Design Calendar | Designer | Knoll | Producer | Vitra

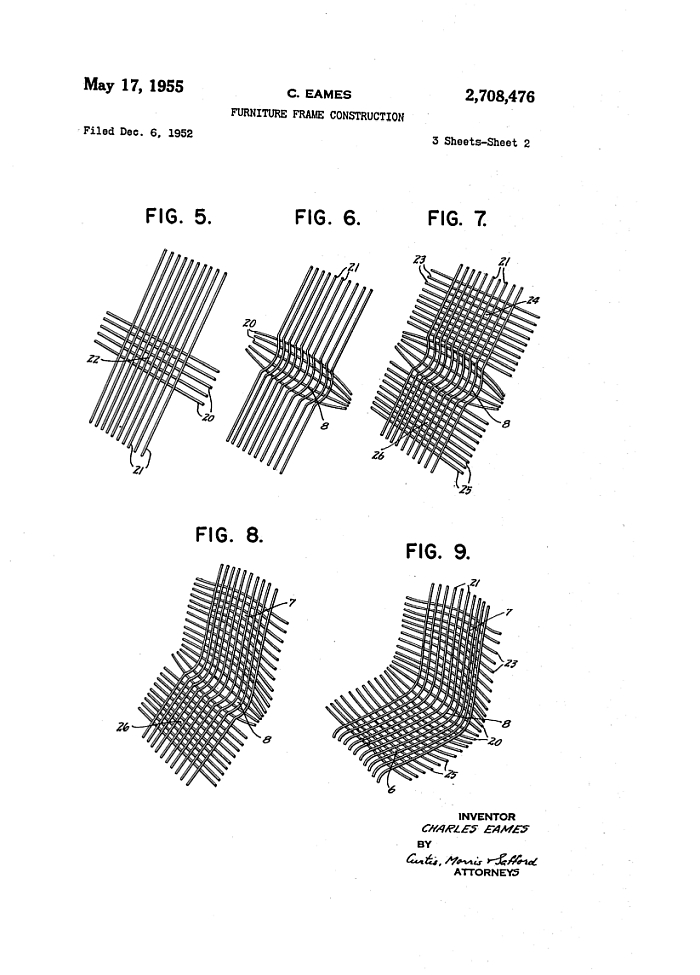

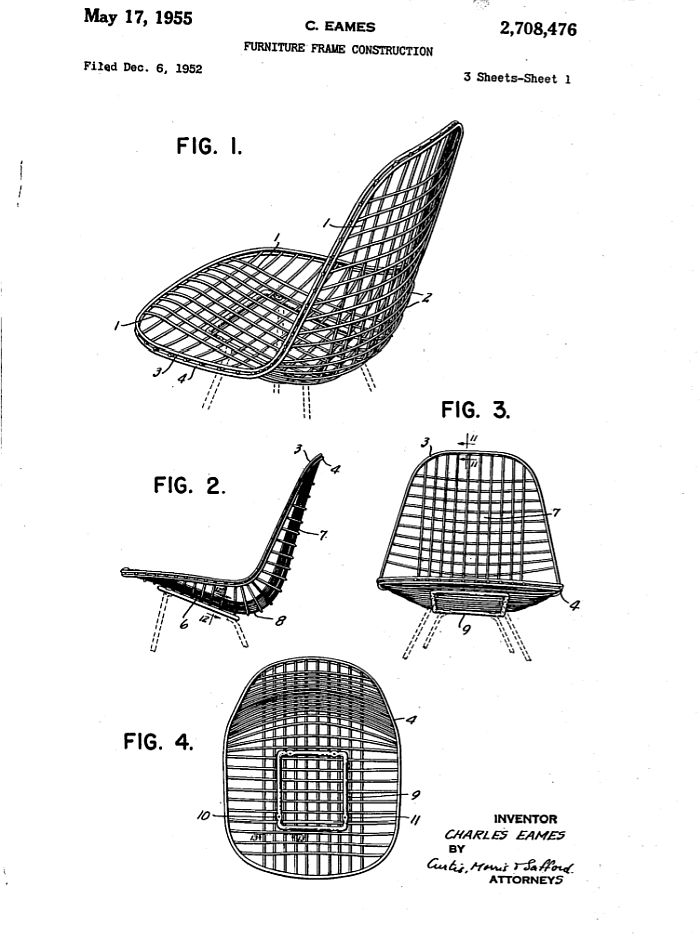

On May 17th 1955 Charles Eames*, as assignor to the Herman Miller Furniture Company, was granted US patent 2,708,476 for a "Furniture Frame Construction", specifically for, "a skeleton type metal furniture frame or shell construction" formed from "a plurality of lengths of wire arranged in crossed relation with another plurality of lengths of wire and welded thereto at their intersection..."1

A patent which although important and interesting in itself, is and was in many regards just as important and interesting for developments that arose on account of it. And for what its (hi)story can teach us about the work of Charles and Ray Eames........

The path to patent 2,708,476 begins, as with the path to most all patents, with a problem; albeit not a problem with the construction of metal furniture shells, but with the construction of fibreglass furniture shells......

......but before we get there, let us as take a couple of steps backwards......

Charles Eames and Ray Kaiser met at Cranbrook College in Art in the autumn of 1940: she, having spent several years studying art in New York, a period which saw her become one of the earliest members of the influential American Abstract Artists Group, was returning to her native California and stopped at Cranbrook College, largely, if we understand correctly, to immerse herself briefly in the atmosphere of the institution and to advance her general understandings of artistic processes, rather to study per se. He, having been brought to Cranbrook in 1938 by Eliel Saarinen as a fellow in the school’s Architecture and Public Planning programme, had been appointed Instructor of Design in 1939. And at the moment Ray Kaiser arrived in Bloomfield Hills was busy, alongside Eero Saarinen, with the development of an entry for the MoMA New York's Organic Design in Home Furnishings competition: a competition seeking works which represented "a fresh approach to what our way of living calls for in furniture, fabrics and lighting"2, and a project to which Ray Kaiser contributed, at least a little, or in her own (possibly over modest) words, "I didn't work - I was like a hand"3, a hand that also prepared the accompanying presentation drawings. Saarinen and Eames (with Kaiser's hand) were awarded first prize in the category "Seating for a living room" with a collection which in addition to the "Conversation" armchair and "Relaxation" lounge chair which later became the Vitra Organic and Organic Highback chairs respectively, also featured a sectional sofa concept that has largely vanished, and a side chair.

And a seating collection featuring shells crafted from moulded plywood. A material which, as we all learned from the V&A Museum London's exhibition Plywood: Material of the Modern World, having enjoyed a wide popularity in the mid 19th century became somewhat maligned and stigmatised in the later 19th century, but was enjoying a glorious comeback in the early 20th century, including in context of furniture, not least because its ready formability allowed for the creation of furnishings conforming to evolving contemporary understandings, requirements and realities in a resource light, industrial process. Something, in an early 20th century context, arguably first exploited by the Aaltos and Marcel Breuer, and taken up with gusto by Saarinen, Eames and Kaiser.

In 1941 Ray and Charles married and moved to Los Angeles where they continued their experimentation with moulding plywood, experimentation that was largely furniture focussed: until the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour saw America formally enter the Second World War, a turn of events which, on the one hand saw the necessary raw materials for their experimentation become ever rarer, and on the other engendered within the pair a feeling of, as Ray Eames later recalled, "an obligation of what we could do to help the situation. We began by talking to an old friend of Charles's who was in the Navy and heard about this terrible condition: the leg splints that were being used, which were metal, a scarce material. Also, the design of them was so bad that it was actually contributing to deaths rather than helping anyone"4. A sense of an obligation, a "terrible condition" and experience with moulding plywood which saw the Eames develop their famed plywood leg splints and stretchers for the US military, works which were submitted for patent on May 28th 19425; Charles as assignor to Evans Products Company of Detroit with whom the Eames had teamed up as producer, and with whom they would subsequently develop numerous plywood radio cases and also their first commercial moulded plywood furniture, including a children's collection and the LCW and DCW chairs; works which following George Nelson's 1947 appointment as Design Director at Herman Miller, transferred, with Charles and Ray, from Evans to Miller.

Much as the initial experimentations with plywood were (at least partly) stimulated by a MoMA New York competition, so the next step in the Eames career.

In 1948 the Eames Office was invited to participate in the MoMA's International Competition for Low-cost Furniture Design, the museum teaming them up with the University of California Los Angeles' Department of Engineering for the challenge of developing "furniture that is adaptable to small apartments and houses, furniture that is well-designed yet moderate in price, that is comfortable but not bulky and that can be easily moved, stored and cared for..."6 A challenge the combined Eames/UCLA team approached through chairs featuring shells crafted from stamped metal, specifically steel and aluminium, a material/process which according to the Eames is/was “the technique synonymous with mass production in this country, yet “acceptable” furniture in this material is noticeably absent…”7

One possible reason being, as they soon realised, the cost: a high cost which (a) was against the spirit of a low-cost furniture design competition, and (b) was against the Eames' principles of providing "the best to the greatest number of people for the least"8. Fortunately an alternative was appearing over the horizon: fibreglass.

First patented in the 1930s, fibreglass had found a widespread use in context of the War, largely in conjunction with the aircraft industry, and post-War was starting to make inroads into furniture design, not least in the form, pun intended, of Eero Saarinen's 1948 Womb Chair for Knoll. And in the same year in the form of an experimental fibreglass lounger Charles and Ray submitted independently of the UCLA to the Low-cost Furniture Design competition. And which today is better known as La Chaise.

Thus it came to pass that together with Gardena, California, based Zenith Plastics, Charles and Ray Eames set about translating their stamped metal armchair and side chair shells into moulded fibreglass armchair and side chair shells.

Which brings us back the late 1940s and the path to patent 2,708,476.

While the translation of the metal armchair shell to a fibreglass armchair shell proceeded, as far as we can ascertain, without greater complications, the first fibreglass armchairs being launched in January 1950, the Eames ran into problems with the side chair shell, specifically the early versions were prone to cracking at the edges, Charles Eames later recalling that period, possibly with just a hint of theatrical melodrama, as "the most desperate hours"9; "desperate hours" in which, one presumes, by way of finding a new space in which to consider the problems with the single piece fibreglass shell, the pair decided to "go to the opposite extreme and do a molded, body-conforming shell depending on many, many connections — but connections that we as an industrial society were prepared to cope with on the production level."10

A statement which, we'd argue, highlights two guiding principle's of the Eames understanding of chair design: "body-conforming shell", "we as an industrial society"

The first isn't in itself new, throughout history furniture makers have sought to form their chairs so as to aid sitting comfort; largely doing so by hand. And one chair at a time. A situation that was still very much the case in late 1940s America; George Nelson, for example, noting in the course of his tour through the contemporary American furniture industry not only a demographic largely composed of small manufacturers, but that "the most important single fact about furniture is that it is a craft product built around one material - wood - using techniques that originated centuries ago, and practically every distinguishing characteristic of the industry can be traced back to this fact."11∱

The Eames, along with the likes of, and amongst others, a Saarinen or a Nelson, sought to update that industry, sought to overcome what Nelson deliciously terms an "impressive technological lag", sought to industrialise the process of producing "body-conforming" chairs, and in many regards the Eames chair design work, certainly in the 1940s, can be considered more about developing processes for the controlled, standardised, serial, 3D forming of materials than about questions of form or function; or perhaps more accurately put, about developing industrial processes for the controlled, standardised, serial 3D forming of industrial materials. Materials such as plywood: with their entry for the Organic Design in Home Furnishings competition Charles Eames and Eero Saarinen (with Ray Kaiser's hand), arguably, achieved the first 3D moulded plywood seat shells. And thereby, arguably, the first 3D moulded seat shells. That ubiquitous staple of our contemporary furniture industry.

The development of the Eames stamped metal and moulded fibreglass shells can, must, be considered a continuation of their attempts to industrialise 3D forming in the furniture industry: stamped metal being "the technique synonymous with mass production in this country", while in context of the fibreglass shell, Charles noted, while recalling those "most desperate hours" that, "the thin molded shell really belong to the jet age. As far as furniture was concerned, we were still at the Wright Brothers level."12

Similarly the step to patent 2,708,476 was primarily a novel materials and process step, a step whose inspiration was "these fantastic things being made of wire — trays, baskets, rat traps - using a wire fabricating technique perfected over a period of many years"13: a contemporary industrial process that could help them industrially produce contemporary "body-conforming" seat shells. And not uninterestingly a material which, as with plywood, wasn't in itself new - one recalls, for example, the Viennese iron wire furniture of an August Kitschelt that developed parallel with the bentwood works of a Michael Thonet, in that first age of the industrialisation of furniture production - but was a material being rediscovered and re-imagined in and for a new industrial age.

Specifically re-imagined by Charles and Ray Eames in a 3D moulded form, in a 3D moulded body conforming side chair shell.

Much as considerations on the Eames experimentations with wire, fibreglass, stamped metal and plywood helps one better understand the important role of processes and materials in the Eames early furniture works, so does the form of the seat shell depicted in patent 2,708,476 help one better understand the secondary role formal considerations played at that period: the seat shell depicted in patent 2,708,476 is essentially the same as the fibreglass side chair shell they were having trouble with, is essentially the same as the stamped metal side chair shell, is essentially the same as the 1940 plywood side chair shell. Or put another way, one can summarise the Eames chair design work of the 1940s as attempts to recreate the same forms in differing materials, as rudimentary, elementary, attempts to harness new materials and processes for furniture production. Not that the Eames were alone in formally repeating themselves, Eero Saarinen's 1948 Womb Chair is every bit a formal development of the 1940 plywood Conversation chair as is the Eames fibreglass armrest shell: while Saarinen puffed it out a bit, the Eames reduced it and filled in the hole. Similarly Saarinen's Tulip chairs must be considered a further development of the 1940 plywood armchair and side chair forms. And thereby underscoring that oft forgotten understanding that in furniture design it's not (always) the object itself that is the most interesting aspect, it is (often) the context in which the object was developed, the ideas and understandings which drove its creation, the material and/or the processes employed in their development.

So the wire shells, it's not how the shells look that's important, but why they exist and the process of their development.

A development process that began with considerations on a repeating triangular structure but which quickly, and we'd argue fortunately, moved on to "a plurality of lengths of wire arranged in crossed relation with another plurality of lengths of wire and welded thereto at their intersection"; a construction principle which not only bequeaths the structure its stability, but also allows for its moulding, allows for "a mesh of grid-like body support with portions of the mesh distorted to form compound curved sectional contours conforming in general to body contours of a person in seated or reclining position thereon..."

Patent 2,708,476 explaining in excruciating detail just how that is achieved; and how it came to be that in January 1952 Charles and Ray Eames launched their new Upholstered Wire Chairs.

Upholstered Wire Chairs?

Upholstered Wire Chairs.

"Upholstered"? But........?

We know. We know. That today the Eames wire shell is largely understood as an unadorned object is largely a contemporary understanding, and one that tells us a lot about how we translate furniture into our contemporary world, and by extrapolation how we translate the past into our contemporary world; however, at its launch in 1952 and throughout subsequent years the wire shell was very much positioned, marketed as, an upholstered object.

Which brings us to those aforementioned important and interesting developments that arose on the path to patent 2,708,476.

On December 8th 1952, and thus just two days after submitting the "Furniture Frame Construction" application, Eames/Miller submitted a patent application for a "Base Construction for Furniture", an application granted on December 21st 1954 as patent 2,697,57514 and pertaining to an entwined metal wire base, a base known, near universally, as the Eiffel Tower, that base synonymous with not only the wire shell chair nor only the fibreglass/plastic shell chairs, but with Charles and Ray Eames. And a base, arguably, only developed because the problems with the fibreglass side chair shell saw the Eames experiment in depth and detail with metal wire.★

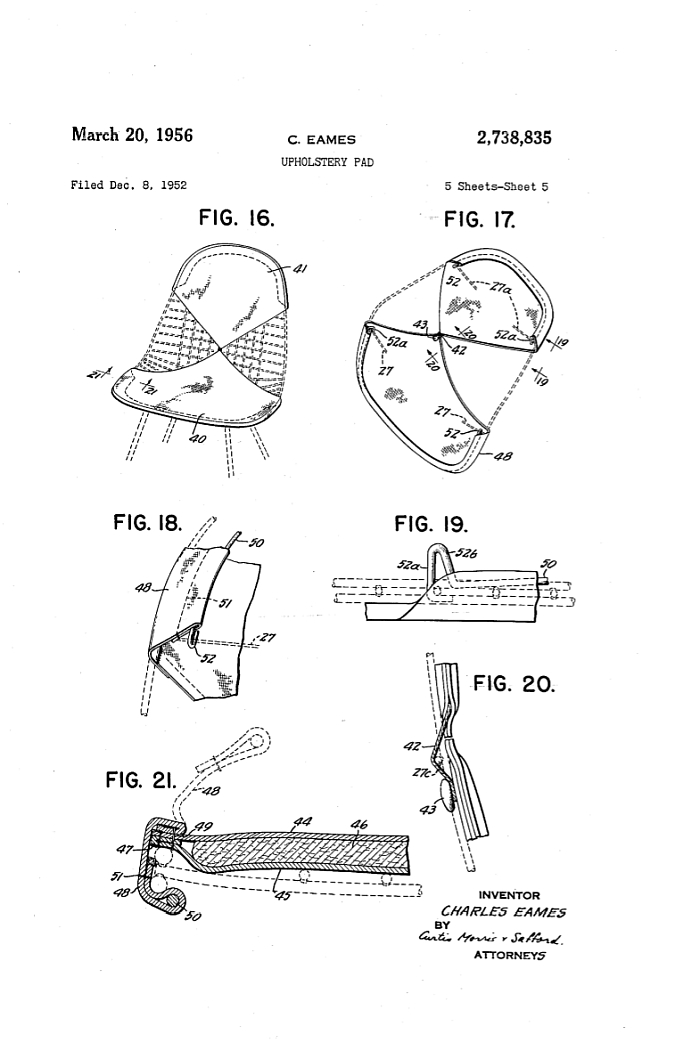

Similarly patent 2,738,835. Also applied for on December 8th 1952, and which is innocuously titled "Upholstery Pad"15.

In the 1940s, as seating became increasingly flexible, variable, responsive, light and inexpensive, upholstery and upholstering remained stubbornly inflexible, static, heavy and expensive. In their entry for the 1940 Organic Design in Home Furnishings competition the Eames and Saarinen began approaching a solution, an approach which saw them replace more traditional upholstery materials and practices with a layer of foam rubber, at that time a novel material16. And an approach continued in context of the development of the wire shells by the Eames, together with their long time collaborator, and stalwart of the early Eames Office, Don Albinson, an approach again based around a layer of foam rubber, and an approach which resulted in "an upholstery pad readily attachable to and detachable from a chair."17

A concept which for all that it sounds thoroughly normal now, was then thoroughly new: new technically, not only in terms of materials but in terms of production, upholstery becoming as it did not only mass producible but mass producible independent of the mass producible chair. And new conceptually, represented a whole new approach to upholstery, a whole new relationship with upholstery, a whole new understanding of upholstery. Understandings and relationships very much of their time and the evolving understandings of and relationships to furniture, and also very much in context of the Eames humanising of the more clinical aspects of functionalist furniture, or as Charles Eames phrased it in 1954, "the trouble with modern design is not that its too functional, but that it is not functional enough in human terms"18; the Eames kept the focus on the functionalists' standardisation, industrialisation, contemporary materials, but were happy to keep that under a leather or tweed upholstery. Ideally a low-cost leather or tweed upholstery, and as Daniel Ostroff discusses, the development of the two-piece "bikini" cover, that upholstery solution so characteristic of and synonymous with the wire shell, was about reducing the material used to the minimum required to ensure seating comfort, and thereby reducing the cost19. And at the same time, although we doubt that in the early 1950s anyone was considering such, reducing the resource usage.

Formally launched in January 1952 at the winter furniture fairs in Chicago and Grand Rapids20 the new Eames Upholstered Wire Chairs made their public debut in the same month in context of a presentation at Macy's in New York, a presentation which not only underscores the important, central, role large department stores played in the dissemination of contemporary furnishing ideas in post-War America, but a presentation which in addition to the wire side chair shells also featured a long since lost wire lounge chair21, a work of which we can find no photographs of in-situ in Macy's; but, if its the same as the experimental model wire lounge chair depicted in the Vitra Design Museum's Eames Furniture Source Book22, it would represent a further development of the 1940 plywood Relaxation chair. And to be honest we'd be surprised, and a little disappointed, if it wasn't.

From the six versions✢ in which the wire shell was originally offered only the versions with the wooden legs and the Eiffel Tower base are still produced today; and that somewhat fittingly, the DKW and DKR being as they are the two two chairs most closely associated with the path to patent 2,708,476.

Not, as we say, that the DKW and DKR should be our focus, much more they stand as conduits for what patent 2,708,476 and the path to it teaches us about Charles and Ray Eames, about furniture, about design, about materials and processes, about the relationships between materials, processes, furniture and design, about designers as being more than givers of form, and for all about the value of occasionally stepping away from a problem and re-approaching it from a different angle. Such might not solve the initial problem, but could lead you to new, unexpected, exciting, locations.

And in the interests of completion, in June 1953 the Eames fibreglass side chair shell was formally launched in Chicago23, a work which, we'll argue, without any evidence other than a gut feeling from reading 1950s newspaper clippings, initially stood somewhat behind the wire side chair shell in the Herman Miller portfolio, stood somewhat in the shadow of the wire side chair shell, or at least as much as one can stand in the shadow of a wire shell: until in 1955 when Herman Miller launched the Eames DSS, a work which for all it may lack the poetry of the DSR or DSW, is stackable and inter-linkable, attributes which, as patent 2,893,469 describes made the DSS "suitable for public seating use, such as auditoriums, schools, meeting houses and churches"24, institutes who clearly understood the benefits of such attributes and helped make the DSS the highest selling of all Eames chairs25.

1956The lack of a public presence in the 1940s shouldn't however be confused with a lack of contribution to the Eames Office, but is clearly the source of her still only partial visibility.

∱ In the interests of clarity and fairness it is important to note that Nelson's tour through the US furniture industry occurred at around the same time he was in the process of being appointed Design Director at Herman Miller, and must be understood as him achieving an overview of the industry, the market and the competition. A very cheeky, very Nelson, process given that we don't believe for a minute he informed any of the companies he visited that he wasn't just a journalist from Fortune, but the next Design Director at Herman Miller. He certainly doesn't mention Herman Miller in the text, but does praise Charles Eames and his Evans plywood furniture, those objects which were about to transfer to Herman Miller, and of which Nelson opined "should the furniture prove acceptable to the public in both design and price, Eames will have added to a brilliant contribution to furniture design a production and merchandising factor of immense importance, for the present craft basis of the industry will be further undermined." So no conflicts of interest there then! Whereby we must also add that despite the bias in the text, Nelson's assessment and gauging of the 1940s US furniture industry he found is probably very accurate, and certainly not an assessment and gauging we'd dispute, George Nelson was a very keen, critical and astute observer and analyst, but one must be aware of the potential bias in this text.

1950However one must also note that although the metal shells developed for the Low-cost Furniture Design competition were meant to be used with a variety of bases, in context of the competition there are no filigree wire bases, and thus, one presumes, the development of the "Eiffel Tower" and "LAR" base types both began at around the same time in the late 1940s, the one being completed much quicker than the other

✢ In addition to the DKR and DKW the wire shell was originally offered as the rocking RKR, the low lounger LKR, and the swivelling, pivoting PKW. The sixth version the, metal rod legged LKX, is available today as the DKX, essentially the same chair, just with a slightly higher sitting height.

⋄ A further path for another day is that which Harry Bertoia took to his 1952 wire Diamond Chair for Knoll.....

1US Patent 2,708,476, Furniture Frame Construction, 17.05.1955

2"The Museum of Modern Art announces terms of two design competitions for home furnishings", Press Release, 30.09.1940, Museum of Modern Art, New York

3Ray Eames, Oral history interview with Ray Eames, 1980 July 28-August 20, Archives of American Art, https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-ray-eames-12821#transcript, accessed 16.05.2020

4ibid

5US Patent 2,395,468, Method of Making Laminated Articles, 26.02.1946

6René d'Harnoncourt, New Design for Low-cost Furniture, in Edgar Kaufmann, Jr [ed], Prize designs for modern furniture from the International Competition for Low-Cost Furniture Design, Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1950 Available at https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/1795 accessed 16.05.2020

7Text from the Eames Office/UCLA entry for the International Competition for Low-Cost Furniture Design, reproduced in Mateo Kries, Jolanthe Kugler [eds], Eames Furniture Source Book, Vitra Design Museum, 2017

8Sympathetic Seat, Time, 10.07.1950, Vol. 56 Issue 2, p47

9Olga Gueft, 3 Chairs/3 Records of the design process 1: Charles Eames Leisure Group, Interiors, CXVII, No .9 (april 1958): 118-22, reprinted in Daniel Ostroff [ed.], An Eames Anthology: Articles, Film Scripts, Interviews, Letters, Notes, Speeches, Yale University Press, 2015, 167-170

10ibid

11George Nelson, The Furniture Industry, its geography, its anatomy, its physiognomy, its product, Fortune, Time Inc, New York, January 1947

12Olga Gueft, 3 Chairs/3 Records of the design process 1: Charles Eames Leisure Group, Interiors CXVII, No .9 (April 1958): 118-22, reprinted in Daniel Ostroff [ed.], An Eames Anthology: Articles, Film Scripts, Interviews, Letters, Notes, Speeches, Yale University Press, 2015, 167-170

13ibid

14US Patent 2,697,575 Base Construction for Furniture, 21.12.1954

15US Patent 2,738,835, Upholstery Pad, 20.03.1956

16Chair Construction, in Eliot F. Noyes [ed] Organic design in home furnishings, Museum of Modern Art, New York 1941 Available at https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/1803 accessed 16.05.2020

17US Patent 2,738,835, Upholstery Pad, 20.03.1956

18Harriet Morrison, "Civilized touch forgotten". Charles Eames deplores modern American design, New York Herald Tribune, 16.12.1954 ..... "Deplores" is harsh, but he's certainly critical. And very impressed with German pastries.

19Daniel Ostroff, The Power of a Picture? https://www.eamesoffice.com/blog/the-power-of-a-picture/ Accessed 16.05.2020

20Harriet Morrison, New wire chair that scoops in sitter is coming, New York Herald Tribune, 07.01.1952

21Harriet Morrison, Macy's shows budget-priced modern pieces, New York Herald Tribune, 18.01.1952

22cf. "Wire Armchair (Experiment) 1951" in Mateo Kries, Jolanthe Kugler [eds], Eames Furniture Source Book, Vitra Design Museum, 2017, page 199

23Harriet Morrison, Cowl design show accents modern, New York Herald Tribune, 25.06.1953

24US Patent 2,893,469 Nesting Chair, 07.07.1959

25Mateo Kries, Jolanthe Kugler [eds], Eames Furniture Source Book, Vitra Design Museum, 2017

And attributes which, arguably, mark a move by Charles and Ray Eames away from materials/processes to forms/functions. And attributes, a patent, a move, and a path, for another day⋄..........