smow Blog Design Calendar: December 15th 1888 – Happy Birthday Kaare Klint!

“Only slowly does it dawn on people that modern furniture must be designed on the basis of practical necessities”, observed the Danish architect and designer Kaare Klint in 1930.1

How Kaare Klint understood those “practical necessities”, how he understood “modern furniture”, would not only define his career, but in many regards define the development of 20th century furniture design in Denmark.

Kaare Jensen Klint was born in Frederiksberg, Copenhagen, on December 15th 1888 as the youngest of three children to Peder Vilhelm and Mathilde Caroline Klint; his mother serving, at least for a period, as a member of the board of the Copenhagen Folk High School Society, a late-19th century salon for young liberals, and is described by Thomas Bo Jensen, as a “modern women with a mind of her own”2, which we’ll take as a compliment. His father, having first studied engineering and art, established a name for himself as an architect, primarily as an architect of expressionist brick churches, and also as a critic of the traditional understandings of and approaches to architecture as taught in the late 19th/early 20th century at Copenhagen’s Royal Academy. Just one of many traits and attributes his youngest son was to inherent.

As with his father’s career, and indeed as with so many of his architecture and design contemporaries, Kaare Klint’s career began in art, the young Kaare briefly studying with the distinguished impressionist P.S. Krøyer and in 1905, aged just 16, assisting Jens Møller-Jensen with the realisation of the murals in the new Copenhagen City Hall, before, arguably under the influence of his father’s work and the circles in which his father moved, his attention, began to shift ever more towards architecture and design. For all furniture design, Arne Karlsen noting that around 1910 the young Kaare started participating, successfully so, in furniture competitions, and in 1913 was awarded a 200 Kr. second prize for what is termed “inexpensive summer furniture”, including a not uninteresting corner sofa unit proposal. And thus presumably inexpensive furniture for a summer house.3

In the same year Carl Petersen, a former pupil of Peder Vilhelm Klint, and a founding member of The Association of Free Architects, an organisation established in concurrence to the more traditional understandings of and approaches to architecture as represented and advanced by both the Royal Academy and the “official” Danish Association of Architects, invited Klint to cooperate on the furniture for the new museum building he was in the process of constructing in Faaborg on the southern coast of the island of Fyn. A cooperation from which the most popularly known result is unquestionably the eponymous Faaborg Chair; an oak framed object with a woven rattan seat and backrest, a work which owes an undeniable debt of gratitude to the ancient Greek Klismos, if with a lightness and ease rarely associated with its ancient ancestor, and a work which Klint records as being a joint Klint/Petersen cooperation. A cooperation that continued over several years and numerous further projects, including, perhaps most importantly, the redevelopment of the premises of the Copenhagen based art dealer Dansk Kunsthandel; and a cooperation which obviously made a significant impression on Kaare Klint, “apart from my father, there is probably no one I have learned more from than Calle”, he later noted.4

In May 1914 Kaare Klint married Maria Magdalena Bredsdorff, and in the same year the pair set off for Java, a trip whose exact background and purpose is currently shrouded from us, but which lasted until 1916, and during which their first son Esben, was born. And a trip that, as best we can ascertain, was of importance in the development and expansion of Kaare Klint’s understandings of architecture and design; for all the exposure to architecture and design in new contexts and cultures, including the experience of visiting the Buddhist temple at Borobudur, appears to have had a lasting effect on his understandings of and positions to the relationships between humans and both the natural and man-made environments that surround us.

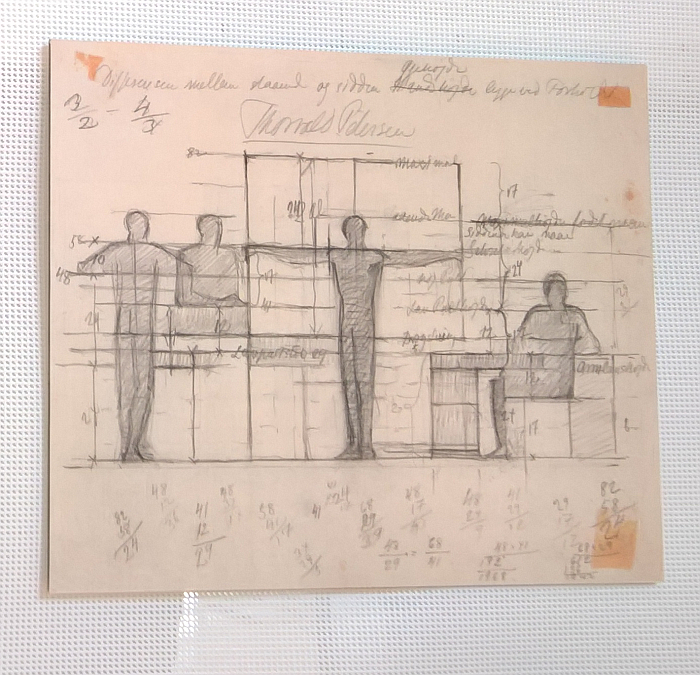

On his return from Java Kaare Klint established his own design office in Copenhagen, picked up his cooperations with Carl Petersen and began working in a, in many regards, abstract, new genre: office furniture. As best we can gauge office furniture hadn’t featured in Klint’s work pre-Java, and in how far his experiences in Java were relevant to awakening his interests are a matter of conjecture; however, one can propose a connection based on the fact that Klint’s first dealings with office furniture were on a largely theoretical basis and involved a careful and thorough measuring of the human body and its transposing onto objects of office furniture, of defining the dimensions and proportions of office furniture on the basis of human dimensions and proportions.5 A concept which in architecture goes back to antiquity, most popularly to the 1 BCE Roman architect Vitruv, but which in terms of furniture was, at that time, a relatively new concept, if one which in the course of the 1920s came to the fore in the more functionalist streams of International Modernism; Mart Stam, for example, writing in 1929 that “the dimensions of our objects should therefore be human dimensions”.6 Kaare Klint was of such an opinion a decade earlier. And a good two decades before Le Corbusier developed his Modulor system.

Whereby we, once again, find ourselves reflecting in our, for want of a better phrase, western tradition. If however we step out that particular bubble we find that in his 6th century CE Brihat Samhita the Indian astronomer and mathematician Varāhamihira presents his proposals for the proportions and dimension that should be employed in both architecture and furniture; a work popularly known throughout the Buddhist world and a focus on proportions and dimensions which first appears in Kaare Klint’s understandings post-Java. Thus allowing a supposition to be entertained that Klint’s mathematical approach to furniture design may have at least been nurtured on Java. And was possibly sown there.

In addition to, or perhaps on account of, considering the scale, proportions, dimensions and relationships of objects of office furniture, Kaare Klint also started considering the interior of office storage furniture more than the exterior; an important change of perspective as it allows, forces, one to consider the object from a functional aspect rather than a decorative aspect. With all the differentiated understandings and new possibilities such a change of perspective allows.

And a change of perspective that Kaare Klint was, arguably, one of the first to undertake.

One of Kaare Klint’s sketches of human proportions, as seen at Gesamtkunstwerke – Architecture by Arne Jacobsen and Otto Weitling in Germany at Felleshus, The Nordic Embassies, Berlin

In 1920 Kaare Klint was awarded his first solo architectural commission, the renovation of the Schæffergården mansion house in Jaegersborg to the north of Copenhagen, and shortly afterwards commenced that architectural project for which he is, arguably, most closely associated: the conversion of Copenhagen’s Frederiks Hospital into the Danish Museum of Art & Design, the contemporary Designmuseum Danmark. And two architectural commissions which were to have an important influence on his furniture design work, not only in context of deepening his understandings of both proportionality and the connection between objects and humans, those aspects he had began exploring in context of office furniture, but also tended to confirm his understandings of standardisation, understandings not unrelated to his considerations on proportions and dimensions, and an understanding he, arguably, found confirmed in his studies of Nicolai Eigtved’s original 1750s plans for Frederiks Hospital and the realisation that in the development of the wards Eigtved had used a repeating quadratic form defined by the space required for a bed, associated equipment and personnel.

And which all led him to to the opinion that one could, should, must “lay down firm norms for ordinary buildings”, albeit these should be “linked to life, to utility, and not to abstractions in which the “golden section” and other hazy concepts are “the philosopher’s stone””.7 And thus a demand for a move away from traditional artistic understandings of the development of forms, and a move towards the application of a more human centred understanding and approach. If one so will, a demand for rationalisation in interests of utilisation.

And a standardisation, firm norms linked to life, to utility, as the basis of design that caused Kaare Klint to reflect on office furniture in context of…… paper formats. Or as he opined in 1930, “if you want to try to solve the task of furniture dimensions, then there is no escaping paper standardisation.”8 For, and to paraphrase Klint, what are desks, filing cabinets, secretaries and bookcases, if not functional storage spaces for paper of varying sizes? And so what should be the basis for their design, certainly if that design is to be linked to utility and human use? Thoughts that for all they may be commonplace today, weren’t common, or popular, at that time in Denmark.

But what should be the basis for those standardised paper formats? A question that in 1930 was highly topical. And which offers a nice insight into an aspect Kaare Klint’s thinking and understandings.

In 1922 Germany had introduced a new metric system of paper standardisation which in the course of the 1920s had been, when at first slowly, adopted by other nations and was moving, slowly, towards becoming the standard; and of which Kaare Klint was sceptical, as he was of much originating in 1920s Germany, and questioning if the new system with its abstract basis of calculation and its A1s, A2s, A3s, A4s, A5s, etc, would or could produce anything meaningful, and defending the existing folio, quarto, octavo et al, as formats linked to the reality of life, the realities of use, the human species, and formats which had proven their worth over time. Kaare Klint similarly preferring to work in inches, feet, cubits, etc as units linked to life and which had “stood the test of time” before having “to give way to such a sad abstraction” that is, for Klint, the metre.9

And a standardisation, firm norms linked to life, to utility, as the basis of design that served as a central thread of Kaare Klint’s teaching, that component of his biography for which he is, arguably, best known.

And which inarguably is amongst the more important components of the Kaare Klint biography.

Kaare Klint’s teaching career began in 1919 when he took up a position at Copenhagen Technical College, and where in 1920 he established a course in furniture draughting and construction; a course aimed, primarily, at carpenters seeking to expand their skills and knowledge in order become Master Carpenters, and which, as Anne-Louise Sommer very neatly describes, served as the foundation of the teaching programme for his more famous tenure as a Professor at the Royal Academy.10

Yes, that Royal Academy which Peder Vilhelm Klint and his associates had so roundly criticised at the turn of the century. However as the century turned so a new wind blew through the corridors and ateliers of the Academy; a new wind which in the course of the late 1910s and early 1920s blew away many of the more traditional elements and saw the awarding of Professorships to the likes of Carl Petersen, yes that Calle, and also Ivar Bentsen, who had not only cooperated with Kaare Klint on the conversion of Frederiks Hospital to the Danish Museum of Art & Design, but was married to Kaare Klint’s sister, Helle. And thus as Arne Karlsen, somewhat understatedly phrases it, “towards the mid-1920s it was consequently architects who were close to Kaare Klint professionally and as individuals who set the tone at the Academy”.11 And thereby easing the path to Klint’s appointment in 1924 as a tutor and subsequently in 1925 as Associate Professor with responsibility for the newly created Department of Furniture Design.

A department whose alumni under Klint’s professorship include the likes of, and amongst many, many, others, Arne Jacobsen, Ole Wanscher, Mogens Koch, Orla Mølgaard-Nielsen and Børge Mogensen.

And thus imbuing Kaare Klint’s Department of Furniture Design a near mythical place in the (hi)story of furniture design in Denmark.

If a mythology which, as with most all mythologies, has a much more prosaic and practical reality.

In October 1930 the Danish journal Arkitekten published an article by Kaare Klint under the title, Undervisningen i Møbeltegning ved Kunstakademiet, The teaching of furniture draughting at the Academy of the Arts, and in which Kaare Klint expounds on not only the teaching of furniture draughting at the Academy of the Arts, but, and if in a very brief and digested form, his entire ethos and understandings of furniture design.12

Limitations of time and space preclude at this juncture a detailed analysis of the text, we’ll save that for another day, and restrict ourselves here to the observation that it opens with the information that the course of studies began “with a sketch and study of an older or newer piece of furniture, the main form of which can be used to this day”, and specifically, “furniture whose design corresponds to the intention, and whose use has not undergone any significant change over time. One can mention chairs, the many different types of tables, bookcases, the most common drawer furniture, etc.”13

A sketch and study which was not intended, as had been the case with sketching exercises in furniture design education in the preceding decades decades, to enable the student to copy the object in question: but to enable them to understand it. And having understood it to develop something new, something contemporary, from it.

An understanding of the existing as the best model for the contemporary which was every bit as central to Kaare Klint’s understandings of furniture as human scales, proportionality and standardisation, and an understanding that he in all probability inherited from his father who once opined that “”unique pieces” are good, but the patterns and forms that can stand being repeated and varied are better”14, and who also demanded, “let us cultivate the object, the surface, the materials in accordance with its essence and the requirements of the times; let us never indulge in copying old styles, but through a thorough education and a study of old ages’ unfailing taste and dignified approach to style, cultivate our personal style, with the idea of creating cozy, beautiful, and grandiose surroundings for the life and activities of contemporary man”.15

Or as Kaare Klint phrased in 1930, with one eye very much on Bauhaus and their ilk, “in an aversion to everything old one loses sight of and excludes the best available help, namely to build on the experiences that have been garnered over the centuries. The problems are not so new, they have in many cases been solved before.”16

Kaare Klint’s understandings of what should and could arise from such an education and a study, how the experiences of the past could and should be best employed, were arguably more functional, rational, sober and certainly less “grandiose” than his fathers, but the principle was essentially the same. And a principle that Klint embodied in his so-called Rød Stol, Red Chair, developed in 1927 for the new Danish Museum of Art & Design and which is as much a manifesto as a piece of furniture, combining as it does the seat and base of an 18th century Chippendale chair, a work of which Klint notes the “seat height, width, depth are as they should be” and that “the base is excellently constructed and shaped, quite similar to the demands we make today”, but whose backrest “is higher than necessary”, and consequently was swapped for the backrest from another 18th century chair which Klint opines is “as simple in design as the base was in the first”.17 A mash up of two existing chairs that produced the object he required for the museum’s lecture hall.

And before anyone starts pointing accusative fingers, one must never forget that Thomas Chippendale’s furniture designs were intended to be reproduced and adapted, The Gentleman and Cabinet Maker’s Director was in many regards Open Design v0.5, and thus Klint’s utilisation of Chippendale for his Rød Stol is a deliciously logical and satisfying step. And Klint himself would continually rework the Rød Stol, creating numerous versions for differing projects; and also regularly reworking the Faaborg Chair, a work that, as already noted, owed a notable debt of gratitude to the ancient Greeks.

And also restrict ourselves here to the observation that in contrast to chairs et al, “significant changes in use can only be found in a few furniture groups, e.g. office furniture, wardrobes, buffets and beds”. And in context of his teaching at the Royal Academy, Klint transferred his considerations of office furniture onto wardrobes, buffets and beds, moved from the office environment to the domestic, including moving from the standardisation of paper as the basis for design to standardisation of cutlery and crockery: Klint and his students measuring all manner of tableware objects from innumerable sources, discovering thereby that the variation in sizes within genres were minimal, that standards could be defined, and subsequently developing buffet designs that allowed for an optimal and practical storage of the requisite dinner service, glasses, cutlery et al. And that despite what he clearly understood as little demand for such amongst his fellow Danes, that while the practicality of a chair was generally understood amongst Danes, “whether a buffet is practical, whether it provides ease and joy through its simple usability, they are quite indifferent, as long as it looks nice, the longer the sideboard the better, if you have room for it. However, it is my conviction that in time one will make the same demands on furniture as on a modern house.”18

And also also restrict ourselves here to the observation that, “on the basis of these dry facts one can learn to build a piece of furniture, anyone can then give it the changing artistic design that suits him and the time.”19

Which is exactly what his students did. Not least because Kaare Klint never taught a particular style, never advocated a particular formal expression or character, rather taught the basics of functional, rational, practical, humane, furniture design, taught a methodology for designing furniture that is suitable and appropriate for its task. And left his students to find, to develop, their own understandings of the artistic.

And an Arne Jacobsen isn’t an Ole Wanscher who isn’t a Mogens Koch who isn’t an Orla Mølgaard-Nielsen who isn’t a Børge Mogensen who isn’t an Arne Jacobsen.

Yet all are definitive of 20th century Danish furniture design.

For all 1950s and 1960s Danish furniture design, that near mythical place.

Chairs for the Bethlehem Church Copenhagen by Kaare Klint, 1936 (photo Hans Andersen via commons.wikimedia.org CC BY-SA 3.0)

In December 1930 Peder Vilhelm Klint died and Kaare Klint both took over the construction of the Grundtvig’s Church in Copenhagen, a work his father had started to construct in 1921, and which counts, inarguably, as Peder Vilhelm Klint’s most popularly known, and most important, work; and also completed the design, and oversaw the construction, of the Bethlehem Church, also in Copenhagen, and for which Kaare Klint designed chairs for the congregation rather than installing pews, a novum in Denmark. And chairs which again reflect Kaare Klint’s position of adapting the existing rather than inventing the new: realised as simple ladder back chairs with rush seats the Bethlehem Church chairs are modelled on southern Italian rush seated, stick-backed, church chairs his father had ordered for Grundtvig’s church, Kaare Klint redefining materials, construction, form, and adding a small box for holding a bible, psalm book, bag, etc, And a chair which, according to Fritz Hansen, is and was the work with the longest production history within the company, being continually produced, in various versions, between 1936 and 200420

The 1930’s also seeing the development of Kaare Klint’s most commercially successful, certainly most popularly known, furniture design, the so-called Safari Chair. A work the, then, manufacturer Rud. Rasmussen described as “verdens måske første samle-selv møbel“, “perhaps the world’s first self-assemble furniture object”21, an object inspired by American photographer Martin Johnson’s book Safari – A saga of the African blue, and its images of home life in tents, and arguably also by such images in conjunction with Klint’s memories of Java; an object which aside from its flat-pack delivery, collapsibility, ready stow-ability and easy transportability, whether in the African savannah or contemporary Copenhagen, is for us always particularly notable for its moving backrest, the way the chair naturally responds to your posture and any changes therein. And a work that only became Klint’s most commercially successful, certainly most popularly known, furniture design when he was persuaded to move away from the expensive leather, mahogany and teak of the original and permitted production in more affordable canvas and ash. Klint’s understanding of tradition in units of measurement be echoed in his understanding of materials; his fixation on mahogany being every bit as strong, fundamental?, as that to the inch.

In addition to his work as an architect and furniture designer Kaare Klint was also active as a graphic designer, for all in context of De forenede Automobilfabriker, a Danish automotive concern who both manufactured their own vehicles under the name Triangle and also imported foreign brands including Fiat and Austin, and for whom Kaare’s brother Tage served as a director from 1918-1935.22 And also as a lighting designer in context of the company Le Klint, a company established by Tage Klint in 1943, initially to produce a pleated paper lampshade Peder Vilhelm Klint had designed in ca. 1900, but which quickly began producing a wide collection of lampshades by other designers, including Kaare Klint’s 1946 LK 306 which through a piece of monstrous simplicity can be used as a wall or table lamp, and the 1944 LK 101 pendant lamp, a work popularly known as the Frugtlygten, the fruit lantern. Because that is what resembles.

And works which were Kaare Klint’s last published designs. The post-War biography of Kaare Klint is at best sketchy; however (hi)story has reliably recorded that in 1945, after 20 years as an Associate Professor he was appointed a full Professor at the Royal Academy, and that on March 28th 1954 Kaare Klint died in Copenhagen, aged just 65.

There are a great many paths to approaching a better understanding of Kaare Klint.

One could, for example, consider Kaare Klint in context of his more Art Nouveau inclined predecessors, as a continuation of the likes of Thorvald Bindesbøll, Georg Jensen or Peder Vilhelm Klint; one could consider Kaare Klint in context of his contemporaries, in a Danish context for all Poul Henningsen, in an international context for all Bauhaus Weimar and Bauhaus Dessau; one could consider Kaare Klint in context of his students, of his students as a continuation of Kaare Klint. And we’d thoroughly recommend all and any paths to a better understanding of Kaare Klint.23

Not least because for all his importance to the development of furniture design in Denmark, and by extrapolation further afield, Kaare Klint is today all to easily reduced to a man of craft production, tropical hardwoods, historical types, and pre-metric measurements.

And while he was all those things, he was so much more.

As an early adopter, or perhaps more accurately, as an early 20th century re-adopter of human scales, methodic study, standardisation and a thereby achieved rationalisation in design, Kaare Klint was very much at the front of the curve in developing understandings in the 1910s and 1920s, of that move away from value through the overly ornate and decorative to value through use and utility, and thus Kaare Klint was very much one of the spearheads of Modernist design thinking in inter-War Denmark.

And although Kaare Klint’s Modernism is often understood as being, if one will, a slower Modernism than that expressed elsewhere. Was it?

Or just less brash.

For as we’ll never tire of noting, for all the popular fascination today with steel tube furniture, ’twas but a minor aspect of International Modernism, a minority interest, if no less important, relevant and critical for the development of furniture design for that fact. And throughout the inter-War years a great many designers produced interesting, important, relevant and critical furniture works in wood. Even in Germany. The glint of steel tube however all to often collectively blinding us.

And as furniture the inter-War steel tube furniture is very much a repetition of existing styles: the steel tube desks of a Marcel Breuer, for example, maintain the silhouette of traditional desks just with a lot less material, less density; while for all their revolution steel tube cantilever chairs are just quadratic chairs, one of those objects “whose design corresponds to the intention, and whose use has not undergone any significant change over time.” And thus a use of historic models very much in keeping with the Klint school of design.

And while Kaare Klint himself would never have considered working in steel tubing, and was as sceptical of Germanic steel tube furniture as he was of Germanic metric paper formats, he also opined that, “these new movements are of great benefit to the world: it is no longer fashionable to surround oneself with antiques. An interest in modern furniture art has emerged and it must be greeted with joy.”24

For what Kaare Klint wasn’t, was dogmatic. Opinionated, unquestionably; sure of the correctness of his opinion, surely; stubborn, we imagine so. But not dogmatic. Was very much in favour of each and everyone developing that “changing artistic design that suits him and the time.”

And he understood that times change; but for a Kaare Klint responding to those changing times didn’t mean jettisoning the past, but rather looking to the past, contemporary problems being not so new and “have in many cases been solved before”. One simply had to understand how to adapt the past, apply the “experiences that have been garnered over the centuries”, to contemporary realities.

And he understood that aesthetic tastes varied; but a Kaare Klint was less interested in how furniture looked, and much more in that it functioned, that it was practical for normal human use and normal human needs, that it was responsive to and off the human condition. Which isn’t to say he didn’t care about the aesthetics, but is to say that he didn’t prioritise them.

Yet today Kaare Klint is today all to easily reduced to a man of craft production, tropical hardwoods, historical types, and pre-metric measurements.

Which isn’t just to misunderstand Kaare Klint, but to misunderstand what Kaare Klint can continue to teach us about furniture, furniture design, the essentials in our relationships with furniture and the necessities of keeping our furniture modern.

Happy Birthday Kaare Klint!!

1.Kaare Klint, Undervisningen i Møbeltegning ved Kunstakademiet, Arkitekten månedshæfte, October 1930, page 201

2. Thomas Bo Jensen, P. V. Jensen-Klint: the headstrong master builder, Routledge, London, 2009, page18-19

3. Arne Karlsen, Danish furniture design in the 20th century [English translation by Martha Gaber Abrahamsen], Ejlers, Copenhagen 2007, page 34

4. unreferenced quote in Anne-Louise Sommer, Kaare Klint, Aschehoug, Copenhagen, 2007, page 36. Against our natural inclination and preference much of this post is based on secondary sources rather than primary. The primary sources being simply inaccessible under the current realities.

5. The original sketches, and a great many more Kaare Klint sketches and draughts can be found in the Danmarks Kunstbibliotek online archive, http://kunstbib.dk/samlinger/arkitekturtegninger/kaare klint Accessed 15.12.2020

6. Mart Stam, Das Mass. Das richtige Mass. Das minimum-mass. Unsere Hausgeräte und Möbel, Das neue Frankfurt: internationale Monatsschrift für die Probleme kultureller Neugestaltung, Nr 3, 1929, page 30

7. unreferenced quote in Arne Karlsen, Danish furniture design in the 20th century [English translation by Martha Gaber Abrahamsen], Ejlers, Copenhagen 2007, page 27

8. Kaare Klint, Undervisningen i Møbeltegning ved Kunstakademiet, Arkitekten månedshæfte, October 1930, page 196

10. see Anne-Louise Sommer, Kaare Klint, Aschehoug, Copenhagen, 2007, page 53

11. Arne Karlsen, Danish furniture design in the 20th century [English translation by Martha Gaber Abrahamsen], Ejlers, Copenhagen 2007, page 55

12. Kaare Klint, Undervisningen i Møbeltegning ved Kunstakademiet, Arkitekten månedshæfte, October 1930, 193-224

14. Original in, Mirjam Gelfer-Jørgensen [ed.] Herculanum paa Sjaelland, Copenhagen 1988, quoted in Thomas Bo Jensen, P. V. Jensen-Klint: the headstrong master builder, Routledge, London, 2009,page 426

15. Speach at the founding of the Society of Decorative Art, 1901, quoted in Arne Karlsen, Danish furniture design in the 20th century [English translation by Martha Gaber Abrahamsen], Ejlers, Copenhagen 2007, page 14

16. Kaare Klint, Undervisningen i Møbeltegning ved Kunstakademiet, Arkitekten månedshæfte, October 1930, page 203

20. https://fritzhansen.com/en/about-us/the-archive Accessed 15.12.2020

21. quoted in Anne-Louise Sommer, Kaare Klint, Aschehoug, Copenhagen, 2007, page 25

22. see Anne-Louise Sommer, Kaare Klint, Aschehoug, Copenhagen, 2007, page 72-73

23. With the observation that one of the major problems with approaching an understanding of Kaare Klint is not only that he himself wrote only very little, but that most of that which he did write is unpublished, can only be read, offline, in Copenhagen’s Kunstbibliotek, and for all can only be read offline in Danish: which as we’ll never tire of noting is not the most accessible of languages. As with our continual demands on the need to translate more of Poul Henningsen’s texts from their lone Danish, so if any culturally interested bilingual Danish speaker is looking for a new project, the texts of Kaare Klint would be an excellent option.

24. Kaare Klint, Undervisningen i Møbeltegning ved Kunstakademiet, Arkitekten månedshæfte, October 1930, page 203

Tagged with: Carl Hansen & Søn, copenhagen, Denmark, Design Calendar, fritz hansen, Kaare Klint, Le Klint, safari chair