as it was invariably decorated and gilded in the December 1804 and the January 1805 editions of Journal des Luxus und der Moden.

And a detailed reading of Journal des Luxus und der Moden encouraged by Klassisch Konsumieren that also tends to imply that then as now people bought furniture on the basis of what was presented in the media.

An implication supported, almost literally, by a set of chairs with upholstered seats in the Wittumspalais, the former residence of Herzogin Anna Amalia, a house in which according to the Klassik Stiftung Weimar, the "Duchess’s former parlour with its original furnishings is among the most authentic rooms in the mansion that best reflects domestic culture around 1800", a claim Wohnen leaves us all much better placed to discuss. Chairs that can also be found as three-seater sofa in Goethe's town house, albeit with woven wicker seats. And chairs in Anna Amelia's Wittumspalais which also appeared in the November 1796 edition of Journal des Luxus und der Moden in which they are praised, amongst other points, for the manner in which the feet spread beyond the seat thereby ensuring a good sitting stability, which is, in essence an expression of the Greek Klismos, thus expressive of the Greek Revival of the period, if albeit a much more reserved, understated, unobtrusive form of Klismos revivalism than was often the case. Such as for example the above noted 1786 depiction of a chair "just high enough that one can sit half-standing" that may have been authored by Goethe, or maybe not, and whose legs' exaggerated Klismos swing simply cannot work. And reserved Klismos revival chairs recommended by Journal des Luxus und der Moden for the living room which in Wittumspalais stand in the so-called Tafelrundenzimmer, a dining-cum-social-room. Or, perhaps more accurately, today stand in the Tafelrundenzimmer.

A set of 1796 chairs joined around a large table in the Tafelrundenzimmer by chairs from 1899 and 1902 designed by Richard Riemerschmid, chairs that aren't part of the Wittumspalais inventory but components of the project Fremde Freunde, an intervention in context of Wohnen which sees more contemporary objects placed in historic locations by way of instigating a dialogue. A very, very simple concept, very, very pleasingly realised, and which through juxtapositions and altered perspectives allows for some differentiated insights on not only the Wohnen of the theme year, but wider relationships with our objects of daily use. The placing, for example, of Dieter Rams' 1969 KMM 2 coffee grinder for Braun in Friedrich Schiller's kitchen, a location where 200+ years previous coffee would have been ground for Schiller, only per hand, reminding that developments in society invariably involve technical developments, that processes and practices often stay the same, but the technology changes, thus reminding us we shouldn't fear new technology, we need the new technology, but should pose hard questions of it. And also reminding that, and as discussed in context of, for example, Konstantin Grcic. New Normals at Haus am Waldsee, Berlin, or from Can You Hear It? Music and Artificial Intelligence at the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe, Hamburg, that which is today normal and familiar was once unimaginable; the objects of daily use we accept without question would appear to previous generations most odd, yet invariably arose from, are descendents of, objects they would have found normal and familiar. In addition, while viewing the KMM 2 in Schiller's kitchen we were reminded of the fact, certainly 'fact' by all contemporary accounts, that Goethe himself furnished Schiller's house, Goethe was very keen on his furniture and interiors; imagine if Goethe had bought Schiller a KMM 2 coffee grinder by way of a house warming gift. Braun and Goethe are both from Frankfurt. It's not beyond the bounds of reason. But imagine the look on the cook's face. And the fame it would have brought Schiller.

Or imagine if Goethe really had owned a fruit plate featuring artwork by El Lissitzky as displayed amongst his majolica plates in his former town house. Imagine if he really had owned a height adjustable desk and and/or a chair "just high enough that one can sit half-standing".

Or imagine if Goethe really had brought Achille & Pier Giacomo Castiglioni's 1965 RR 126 radio/record player for Brionvega back from his late 1780s travels through Italy as gift for Herzogin Anna Amelia — Brionvega are based in Milano through which Goethe passed on his way back to Weimar from Rome, Anna Amelia was very keen on her music, it could have happened — and placed it in her Tafelrundenzimmer where is stands in 2023 apparently as authentically and unquestioned as a 1946 side table by Josef Hoffmann for Jacob & Joseph Kohn or the set of Klismos revival side chairs from 1796. Or imagine if Friedrich Nietzsche really had worked at his desk as it could be viewed in the Nietzsche-Archiv after his death. Or imagine if the homes of 1930s Europe were really awash with steel tube furniture. Or imagine if your flat really did look like the one in the advertisers photos. Or imagine if our furniture and furnishings really were 3D digital visualisations like those objects of Goethe's presented in the project Goethe-Apparat in the somewhat stoutly monickered Goethe-Nationalmuseum, and not physical works as they also exist in Goethe's town house.

Or imagine if Anna Amelia really had awoken one morning to find an electric lamp by Karl Trabert for Schanzenbach & Co and a Cella S1001 typewriter by Karl Clauss Dietel for VEB Robotron on a desk in the Wittumspalais. The latter, potentially, containing a note for the Herzogin explaining that it had been produced in a future country called the Deutsche Demokratische Republik, to which Weimar belonged, but in which not only the Sachsen-Weimar-Eisenach's played no role, but were dethroned and demonised, while Goethe and Schiller were celebrated. A country where the glitz and glamour of Weimar had been dulled by a coating of disrepute on account of its role in the rise of the NSDAP, and by the presence of Nietzsche. And also, arguably, on account of its role in the rise of an institution by the name of Bauhaus, an institution that certainly in the earliest days of the DDR, and for all in context of the so-called Formalism Debate of the early 1950s, was demonised almost as much as the Sachsen-Weimar-Eisenachs. A demonisation of Bauhaus that the institution experienced live, in the flesh, in early 1920s Weimar; a rejection which, as noted and opined from Mathilde von Freytag-Loringhoven. Painter, Author, Animal Psychologist and Bauhaus Critic at the Stadtmuseum Weimar, was, at least partly, connected with a raging conflict within early 1920s Weimar between the admirers and supporters of the memory of the Weimar Klassik of Goethe, Schiller, Wieland, Herder et al on the one side and the brash, abstract, uncombed, free jazz reality of the Weimar Moderne of the brave young things at Bauhaus on the other. A conflict that neither side did particularly much to defuse, disdain flowing freely in both directions. Two diametrically juxtaposed groupings who in early 20th century Weimar arguably were only united by an appreciation of the work of Johann Sebastian Bach, an individual associated with a Weimar even older than that of Goethe et al.

A conflict in Weimar that can teach us much about the Weimar Republic, and by extrapolation the Europe of that period.

Today that conflict is as much in the past as the 1920s actually are, and Weimar's Moderne and Klassik are united within the Klassik Stiftung Weimar, even if the Stiftung's name does somewhat unfortunately imply that the Moderne element has been more taken over by than unified with the Klassik element, does somewhat clumsily tend to imply a natural primacy of Goethe, Schiller, Wieland, Herder et al over Gropius, Itten, Klee, Kandinsky et al; and thus today not only is Haus am Horn part of the Sitftung alongside the houses of the Sachsen-Weimar-Eisenach dynasty and their cohorts, but so is the new-ish Bauhaus Museum Weimar, the latter contributing to Wohnen with the project Ways to Utopia. Life Between Desire and Crisis.

A project whose title arguably could also have been coined by Walter Gropius: was Bauhaus not a component of a search for a path to a Utopia in an age of desire and crises?

As, arguably, was also the work, and age, of Goethe, Schiller, Wieland, Herder et al?

A project, an exploration of Ways to Utopia, which opens with a return to the DDR Herzogin Anna Amelia never knew via the installation Wohnmaschine 4.0 by Martin Maleschka, an architect and artist who last featured in these dispatches with his model of Eisenhüttenstadt in context of the exhibition Endless Beginning. The Transformation of the Socialist City at the Museum Utopie und Alltag, Eisenhüttenstadt, in which he joyously recreated the sickly sweet kitsch, but not unappealing or unengagingly so, of the so-called Zuckerbäckerstil, Confectionery architectural style, of Hütte in sugar cubes; and who in Weimar has arranged a wide variety of DDR era objects according to colour. Objects presented far away, almost as far away as the height adjustable, positionable desk that Goethe may or may not have used in his town house; and a lot of small things far away, and at times up so high that only "the tallest person" has unhindered access to them, that initially causes you to question the sense of the whole exercise, a question that gets even louder as lots of East Germans start reminiscing through rose-tinted telescopes of times gone by, you sense a discussion developing more on Retroptopia than Utopia. Your heart sinks. But then you're eyes become acclimatised to the distance and start focussing in on individual objects and you spot, for example, and amongst a great deal of interest, an awful lot of plastic, a reminder of that still very, very recent Utopia when synthetic plastics would make everything possible and be a great democratising force in global society, before we collectively spoilt it; copies of the DDR magazines Sozialistische Demokratie and Geschichtsunterricht und Staatsbürgerkunde, the later deliciously being the edition from October 1989, the sort of attention to detail that is always going to endear you to us, and that moment when in eastern Germany Geschichtsunterricht [History Education] and Staatsbürgerkunde [Civics] took on new contexts and functions, and acquired new narratives and content, when the Utopia of some that had the Dystopia of others suddenly offered the possibilities of new Utopias and Dystopias; or the 1953 novel Der russische Wald, The Russian Forest, by Leonid Leonow, a work written and published during the Stalinist campaign against perceived formalism and in favour of a national romantic that not only led to the aforementioned denunciation of the legacy of Bauhaus, but also led to the aforementioned Zuckerbäckerstil architecture in Hütte, that short lived Russian, and DDR, Utopia, before, as one can experience in Hütte, new Wohen Utopias were tried, and also a work of Soviet Realism that reminds of that post-War belief in technology and science as the basis of a new world, of a new global society: the atoms of an iron crystal being the very deliberate symbol of the 1958 World's Fair in Brussels. Another short lived Utopia. And a novel which in its discussion on the role, function and exploitation of forests warns of a path opening to our contemporary Dystopia. Who was listening?

And you also spot a cauliflower. Now, for our part we are very, very partial to a bit of cauliflower, but Utopia? Discuss.

And thus the more you look, and the more you identify, the more you realise the discussions being advanced and instigated, and begin yourself to reflect that Utopia isn't automatically Utopia, it's always a matter of perspective, of who defined it as a Utopia worth having, of who designed its structure, its rituals, its limits, of who decides how it progresses. And that even if all seems to be going well for the great majority, it can still all go very very badly wrong. For all if we stop paying attention. But also that Dystopias can, and do, end. That Dystopias and Utopias can and do flow freely into and out of each other.

Thoughts which very much lead you to considerations on the brave new world, the Utopia, the Bauhäusler envisaged, and from there further back to that Utopia a Friedrich Nietzsche envisaged, that Utopia a Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche sought amongst the Nueva Germania sect in Paraguay, back to those Utopias a Goethe, Schiller, Wieland, Herder et al envisaged, to that Utopia a Goethe found in his Gartenhaus on the edge of Weimar, and that Utopia the Saschen-Weimar-Eisenachs inhabited in Weimar and their in-laws the Romanovs inhabited in St. Petersburg. And even further back to a Thomas More and to the fine, but very important distinction between Utopia and Eutopia. And from there full circle to our own Utopias of the future.

And which thus sets you up for the main component(s) of Ways to Utopia: a series of interventions in the Bauhaus Museum's permanent exhibition.

A series of interventions which, amongst a great many other components, presents insights into urban planning projects in locations as diverse as for example, Wildpoldreal, Wuppertal and Weimar, a, if one so will WWW of re-imagings, repositionings, of urban spaces as components of a way towards a, the, Utopia; discusses the complex problem of the detached single family house, that popular Utopia that in an ever more densely populated world comes not only at an ever increasing economic price but at increasing social and ecological prices; considers the materials of architecture and our objects of daily use, including the greater use of recycled materials, considerations framed in context of the 1920-21 Haus Sommerfeld in Berlin by Walter Gropius and Adolf Meyer, and various Bauhaus students, that first unofficial, and so oft overlooked, Bauhaus architecture project, and a construction crafted from wood salvaged from a scrapped warship. And also asks an awful lot of questions of us visitors, including, for example, "What can long-lasting furniture tell us?", "Do we need to go to space to live well again?", or "How much kitchen does a person need?" a question which reminds that while the likes of a Margaret Lihotzsky answered such a question with a 'as little as possible through a studied optimisation of space and processes', a Mart Stam often answered such a question with a 'none', his housing estates often featuring central, communal, kitchens, a communal approach over a individual approach to food preparation and consumption reminiscent of that advanced by a Thomas More or a William Morris in their Utopias, and which poses the question whose path, whose way, to Utopia is/was better? And also takes Hannes Meyer's 1926 Co-op Interieur project as the basis for asking "What do we need for living?". Whereby we all know the answer is "a lot less than we insist on owning". Thus underscoring the important distinction between knowing what to do and doing it.

In addition Ways to Utopia very pleasingly features a section on homelessness in the form of photo projects by Simon Menner and Jana Sophia Nolle, the film What It Takes to Make a Home by Daniel Schwartz and also by presentation of statistics concerning contemporary housing realities which indicate some of the social and economic imbalances that can lead to homelessness. A presentation that while in no way as expansive, or as internationally positioned and approached, as Who’s Next? Homelessness, Architecture and Cities as seen at the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe, Hamburg, does allow access to the same sort of reflections on a contemporary reality we all know shouldn't exist, but which no-one really feels responsible for ending. See also overconsumption.

And reflections on homeless in the midsts of the furniture, furnishings and accessories of the Bauhäusler, those much celebrated advancers of positions on Wohnen, that also stands as an apposite and timeous reminder that Wohnen isn't an automatic given, sometimes the apparently so simple act of having four walls and a roof can be a Utopia, regardless of how much kitchen is there. And that having somewhere to call home, having a space for yourself, is in itself something to be treasured and protected and defended. Something to be valued above all the things you consume for that space.

And also reminds that in the early 1920s life was hard. For all the glitz and glamour of the period it was an era of wide spread slum housing and extreme poverty, and many of the Bauhäusler lived very precarious existences, were often dependent on scholarships for the fees, or on the Bauhaus leadership turning a collective blind eye to unpaid fees. And that most of the housing employed, suffered, by the Bauhaus Weimar staff and students was far removed from the Utopia of Haus am Horn.

Similarly the reflections on contemporary homelessness and precarious Wohnen as a continuation of a century old reality reminds that in the late 18th century only those who lived in the sorts of houses institutions such as Klassik Stiftung Weimar consider worthy of preserving and musealising had homes of the sort you can take an audio guide tour through today. For the greater many in late 18th century Weimar domestic life would have been pretty grim, more Existieren than Wohnen.

And today?

How did Bauhaus and their ilk impact on the path from 1823 to 2023? How did Bauhaus and their ilk alter the trajectory of domestic arrangements and domesticity? In Weimar and further afield.

As a mix of exhibitions, installations and interventions of varying scales, genres and positions in a wide variety of locations, each and every experience of Wohnen is by necessity different, individual. Is also dependent on the order in which you view the varying component parts, how much time you can afford them.

Indeed if the exhibitions are on.

When we visited Wohnen the showcase The Poet’s Household and the Art of Living had ended several weeks previously. Thus leaving us to chase up ourselves at a later date answers to questions explored in The Poet’s Household such as, for example, How did people with varying incomes live around that time? How much money did Goethe’s family spend for household goods? How and where did the domestic servants live? Or which lighting devices did Goethe use? We're guessing, without knowing, a Tolomeo Tavolo by Michele de Lucchi & Giancarlo Fassina, we'll let you know once we find out. And while we fully appreciate that in a theme year presentation that runs over several months in a variety of locations not all exhibitions can necessarily have the same opening and closing dates, that there must be variations, it surely must be possible that for at least a couple of months all are open. It's certainly an easier case to make than expecting visitors to travel to Weimar several times in a year in order to view all the showcases; we're always happy to visit Weimar, always enjoy ourselves immensely in the town, but it's got to planned into wider schemes. As does and did everybody's travel and tourism arrangements. Including Goethe's and Gropius's. And thus because we wanted to see Nietzsche Privat, we missed The Poet’s Household. It was a decision we had to make. Didn't want to, but had to. To which we'd also add that given that the next temporary exhibition in the Goethe- und Schiller-Archiv opens in mid-September closing The Poet’s Household in early July seems a little over cautious, we can't imagine the switch was going to involve that much work. But we know no.

And while we're complaining, we couldn't view the Kirms-Krakow House's contribution to Fremde Freunde, the museum only being open Friday, Saturdays and Sundays. And we being there on none of those three days. And for all that one doesn't have to see all of Wohnen to get something from it, surely the aim should be to maximise access to the presentations, to allow the possibility to view as much as possible, whether visitors take up that offer or not. And thus an appeal for better coordinated dates in coming years.

However, such didn't and doesn't detract from our viewing of or enjoyment from Wohnen, a project, a theme year, which on the one hand is a very satisfying framework via which to view and explore the properties of the Klassik Stiftung Weimar, enabling as it does a differentiated perspective on that which is on show, allowing access to differentiated questions and associations, and which tends to focus your attention more on the furniture and accessories than on the staged museumisation on which one tends to focus, thereby enabling you to spend more time with details such as, for example, and amongst other moments, the dining chairs in Goethe's town house whose backrests only reach to the top of the tabletop, the tops of the chairs and table forming a unity, a format that although not unknown today isn't that wide spread, and which also reminds of Alexander Girard's demand of Chares and Ray Eames that the backrests of dining chairs for the La Fonda del Sol restaurant in New York shouldn't reach above the tables so as not to disrupt the viewing of the space, to enable the whole spectacle to be viewed uninterrupted, which may or many not have Goethe's consideration, may or may not have been an aspect of Goethe's staging of the interior of his town house. But does aid the contemporary museumisation. And does place Goethe's chairs in a line with the Eames' La Fonda chairs, which we think would appeal to him. And which, again, brings us back to P.V. and Kaare Klint.

And on the other hand is a very nice way to view furniture not as epochs but as components of those epochs, to view and appreciate furniture not as items from an age but as consequences of the decisions the inhabitants of those ages made, of the reasons for those decisions, of the contexts in which those decisions were approached; a way of viewing furniture advanced in and encouraged by Wohnen that makes the mix of exhibitions, installations and interventions an interesting framework to consider the Weimar of ca. 1800, ca. 1900, ca. 2000, ca. 2100, to consider the differences, the similarities, the alternatives. And also to reflect on the acts of remembering the past and predicting the future as essentially similar exercises; as exercises in idealising, simplifying, romanticising, authoring, etc. Utopia building and museumisation as essentially they same practice, just in different directions.

But for all Wohnen is a very nice, and very apposite, reminder that for all that the context changes with time, understandings of and positions to domestic arrangements and domesticity are always but a reflection of how we understand the world around us, relationships between the human environment and natural environment, our place in the world and those relationships, and also a reflection of how we want to be read. Just as Haus am Horn was. And Goethe's Gartenhaus was. And your house is. And future generations' houses invariably will be.

Wohnen, or more specifically the myriad exhibitions, installations and interventions that compose Wohnen can be viewed in the properties of the Klassik Stiftung Weimar until various dates.

Full information can be found at www.klassik-stiftung.de

1Wohnen is one of those German words that it is all but impssible in one word to translate, and although used here as noun, it's probably better uderstood as a verb meaning how one lives, in all its factets not just furniture but use of space, relationships with the space, the colour scheme, the materials, the rituals and activities etc, etc, etc Thus while the official Enlish title is 'Living', because Wohnen is so much more multifacted a term, we stick with Wohnenin our text.

2Kaare Klint, Undervisningen i Møbeltegning ved Kunstakademiet, Arkitekten månedshæfte, October 1930, page 203

3Verner Panton: Meine Design-Philosophie, BÜROszene, Vol 47, Nrs. 1–2, 1995