The Swiss Design Lounge on the first floor of the Museum für Gestaltung, Zürich, is home to selected works by the good and great of 20th and 21st century Swiss furniture, lighting and textile design, including, and amongst many others, Bruno Rey, Ubald Klug, Hans Eichenberger or Susi and Ueli Berger, works which not only stand in discourse with one another but also actively invite visitors to try them out, to spend time with them, to get to know them; and while you are, and while you enjoy yourself, while your making new friends, from outside, works by Willy Guhl, thick with the lichen and moss that rolling stones don't gather, gaze through the windows on this scene of domestic harmony and mutual appreciation.

One could be forgiven for imagining that the scenography was in some way a comment on, a metaphor for, Willy Guhl's place in the (hi)story of design: outside, on the periphery, faded by the merciless passage of time.

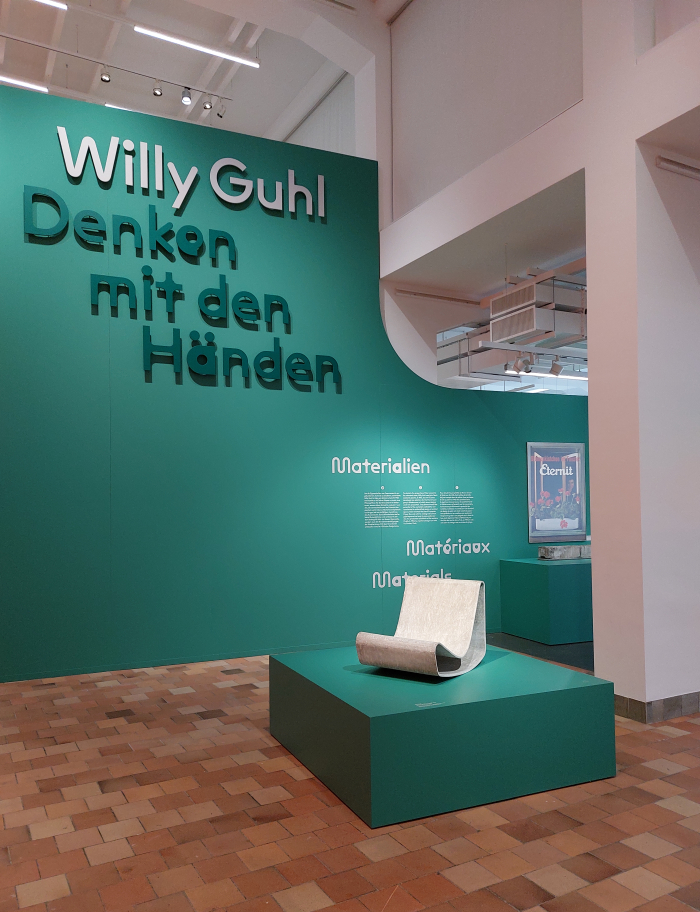

Viewing the Museum für Gestaltung, Zürich's, exhibition Willy Guhl. Thinking with Your Hands, enables a differentiated perspective, on both Willy Guhl and on the Swiss Design Lounge.......

Born on July 6th 1915 in Stein am Rhein, in northern most Switzerland, as the eldest of three children to the haberdashery store owner Marie Guhl-Singer and the Meister cabinetmaker Wilhelm Guhl, the teenage Willy Guhl initially completed an apprenticeship as a cabinetmaker, partly in his father's workshop in Stein am Rhein, partly in that of one Georg Lehle in nearby Schaffhausen, before in 1934 he enrolled in the Innenausbau, Interior Design, class at the Kunstgewerbeschule Zürich, the contemporary Zürcher Hochschule der Künste, ZHdK; a class at that time under the tutorship and influence of Wilhelm Kienzle, an architect and designer who was a very important and influential figure in helping design in Switzerland navigate its way from the 19th to the 20th century.

Following his graduation in 1938 Willy Guhl established his own draughting office in Stein am Rhein, while also sharing studio space in downtown Zürich with two former Kunstgewerbeschule colleagues, Oskar Burri and Otto Glaus: and bases in Stein am Rhein and Zürich from where Willy Guhl's career as a freelance designer begins. A start some of whose first steps can be approached and explored in Thinking with Your Hands through, for example, and amongst other works: two storage units crafted from Pavatex, a proprietary woodchip hardboard developed in Switzerland in the 1930s, and objects produced in father Guhl's solid wood orientated workshop, and which thereby represent a very nice example of a generational change in an, allegedly, unchanging craft; his 3105 chair a.k.a the Bankstuhl, a chair designed so that individual chairs can be lined up to form a bench, Willy Guhl's re-imagining, re-defining, of the traditional in-built kitchen corner seating units of Switzerland/Austria/Germany, Guhl's breaking of that immobile, unresponsive single bench into a number of independent chairs that can, if need be, unite to a bench; or a delightful multi-purpose cupboard which is, essentially, a wooden transport crate re-imagined as a cupboard. Tipped up on its end so that the door opens along a newly won vertical axis not the previous horizontal, and thereby enabling its use as a vertical cupboard rather than as a horizontal crate. And thus a very nice illustration of a Surrealist Readymade; if not actually a Readymade, being as it is a work designed to look like a transport crate rather than a reappropriated transport crate. And also a very nice take on the early 20th century box furniture of a Louise Brigham. Not that we believe Willy Guhl would have been familiar with Brigham's box furniture, although we'd be absolutely delighted if he had been and had been inspired by it, and thereby allowing for an actual, direct, influence from Brigham. Rather than the indirect verification of the validity of Brigham's positions Guhl's crate/cupboard tends to illustrate.

And early projects on show in Thinking with Your Hands that also include a family of foldable, DIY, flat-pack, furniture developed by Willy and his brother Emil1 for the 1948 Museum of Modern Art, MoMA, New York's International Competition for Low-Cost Furniture, that competition that was so influential and important in advancing 20th century design positions in the immediate post-War decades. Intended to be realised, as best we can ascertain, in a mix of solid wood and plywood, the key, the defining principle, the core, of the project is and was what are referred to as linen hinges: strips of sturdy linen integrated into lengths of plywood which allow the plywood to be folded at pre-defined sections into a stable quadratic form,2 and subsequently attached to a solid wood frame to create the required furniture object. A project presented in Thinking with Your Hands by plans, photos, and a small table, which allow one to follow the very simple concept; a project which through the use of the linen hinges allows for the use of much thinner sheets of plywood than would be possible if one was joining the plywood with metal hinges and screws, and thus not only enables reduced plywood usage, and thus the lower-cost of the competition title, but also enables a much simpler construction process for the end user, one simply folds the wood as if it were cardboard; a project that neither won an award in the MoMA competition nor ever entered production, but is no less interesting and informative for that fact.

And foldable flat-pack furniture, and Pavatex furniture and a Readymade transport crate, that are all very succinct and engaging examples of, positions to, the enabling of low-cost, practical, durable, meaningful furniture, a subject that was both contemporary and urgent in the late 1940s against not only the background of the material shortages of the period but also the need amongst a great many throughout Europe to quickly and cheaply re-furnish after the destructive brutality of the War and in context of the associated economic uncertainty. And, and importantly, are also very neat examples of finding solutions for providing furniture that go beyond individual furniture items, and instead consider novel furniture systems, consider novel approaches to, novel processes of, furniture construction and provision that offer the possibility for further expansion and development at a later date. As ever, furniture design is as much about designing systems and methodologies and relationships as it is about designing chairs. Even if that is all to easily forgotten in our contemporary world of instantaneous visual consumption.

While the MoMA (largely) overlooked the Guhls' folding flat-pack furniture - the project was presented in the subsequent MoMA exhibition but otherwise went unrecognised - a further project submitted to the competition was recognised; not with a prize but with inclusion, a highlighting, in the subsequent exhibition catalogue. A second project that helps further elucidate Willy Guhl as a designer searching for novel solutions, novel relationships, valid and appropriate for the contemporary age; a designer very much aware of the relevance and urgency of the contemporary contexts and realities in which he is working.

Or as Willy Guhl wrote in 1950, "our age demands differentiated chair forms that correspond to the differentiated forms of sitting",3 a truism of all ages, if one that, again, is regularly overlooked, not least when profit rears its bloated head; and an appreciation the Guhls' approached through a series of experimental investigations of seating and sitting. A series of practical seating studies they submitted to the MoMA competition, and from which the judges highlighted a recliner/chaise longue, a work that in the subsequent exhibtion catalogue stood directly juxtaposed with, and was favourably compared to, what would become the La Chaise lounger by Charles and Ray Eames, the MoMA noting that the Eames' project and the Guhls' represented "an interesting example of parallel thinking on both sides of the Atlantic"4, and, arguably, there would have been no way one side could have known about the other's project, each worked without knowledge of the other; yet there are unmistakable similarities, if also a great many differences, between the two. Between the projects, and also, we'd argue, between Willy Guhl and Charles and Ray Eames.

An experimental moulded recliner/chaise longue by Willy and Emil Guhl which can be considered a visualisation of Guhl's position that reclining represents "the last sitting phase", and one in which "the body is completely relaxed"5, or at least should be and thus requires appropriate support; an experimental moulded recliner that embodies Guhl's demand that for a comfortable lounger/recliner the focus of the designer should be on a "well differentiated forming of the backrest and headrest, armrests and support for the back of the knees"6; an experimental moulded recliner that although it never got beyond models and prototypes has found unmistakable formal and conceptual echoes in numerous recliners and loungers since. And an experimental moulded recliner which although from the 1940s, doesn't speak to you of the 1940s, indeed openly denies that it was around in the 1940s, and instead talks very much, and very animatedly, and very proficiently, of 1960s and 1970s moulded plastic. A looking forward, a prediction of an age to come, found in a great many works by Willy Guhl

While a further result of the Guhls' late-1940s seating studies does more than just talk of 1960s and 1970s moulded plastic. Does more than just look forward and predict.

From relatively early in his career Willy Guhl was an ardent and adventurous explorer and champion and challenger of novel materials, something that can, in many regards, be understood in his use, his early adoption of, his experimentation with, Pavatex as an alternative to virgin wood in furniture.

And a passion and interest for and in materials, for all novel materials, gloriously, deliciously, underscored, celebrated, in a seat shell crafted by Willy and Emil Guhl in 1951 from Scobalit, a fibreglass based material developed in Switzerland in 1950 and which initially found, and still finds, use in and for, for example, skylights, balcony cladding, shed roofing, partition walls, greenhouse roofing, etc, etc, etc. A seat shell developed in context of the Guhls' late-1940s seating studies, but which couldn't be realised until 1950, couldn't exist until a suitable synthetic plastic existed, and thus can be considered, if so one will, a theoretical, conceptual, project prepared for a coming physical and material reality; a seat shell that features an ingeniously, unobtrusively, subtly, in-built handle to aid carrying it; a seat shell which with its short backrest and extended seat cuts a very singular, but not unattractive, not unappealing, figure; a seat shell which with its short backrest can be understood as representative of Willy Guhl's position that "one must be able to move on a chair"7, that forcing, enforcing, a single specific static sitting position was one of the problems with chairs, and with no backrest above the small of the back, one is much freer; a seat shell which with its short backrest tends to echo Marcel Breuer's 1925 opinion that one of the primary requirements for comfortable sitting is and was "freedom of the spine because each and very pressure on the spine is both uncomfortable and unhealthy"8, and with no backrest above the small of the back, one's spine is much freer; a seat shell which with its short backrest requires less material than one with a full length backrest; a seat shell which is a shear joy to engage with. And a seat shell which bears an uncanny conceptual relation to the 1953/54 prototype for a moulded, folded, casually squashed, chair by Poul Kjærholm that featured in Mimesis. A Living Design at the Centre Pompidou-Metz, a work by Kjærholm that is also characterised by an unusually short backrest and extended seat, and the resultant singular, but not unattractive, not unappealing, figure; Kjærholm's was however in pressed aluminium and not moulded in fibreglass.

And a moulded Scobalit shell the Museum für Gestaltung claim was the first moulded plastic seat shell in Europe, and which, we'll claim, may very well have been the first moulded plastic side chair shell anywhere: while the Eames fibreglass A shell with its armrests was released in 1950, it was 1953 before the fibreglass S shell, their side chair shell, was formally launched, after the Eames's had solved their production problems. Just sayin'.

A work, a seat shell, from a material more normally used for roofing that, in many regards, pre-empts, predicts, finds an echo decades later, in the Postmodernists use of, appropriation, of materials.

And a seat shell from a material more normally used for roofing that also pre-empts, and predicts, that project for which Willy Guhl is unquestionably most popularly known: his cooperation from ca. 1951 with Eternit, manufacturer of an eponymously monickered fibre cement, a material primarily employed for making pre-fabricated roofing sections, and from which Guhl crafted a collection of garden and balcony accessories and furniture including, for example, a container for a child's sandpit, window/balcony flower boxes, the so-called Elefantenohr, Elephant Ear, a free-formed object whose use is equally liberated and undefined. And, and inarguably most famously, the chair Loop, an organically flowing, curving, sweeping, band of Eternit whose visual lightness belies its structural and physical stability.

In addition to his cooperation with Eternit the 1950s also saw Guhl begin varied and various commercial cooperations including with, for example, and as can be seen in Thinking with Your Hands, Aweso, a shop-fitting contractor whose metal wall units he re-worked to develop a modular bookshelf/shelving system, for home and office, which required no drilling into floors or walls to ensure stability, to which we say Hurrah!!!; with the Dietiker furniture company in his native Stein am Rhein, who not only took up production of the Bankstuhl but incorporated the Bankstuhl into a Guhl Collection of upholstered and unupholstered chairs based around his new 3100 chair, and who also began industrially producing Guhl's wooden furniture as opposed to the previous craft processes; or with the Institute of Balneology at the Technische Universität München with whom Guhl developed a bath tub, the so-called circulatory tub, intended to be more responsive to the physical, and medical, needs of cardiovascular patients, and which were installed in the spa at Bad Wiessee on the banks of the Tegnersee in southern Bavaria.

In addition, and as one can read in the catalogue raisonné within the Thinking with Your Hands catalogue, the 1950s also saw Guhl develop innumerable private furniture and interior design commissions, including a sofa, chair and side table for Johannes Itten, which sounds like an improbable combination, Guhl and Itten, ¿¡¿¡¿Guhl and Itten?!?!?"9.... but we digress........; and thus the 1950s, one can argue, marks that decade in which Willy Guhl become a firmly established element of the furniture and design industry in Switzerland.

Before in the 1960s things got a little quieter, a lot quieter; in Thinking with Your Hands you will struggle to find published works designed by Willy Guhl after about 1961.

Why?

??

???

Unless we missed it, which is always possible, we miss a lot, the why the lack of objects after 1961 isn't a question that Thinking with Your Hands approaches; and in any case, we suspect that there would be no simple answer, or at least not one that can be accurately told any more.

But what was, potentially, a contributing factor, and a subject very much approached in Thinking with Your Hands, is and was Willy Guhl's increasing engagement with his alma mater, the Kunstgewerbeschule Zürich, from 1951 onwards.

Willy Guhl's career in teaching is almost as long as that as a published designer: his first teaching engagement coming in 1941 when took up a post as a part-time tutor at the Kunstgewerbeschule, and also began teaching apprentice carpenters at the Gewerbeschule Zürich, and thus was employed simultaneously with a not irrelevant mix of traditional craft and contemporary design, before in 1951 he was appointed head of the Innenausbau class at the Kunstgewerbeschule, and that as the direct successor of Wilhelm Kienzle; a class that in 1965 he repositioned as Innenarchitektur und Produktgestaltung, Interior Architecture/Design and Product Design and thus decisively, fundamentally, expanded the fields in which Kunstgewerbeschule graduates were trained.

A career as a design educator explored in Thinking with Your Hands less through Willy Guhl, as through his students, through the work of his students; through a presentation of study models and realised products, by the likes of, and amongst many others, Bruno Rey, Ubald Klug, Ludwig Walser, Trix and Robert Haussmann, Klaus Vogt, or Reni Shulman-Trüdinger, the latter of whom is represented by her 1956 Type 2 sideboard system, an endlessly extendable metal and wood sideboard system that could be released tomorrow and still give the impression of being ahead of its time in terms of material responsibility, functionality and its relationships with the user.

And a discussion on Willy Guhl's career as a design educator as explained through the work of his students which is a very pleasing and very satisfying decision by the curators, not least as it allows for an interesting and informative expansion of appreciations of Guhl's relevance based on his direct and indirect influence rather than on that which he did, appreciations based on how he taught, what his pupils took from that teaching, how his pupils interpreted his teaching in their age.

And as such allows for interesting and informative and expanded reflections on Willy Guhl's place on the helix of design (hi)story.

Although works by Willy Guhl after 1961 are rare in Thinking with Your Hands they are not non-existent, amongst those on show one can revel in, for example, a 1962 glass and metal side table for Perk Metallwarenfabrik, or the so-called Uristier, Ox Head, chair for Dietiker, or two 1997 flat-pack metal candleholders which one slots together and then slots apart to store unobtrusively, and candleholders that are not only a delight in themselves, but succinct encapsulations of many aspects of Guhl's work and approach. And you can also revel in, and sit in, a Terratrac TT 33 for Aebi & Co., a small multi-purpose agricultural vehicle specialised for steep slopes, of which Switzerland has a great many, and one of the singular highlights of Thinking with Your Hands: less for being a small multi-purpose agricultural vehicle, or because you are actively encouraged to sit in it, but more on account of the way it helps expand appreciations of Willy Guhl and his work further than you could have reasonably expected.

Beyond the works on show in Thinking with Your Hands the accompanying catalogue lists and illustrates a host of further post-1961 projects; projects both undertaken by Guhl himself and also, and again very pleasingly and very satisfyingly, a great many projects undertaking by his students, including, and amongst many others, a 1962 seminar which challenged the students to develop handles for the brushes of the manufacturer Just, or a 1974 project with Dr Best toothbrushes, and thus the sort of real life projects that are so important in contemporary design education; or a 1976 project in cooperation with the League of Red Cross Societies to develop objects to aid and abet disaster relief responses, and the sort of project that helps students think in new ways about familiar objects, while also reminding them that design is, should be, about more than commercial objects and gains; and also a 1962 project to develop furniture that could be produced using the equipment in the Gewerbeschule Zürich's carpentry workshop, a linking of design and craft, that, as already opined, is not irrelevant in the biography of Willy Guhl, and a project which realised a couple of works to which we will return another day.

A further post-1961 project not directly on show in Thinking with Your Hands, however we believe is present in one of the videos that runs on constant loop and which provide extra depth to the presentation, but a post-1961 project certainly most relevant to the Willy Guhl biography, is his renovation and interior design of a house in Hemishofen, a small Swiss enclave within Germany, on the northern bank of the Rhein, more or less directly across the river from Stein am Rhein, that Willy and his wife Hilde purchased in 1975 and where they set up home following Willy's retiral from the Kunstgewerbeschule in 1980.

A retiral more in name than practice; post-1980 Willy Guhl continued to develop furniture and interior design projects, including participating in, leading, the renovation and refurnishing of the protestant church in Stein am Rhein, a project for which Guhl, together with Dietiker, developed pews which could be removed to create more floor space if required, and pews in which, and most importantly, as Adalbert Locher noted, "the subtlety is hidden: in a few simple steps the front rows of pews can be, stored, nested, within one another ... the old master [has] designed a stacking chair"10, technically a stacking pew, a horizontal stacking pew, a previously unknown genre, but one which fits very well in Willy Guhl's long career of re-imagining the existing. As does his insistence on the use of simple church furniture crafted from oak and fir, rather than the heavy, dark representative furniture of yore and so admired by officers of the church. And retiral years in Hemishofen that also saw Guhl develop a lamp for Glas Trösch, a lamp that was, ostensibly, little more than a vertical piece of industrial glass, a lamp that was an awful lot more than just a vertical piece of industrial glass, a lamp launched in 2002. And a lamp that represents Willy Guhl's last published design.

Willy Guhl died in Hemishofen on October 4th 2004, aged just 89.

Built around ten succinct thematic chapters, Thinking with Your Hands features, alongside examples of Willy Guhl's furniture design, his students' designs or his experimentations with materials and forms, brief discussions on, for example, Willy Guhl the collector, a collector of forms and solutions and colours and curiosities. A collector of things others miss or ignore but which delight the designer. A collector as are and were so many furniture and product designers, past and present, including, as we all remember from the exhibition Mon univers, Le Corbusier, to remain in a Swiss context, if with a designer of a very different type, and with a very different relationship to Zürich.

And also features examples of Guhl's toy design work, works that are, and generalising a little irresponsibly, largely about tactility, mental agility, hand eye coordination, spatial conception. A canon of work featuring lots of variations on building block sets; toys which, as one can observe, Guhl regularly designed so that they were their own packaging, much as his transport crate cupboard could also be used as an actual transport crate if required, and a further lovely lesson from Willy Guhl on resource responsibility. And toys, or at least some of which, visitors old and young are encouraged to play with, to construct and invent and puzzle, while the table next door features various constellations of ropes which visitors are encouraged to knot and braid and weave and tie and etc, etc, etc. And thus two tables of the thinking with your hands of the exhibtion title, and thinking with your hands inherent in Willy Guhl's approach to his design; of design through modelling and touching and experiencing, of objects as something one interacts with in a myriad ways and which therefore must be designed in context of use and interaction, of Willy Guhl's position that objects are "seen" with the hands, and, so the argument, must therefore be formed by the hands, not by the eyes.11

Willy Guhl's approach to design, one learns, was very much hands on. And whole body on if necessary; as can be understood in the late-1940s seating studies in which the three idealised chair forms the Guhls developed are derived from the accumulated imprints of numerous test sitters in clay, numerous tests sitters, who has Guhl notes, sat for long periods and who thus left behind impressions of the various positions they took and their movement while sitting, rather than a, less meaningful, single momentary snapshot of their sitting.12 Or their reclining in context of the recliner/chaise longue, that embodiment of "the last sitting phase", highlighted by MoMA.

A recliner that, again unless we missed it, isn't physically present in Thinking with Your Hands; is very much there in sketches and photos and theories, but, sadly, not in person. And while that is invariably because a physical recliner doesn't exist, the absence of a recreation does feel like an avoidable omission.

Loop, in contrast, is very pleasingly nearly absent. It greets you at the entrance, but then vanishes into the background and leaves the rest of Guhl's oeuvre to guide you through the narrative.

A narrative populated by works which for all their tactility and manually derived forms, and for all their considerations on resources and materials and usability, also regularly feature very playful details, details which one suspects come from a playfulness of character on the part of Guhl; playful details such as the aforementioned handle on the Scobalit chair, utterly unnecessary, but a joy as a nice bit thinking out loud on the question of how a designer can aid the carrying of a chair and an extra, organic, contour that disrupts the otherwise rational silhouette. Or a metal foot form Guhl was obviously very, very fond of in the 1950s and which gives the impression the foot has been fixed askew, the leg not coming down into the middle of the footplate, but sitting slightly off-centre, thereby bequeathing the whole the impression of being an actual foot of an actual animal. Possibly as a play on the carved paws and claws and similar animal feet on which chairs once stood. But which until you realise is a thing, very much resembles an awful mistake. And which, we'll argue, is once again an example of Willy Guhl channelling the inter-War Surrealists and also pre-empting, predicting, the coming Postmodernists and their frivolity and irreverence and criticisms and expanded definition of function.

A narrative populated by works which although they should very much be considered as a whole and in context of each other; one is very much invited to get up close and personal with individually. Alongside the aforementioned Scobalit chair, transport crate cupboard and foldable flat-pack furniture, for our part we were very take with, for example, a 1948 prototype for a metal wire garden chair, a work known as the Spider chair, but which is very clearly a Spider's Web chair; an unapologetically chunky 1971 folding plywood chair by Trix and Robert Haussmann for Dietiker which features a small outgrowth to enable a very simple joining of chairs to fixed rows, but which strikes us as also being perfect for hanging a bag/hat on, or bashing your hip against in a moment of inattention; and a wicker shelled chair developed in context of the late-1940s seating studies research, a work whose great many joys include its large, rustic armrests that could double as side tables. And armrests whose ends present themselves in a very singular profile which allows one to grasp them as if shaking hands and thus offers more stability when getting up; and a form, a profile, which the catalogue informs us Guhl claimed to have "designed blindfolded with a file and sandpaper".13 Which is extreme thinking with your hands. If true.

A narrative populated by works which have lost nothing in contemporaneousness or joy or elegance or communicative faculties over the decades since their genesis, and that, we'd argue, not least because they were designed not as objects, but as responses to specific questions, problems, inefficiencies and realities, represent a designer's honest approach to specific questions, problems, inefficiencies and realities, not a designers attempt to design a chair, table, toy, terratrac, recliner, whatever.

And works not represented in the Museum für Gestaltung's Swiss Design Lounge.

¿And works not represented in the Museum für Gestaltung's Swiss Design Lounge?

There is mention made in the Thinking with Your Hands catalogue of an apparent habit of Willy Guhl's to plant radish seeds in peoples' window boxes as he walked to work, by way of encouraging more self-production of healthy food in Zürich; an absolutely joyous, and very early, example of Guerilla Gardening, a habit which tends to underscore the playfulness of character we supposed above, and also a habit which has something of a man who wants to indicate that alternatives are possible, and easily achievable, and in his opinion desirable, but who doesn't get all preachy on you, doesn't force his position upon you, doesn't post a pamphlet in your postbox; rather indicates what he would do, and leaves you to decide what you want to do, leaves you to come in your own time and your own way, to your own conclusions and responses to his proposition in context of prevailing realities.

As an exhibition Thinking with Your Hands tends to underscore such an appreciation, and in doing so tends to underscore an understanding that with his work as a designer and as an educator, Willy Guhl planted radish seeds in 20th century Swiss design, planted his thoughts on materials, functionality, usability, relationships, formal expressions, project development, etc, etc, etc, but left it to others to decide what to do with them, to come to their own conclusions and responses in context of contemporary realities as they experienced them.

Conclusions and responses that populate the Swiss Design Lounge in the Museum für Gestaltung; conclusions and responses that pullulate, sprout forth, bloom within the Swiss Design Lounge in the Museum für Gestaltung.

Or put another way; the scenography of the Swiss Design Lounge in the Museum für Gestaltung can very much be understood as a metaphor. Just not the one you thought it was before viewing Thinking with Your Hands.

While Willy Guhl is definitely outside the Swiss Design Lounge14, on returning from Thinking with Your Hands you understand that he isn't gazing forlornly on a world that has no place for him; rather, Willy Guhl is observing from afar.

Observing as a teacher watching his students from a distance, seeing their mistakes, seeing their successes, but never intervening nor claiming any part for himself, rather simply observing with that quiet satisfaction of watching one's former charges make their own way forward, on their own terms and with their own positions, that quiet satisfaction of watching them take his place, watching them influence and inform as he once did. And letting them get on with it.

In addition to a direct influence on, for example, a Klaus Vogt, a Bruno Rey, or an Ubald Klug who all studied under Willy Guhl, the Swiss Design Lounge also features more indirect associations including, for example, amongst others, the shelving unit Pile by Moritz Schmid for Glas Trösch, a shelving unit that owes more than a nod of gratitude to the aforementioned 1956 Type 2 sideboard system by Reni Shulman-Trüdinger, and a work produced for that company for whom Guhl created his last published work, a work by Guhl commissioned in context of Glas Trösch's entry into the furniture and lighting market, and commissioned under the direction of the, then, in-house designer, Martin Zbären, a former Guhl student. And thus Willy Guhl can be considered as indirectly responsible for Glas Trösch's place in the Swiss Design Lounge. Similarly Dietiker, who Willy Guhl not only helped establish themselves in the Swiss design furniture market in the 1950s and 60s, but who subsequently commissioned several of Guhl's pupils, most famously, and most commercially successfully, Bruno Rey. Or Röthlisberger Kollektion, who currently don't have any Willy Guhl in their portfolio, but not only have in a Koni Ochsner, Stefan Zwicky, Ubald Klug or Trix & Robert Haussmann a goodly number Guhl students in their portfolio, but a Willy Guhl who is omnipresent in what they do, where would a Röthlisberger Kollektion be today without the influence of Willy Guhl? Where would furniture design in Switzerland be today without Willy Guhl? Where would furniture design in Switzerland be without the contribution of Willy Guhl both directly through his own works and indirectly through the influence of his students on not only coming generations of designers, but coming generations of users and consumers? Without Willy Guhl's influence on understandings of and positions to the objects with which we surround ourselves?

We're not saying that without Willy Guhl there would be no furniture and product design in 21st century Switzerland, that would be going waaaaaaaaaay too far, even for us and our singular hang to hyperbole, and even if we were to claim such, the briefest of tours through the Swiss Design Lounge with its works by, for example, Susi & Ueli Berger or Hans Eichenberger or Le Corbusier, would soon destroy our claim and reveal us for the charlatans we are; but, we are saying, and as Thinking with Your Hands allows one to appreciate, that in his positions to and understandings of design, in his interpretation of the role and function of a designer, in his understandings of relationships between object and use, between object and user, in his interest in the possibilities of novel material, in his sensitive, responsible, material usage, in his definition of function, in his easy transfer between craft and industrial processes and approaches, and in his respectful yet critical relationship with the objects and rituals of ages past, and in the undogmatic, open, playful, unpretentious manner in which he mediated that to his students, and through his published design to consumers, Willy Guhl made a fundamentally important contribution to keeping design in Switzerland contemporary, keeping design in Switzerland focussed on contemporary Switzerland, contemporary Europe, and helped design in Switzerland avoid becoming, avoid the risk of becoming, the clichéd pastiche that is Swiss cheese. Are saying that without Willy Guhl the Swiss Design Lounge in the Museum für Gestaltung, Zürich, would be a very, very different place. A place with a very different understanding of itself. And a lot less interesting and responsive and communicative. You wouldn't make as many friends. You wouldn't have as much fun.

A readily accessible and intelligently designed exhibtion whose various and varied objects are supported by innumerable photos, sketches, prototypes and models, by video interviews with some of Guhl's former students and also by concise, comprehensible, trilingual German/French/English texts, Thinking with Your Hands helps place Willy Guhl as a designer who developed and honed his craft and positions in an era which was an important and informative period in the (hi)story of design, in the development of design as a profession. And a period he clearly understood and responded to. But very much in his own way. The 1950s, for example, that period in which Guhl was establishing himself, is today intimately related to gute Form as practised and propagated by, for example, a Max Bill, who is featured in the Swiss Design Lounge; and while Willy Guhl's work is unquestionably gut, at times sehr gut, occasionally even außerordentlich gut, it is devoid of the programmatic and ideological of that which Bill and his ilk were doing. Similarly while one can, without question, find references to and links with inter-War Modernism as practised by, and to remain in a Swiss context, a Le Corbusier, represented in the Swiss Design Lounge, or a Hannes Meyer, not, it isn't applied so directly as by, for example, a Fritz Haller, whose modular storage system for USM is also very present in the Swiss Design Lounge. Rather in his works and approaches and positions one can see Guhl questioning many of the tenets of the inter-War years, while not rejecting them outright, much as, for example, one finds in the works and approaches and positions of, for example, Alvar and Aino Aalto or the aforementioned Charles and Ray Eames or a Karl Clauss Dietel. And a questioning, a playful questioning, and a very early prediction of Postmodernism, that can be appreciated in many of 1960s and 1970s and 1980s works by his students.

Is an exhibtion that allows easy access to appreciations of Willy Guhl as a multi-dimensional creative, a designer who was simultaneously a traditional craftsman, a Postmodernist questioner and challenger, and a functionalist, just not of the dogmatic form follows function type, but more of the emotional, tactile, responsive, form follows hands type. Appreciations of Willy Guhl as a designer who sought contemporary responses to contemporary questions through evolution not revolution, was very much focussed on disrupting the existing, re-working and re-positioning the existing in a new age. A designer who very much has that focus on materials, on using the specific qualities of material, of working with a material, that is the dominion of the crafter, but did so as a designer. A designer who was very much not only an explorer of the possibilities of new materials, but aware of the necessity of using materials respectfully and using as little as possible. A designer who was very much aware of his works in wider contexts, was aware of his works having numerous roles and having numerous functionalities, a designer aware of his responsibilities as being more than commercial or artistic. A designer who did his thing.

Is an exhibition that highlights, reinforces, the importance of the interplay between Guhl and his students, and the importance of that exchange to the ongoing development of design in Switzerland, much as the interplay between Wilhelm Kienzle and his students, not least Willy Guhl, in its time was important for the development of design in Switzerland. Similarly, the interplay between a Kaare Klint and his students which was important for the development of design in Denmark, or the interplay between an Eliel Saarinen and his students which was important for the development of design in America, or the interplay between a Hans Gugelot and his students which was important for the development of design in Germany West, or the interplay between a Christa Petroff-Bohne and her students which was important for the development of design in Germany East. Or put another way, as an exhibition Thinking with Your Hands reminds us all that you can overlook and dismiss design educators and design schools when considering the (hi)story of design and concentrate on the realised products of selected creatives, but you do so at your peril.

And an exhibition that having viewed and returned to Swiss Design Lounge, allows one to appreciate not only the field of radishes that now stands before you, but that the lichen and moss that cloaks Willy Guhl's works that gaze through the windows is but the patina that time bequeaths all that is intended to withstand the passage of time; is the confirmation that the Eternit objects you're viewing are from a particular time and place in (hi)story, that they've been around a long time, a time which has seen changes everywhere and in all contexts, and while the objects can and should, definitely should, be enjoyed today, what is important is less the physical objects, which can become thick with lichen and moss, and much more what they represent, the whats, whys and wherefores. The whats, whys and wherefores of Willy Guhl, the legacy and relevance of Willy Guhl that is contained and inherent in those works. The what a Willy Guhl can contribute to contemporary design, to contemporary discourses around and on design. And that, as Thinking with Your Hands elegantly elucidates, is something that time can never fade and diminish, can never become overgrown with lichen and moss. But we can lose sight of it.......

Willy Guhl. Thinking with Your Hands is scheduled to run at the Museum für Gestaltung, Ausstellungsstrasse 60, 8005 Zürich until Sunday March 26th.

Full information, including information on opening times, ticket prices, current hygiene rules, and details of the accompanying fringe programme can be found at https://museum-gestaltung.ch/willy-guhl

A richly illustrated catalogue featuring numerous essays a comprehensive catalogue raisonné is available in German and English through Lars Müller Publishers.

1Although Emil Guhl is very present in the early stages of Willy Guhl we can find no biographical data on him, also the catalogue, unless we missed it has nothing. He may later have run a restaurant in Stein am Rhein, but we can't be certain. But would argue his part of the (hi)story is not irrelevant and thus needs to be popularly more accessible.......

2See the nattily tile Swiss Patent CH272645A, Bauelement mit einer Platte, an welcher Platten angelenkt sind, die quer zur Ebene der erstgennanten Platte einstellbar sind. Published 16.03.1951 Available via https://worldwide.espacenet.com/publicationDetails/originalDocument?CC=CH&NR=272645A&KC=A&FT=D&ND=3&date=19501231&DB=EPODOC&locale=en_EP# (accessed 15.12.2022)

3Willy Guhl, Studien über Sitzformen, Bauen+Wohnen, Nr. 8, 1950 25-29 Available via https://www.e-periodica.ch/digbib/view?pid=buw-001%3A1947%3A1%3A%3A823&referrer=search#823 (accessed 15.12.2022)

4Edgar Kaufmann, Jr, Prize Designs for Modern Furniture, Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1950 page 58-59 See also MoMA press release "Prize-winning furniture in the International Low-Cost Furniture Design Competition to go on exhibition at the museum", May 1st 1950 Both available via https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/1795 ((accessed 15.12.2022)

5Willy Guhl, Studien über Sitzformen, Bauen+Wohnen, Nr. 8, 1950 25-29 Available via https://www.e-periodica.ch/digbib/view?pid=buw-001%3A1947%3A1%3A%3A823&referrer=search#823 (accessed 15.12.2022)

6ibid.

7ibid.

8Marcel Breuer, "Die Möbelabteilung des Staatlichen Bauhauses zu Weimar", Fachblatt für Holzarbeiter, Berlin, Januar 1925

9Guhl also designed the interior of a house in Hochrüti for Itten, see Museum für Gestaltung, Renate Menzi [Eds.], Thinking with Your Hands, Lars Müller Publishers, Zürich, 2023 page 271 For all the apparent contradictions between Itten and Guhl, one must remember that Itten was director of the Kunstgewerbeschule when Guhl began teaching there and also when Guhl was promoted to head of the Innenausbau class, and, presumably, Itten was responsible for both decisions. And so the two knew each other and presumably got on well with one another. But still an odd couple.

10Adalbert Locher, Stilstreit in Stein a. R., Hochparterre: Zeitschrift für Architektur und Design, Vol 8, Nr. 6-7, 1995 Available via https://www.e-periodica.ch/digbib/view?pid=hoc-001%3A1995%3A8%3A%3A265#265 (accessed 15.12.2022)

11Willy Guhl, Studien über Sitzformen, Bauen+Wohnen, Nr. 8, 1950 25-29 Available via https://www.e-periodica.ch/digbib/view?pid=buw-001%3A1947%3A1%3A%3A823&referrer=search#823 (accessed 15.12.2022)

12see ibid

13Museum für Gestaltung, Renate Menzi [Eds.], Thinking with Your Hands, Lars Müller Publishers, Zürich, 2023, page 109

14Whereby it is also important to add (a) the works by Guhl are for Eternit, and so while thyy can be used inside, are very much intended for outdoor, so standing outside they are in their natural environment, and (b) if we understand correctly all the works in the Swiss Design Lounge are currently in production, and if we also understand correctly, essentially nothing by Willy Guhl is, save a couple of items through Eternit, and so there is nothing from Willy Guhl to show. A fact, if it is one, and which we believe it is, which is a truly shocking indictment of how Willy Guhl and his work are understood and appreciated today. And also is highly instructive of the dangers of the popular telling of the (hi)story of furniture design through consumable objects; for, and without taking anything away from the designers and the works on show, the designers and works produced today, if that of a Willy Guhl, isn't, how well can we really ever appreciate the complexities of the (hi)story of furniture design?